That was 2024. There’s been good news. There’s been bad news.

Good news – inflation’s back in its 1% to 3% target box.

Bad news - the Reserve Bank (RBNZ) handcuffed the economy to get it there.

Whether 2024 therefore qualifies as a ‘good year’& very much depends on individual circumstances.

In a preview written late last year, I styled 2024 as The Year of Finding Out.

The theory was we would learn whether inflation was under control. We would quantify collateral damage to the economy and the unemployment rate. And we have.

So, if finding out is ‘good’, this has been a ‘good’ year. But others might have different words.

Where did we come from, and where have we ended up in 2024?

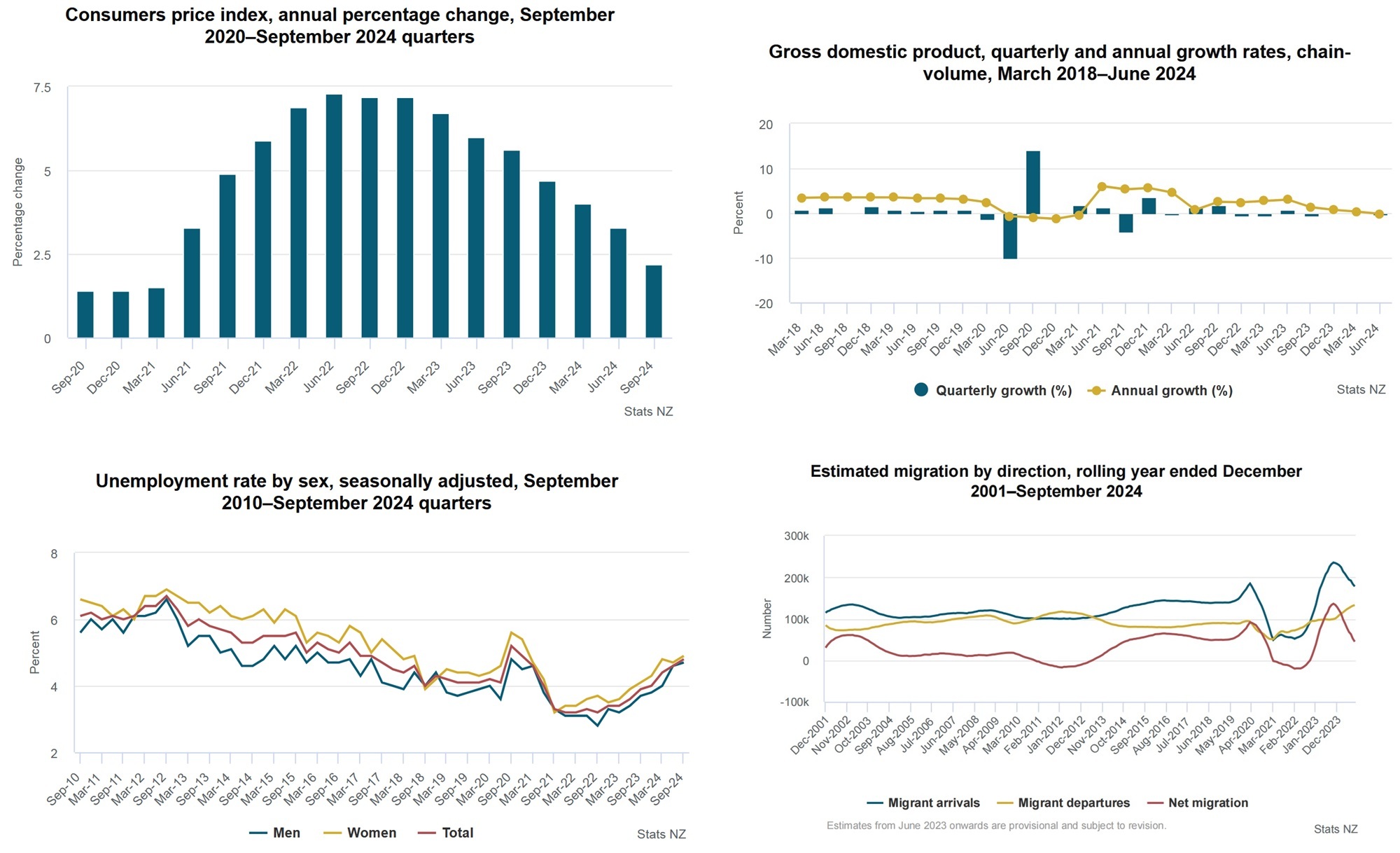

When I was writing my 2024 preview, annual inflation (as at September quarter 2023) was 5.6% - not so far from the 7.3% peak in mid-2022.

By the end of 2023 annual inflation was 4.7%. Much needed to happen for a return to the 1% to 3% targeted range this year.

Well, we made it. Down to 2.2% as of September 2024 and, only just above the 2.0% level the RBNZ explicitly targets.

