This is a re-post of an article in the RBNZ Bulletin, 31 January 2023 – Vol. 86 No. 1. It is here with permission.

By John Knowles, Laura Austin, and Lewis Kerr*

Introduction

Money plays an essential role in the economy. It allows people to store value over time, exchange with each other, and measure the relative value of things. The Reserve Bank is responsible for maintaining people’s trust in money. Trust and credibility are central to the idea of money, without which, the economy could not run smoothly and people would be much worse off. The Reserve Bank tries to keep the purchasing power of money steady by keeping consumer price inflation low and stable.

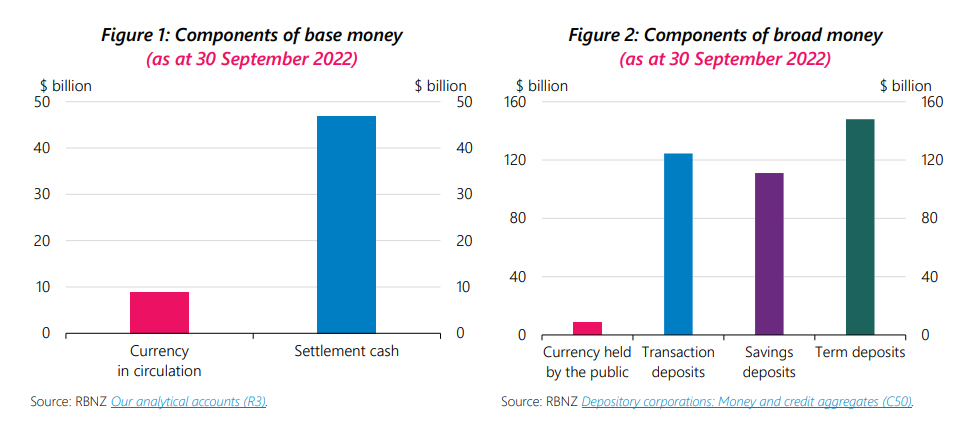

There are several forms of money. Some are created by the Reserve Bank directly, and others are created by commercial banks via interactions with their customers. Money created by the Reserve Bank directly is known as the monetary base, base money or M0. The monetary base includes physical currency (notes and coins) and settlement cash balances (figure 1). Settlement cash balances are deposits held by commercial banks in their accounts at the Reserve Bank.

However, the monetary base is small relative to the total money supply. The money most people use in their daily lives is known as broad money, also known as M2. Bank deposits make up about 98 percent of broad money in the New Zealand economy (figure 2).

The Reserve Bank conducts monetary policy by influencing short-term interest rates to maintain price stability and support maximum sustainable employment. The Reserve Bank’s monetary policy influences the quantity of broad money, but does not directly control it. This article will describe the monetary base, explain how broad money is created through the bank lending process, and explain the constraints on broad money creation. The final section explains how additional monetary policy (AMP) tools affect the quantities of base money and broad money. Commentary on monetary policy’s contribution to recent economic outcomes can be found in our recently published Review and Assessment of the Formulation and Implementation of Monetary Policy.

The monetary base

The monetary base is made up of settlement cash and physical currency in circulation. Settlement cash can only be held by registered banks with accounts in the Reserve Bank’s Exchange Settlement Account System (ESAS). ESAS allows banks to settle transactions between each other and with other ESAS participants such as the Reserve Bank and the Crown. ESAS forms an integral part of how payments are made and settled in New Zealand, which is discussed further in New Zealand’s payment landscape: a primer. Only ESAS account holders can hold, borrow and lend settlement cash; it cannot be ‘lent out’ to the general public.

Settlement cash currently makes up over 80 percent of the monetary base, with the remainder consisting of physical currency. There is currently just under $9 billion of physical currency in circulation, held by households, businesses and commercial banks. Commercial banks can use settlement cash to buy physical currency from the Reserve Bank to meet the physical currency needs of their customers. Bank customers withdrawing physical currency don’t change the quantity of base money, but do increase the quantity of broad money. This is because physical currency held by a bank is counted only as base money, but physical currency held by the public is counted as both base money and broad money.

Figure 3 illustrates the usual ways base money can move around. Up to date data on these balances can be found in Our analytical accounts (R3).

The total amount of settlement cash held by banks in ESAS is known as the settlement cash level.

Banks can raise or lower their own settlement cash balances by transacting with each other, the Reserve Bank, or the government. However, transactions between banks do not change the total settlement cash level.

