By David Skilling*

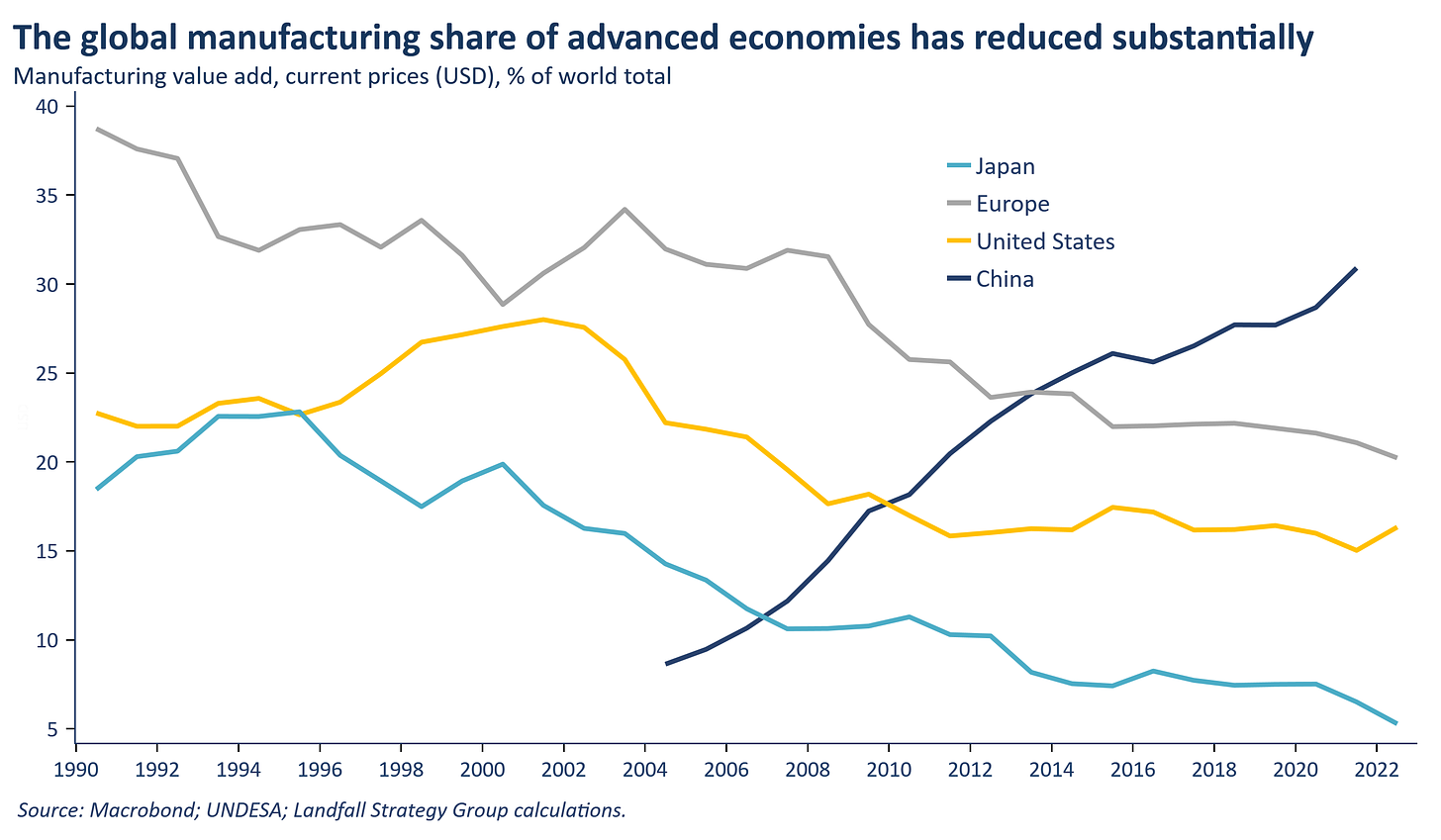

Over the past few decades, the manufacturing shares of GDP across advanced economies have reduced markedly. Manufacturing activity has relocated to China and elsewhere, leading to a rotation in the shares of world manufacturing. China has become the world’s largest manufacturer, and by a substantial margin.