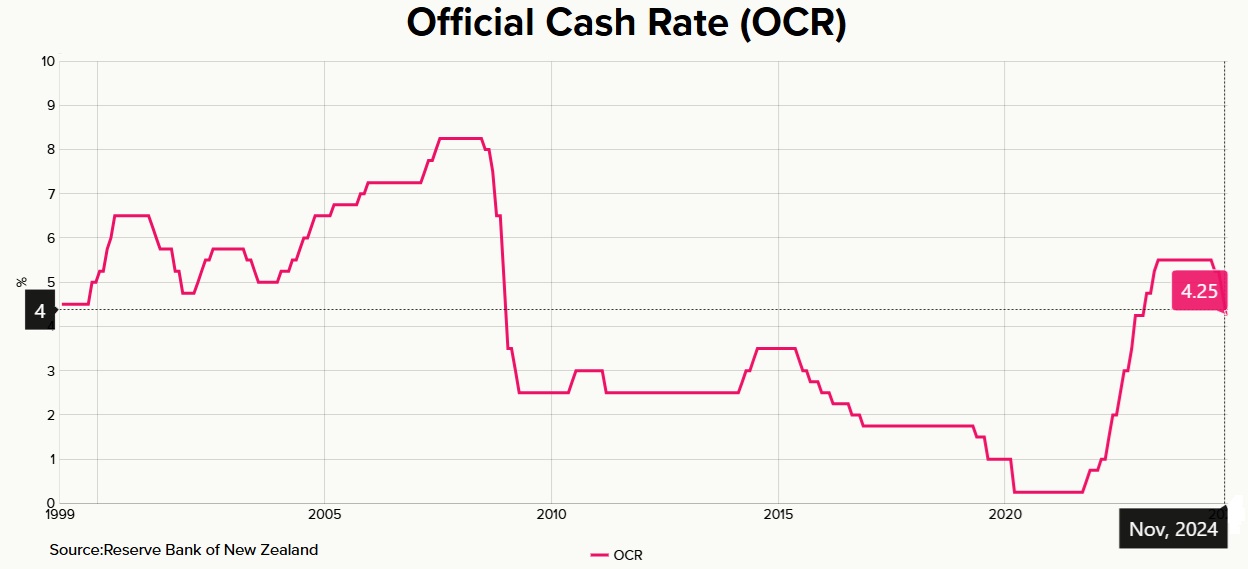

In August the RBNZ started cutting the Official Cash Rate (OCR), ending the most rapid-ever monetary policy tightening cycle, which saw the OCR& hiked from 0.25% in October 2021 to 5.50%.

The OCR will end 2024 at 4.25%. It means lower interest rate bills ahead for the roughly one-third of Kiwis (RBNZ estimate) with mortgages.

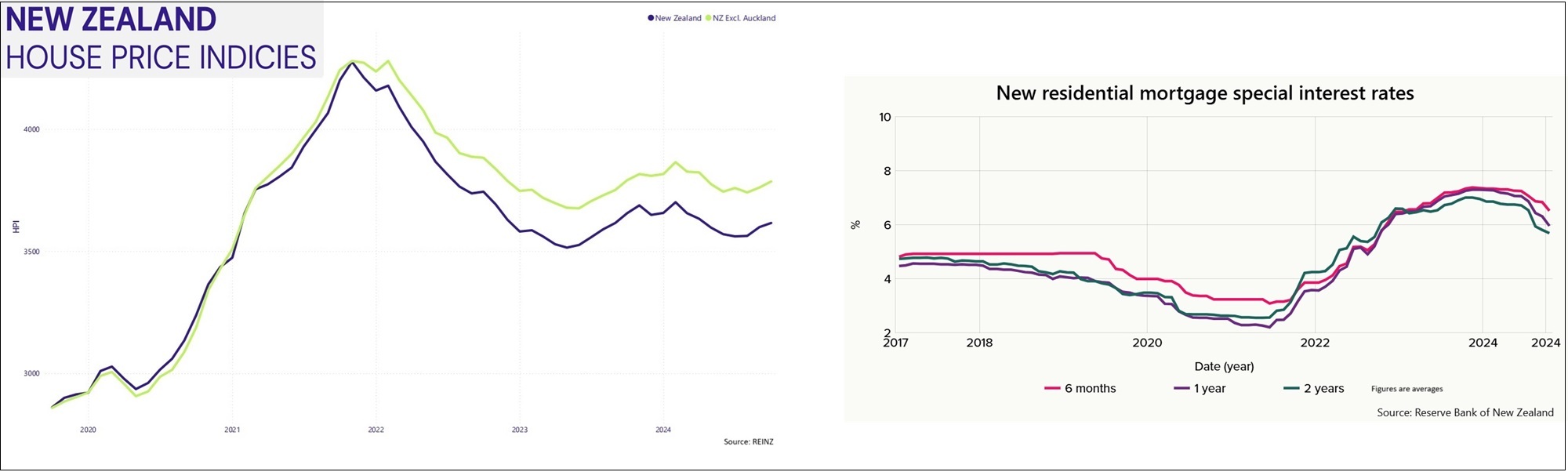

Popular one-year fixed rate mortgages (special rate) are for example already about 150 basis points lower than at the start of the year.

With most customers on fixed rates, it takes time for reductions to work through.

In its OCR announcement on November 27 the RBNZ said the average rate on outstanding mortgages had peaked at 6.4% and is expected to decline to 5.8% in the next 12 months.

So, the impact of falling interest rates is going to be a 2025 story.

There’s two sides to the interest rate coin, however. On the flip side, deposit rates are also coming down, with the six-month rate, for example about 75 bps lower since the start of the year.

Cheers and jeers

So, those who pay interest are cheering. Those who receive interest, not so much. And we should not under estimate what the impact could be of lower returns of deposit rates in the coming year.

But back on mortgages - I’ve been surprised by how well so many people have seemed to cope with what were very substantial rises in monthly interest costs. RBNZ figures show around $2 billion worth of mortgages are non-performing, which is 0.6% of the outstanding mortgage stock and around half the distressed mortgage levels seen after the Global Financial Crisis.

It is a truism though that mortgage payments will come first and other spending will be sacrificed. And that in a nutshell is the intention of OCR hikes.

So, spending dried up – and very noticeably so in the middle of the year. Hence, we see struggling businesses, closing businesses and an economy that went cold.

We don’t get very timely official GDP figures. We won’t even see the September quarter results till December 19. The figures up to June this year were grim, however. In the March quarter our economy eked out 0.2% of growth, but then in June we saw a 0.2% contraction. It meant that four out of the last seven quarters had produced negative figures (and there was a 0.0% and a +0.1% in those too). It is widely expected the September quarter GDP will also be negative. The RBNZ picks -0.2%, but expects 0.3% growth for the December quarter.