For example, if Laura at Bank A makes a transfer to Lewis at Bank B, Bank A will tell the Reserve Bank to transfer money from Bank A’s ESAS account to Bank B’s ESAS account. This decreases Bank A’s settlement cash balance, increases Bank B’s settlement cash balance, and leaves the total amount of settlement cash unchanged.

Only transactions involving the government and the Reserve Bank can change the settlement cash level. The government’s taxation and borrowing reduces the settlement cash level, whereas government spending and paying off debt increases the settlement cash level. The government’s account at the Reserve Bank is known as the Crown settlement account, and is not technically included in the settlement cash level.

For example, when John, a customer of Bank A, pays tax, Bank A settles the tax payment by transferring funds from Bank A’s ESAS account to the Crown settlement account. This reduces the settlement cash level.

As another example, let’s say KiwiSaver Fund A owns a government bond which is about to mature

— i.e. it is time for the government to pay back some of its debt. KiwiSaver Fund A is a customer of Bank A. When the bond is paid back, the government transfers settlement cash from the Crown settlement account to Bank A’s ESAS account, increasing the settlement cash level and base money. Bank A gives KiwiSaver Fund A a bank deposit of the same amount, causing broad money to increase.

The Reserve Bank controls the settlement cash level through its monetary policy tools and financial market operations. It has a range of tools which it can use to inject and withdraw settlement cash by transacting with banks, allowing it to ‘offset’ other factors that influence the settlement cash level — such as tax payments and government bond maturities. The Reserve Bank also provides facilities that allow certain banks and financial market participants to borrow and lend from the Reserve Bank.

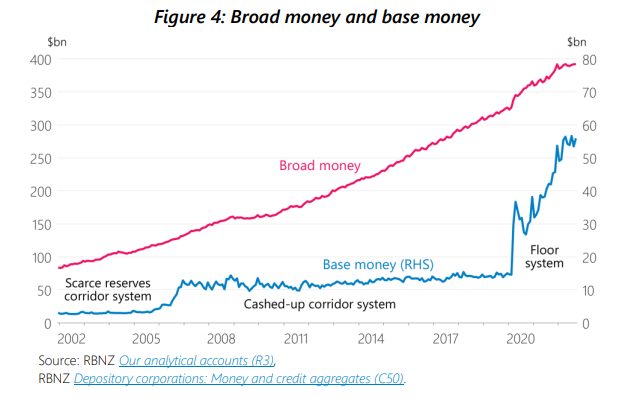

The Reserve Bank uses its tools and operations to keep short-term interest rates between banks close to the Official Cash Rate (OCR), which flows through to other interest rates in the economy. This includes by determining the interest rate paid on settlement cash balances and the nature and pricing structures of the Reserve Bank’s other facilities. This has been achieved in a number of ways over the years, with each regime having been associated with a different quantity of settlement cash (figure 4).

Monetary policy was implemented via a corridor system between 1999 and 2020. A corridor system means banks earn the OCR on their settlement cash balances up to a prescribed ‘tier’ — any balance held above a bank’s respective tier is paid at a level below the OCR. Between 1999 and 2006, the corridor system was operated as a ‘scarce reserves’ system, with only about $20 million of settlement cash left in ESAS overnight, as explained by Frazer (2004). The scarce reserves system required the Reserve Bank to be highly active in its market operations.

Starting in 2006, the system was ‘cashed up’ and operated with a settlement cash level of about $7 billion, as explained by Nield (2006). Since 2020, the introduction of AMP tools required a change to a floor system, in which short-term interest rates can remain near the OCR despite large quantities of settlement cash, as explained by Silk (2022). A floor system means the banks earn the OCR on all ESAS balances. The effects of AMP tools — the Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) programme and Funding for Lending Programme (FLP) — on the level of settlement cash are discussed in a later section.

Although the technical details of how these systems operate vary considerably, both the corridor system and floor system serve the same purpose of keeping short-term interest rates between banks close to the OCR. They do not change the stance of monetary policy, or affect the quantity of broad money, on their own.

Broad money creation

Broad money is defined as money available for use by the general public. This includes physical currency held by the public and commercial bank deposits. A bank deposit represents a bank’s promise to allow customers to withdraw physical currency, or transfer that deposit to someone else. Because people tend to leave most of their money in the bank, bank deposits make up the vast majority of broad money.

Bank deposits are created when banks connect borrowers and savers via the process of bank lending. Likewise, bank deposits are destroyed when customers pay debt back.