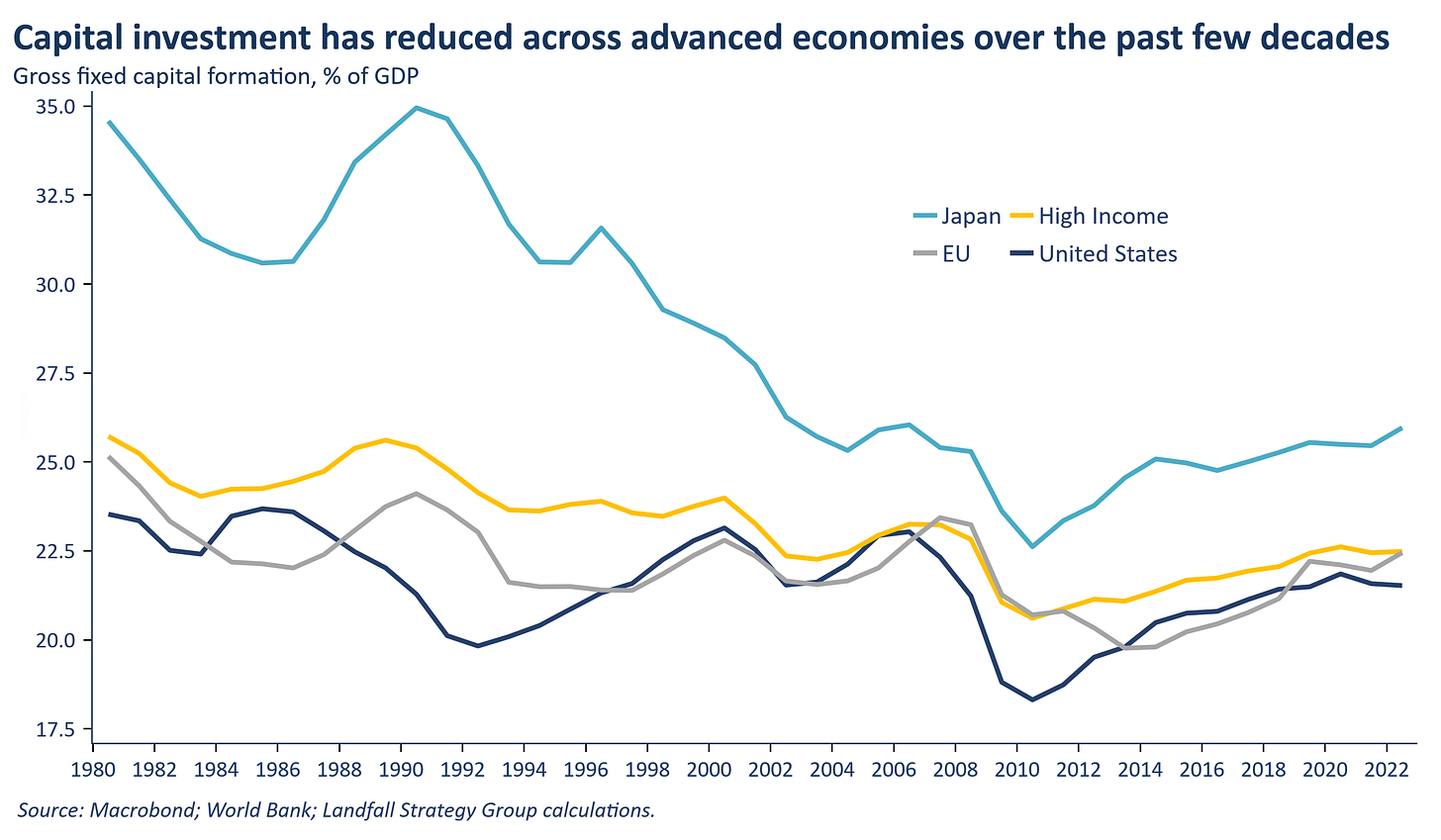

Relatedly, gross (and net) investment shares of GDP have reduced across advanced economies over the past few decades – and reduced further since the global financial crisis despite low/negative interest rates. From infrastructure to business capex, private and public sector investment has been muted across advanced economies – with some capital intensive activity migrating to economies like China.