The per capita GDP figures as reported have been even more grim. Our economy has languished even as we added large numbers of migrants to our population. More hands have produced less. Up to June 2024 per capita GDP had fallen for seven consecutive quarters. The combined 4.6% drop in per capita GDP over that time has been worse than the collective 4.2% fall in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis.

(An important caveat: Stats NZ has undertaken big revisions. These will see higher GDP figures retrospectively for 2023 and 2024. The final details of this won’t be seen till the September quarter GDP figures are released, but the expectation is the revisions will make the historic GDP figures ‘less bad’ rather than particularly good.)

Employing good fortune

We are fortunate we went into the economic downturn with very low unemployment, which bottomed out at 3.2% in the September 2022 quarter. By the end of 2023 it had risen to 4.0%. And by September 2024 it stood at 4.8%, with more rises seemingly to come in the immediate future. On a seasonally-adjusted basis the unemployment level stood at 148,000 as of September - an increase of 25,000 since the start of the year.

I mentioned migration. According to Statistics NZ’s rolling 12-month figures our net gain of migrants peaked at 136,269 (235,525 in and 99,256 out) in October last year.

By September of this year (latest figures available), the 12-month running net migration figure was down to 44,907 (177,937 in and 133,030 out).

Despite rising unemployment and the flagging economy, monthly arrivals are still exceeding pre-pandemic figures. And so are the departures. Stats NZ says the long-term average for September years (2002 to 2019) before Covid was 120,200 arrivals, 91,800 departures, and a net migration gain of 28,400.

The house market looked as though it may be starting to warm up again around election time last year, but that fizzled early this year. The Real Estate Institute of New Zealand’s House Price Index for New Zealand (which takes into account changes in the composition of sales) did rise 0.5% in October, but was down 1.1% for the year. Auckland was down 3% in the year, while NZ excluding Auckland was down 0.1%.

So, that has been 2024.

It makes pretty grim reading, doesn’t it?

We can take satisfaction that inflation is back to manageable levels. That’s the big plus from the year.

But, whew, there have been a few minuses.

For me this downturn has felt very uneven in its impact – and that’s probably due to the fact that unlike a ‘normal’ recession, this one has been specifically engineered by the RBNZ and those OCR hikes.

As we get to the end of the year, we are seeing a rising tide of optimism among businesses about the prospects ahead. It does seem to me though that this is at least partly fuelled by a ‘it can’t get worse’ state of thinking, coupled with the fact that interest rate falls have come much earlier than we were led to expect. The RBNZ was suggesting rates wouldn’t come down till NEXT year - pretty much right up until it did start to cut them.

Anyway, we got through the year. And inflation’s back in its box.

What next?

I’m not big on predictions. I will, however, attempt to highlight what I see as the big issues and themes to look out for in 2025. That will be in another article coming out in a few days. Watch for that.

People will certainly be hoping for a ‘better’ year next year. But there are a lot of obstacles in front of us.

*This article was first published in our email for paying subscribers first thing Thursday morning. See here for more details and how to subscribe.

123 Comments

My concerns for 2025:

1. Inflation will continue falling towards the lower bound, creating a different set of problems.

2. Unemployment will continue to slowly rise as the consumer doesn't respond to stimulus efforts as expected.

Our problems cannot be solved until our NAct rulers admit there is a problem,

they are too busy blaming Labour to see this needs more then Austerity to fix.

They are opening the door to a Labour rebound, but their cut and balance will not fix the lack of productivity or

collapsing housing sector. Minimum wages are so high, as is electricity, that very few lower end processing can be done onshore anymore.

Cause and effect....why are minimum wages so high? why is the housing (construction) sector collapsing ? why is productivity so poor?

Exactly. This downturn looks more structural but is being misread as cyclical by economists and politicians.

Jamming more adrenaline into the economy in the form of lower interest rates may not work as well as it did in the early-to-mid 2010s.

Unfortunately it is likely to (eventually) lead to even greater asset values which will only intensify the problems.

Exactly. This downturn looks more structural but is being misread as cyclical by economists and politicians.

It's hard when there's an upheaval to not use that as an inflection point. Then what can be a shorter term movement can be read as some sort of culmination of a range of forces, rather than an instance on a line.

What's happening on a global macro level is likely going to be of a more material impact than our domestic economic affairs over this 5-10 year period.

The column is certainly not happy reading but nonetheless to me the best commentary I have read in quite a long while. Much appreciated.

Many people in the consulting world aren’t receiving bonuses this year. It may be a small % of the population, but I suspect its impact may be more significant than thought, as it is mid-high income earners

Progressive relief to those paying off mortgages but that advantage may well be needed by many to repay debt incurred elsewhere rather than embarking on spending that would assist economy recovery. At the same time lessening term deposit returns will dampen that avenue. For decades RBNZ governors and Finance Ministers have quite rightly decried the poor savings record of NZr’s across the board. Yet the sixth Labour government, coupled to the RBNZ decided on a policy to encourage NZr’s to borrow to spend to save the economy. This was catalysed by the unexpected crisis of the pandemic but the crash dive of the OCR was an ill considered knee jerk, supposedly to protect the housing market. Instead it galvanised a stampede into property investment and a resultant sky high lift in prices. What is overlooked is that the lowering of the OCR up until that point had done its dash. Those that required finance for purposeful and sound investment, had already obtained it.

For a lot of these people, a bonus is keeping their job for 2025.

My sales are below budget, but we will survive.

What the hell is it about kiwi culture that makes us prone to these spells of self-flaggelation? It's like things go wrong and we think the answer is starving ourselves for a year so that we 'come out other side stronger'. Rogernomics, the mother of all budgets, and, now, whatever we end up calling this post-covid calamity.