Example: broad money creation through bank lending

John wants to buy a house from Laura for $1 million, but must borrow $800,000 from the bank to do so. The bank trusts John, so it gives John a loan, which becomes an $800,000 asset on the bank’s balance sheet. The loan is a liability for John, but it is an asset for the bank. Simultaneously, the bank gives an $800,000 bank deposit to Laura, which becomes an $800,000 liability on the bank’s balance sheet. The deposit is an asset for Laura, but it is a liability for the bank. Laura also receives John’s $200,000 deposit. In the process, the bank’s assets and liabilities have grown, and $800,000 of new broad money has been created by the increase in deposits (figure 5). John will pay the loan back over time, which will gradually destroy broad money.

Some bank liabilities – like deposits – are counted as broad money, while others – like wholesale debt – are not. Therefore, the quantity of broad money can also change when banks choose to fund themselves differently. For example, when a bank issues a bond to investors, payment for the bond would transform some deposits into wholesale debt, thereby reducing broad money.

The limits to broad money creation

Money creation can be profitable for banks, because they charge more interest on loans than they pay on deposits. However, money creation is also risky for banks; if a bank makes a loan and creates a deposit, there is a chance the loan might not be paid back, but the bank must still honour the deposit. Since banks like to make profits, they will typically only lend when they think it is profitable to do so.

The amount of money created through bank lending is ultimately determined by the supply of and demand for bank loans. A range of factors will influence banks’ willingness to supply loans. Key supply factors that can constrain money creation include:

- Liquidity: banks need to ensure they have access to enough base money to satisfy withdrawals of deposits, or transfers to other banks, on any given day. As deposits increase, banks’ liquidity needs increase.

- Stable funding: when deposits are withdrawn by customers, or when wholesale debt matures, banks need to ensure they will be able to replace this with new funding. Banks need to ensure that enough of their funding is from stable sources, so that it can’t be withdrawn all at once.

- Capital: if borrowers are unable to repay their loans, banks’ shareholders lose money. Banks need to have enough shareholders’ equity to absorb potential losses and avoid the bank becoming insolvent.

The Reserve Bank has minimum requirements in place to ensure banks have sufficient liquidity, stable funding and capital, and banks make their own profit-maximising decisions within these limits. These are in addition to other supply factors, such as banks’ willingness to take on risk and the operating costs involved in providing loans.

The other important determinant of commercial bank lending is people’s demand for loans. Banks can only lend money to customers who want to borrow, have enough collateral security, and can afford the repayments. Customers’ desire to borrow depends on several factors, including the interest rate. Interest rates offered by banks depend in part on the cost of liquid assets, cost of funding and cost of capital. These costs are influenced by monetary policy and regulation, as well as a range of other domestic and international factors.

The amount of broad money created by banks depends on the level at which the supply of bank lending meets demand. The sections below discuss the factors affecting the supply and demand for bank loans in more detail.

Liquidity

As banks create more broad money deposits, the potential for large daily withdrawals increases, so they need access to more base money. Banks can ensure they have sufficient access to base money either by holding it as settlement cash or physical currency, or by holding other liquid assets which can be easily traded for settlement cash, such as New Zealand government bonds.

There is an opportunity cost to holding more liquid assets, since they tend to offer lower returns than the rest of a bank’s assets. When demand for liquid assets in the banking system increases, this further reduces the returns they provide, increasing the opportunity cost of holding them. Therefore, banks attempt to strike the most profitable balance.

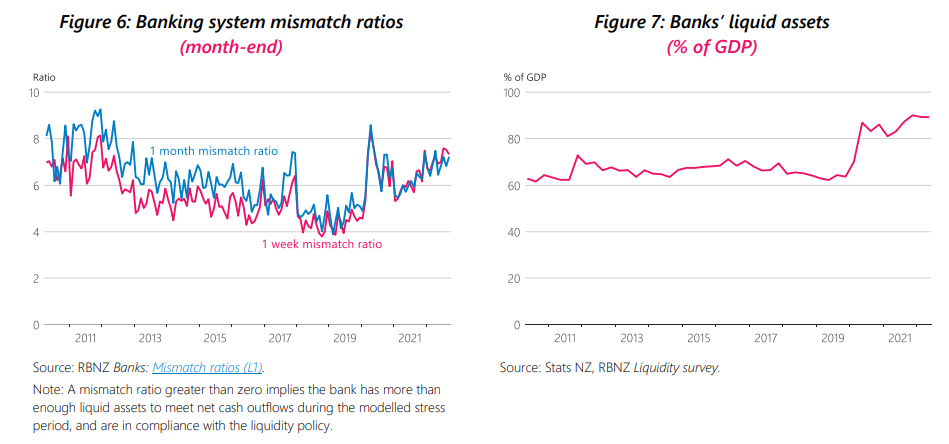

The Reserve Bank requires banks to hold a minimum level of liquid assets, relative to their size and funding composition. See the Reserve Bank’s liquidity policy for banks for a more complete explanation. The current liquidity policy requires banks to hold enough liquid assets to withstand both one-week and one-month periods of heightened withdrawals due to a serious loss of confidence in the bank. Since its introduction, banks have usually held liquid assets well in excess of the minimum requirement (figure 6).