These weakening levels of investment are an important reason for weak productivity performance across advanced economies over the past few decades; coinciding with sector shifts into lower productivity services activity. Lower levels of capital intensity have dragged on advanced economy productivity.

The capex boom

But looking forward, a surge in investment across advanced economies is gathering strength – ‘the great reindustrialisation’. This advanced economy reindustrialisation process will run in parallel with ongoing heavy investment in China and elsewhere. This capex boom will have first-order implications across the global economy.

This reindustrialisation process will be driven by significant capital investment in areas such as the net zero transition and disruptive technologies like AI, reinforced by the strategic imperatives associated with geopolitical rivalry: wartime economies tend to be capital intensive.

There is substantial investment that will be required in the green transition; renewable energy generation, the electricity grid, as well as hydrogen, nuclear, and so on. The OECD estimate that capital investment of >2.5% of GDP across advanced economies is required by 2030 to deliver net zero by 2050, up from investment of 1% of GDP over 2017-2021. In Europe alone, estimates of required green investment run to €500 billion.

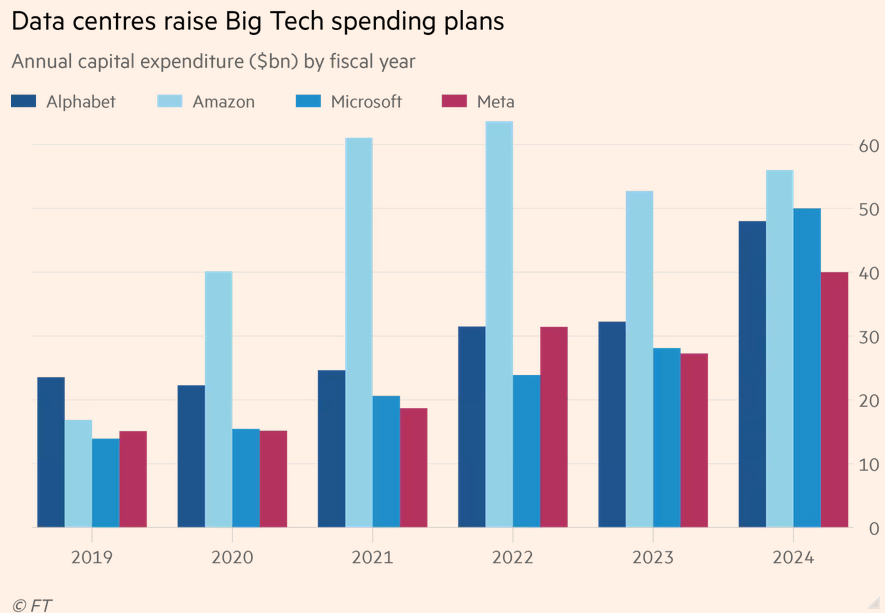

In the technology space, there are eye-watering estimates of the capex required to produce the semiconductors and computing power required to train and deploy AI (as well as to generate the massive amounts of energy required to run these facilities). A recent study estimated that semiconductor production would triple in the US by 2023, with significant increases also in Europe, Japan and elsewhere. The increase in technology capex (see chart below) is a reason that the share prices of firms such as ASML, TSMC, and Nvidia have gone exponential.

Beyond AI, substantial capital investment is also expected in areas such as quantum, fusion, life sciences, and much else.

Governments are getting heavily involved in directly funding this capex or subsidising private sector firms to invest. This is partly to capture economic value from the new commanding heights of the global economy; and because these investments are a core part of the full-spectrum strategic competition between geopolitical rivals.