What this (good) article misses is how our story over the last couple of year compares to the rest of the world. Dozens of advanced economies like NZ had inflation at the same track or higher. How could they not? Look at the changes in the key global prices impacting NZ (and be grateful we weren't reliant on imported gas as well).

We stood back and let those price shocks propogate through our economy moving from fuel and oil-related products to goods more widely, then wages / services, and into rents. A bit of profiteering on the way was the cherry on the cake (we did have cash to splash after lockdowns).

I still don't think we could have done much about this propogation - we would have slowed it down with subsidies, bufferstocks and price controls, but ultimately global prices were adjusting by 20%+ and we were along for the ride.

Now, the medicine. The medieval monetarism. The machismo. The moment every central banker hopes for - their chance to do a Volcker.

RBNZ, and later Robertson and Willis, crushed the economy with higher rates and fiscal tightening. Our private debt is a relatively high 150% of GDP, so putting average borrowing costs up to over 7% meant more than 10% of our GDP was soon moving from spenders to savers (and bank equity holders). This combination of high interest rates and high private debt levels meant that our rate hiking was the most aggressive in the OECD. The media compare the interest rates but it is the combination of rates and private debt level that matters!

Important to note that at the peak (Aug 24) interest on business loans was $1.3bn per month and interest on mortgages was $1.9bn per month. I am still certain that any downward pressure on CPI from lower demand would have been cancelled out by businesses passing those extra debt-servicing costs through to prices. Remember total household consumption in NZ is about $16bn per month. So, business interest costs were 10% of household consumption - who was paying the bill? Note, that business interest costs were still $1.2bn a month in October.

Now, the metrics that matter. The most aggressive response of any advanced economy predictably crushed our economy hard, yet inflation elsewhere tracked down the same as ours as global price shocks subsided and the world adjusted to a new price level.

Sadly, we have seen the biggest increase in unemployment relative to 2019 than any country OECD country other than Hungary and Estonia. Most OECD countries have lower unemployment now than they did in 2019. Tens of thousands of kiwis have voted with their feet as opportunities evaporated. Our economy has contracted and we have lost a significant amount of productive capacity that will take years to restore. Our youth unemployment has rocketed up by around 30% and the number of people reliant reliant on a benefit has hit 13% (nearly 1 in 7). Annual increaes are still running at 10%. Jobs are still disappearing and the descent has momentum. We are creating the economic conditions for significant social issues downstream - while the Govt talk up the importance of social investment. It's ridiculous.

Friends, we have properly messed this up. The RBNZ, Govt and the commentariat owe kiwis an apology. The Govt owes kiwis a plan. But, instead, they get mini-Ruth, a CEO with zero understanding of the state we are in, and a central banker who thinks their work is done. On the latter, I am still firmly of the view that the RBNZ should have all but closed up shop for four years in March 2020. We would all be better off.

I am really looking forward to lower mortgage rates mid 2025. It’s been a real slog in 2024. I tire of hearing my brother in Sweden having ‘high’ interest rates of 3.8%, and my brother and sister in law paying less than 3% in Japan. We are getting flogged on multiple fronts in this country

Interest rates are a risk premium. Risk differs between countries, and so will mortgage rates. There's no reason we should expect ours to be the same as anywhere else, or to think we're being hard done by if they're not.

True, but My point is it seems that in this county we get whacked on so many cost of living fronts. Including high mortgage rates. If I was 10 years younger, and not bound by the commitments I am bound to, I would be out of this place yesterday. We are at the high end of middle income as a household, yet it’s a struggle from pay day to pay day. Life is too short really

I agree. I have been reluctantly dishing out the same advice to fresh graduates for a while.

The issues with a small, simple, inward-looking economy is that broad economic developments (interest rates, fiscal policy, etc.) permeate through the system rapidly and affect almost everyone's finances.

Where would you go? I recently applied for, and was offered an interview for, a job in HK. It would have been an extra 2k/fn after tax to what I'm currently on. But factoring in the insane cost of living, less annual leave, and lack of things I love about NZ such as quiet, clear nights to stargaze, I concluded the grass wasn't so much greener, so didn't follow through.

Australia or Canada. If I was 10 years younger, today, I would also seriously consider living in Japan (working remotely, with a bit of on the ground work there)

All three countries have natural environments at least as good as NZ’s. It’s an overrated attribute

Singapore I've found to be a great option on many fronts

To be fair HouseMouse, you also bought a house in one of the most expensive suburbs in the country, that isn’t easy anywhere.

You mention Australia and Canada, you would really struggle to buy a townhouse in the best suburbs of those countries on the high end of middle income. Not saying that’s necessarily comparable as they are bigger and more desirable countries. But at least it is doable here.

I most certainly didn’t do that. We bought in a low-middle value area, close to middle-high value locations. And as you know I am not just talking about house prices, in terms of cost of living.

My bad. What suburb are we talking? I got the impression you were close to the CBD, Mt Eden area.

Tamaki. ‘Glenn Innes Heights’ 😂

Funny how one can make assumptions!

I agree Japan is a good option. But i do wonder about the quality of life. Japanese friends over there were amazed that i could take weeks off work to go travelling. But I do like Japan, it would be on my list.

As for Australia, it probably has to be one of the best countries in the world to live in right now. But its not perfect either

As for Canada, I assume you aren’t talking Vancouver as that is hideously expensive? I have only been to Vancouver, I thought it was ok but then they have challenges that make Auckland look safe People injecting up in the Main Street was the norm.

If you can’t name 20 countries that are better, maybe you actually have it pretty good?