A by-product of the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been an increase in the level of liquid assets in the banking system (figure 7), largely through an increase in settlement cash. This means that liquidity has been cheaper and more readily available for banks.

Since liquidity is not usually a binding constraint on bank lending, there is not a proportional ‘money multiplier’ relationship between the monetary base and broad money. However, this has not always been the case. Until 1985 in New Zealand, liquidity policies were more of a binding constraint on bank lending – see RBNZ (1985). A binding ‘reserve asset ratio’ meant there was a ‘money multiplier’ relationship between base money and broad money, which could be adjusted for monetary policy purposes. Under that system, it was more likely that an increase in the quantity of base money would have led to a proportional increase in broad money.

Over time, the reserve asset ratio was found to be an unreliable way of implementing monetary policy, because the relationship between the growth in the quantity of broad money and inflation was not stable. As central banks refined their inflation targeting toolkits, they moved toward setting the price of money — the interest rate — rather than the quantity. This culminated in the introduction of the OCR as the Reserve Bank’s primary monetary policy tool in 1999.

Stable funding

Banks fund their lending to households and businesses by borrowing deposits from customers and issuing wholesale debt — such as bonds — to investors (figure 8). In order to maintain their size, banks need to be able to replace this funding as it is withdrawn or is due to be paid back. Some funding is easier to withdraw, and other funding is more stable.

Banks have a strong incentive to ensure enough of their funding is from stable sources, because inability to replace funding would leave a bank unable to meet payments and withdrawals as described in the liquidity section above. In order to grow, banks need to secure more stable funding. Across the banking system, if banks demand more stable funding, this will push up its cost. Banks balance this cost against the profitability of new lending opportunities.

Further to banks’ own risk management, the Reserve Bank requires banks to source a minimum share of their funding from stable sources, usually deposits or longer-maturity wholesale debt. This is known as the core funding ratio, part of the liquidity policy described earlier. The core funding ratio can limit the rate of bank lending growth, and therefore broad money creation, because banks need to be able to grow their stable funding as they grow their lending. Banks typically hold a safe buffer above the regulatory minimum (figure 9).

Bank deposits make up the largest share of bank funding in New Zealand. For the banking system as a whole, bank deposits grow as a result of lending. However, this is not true for individual banks. Banks must compete with each other to retain their share of deposit funding, either by paying higher interest rates, or by offering safety and better services.

Furthermore, deposit growth does not need to precisely match loan growth over time. The difference can be made up by changes in wholesale debt. Wholesale debt can be sourced from within New Zealand or from offshore investors. Offshore bank funding is one of the mechanisms through which a small open economy such as New Zealand can borrow from abroad.

Capital

Bank capital mostly consists of shareholders’ equity, which is the owners’ stake in the bank. Broadly speaking, bank capital is equal to the difference between the bank’s assets and liabilities (figure 8). Therefore, capital is the first part of a bank’s funding to absorb losses if customers default on their loans. As a consequence, shareholders also demand a higher rate of return than other funding sources, making capital a more costly source of funding for banks.

The Reserve Bank requires banks to hold strong capital buffers, so that banks will be able to withstand large economic shocks. See capital requirements for banks in New Zealand for a more complete explanation. Banks can build their capital by receiving new investment from their shareholders, or by paying less of their profits out as dividends to shareholders.

Capital requirements limit the rate of money creation, because as banks grow their lending and deposits, they need to raise more capital to ensure they have enough relative to their lending.

Long-term growth of liquidity, stable funding and capital

Over the long term, banks can grow their lending without hitting a hard constraint or facing higher costs, even as they demand more liquidity, stable funding and capital. This is because, in the long term, liquidity, stable funding and capital available to the banking system are not in fixed supply, but are able to grow along with the economy. Households and businesses hold a range of financial assets, some directly and some via investment funds such as KiwiSaver. Although bank deposits are the initial by-product of bank lending, households and businesses will look to transform some of their deposits into other forms of financial assets. Through the financial system, this can increase the supply of funds available for investing in bank capital and stable funding — such as bank shares or bank bonds. In the long term, this allows banks to expand their stable funding and capital without having to entice investors through higher returns, which would push up their costs.