Aggressive industrial policy support has become mainstream in large economies, from the US and Europe to China and Japan. In the US, legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS & Science Act have directed hundreds of billions of dollars towards investment in the US; including encouraging foreign firms like TSMC to invest in the US. Taken together, these US industrial policy initiatives are larger than the post-War Marshall Plan as a share of GDP.

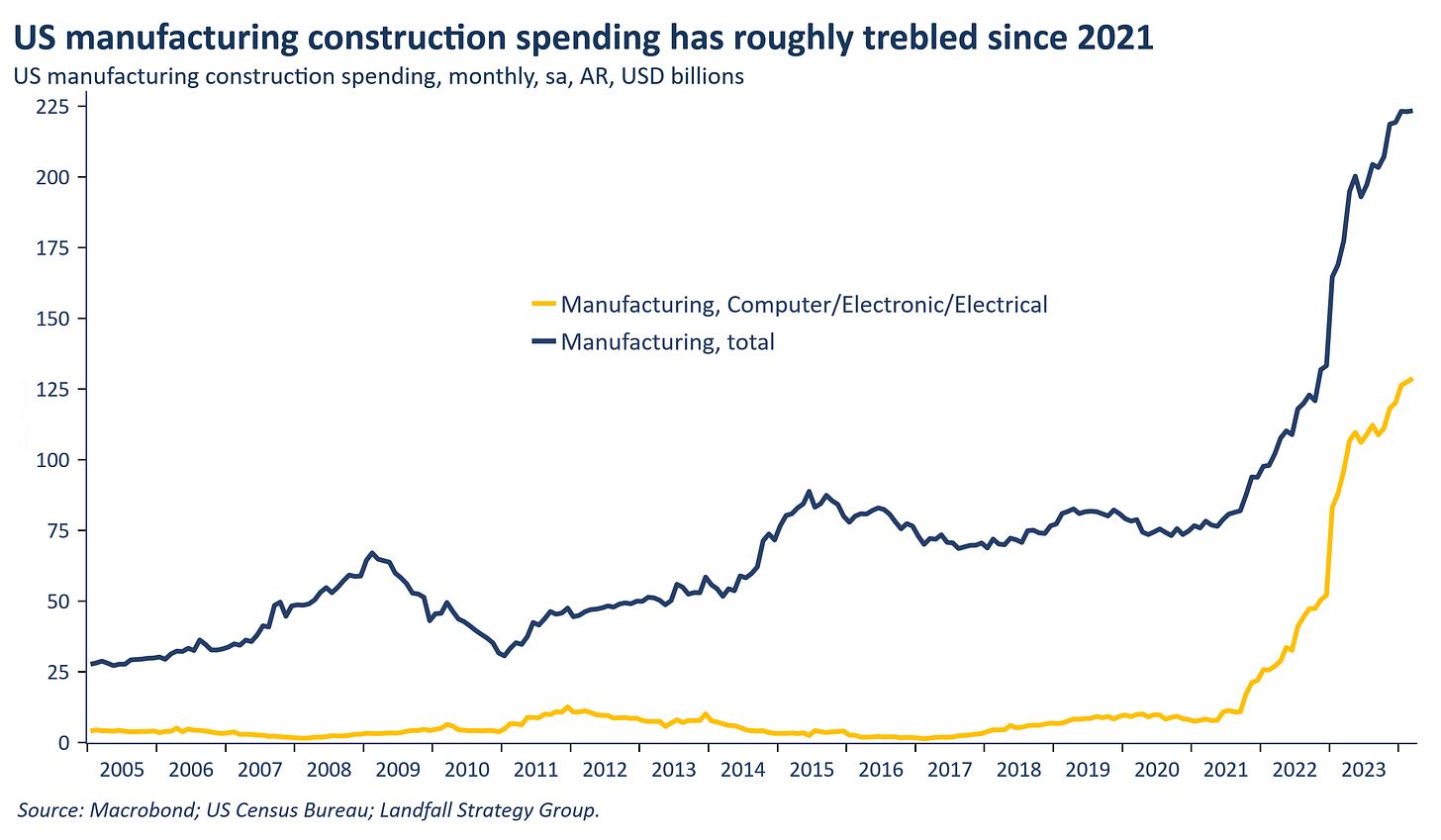

As one marker of the scale of this investment, US factory capex has increasing very rapidly over the past few years, driven by IT-related sectors.