There’s no universal truth on where is ‘best’, there’s obviously lots of variables. And everywhere has its cons as well as pros. But for plenty, one can get financially much further ahead in Aus than NZ:

https://www.stuff.co.nz/politics/360513460/embargoedaussie-brain-drain-…

Canada? I quite like Toronto. Vancouver, take or leave it.

I think Scandanavia offers a better quality of life than here. Although the winters are hard!

I agree, Aus would probably work out better financially. As for Scandinavia, TBH I’ve only heard bad reviews from friends, but that is a sample of 2.

But I still think NZ is probably in the top 10 countries to live in, so we are probably a bit hard on ourselves.

Might just sneak in top 10

For me the big cons of NZ are:

- ultra high cost of living (relative to incomes)

- pretty lousy and under capacity healthcare system

- distance from most of the world (I realise some see this more as a pro than a con - not me)

- poor transport options

- career opportunities at times narrow

The pros:

- generally pleasant environment, and lots of natural beauty across fairly small distances

- generally good, temperate climate

- generally friendly populace

- overall I think the education system is quite good

- it’s home

A lot of it comes down to how you want to live your life. If you want the absolute best of metro living, then it's pretty far down the line, and likely always will be. Well, unless things get really kaka in many other regions.

Sweden and Japan have some of the highest savings rates in the world, multiples higher NZ's. All that surplus capital usually gets lent/invested back to households, businesses and governments at cheaper borrowing rates than what offshore lenders are willing to offer.

Also, households and businesses in those countries generally have stronger balance sheets bolstered by high saving rates, so the risk premium on mortgages is relatively lower.

Having said that the Japanese house hold savings rate has collapsed in the last couple of generations from over 20% to now under 5%.

Those high savings rates are a result of trade surpluses and / or high govt deficit spending. That's literally what fuels the savings!

In NZ, our current account deficit and low deficit govt prevents us clocking up savings. Our growth is sustained by expanding the private sector balance sheet.

Those high savings rates are a result of trade surpluses and / or high govt deficit spending. That's literally what fuels the savings!

Agree / Disagree. There are cultural aspects at play here too. Even during their epic bubble, low-/mid-income people were generally savers. Paycheck to paycheck people were the lowest in the socio-economic pecking order. Usually outcasts who worked as what was called 'day laborers' who ironically played their part in Japan's economic development. They were usually single men who migrated to the cities to work in construction, etc and lived in districts full of cheap hotels that catered to their existence.

Japanese saved in very low interesting bearing post office savings accounts because it was 'safe.' The Ma & Pa property investor class doesn't really exist and people didn't really invest in stock markets.

Culturally Aotearoans were much more fiscally conservative as well. Up to the mid-80s.

The net saving rate used for these stats is the *net* increase in private sector savings - ie what households have banked net of what they have borrowed. In NZ, our savings rates are low because our savings come from increasing debt so they kind of don't count.

In Japan (for eg) their savings come from their trade surplus and govt pumping public debt into the economy. The private sector stacks that cash. Of course, part of this is cultural, the Japanese do save more, but they can because the rest of the world and the govt run a deficit.

Yes, but if you look at broad money supply between Japan, US, and the EU, the annualized rates of broad money supply increase per capita (2002-2021):

- United States: 6.2%

- EU: 5.5%

- Japan: 2.9%

I think that's a pretty good indicator of Japan's comparative propensity to save (not accumulate debt) among firms and h'holds.

Yes, so how can Japan save without accumulating private debt? Because Japan runs a trade surplus and the govt has very high debt!

Japan USED to run a trade surplus. They have been hitting record trade deficits and are in their final financial countdown now.

Great comment. We're underestimating the loss of economic capacity, given the ongoing exodus of productive Kiwis and enterprises, at our own peril. This grossly limits our ability to stage an economic recovery in the foreseeable future.

The OECD recently pointed out that migration into NZ has been mostly low-to-medium skilled and IMD put NZ at #63 out of 68 countries on brain drain in the the World Competiteveness 2024.

She’ll be right

Jfoe, I'd like to offer a counter argument.

Whilst I understand that we all want an easy life, and we don't like to tighten our belt, perhaps it's not such a bad thing to have a proper recession, weed out the inefficient businesses and people in order to restart with good, quality products and services. We have kicked the can down the road and refused to take the medicine for too long. Perhaps it's time to get real, work hard and well, treat customers, staff, bosses better, rather than continuously hope monetary and fiscal spending will save the day?

I guess the argument against that is the governing authorities don't enact economic Darwinism uniformly.

But yes expecting every harvest to be the same or more bountiful as the past is unrealistic.

"weed out the inefficient businesses and people in order to restart with good, quality products and services"

Good theory, if only that was how it actually worked

That's exactly how it works. In tougher situations the good operators remain, the bad ones don't.

I agree with you Yvil.

We need a recession to clean out bad debt, shit operators, specuvestor idiots and take our medicine.

We also should have much stricter credit control to dampen future episodes.

If you can’t build a small / mid business without eye watering bank debt, you shouldn’t be allowed to play in the first place.

There you go, pour yourself a steinlager.

Weeding out the inefficient people? Is this 1930s Germany?

As for weeding out inefficient businesses, that is not what happens. We just lose businesses in sectors vulnerable to drops in disposable income or confidence. Construction, clothing, retail hospo etc. How many inefficient New World stores have we lost? Have the worse aged care residences closed?

While we might not miss some of the lost retail capacity much, the lost construction capacity will hurt.

As for weeding out inefficient businesses, that is not what happens. We just lose businesses in sectors vulnerable to drops in disposable income or confidence.

Both occur; we will generally loose the weakest players in whatever sector is feeling the pinch. And potentially any businesses who might supply or work with said businesses, depending on their viability also.

The construction businesses falling over are more likely to be ones that've had tenuous profitability, for varying reasons. Business that operate a decent set of books, who have diversified and are more flexible to change are more likely to survive and prosper.