Demand for loans

Banks cannot lend unless customers are willing and able to borrow. Therefore, the amount of broad money created depends on where supply meets demand. Demand for loans in an economy depends on a range of factors, including:

- The borrowing needs of the population as people progress through different stages of their lives. People are typically savers when they are young and old, and borrowers through the middle of their lives. Connecting borrowers and savers is a particularly important part of the banking system’s role in the economy.

To draw on the earlier example in which John bought a house from Laura: John is in a relatively early stage of his working life. Most of his income will be earned in the future, but he needs a house to live in today. By borrowing from a bank, John is able to use his future income to purchase a house, which he will live in for a long time.

Meanwhile, Laura is nearing retirement, and will downsize to a smaller house. Her bank deposit allows her to store the value of her past work, and use it to pay for living costs many years after she stops working.

- The overall size of the economy — which reflects both population size and incomes.

- The availability of profitable opportunities to invest in economic capital, such as factories, equipment, or education. These investments cost money today, but are likely to lead to higher income in the future.

- Prices of physical assets, such as houses. These affect how much people need to borrow as they progress through different stages of life.

- Interest rates, which influence the above decisions around borrowing, saving and investment.

Therefore, the overall demand for loans depends on many individual households and businesses making decisions for their own unique circumstances. Over time, central banks have found that setting interest rates — the price of money — rather than targeting some quantity of money, is the most effective way of implementing monetary policy to affect economic activity and inflation.

The effect of additional monetary policy (AMP) tools on the quantities of base money and broad money

The Reserve Bank’s primary monetary policy tool is the OCR. However, there is a limit to how low the OCR can be set, and from time to time AMP tools are required in order to provide the level of stimulus necessary to meet our inflation and employment objectives. During the COVID-19 period, the LSAP programme and FLP were deployed. A more complete description of these tools is provided in a Bulletin on the Reserve Bank’s AMP toolkit. Here we will describe the ways these tools affect the quantities of base money and broad money.

Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) programme

Under the LSAP programme, the Reserve Bank creates new settlement cash to purchase government bonds from the market. Since government bond yields serve as a benchmark for longer-term interest rates in the economy, bond purchases have the effect of lowering longerterm interest rates.

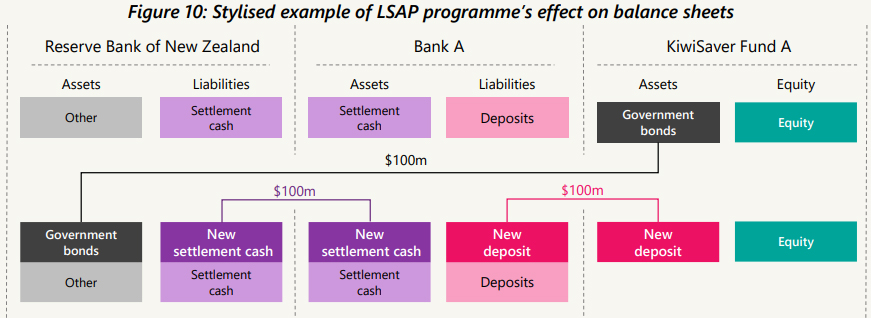

The LSAP programme has a direct effect on the quantities of both base and broad money because of the way the Reserve Bank carries out the asset purchases. A large share of government bonds are held by companies that are not banks, such as offshore investors, insurance companies and KiwiSaver funds. Since these companies do not have access to ESAS, the Reserve Bank must use banks as intermediaries.

Example: balance sheet effect of LSAP

For example, say the Reserve Bank wants to purchase $100 million of government bonds from KiwiSaver Fund A, which is a customer of Bank A. Bank A will credit KiwiSaver Fund A’s deposit account with $100 million in exchange for the government bonds. This makes Bank A’s balance sheet larger, and increases broad money. The Reserve Bank will pay for the government bonds by creating $100 million of new settlement cash, which is credited to Bank A’s ESAS account. This makes the Reserve Bank’s balance sheet larger, and increases the monetary base (figure 10)

In the example above, Bank A is acting as an intermediary between the Reserve Bank and KiwiSaver Fund A. The additional settlement cash created through the transaction is a by-product, and does not provide monetary stimulus by itself. Although Bank A will earn interest income on the new settlement cash held in its ESAS account, it also pays interest on the corresponding liability to KiwiSaver Fund A.