Similar (but smaller) industrial initiatives are being rolled out in Europe, both at EU level as well as by individual countries; Germany is spending tens of billions to incentivise semiconductor and battery production. And China is supporting industrial activity. A recent estimate noted that $380 billion of government support had been committed globally to semiconductor production (~0.4% of global GDP), of which ~$80 billion has been spent.

Beyond this, geopolitical rivalry is leading to increased military spending. Last year was a record in terms of worldwide military spending, and this will increase. Across NATO, 2% of GDP is becoming a floor for military spending – with many spending more, including on military-related capex.

Full spectrum strategic competition between geopolitical rivals is leading to increased investment in advanced economies as global supply chains are rewired. Firms are being required or incentivised to de-risk/decouple from geopolitical rivals and locate production of strategically sensitive goods at home or in friendly markets (such as India, Vietnam, and Mexico). In many instances, this will result in additional capital investment as new production facilities are constructed.

This is being reinforced by investments to strengthen the resilience of global supply chains: less focus on offshoring production to lower cost locations, and more investment being made in advanced economies.

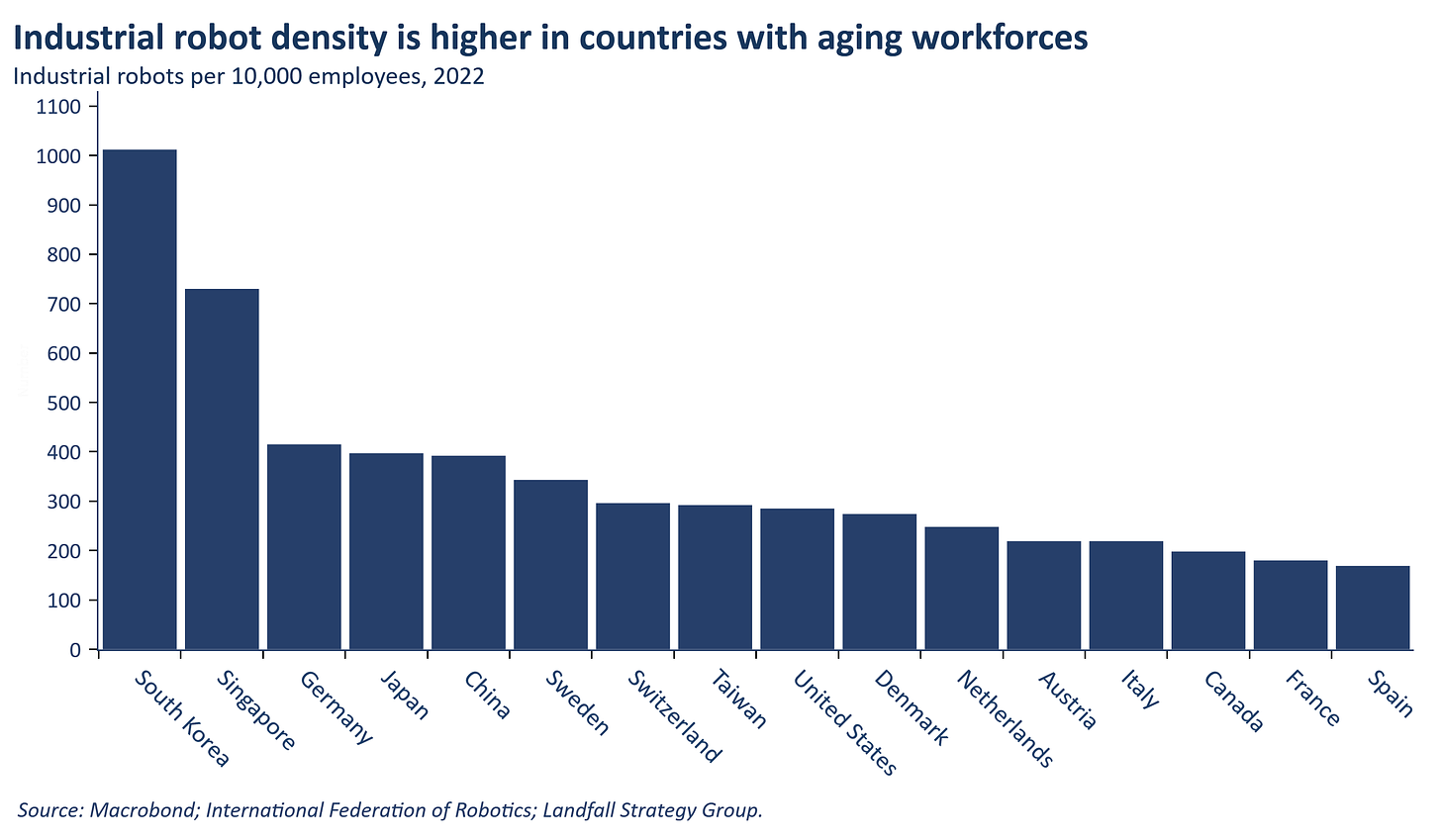

Additional capital investment is also being induced by population aging; as working age populations contract in some advanced economies, capital and technology will be deployed. Indeed, industrial automation density is higher in countries with challenging demographics, such as Japan and South Korea.

Taken together, public and private sector investment is likely to expand substantially over the next decade and beyond – and to a greater extent that is factored into many forecasts at the moment. Higher interest rates will not meaningfully deter these higher investment rates, just as low interest rates did not stimulate productive investment after the global financial crisis.

It’s a material world

Increased capex will lead to stronger GDP growth, as well as higher inflation and rates (as stronger demand interacts with more supply side frictions across the global economy). Strong economic contributions from investment has characterised previous periods of strategic competition.