I am not discounting that position totally, but it is hugely overplayed. We lose businesses in vulnerable sectors that do not have *market power*. So we keep businesses with public sector contracts, or the ones that rely on another family business for contracts, or ones that are the only business of their type in a rural area. Market power is not the same as efficiency and as businesses without market power go to the wall, what happens to the market power of the others?

All in all, the idea that recessions weed out the weak businesses is deeply flawed.

Those once secure public sector contracts are not being renewed as we speak. But good points overall: who you know remains one of the biggest factors in business survival in tough times, not "efficiency".

Some "weak" business operators fold simply because they see their industry as structurally weak. The cyclical nature of construction for example is brought about partly because of the idiocy of indirect participants- think politicians, euphoric speculators and the banking industry as a whole.

All in all, the idea that recessions weed out the weak businesses is deeply flawed.

It's mostly true. Really well run businesses can usually withstand 2-3 years of adverse trading conditions. If the adverse conditions are longer than that, you probably need to change your model.

"As for weeding out inefficient businesses, that is not what happens"

I can't believe, you, Jfoe, wrote this. Of course that is exactly what happens, and you know that the good operators will survive in a tougher environment and the weaker ones won't, there's no need to reinvent the wheel.

He’s definitely at least partly right.

look at all the dinosaurs that survive recessions, simply because of monopoly powers and/or cronyism.

As my next comment said, I am not totally discounting your pont. I just don't think that efficiency is the primary determinant of who goes to the wall in a recession. As is so often the case, the reality and the theory are quite different.

It's not just about efficiency though. It's also about a businesses debt levels, other liabilities, and how close to the bone they're trying to run their business model - the overall quality of the business, of which efficiency is but one part. The worst businesses overall are most likely to fall over first.

A business that tries to use low margin pricing as a competitive advantage, for instance, is going to struggle on lower revenue. Their model doesn't have as much resilience.

Do you not see the contradiction here? We complain about companies who get away with profiteering and lazy practice because they have market power. We want companies to compete - to disrupt and use low margins and investment in productivity gains to displace the old guard. Then, who fails in a recession? The fat cat or the contender?

Shaving margins isn't disruption. It's buying a market in the hopes to make up for things with volume. Disruption is mostly a new way of operating, that supercedes the status quo via a superior product, or much more cost effective operating model.

And an economic downturn is often the death knell for established fat cats, in the face of genuinely viable disruptive businesses.

I'd wager most businesses falling over during a period like this, will want to blame an external authority, but there were always underlying weaknesses in the business. They just got exposed by the adverse conditions.

A question everyone should ask themselves is who stops spending in a recession?...The poor who have little to no discretionary spending power recession or no?....the wealthy who have the opportunity to purchase more assets at firesale prices?....or perhaps the middle class who find they are losing the ability to pay their bills?

Identify the businesses servicing that cliental and you will identify the businesses that fail....efficient or not.

As the saying goes, its made round to go round....but first you have to have it.

Things are usually more indiscriminate than that

The great Scottish economist Kevin Bridges suggests we should increase benefits because that demographic will go out and spend every last penny. From memory he suggests each beneficiary should be given 1000 pounds a week which I guess would be about NZ$ 2,000 a week. he reckons that would get the economy bouncing. He also suggests that savers are actually damaging the economy.

Let's build the economy by spending and borrowing more, not by saving and investing more.

OK then can we try this for a few years and see how it goes

I think businesses that service the middle class can do very well in boom times, less so in bust times. Low end and high end tend to be more resilient. Seen a few ‘trendy’ middle income type food haunts vanish recently. I noticed today that my old fave Tiger Burger has gone. Can probably add gourmet burger joints to craft beers as a ‘bubble economy’ trend that is turning boom to bust.

And I’ll offer the middle ground. I think the current system would have worked well had the RBNZ not lowered to 0.25% nor raised to 5.5%. They have been very reactionary (world wide) and then they give the lever a good yank instead of a little caress.

It was clear by Q4 2020 that house prices were going nuts. It could be considered negligent that firm steps weren't immediately taken to rein in the speculators and the lenders.

Also negligent that the FLP was continued so long after this

What the hell is it about kiwi culture that makes us prone to these spells of self-flaggelation?

Nothing unique, it's human nature to persevere with the familiar. Overcoming fear of change, and implementing the will and motivation to carry it out are not easy for us to materialize.

We are going to need to be under extreme conditions to make any substantive changes.

All true but would suggest that the RBNZ (and Gov) actions merely bought those impacts forward with their interest rate increases....the discretionary spend was already under pressure as were the conditions that are driving emigration....and after 2 years we are continuing on the same path to the same destination.

The RBNZ could have sat on their hands but the 'favour ' would have done us would have been temporary....and that applies regardless of 2023 election result and mini Ruth, poor as they are.

Its structural, and needs radical reform that is not on offer.

So, we blew the country up to put out the fire? What a great strategy.

Agree on the structural reform obviously.

Didnt say it was a great strategy, simply that they didnt cause something that was happening anyway....they advanced/accelerated it.

Central banks dont control distribution and that is where the issue lies.

Yes, sorry, got you.

Do you know why there’s such a difference between the unemployment rate and those on welfare? Seems to me that it’s essentially a royal fudging of the statistics that no party is willing to straighten out on their watch as they will be “blamed” for a massive rise in the unemployment rate. However if they were measured correctly we would have different policy both fiscal and monetary.

It'd be interesting to know the international discrepancies in measuring employment (or unemployment). We have lower than global or OECD unemployment rates, but it can be hard determining if that's like for like. I'd imagine the figures in countries with much less social welfare infrastructure don't reflect the same.

I have been retired for 22 years so have no feel for the market, but my younger son is GM of a trucking company which is part of a big multi-national and he is seeing no signs of an upturn.