The immediate dollar for dollar increase in deposits will not necessarily last. For example, Bank B may decide that deposits are now too large a part of its funding mix, and eventually rebalance its funding composition to include more wholesale debt. The KiwiSaver fund may also decide it doesn’t want to leave so much money sitting in a bank deposit, instead choosing to invest in assets with higher returns. This could lead to a range of flow-on effects. For example, the bank could issue a long-term bond — which counts as stable funding — which the KiwiSaver fund could purchase. This would lead to a reduction of deposits in the banking system, and therefore a reduction in broad money.

The LSAP programme can also lead to increased bank lending and broad money creation by lowering interest rates and stimulating economic activity.

The wind-down of the LSAP programme will indirectly reduce the monetary base. Over the coming years, some of the Reserve Bank’s LSAP bond holdings will mature, and some will be sold back to the government. When the government bonds mature, or the Reserve Bank sells them back to the government, this will not directly affect the settlement cash level, because commercial banks will not be involved in these transactions. However, the government is likely to need to fund these maturity payments and buy-backs by issuing new bonds or using tax revenue, which would both decrease the monetary base.

Funding for Lending Programme (FLP)

The FLP is a monetary policy tool intended to lower overall bank funding costs, and therefore retail interest rates. Under the FLP, banks may borrow a set amount of money from the Reserve Bank at the OCR. To reduce risk, the Reserve Bank requires banks to provide high-quality collateral, such as government bonds, as security. FLP loans lower banks’ funding costs directly, since the OCR is cheaper than most other sources of bank funding. It also lowers funding costs indirectly by reducing banks’ demand for other sources of funding.

The FLP has a direct effect on the quantity of base money.

Example: balance sheet effect of FLP

For example, say Bank A requests to borrow $100 million under the FLP. The Reserve Bank will credit $100 million settlement cash to Bank A’s ESAS account, thereby creating new settlement cash and increasing the monetary base. The $100 million Bank A has borrowed is charged interest at a floating rate, equal to the OCR. Bank A may borrow the funds under the FLP for up to 3 years. After 3 years, Bank A will repay the $100 million to the Reserve Bank. The $100 million settlement cash is paid back to the Reserve Bank, decreasing the settlement cash level (figure 11).

Bank A’s FLP borrowing does not have a mechanical effect on broad money. However, by lowering interest rates, stimulating economic activity, and encouraging lending growth, the FLP can lead to an increase in broad money.

Conclusion

The vast majority of money in circulation is created by commercial banks, through the process of bank lending. The Reserve Bank has direct control over the settlement cash level, but this only has an indirect influence on the quantity of broad money in the economy, and is not particularly relevant for the transmission of monetary policy under the current framework. The use of AMP tools has caused a significant increase in the monetary base over the COVID-19 period. The monetary base will steadily decline over the coming years as the AMP tools are unwound.

The quantity of broad money growth depends on many factors, including the borrowing needs of the population, the availability of quality investments, the prices of physical assets, and interest rates. Various monetary policy tools have different effects on the quantities of base money and broad money. However, the purpose of these tools is to influence interest rates facing the real economy, in order to achieve low and stable inflation and support employment near its maximum sustainable level, rather than control the quantity of broad money.

* John Knowles is a senior analyst, Laura Austin is a senior analyst, Balance Sheet Design, in the Financial Markets group, and Lewis Kerr is an economic adviser, all at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand

Notes and References are in the original document here. This article is an update of this much earlier explainer.

31 Comments

Great explanation, thank you!

This article shows how reliant our whole monetary system is on housing. The example about an $800000 loan (paid back over time), as a bank liability. Question: most investment properties are interest only right? How does a bank mitigate risk in a falling market? Do investors get a dreaded email to swap over to principal, or is there a recognised equity threshold prior to that happening?

An update of a 2015 think piece, and the graphs and writers just updated? Call me a cynic, but one way to bed new staff in at each years' intake (about now) was to give them an older report and ask them to update it and add any new ideas. That both gave them something to do whilst they settled in, and might throw up something new that's being taught at where it was they came from. Regardless, is New Zealand any different to the USA...