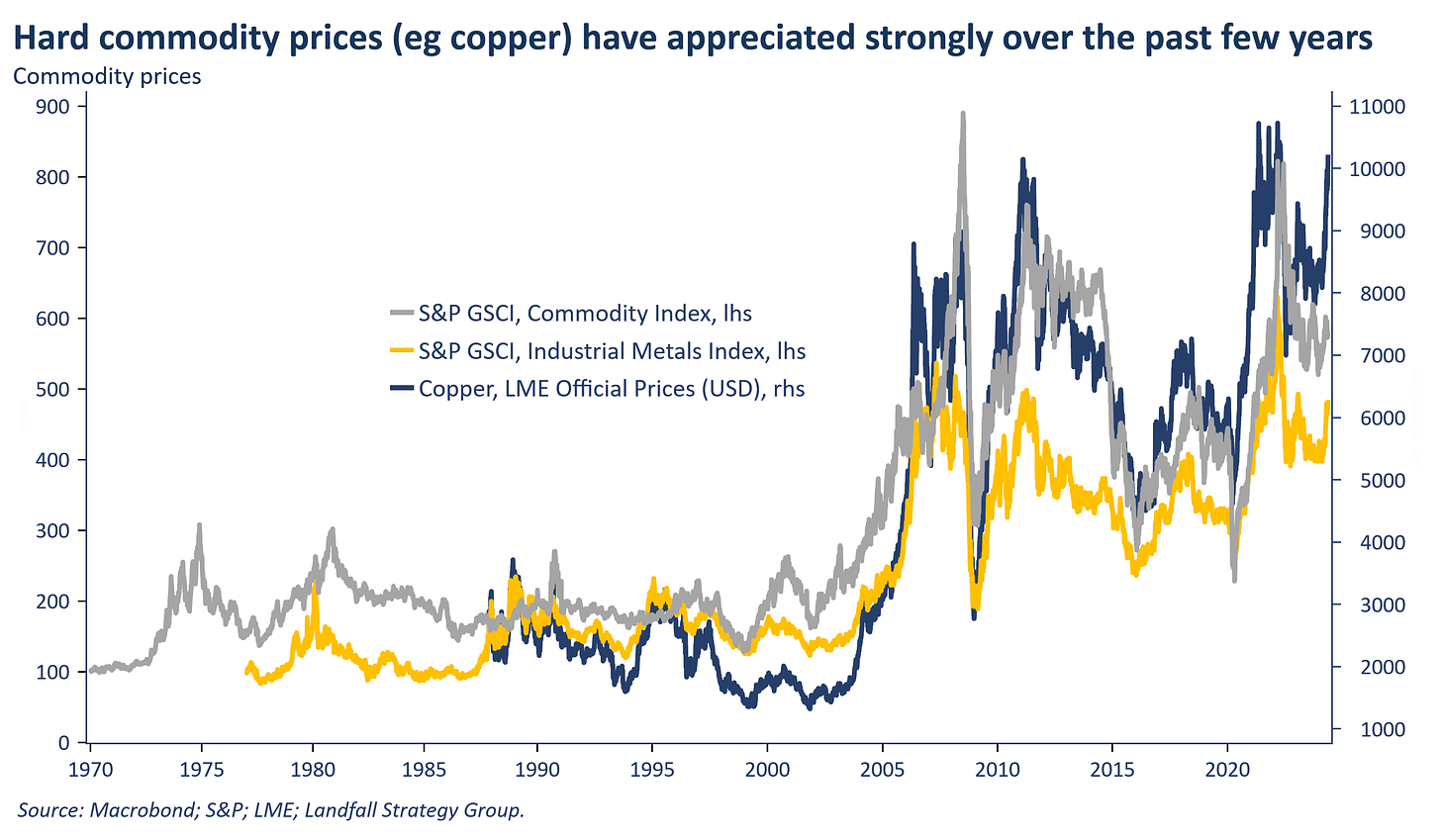

Although much investment in innovation is weightless/intangible (AI, biotech, quantum), the supporting infrastructure is often heavy – energy, data centres, factories. This means increased demand for commodities that are inputs into construction, technology, and the net zero transition. From uranium to copper, a range of commodities have moved sharply higher over the past several months on higher expected demand (as well as some speculative buying). Copper prices are up ~25% since January.

There has been under-investment in commodity supply relative to this expanding commodity demand, and higher prices are needed to incentivise additional investment in supply. Strong Chinese growth led to a commodity price boom two decades ago; and echoes of this are likely over the next decade and beyond.

These dynamics will also lead to higher levels of government debt as governments seek to finance a broad range of strategic priorities. Economic war is not cheap. This will put pressure on macro policy institutions. Expect new approaches to government balance sheet management: through history, those states that were best able to mobilise capital had a competitive edge. Countries will also need well-performing capital markets to mobilise private capital: the US has a pronounced edge here.

Lastly, this investment surge is likely to be positive for productivity. Although some investment will not contribute directly to productive potential (weapons systems) and some will be inefficient (redundant investment because of global economic fragmentation), increased investment in technology, infrastructure, and automation will push out the supply side of the economy – and will likely raise trend productivity growth.

Overall, strategic competition between geopolitical rivals, combined with technology, demographic, and climate dynamics, will lead to a surge in capex over the next decade and beyond. This great reindustrialisation in advanced economies (and elsewhere) will support different economic dynamics than over the past 15 years: higher growth, higher inflation, higher rates, higher debt, and some support for increased productivity growth. And there will be winners and losers from reindustrialisation at national, sector, and firm levels.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

13 Comments

There is great wealthto be gained from shifting back to being 'makers'.

We are discovering the over educated law and accounting types in highrise offices do not create wealth.

You know: Those images of five good looking people with laptops around a conference table getting really excited about the PowerPoint presentation. Time to backpedal on that.

Valuing ownership again would help too.

There is great wealthto be gained from shifting back to being 'makers'.