The team is being kept together, but other costs such as travel are being cut heavily. he doesn't expect any significant upturn until later next year.

‘25 is going to be another tough year

Just a shoutout - can we reflect on how dim the DGMs were about HFL? LOL

hope people reflect that any views people on here give should be taken with a tiny grain of salt.

Hang around long enough and you see very few actually change their mind about anything.

The comment traffic is about 90% looped soundboard, and 10% objective appraisal on a topic by topic basis.

How much longer is Orr in charge for?

Asking for a nation.

My two biggest concerns are the quality of people leaving New Zealand for good, and that after all this, there is no clarity around infrastructure investment.

Well my biggest concern is climate change and insurance risk, but having seen right wing governments campaign and win on that its all nonsense I've given up hope of meaningful action.

No such thing as leaving NZ for good. The world has entered a stage where everything is now changing rapidly, peoples priorities are going to shift. My recommendation is that you hang onto a current NZ passport at all times.

And then complain bitterly in a time of global crisis that you can't get back quick enough?

Of course and clearly things can get bad enough, fast enough for them to close the borders. People need to think about the big picture ahead of time, like for instance now.

This is extremely good advice. If at all possible stay in New Zealand through next year and certainly try to avoid making trips to places like Poland, Romania and Taiwan if possible...

Yup, spend your adult life working and paying taxes in other countries and then complain that you can't get back quick enough, or that Journalist who was swanning around Afghanistan that found out she was pregnant in Qatar (where it's illegal to be pregnant while unmarried), complaining she couldn't get an "emergency" MIQ spot because she wanted to return in a month's time instead of the criteria of within 14 days.

No wonder I left this hellhole!

But can I come back for a bit please while everywhere else is worse.

My two biggest concerns are the quality of people leaving New Zealand for good

Statistically it leans towards those who can't make it work well enough in NZ. The most experienced, top performers in any field are the best remunerated, so outside of those who have very high economic aspirations, migration is usually dominated by a gutting of the middle.

I would have to agree. The problem is that everyone's expectations now is pretty much even regardless of their skill set.

It has been interesting over the years watch changes in work approach.

There's great jubilation today having managed to do anything. Whether it's done well, or efficiently takes a distant second place. Likely part and parcel a combination of declining standards of excellence, demands for higher frequency (things get rushed), and way too much multi-tasking.

Declining standards may have something to do with the ability of the wider populations capacity to afford it.

Likely partially true. Although I see a fair bit of mediocrity performed under relatively open checkbooks.

Sloppy, careless work is a reflection of low professional standards, mediocre educational process and poor personal pride. And there is plenty of that now embedded in society at every level. TL/DR the culture is slowly disintegrating.

Great opportunity for anyone with even a slightly better than average approach though.

Precisely. And that's what I tell my kids.

Sadly, my wife couldn't make it work in NZ. But, that's a reflection of those in charge of her professional body and the poor remuneration they offer.

I'm surprised NZ has any nurses, teachers and police officers left - my guess is those who remain are either a) older and own property bought cheaper, or b) younger and simply can't afford to leave [or c) imports]. I'm sure there's other less financial reasons (loyalty to family, say) but I'm leaving them out for narrative purposes ^^.

PS. I agree with you, my point is that 'those who can't make it' is not necessarily about the person. I believe the statistics also show those willing to undergo the upheaval of emigration are usually willing to put the yards in to make it work (isn't that what NZ is relying on with cheap imports a dozen to a house?).

Yeah I guess there's a caveat to what I said, if you are working as part of a larger workforce with only a handful of employers, and standardized salaries.

You could be the absolute best traffic cop in the country, but outside of better chances from promotion, you're not going to earn much more than someone who's spending their day trying to avoid doing too much.

“Well my biggest concern is climate change ………………I’ve given up hope of meaningful action.” Largely those right wing governments are of nations somewhat financially stricken and now the largest of the lot has Trump. It unfortunately may now mean a posture of, we just can’t afford to take any meaningful action.

I am still fascinated by people being terribly concerned about climate change wrecking havoc upon us in a few decades or perhaps a century or so, and ignoring the fact that a new generation of escalating nuclear conflicts is right in front of us able to destroy civilisation as we know it in under ninety minutes. At least fossil fuel use will be down afterwards?

A potential of that catastrophic magnitude does not need any more publication and/or escalation. Of the nuclear armed nations Russia and China are both being operative, and bellicosely so in that regard. Russia’s claim of right to use in the face of an existential threat is fuel on the fire as the actual definition of that threat, is open ended. An unintended consequence that it affords Israel likewise, such a precedent. You are correct. The risk and consequences cannot be understated.And now in the USA there will soon, be in place the most unpredictable President ever known.

Nuclear wars *might* happen, but climate change is definitely happening and causing increasing havoc now. it is not just a problem that's going to start in a few decades.

I am still fascinated by people using whataboutisms to justify doing nothing.

Yes it is sad to see people applying prioritisation and context to the various problems we face instead of running with jingoism.

Yes, but what about the people doing less than nothing? And the people doing too much that we need to balance out? And what out that new disease in the DRC? Pass me a steiny.

Kiwi's have very short memories. No body ever looks back and seeks - or demands - answers to the same problems we'll face again and again. Some extremely pertinent questions can be asked ... But Kiwis won't seeks answers, nor fixes.

My questions for the RBNZ:

- Did the RBNZ act prudently at the beginning of COVID by dropping the OCR to 0.25%, dumbing LVRs, throwing cheap money at retail banks, etc.?

- Did the RBNZ act prudently leaving all that monetary stimulus in place for so long when it was crystal clear broken supply chains and extremely cheap money was pushing up inflation?