"One important contributor to the resilience of the economy so far has been the enormous accumulation of excess cash that resulted from the COVID-19 stimulus....analysts put the peak of excess savings at $2‒3 trillion in late 2021. This excess savings balance has been slowly drawn down over the course of 2022, but less than half now remains. Once it runs out, by some estimates around mid-year, this particular support for the economy will be gone.”

https://images.mauldineconomics.com/uploads/pdf/TFTF_Feb_4_2023.pdf

The rate of interest – the price of money – is said to be a key policy tool. Economics has in general emphasised prices. This theoretical bias results from the axiomatic-deductive methodology centring on equilibrium. Without equilibrium, quantity constraints are more important than prices in determining market outcomes. In disequilibrium, interest rates should be far less useful as policy variable, and economics should be more concerned with quantities (including resource constraints). To investigate, we test the received belief that lower interest rates result in higher growth and higher rates result in lower growth. Examining the relationship between 3-month and 10-year benchmark rates and nominal GDP growth over half a century in four of the five largest economies we find that interest rates follow GDP growth and are consistently positively correlated with growth. If policy-makers really aimed at setting rates consistent with a recovery, they would need to raise them. We conclude that conventional monetary policy as operated by central banks for the past half-century is fundamentally flawed. Policy-makers had better focus on the quantity variables that cause growth.

Loved reading through it. I always wondered how this all money system is managed and now i feel more worried.

I knew it was very loose and oversight very limited. This a perfect example of how rich become richer and tax payer who are mostly middle class and poor keep in feeding this money making business of banks.

Reserve bank is a mute spectator and if their leader is not very intelligent, it results in more easy money for the ones born with a silver spoon.

God save the middle class and poor. I don't see any hope unless you marry a daughter of a bank owner. 😁😁😁😁

I don't see any hope unless you marry a daughter of a bank owner

How about being born middle class, and and becoming "rich" (to use your word), on your own accord, by working smart and hard?

Yvil,

"on your own accord, by working smart and hard?"

I know i shouldn't but this sort of self-serving crap just makes me angry. If you are lucky enough to be born 'middle class'-as I was, then you immediately get some of life's privileges-a decent warm home, enough food, clothes, money, education to give you a start in life that so many just don't get.

Working hard and smart is good- I am sure that's what you did and Idid too-retired at 57- but unlike smug little you, I am well aware of the part luck has played in my life.

Capital: if borrowers are unable to repay their loans, banks’ shareholders lose money. Banks need to have enough shareholders’ equity to absorb potential losses and avoid the bank becoming insolvent.

Hmmmmm...

Bank shareholder returns on regulatory bank capital required to lend against land and the improvements built on it are higher.

As a result of a combination of the “risk-weighted assets” system and the credit crisis, banks have basically withdrawn from the thing they were set up to do: facilitate commerce.

For the big four banks, only 16 per cent, on average, of a real estate mortgage is counted when measuring the bank’s capital ratio. This is rising to 25 per cent next year.

But every dollar of an unsecured personal and business loans counts against capital and in some cases the risk weighting is 150 per cent.

Capital — that is, the bank owners’ money — has to be 8 per cent of assets, although mostly it’s around 10 per cent. That is, the ratio of owners money to other peoples’ money has to be no greater than 12.5 to 1 and is usually 10 to 1. The result is that for every dollar of capital, the big four banks can choose to lend $62.50 secured against real estate or $10 unsecured.

Guess what happens? It’s only natural and totally understandable. It’s true that interest rates on personal and business loans can be three times what the banks make on residential mortgages, but that still doesn’t make up the revenue. Link

According to the Reserve Bank, the new capital requirements mean banks will need to contribute $12 of their shareholders' money for every $100 of lending up from $8 now, with depositors and creditors providing the rest.

Banks should be forced to share their profits equitably with depositors and creditors, since all three parties underwrite lending.

Corporate Finance 101 AA - equity is the first loss piece which means it is riskier ergo higher returns. If a depositer wants the higher returns and share price volatility then break the deposit and buy the shares.

More capital is a less painful way to fix the banks

A gradual rise in capital requirements need not suppress earnings, writes Alan Greenspan

So essentially FLP and LSAP drove money into the banks and no one asked whether this money was then used to push up asset prices in a search for yield?

The process has been explained here, yet no central bank seems to have concluded that the money will not find its way down to the peasants. Banks are in the business of purchasing securities, so they used that money to facilitate ever increasing asset prices with low interest, high principle loans. Not productive business development.

Implicitly, these programs were used to push interest rates down, to support the banks making enormous profits off driving up the price of property rights (an unproductive asset). Now that the tap is switching off, the funds will dry up, the banks will decrease lending and recover their funds from the mortgagees who are more or less bound to negative equity.

For a concise, friendly description of the money creation process, the consequences of these policy toolkits are not explored.