The Anglosphere in particular has ridiculed Japan for its economic 'failure', yet to be frank, the rise of China and Asia in terms of production and development stems from Japan's know-how. Ask anyone at the water cooler who Olympus as a company is and they will probably say something like a failed camera maker. Not a leader in endoscopic (70% market share), ultrasound, electrocautery, endotherapy, and cleaning and disinfection equipment.

Or we can just count the toyotas everywhere

Most Toyotas are not manufactured in Japan.

That's a result of Japan's rapidly shrinking technical workforce. Engineering talent in Japan is becoming a scarce resource and companies such as Toyota get much better value by utilising Japanese workers in design or premium car manufacturing. Case in point, most cars under Toyota's premium brand Lexus are manufactured in Japan.

Indeed, industrial automation density is higher in countries with challenging demographics, such as Japan and South Korea.

Is this a coincidence?

"East Asia democracies" is a euphemism for US-occupied client regimes. Actual democracy is a process of self-determination, everything in Japan, South Korea & on the island province of Taiwan is determined by/for Washington. Link

Quote Glinert @StevenGlinert ·May 16

Singapore has basically transitioned to fully democratic at this point. Lee Kwan Yew being alive/in power was an impediment, but with the end of the Lee dynasty ruling the country, I think Singapore has really joined the league of East Asian democracies like Kor, Jap, Tw. x.com/LawrenceWongST…

Everything determined by/for Washington - I doubt that applies to Washington DC let alone Japan.

Better expressed as actions that are somewhat constrained by a bigger bullying country. Such as banning nuclear vessels in territorial waters. Or welcoming a religious leader such as the Dalai Lama or the Pope. Is NZ a UK, US or Chinese client regime?

Japan, South Korea and Singapore have US military bases inside their borders, while Taiwan has US military personnel stationed on its islands in the Taiwan Strait.

You make a good point. But not if over-emphasized. The UK houses US military bases. I realise Uk politicians are rubbish and untrust worthy and admiring of the USA and believing in 'a special relationship' but the UK is not a client state. They do things the USA don't like - no UK army in Vietnam.

Even the British Empire had to deal with dissatisfaction and willfulness in various parts of its global holdings. Doesn't mean that Great Britain didn't get 95% of its way 95% of the time.

They do things the USA don't like And what they might like.

You know, the silver lining in the useless war in Ukraine is that the UK is willingly disarming itself. Now, if Powell and Co. at the M-E Building does the same to City of London, we can finally be rid of these ..... Link

Chinas industrial policy has two arms, the first is holding the value of the Chinese Yuan low they keep labour costs low and the second is that they effectively subsidise son industries with state capital.

The benefit for Western countries is that the enjoy very low CPI by importing cheap goods and abundant low cost credit because the Chinese keep buying bonds. Unfortunately, rather than leaning into this to borrow/invest and offset the impact by increasing pressure capital productivity, we have had an era of extreme austerity. The only place for capital to go has been blowing up asset bubbles.

This will probably be our last change to make China pay for its industrial policy because internal factors within China mean this model is doomed.

This reindustrialisation process will be driven by significant capital investment in areas such as the net zero transition and disruptive technologies like AI...As one marker of the scale of this investment, US factory capex has increasing very rapidly over the past few years, driven by IT-related sectors.

A bug chunk of that spending is going on foreign made technology and machines eg. those made by Dutch company ASML and as already noted by the writer, foreign based fabs like TSMC. In effect, a lot of that spend isn't re-industrialising the United States at all, it is supporting foreign technology and foreign manufacturing.

Further, capex expenditure on a high tech factory like a brand new chip fab this year may not actually mean any production for five or more years. And it takes even longer than that to train a workforce and develop a quality subcontractor base capable of supporting that chip fab.

In summary western analysts keep making the same mistakes in this area, including assuming that financial metrics like GDP or capex directly translates into actual industrial capability and industrial capacity. It might do over time, but many of these high tech projects end up being failures (just ask Intel which spent billions on manufacturing technologies which simply failed to be competitive.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.