- Did the RBNZ act prudently holding the OCR so high, for so long, when it was evident an energy shock and a cyclone induced local supply shock (both short tail events) were, together with their extremely lax monetary policy, the source of inflation?

- Does the RBNZ believe they are being honest with Kiwis by not fully acknowledging the full impacts of their use of the OCR? I.e. their use of the OCR to control inflation creates winners and losers. How about the RBNZ comes clean with exactly who those winners and losers are? At present they say, "some people will lose their jobs and a few businesses will fail". This is an unacceptable level of detail. Time for the RBNZ to come clean with far more detail - especially with how much rises in the OCR actually add to inflation (See JFoe's comment).

My questions for the Government of NZ:

- The RBNZ is subject to virtually no oversight by anyone with adequate skills to evaluate their performance. Does the Government of NZ believe they are fulfilling their obligations to all Kiwis allowing this to continue?

- Does the Government of NZ believe they have no tools that could be used to immediately address inflation thereby meaning inflation is solely a job for the RBNZ?

- Does the Government believe it is fair and equitable that younger people with mortgages bear the brunt of the RBNZ's inflation fighting actions? Would it not be fairer for Government to facilitate 30 year fix rate mortgages like is done in the USA?

- Does the Government believe it is fair and equitable to ensure mortgages for business purposes were in fact at business interest rates - thereby bringing owner occupier mortgages interest rate costs down?

- Does the Government believe it can't do anything about imported energy shocks that immediately sends NZ's inflation rocketing up? What research has Government carried out to conclude there is absolutely nothing that it can do? Further, what policies does Government have to lessen the effects of these shocks?

Really great post

Too bad we don’t have any one in high places, nor in the media, asking these probing questions

Yes good post. One caveat, you can get 5yr mortgages in NZ, but many would rather not pay the extra so take the risk with short rates. BNZ did a 7yr mortgage at one stage but canned it as it wasn’t popular.

NZ's 5-year mortgage - and the 7-year one - are just extensions of what NZ banks offer for 1-3 years. A 5-year mortgage carries more risk for the sole issuer thus 5 year interest rates are seldom attractive to mortgagors. But a 30 year fixed rate mortgage is a whole other story ...

In the USA, 30-year fix rated mortgages are packaged up and sold as bonds (mortgage backed securities). These get traded on bond markets that are both active and deep . (These markets are 5 times bigger than the US stock markets.) For example, in the US when Fannie Mae was created in 1938 by the government to strengthen the secondary mortgage market, Freddie mac was set up later (1970) by the government to facilitate an even stronger 'secondary market' where the securities could be bought and sold.

Thus NZ's 5-year fixed rate mortgages and the USA's 30-year fixed rate mortgages are effectively chalk and cheese.

NZ obviously has the chalk, whereas the USA has the cheese.

In the US, borrowers can have their cake (30 year fixed) and eat it too (they can break cheaply when interest rates decrease). Surely they must be paying for that privilege - the bond market is not a charity.

But I agree we should consider something similar. I just wonder in our small undesirable market if it will just mean high rates.

Perhaps one of the US banks should open a online branch here to allow kiwis to access their banking products.

If enough people asked, would Orr be sacked? I only asked 3x, myself.

ConF. Great hammer, great nails and great hitting thereof.

prudently

You don't get the option to exercise this when you're operating under emergency conditions with unknowable outcomes.

So it's sorta like how we took helicopter pilots to court for acting without prudence, trying to rescue people when White Island erupted.

Excellent post... and those are the questions that should have been asked by a committee assessing the economic component of our COVID response.

Sadly, our mainstream economic commentariat and the prominent advisors in Treasury etc have the same grossly simplistic (and often simply wrong) model of the economy. A model where govt spending is always and everywhere inflationary, private debt is basically ignored, and interest rates magically reduce inflation via the mythical expectations channel.

Not sure if you saw this - you'd like it:

https://www.grumpy-economist.com/p/monetary-ignorance-monetary-transmis…

John is on many 'required reading' lists.

The retrenchment of the stupidity of cheap debt takes out those that thought it would last for ever. Simply being crushed by their own greed on this they simply should have said "no" to.

Banks laughing all the way to their owners bank.

Most of the people crushed were simply trying to buy homes for their family.

To be fair, the absolute consensus 4 years ago was that cheap rates would last forever, deflation was never going away, we were turning Japanese, etc. Almost no one was picking inflation and 5.5% OCR.

Exactly

"Almost no one was picking inflation and 5.5% OCR. "

Not actually true.

I guess the saturation level of commentary the bank economists get might have led many to form this view. (Lazy MSM and lap-dog independent journalists parroting - but never questioning - have much to answer for. They're part of the bigger problem.)

But the reality is the bulk of the non-bank economists had very, very different views.

Great thread peoples. It's past 9 oclock & I'm heading to my bed. My only contribution is to say "watch the ball." For us[me] that's all we [family business] can do. There are many things happening beyond our control & I/we can only make a difference to what we are doing. Globally we are insignificant. As a small nation miles from anyone else, we are an after-thought at best. We do alright for a few hard workers & a bunch of beneficiaries but yes, there are many things we get wrong despite that. I started my working life in a recession in the 1970s. It looks like I will finish my productive years in a similar mode. There were also a couple of recessions in the middle, but I/we are still here. Hardship is never nice in whatever format it comes with. The thing about knowing how good good is, is knowing how bad bad can get. And we are nowhere near that in NZ. There are more than 150 countries out there where life is bloody hard most of the time & we don't even talk about them & we don't know them, but they're there, believe me. We may be at the bottom of the top 20 [30?] but that's still a good place to be. Especially for a small fart-arse country at the bottom of the Pacific.

Nice place to live ... but crap place to invest = going down

We need a snap election to get rid of the inexperienced amateurs pretending to govern

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.