As I've previously suggested, there is a strong case for mandating non recourse mortgage loans in NZ. If the banks have their own skin in the game they will be much more careful about the investment quality of both assets & borrowers. It would also tend to encourage investment in productive enterprises.

Theres many reasons why USA average house prices are half NZ, that's one.

Median salary in the USA is now $36K apparently so house prices need to be half of New Zealand. Shame about places over there that people actually want to live in like California where a million dollar house is pretty normal. Houses are cheap for reason, typically they are in places you do not want to live and there are plenty of those in New Zealand.

... house prices are quite high in Darfield ... but who in hell would wanna live there ...

These are all things that MMT has been describing for years but orthodox economics has failed to understand. Mainstream economics sees banks as only intermediaries of loanable funds and taxpayers and bondholders as sources of money to finance the government.

The RBNZ does not make it entirely clear here the governments spending increases both base money and broad money and that taxation and borrowing reduces them again and has nothing to do with financing its spending.

To be fair, this is a useful contribution from RBNZ. My main gripe is this sentence:

'banks connect borrowers and savers via the process of bank lending'

This could be read as saying that banks lend out savers' money, which the rest of the article clearly and correctly states is not the case.

More people do need to understand that the reason we all have more money than we did 10 years ago (in real terms) is because households have gone into ever more debt as we chase the dream of a weatherboard castle. The trouble is that the money that gets injected into the economy by banks eager to help us bid up the price of houses is channeled with ruthless efficiency into the bank and term deposits of the wealthiest few per cent of NZ'ers. This means that when households stop borrowing (like they have now), money stops flowing around the economy, and we have a catastrophic collapse like the one that is coming this year (unless Govt decides to do another big stimulus package, which seems unlikely).

Jfoe, I like your insightful and knowledge comments. Would you mind sharing what you studied and what you do for a living? Thanks

Engineering, science, started out in water treatment plants doing modeling (of literal flows of sh*t), but that was a long, long, time ago. Done generic leadership roles for many years now. Looking forward to retirement to carry on learning macro econ!

Great article, I think I have more questions now than before reading this.

I'd like to see a similar article explaining,during a sharp recession, what banks do when lending defaults increase, customer lending applications fall and loan applicants don't meet the eligible criteria (eg business is struggling).

I guess they just switch to govt bonds until cash gets cheap but I'm not sure.

So an article that explains the period between a sharp crash and the beginning of rate drops

If banks regulatory capital starts to fall below minimum threshold step one is to cancel dividends, step two is to issue more equity, step three is to convert hybrid notes to equity, step four is bail in/ Govt support and our trade sale. I prob left a few things out but thats pretty much how things go down when loan losses start to eat into equity.

OBR - Open Bank Resolution

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/regulation-and-supervision/oversight-of-banks/….

Kinda long so will need to read more carefully later.

But I didn't see any time series info of M2/broad money increase over time. Is it average of 6% per year pre COVID, and how much per year post covid? Is that enough, too much?

How much will that affect inflation? Is it fair to say that some new NZD gets stuck in assets and overseas issued bonds but eventually will flow through to NZ inflation?

Thanks interest.co - great read. Will read again tomorrow as well.

Took the L route through high school. Should have taken the C route.

Sounds like you're taking the C route now, WJ, good on you, it's never too late!

The Reserve Bank is responsible for maintaining people’s trust in money.

From what I could see during the pandemic it took relatively little to convince people that, pragmatically, toilet roles where better than money. Yet we failed to appreciate this was actually an early sign of runaway inflation as people lost a small amount of trust in our economic system that substantially changed their behaviour with regards to spending and consequently inflation.

The more I think and read about money the more I've come to realise that we do not have a complete enough picture to produce meaningful forecasts.

What ever it is …. Reserve bank have no right to seize money from working class by playing with ocr in the name of inflation

or else reserve should make it clear if it is a profit seeking company or it is a non profit organisation

if the purpose of ocr is not profit , the amount equivalent to OCR collected can pay the principal amount of borrower which can stil reduce spending.

The Reserve Bank is not a profit making organisation and interest payments go to the commercial banks not the RBNZ. Higher interest rates actually cost the government more in the interest payments on its reserves.

Nice article. Thanks.

These people like to make the banking system sound complicated so that we don’t discover how it actually works. Here’s the magic trick: The commercial banks create money when a loan is taken out, and that money is destroyed when the loan is payed back.

Like any good Ponzi scheme, the monetary system requires more debt/credit to keep it going, otherwise the house of cards comes crashing down.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.