By Bo Li and Nobuyasu Sugimoto

The already volatile world of crypto has been upended anew by the collapse of one its largest platforms, which highlighted risks from crypto assets that lack basic protections.

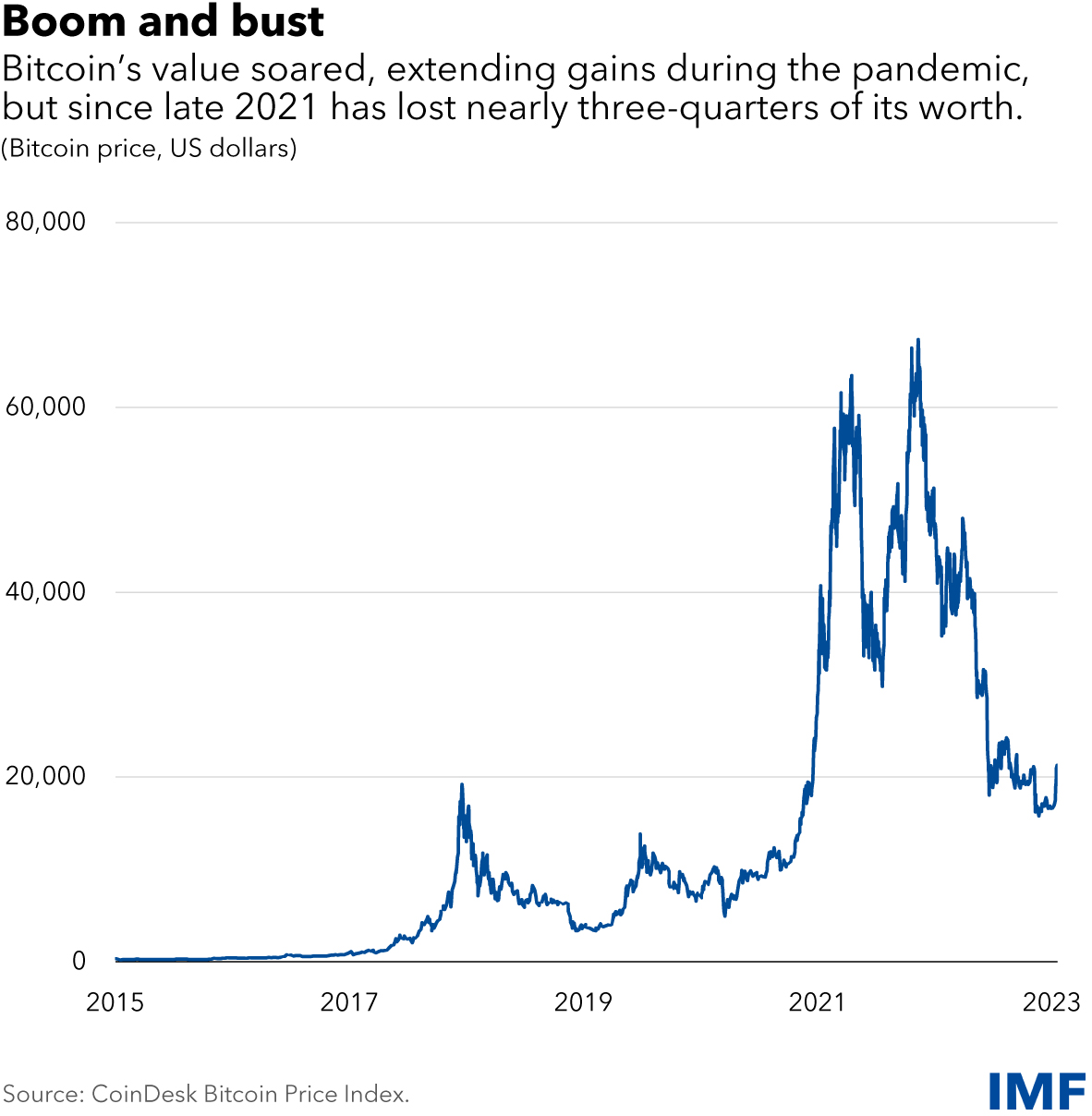

The losses punctuated an already perilous period for crypto, which has lost trillions of dollars in market value. Bitcoin, the largest, is down by almost two-thirds from its peak in late 2021, and about three-quarters of investors have lost money on it, a new analysis by the Bank for International Settlements showed in November.

During times of stress, we’ve seen market failures of stablecoins, crypto-focused hedge funds, and crypto exchanges, which in turn raised serious concerns about market integrity and user protection. And with growing and deeper links with the core financial system, there could also be concerns about systemic risk and financial stability in the near future.

Many of these concerns can be addressed by strengthening financial regulation and supervision, and by developing global standards that can be implemented consistently by national regulatory authorities.

Two recent IMF reports on regulating the crypto ecosystem are especially timely amid the severe turmoil and disruption in many parts of the crypto market and the repeated cycles of boom and bust for the ecosystem around such digital assets.

Our reports address the issues noted above at two levels. First, we take a broad approach, looking across key entities that carry out the core functions within the sector, and hence, our conclusions and recommendations apply to the entire crypto asset ecosystem.

Second, we focus more narrowly on stablecoins and their arrangements. These are crypto assets that aim to maintain a stable value relative to a specified asset or a pool of assets.

New challenges

Crypto assets, including stablecoins, are not yet risks to the global financial system, but some emerging market and developing economies are already materially affected. Some of these countries are seeing large retail holdings of, and currency substitution through, crypto assets, primarily dollar-denominated stablecoins. Some are experiencing cryptoization—when these assets are substituted for domestic currency and assets, and circumvent exchange and capital control restrictions.

Such substitution has the potential to cause capital outflows, a loss of monetary sovereignty, and threats to financial stability, creating new challenges for policy makers. Authorities need to address the root causes of cryptoisation, by improving trust in their domestic economic policies, currencies, and banking systems.

Advanced economies are also susceptible to financial stability risks from crypto, given that institutional investors have increased stablecoin holdings, attracted by higher rates of return in the previously low interest rate environment. Therefore, we think it’s important for regulatory authorities to quickly manage risks from crypto, while not stifling innovation.

Specifically, we make five key recommendations in two Fintech Notes, Regulating the Crypto Ecosystem: The Case of Unbacked Crypto Assets and Regulating the Crypto Ecosystem: The Case of Stablecoins and Arrangements, both published in September.

1. Crypto asset service providers should be licensed, registered, and authorized. That includes those providing storage, transfer, exchange, settlement, and custody services, with rules like those governing providers of services in the traditional financial sector. It’s particularly important that customer assets are segregated from the firm’s own assets and ring-fenced from other functions. Licensing and authorization criteria should be well defined, and responsible authorities clearly designated.

2. Entities carrying out multiple functions should be subject to additional prudential requirements. In cases where carrying out multiple functions might generate conflicts of interest, authorities should consider whether entities should be prohibited to do so. Where firms are permitted to, and do carry out multiple functions, they should be subject to robust transparency and disclosure requirements so authorities can identify key dependencies.

3. Stablecoin issuers should be subject to strict prudential requirements. Some of these instruments are starting to find acceptance beyond crypto users, and are being used as a store of value. If not properly regulated, stablecoins could undermine monetary and financial stability. Depending on the model and size of the stablecoin arrangement, strong, bank-type regulation might be needed.

4. There should be clear requirements on regulated financial institutions, concerning their exposure to, and engagement with, crypto. If they provide custody services, requirements should be clarified to address the risks arising from those functions. The recent standard by Basel Committee on Banking Supervision on the prudential treatment of banks’ crypto assets exposures recently is very welcome in this respect.

5. Eventually, we need robust, comprehensive, globally consistent crypto regulation and supervision. The cross-sector and cross-border nature of crypto limits the effectiveness of uncoordinated national approaches. For a global approach to work, it must also be able to adapt to a changing landscape and risk outlook.

Containing user risks will be difficult for authorities around the world given the rapid evolution in crypto, and some countries are taking even more drastic steps. For example, sub-Saharan Africa, the smallest but fastest growing region for crypto trading, nearly a fifth countries have enacted bans of some kind to help reduce risk.

While broad bans might be disproportionate, we believe targeted restrictions offer better policy outcomes provided there is sufficient regulatory capacity. For instance, we can restrict the use of some crypto derivatives, as shown by Japan and the United Kingdom. We can also restrict crypto promotions, as Spain and Singapore have.

Still, while developing global standards takes time, the Financial Stability Board has done excellent work by providing recommendations for crypto assets and stablecoins. Our Fintech Notes draw many of the same conclusions, a testament to our close collaboration and shared observations on the market. For its part, the IMF will continue to work with global bodies and member nations to help leading policy makers working on this topic to best serve individual users as well as the global financial system.

Bo Li is a Deputy Managing Director at the IMF. Nobuyasu Sugimoto is a Deputy Division Chief of Financial Supervision and Regulation Division, Monetary & Capital Markets Department of the IMF. This article reflects research contributions by Parma Bains, Fabiana Melo, and Arif Ismail This is a re-post of an article that ran on the IMF blog.

18 Comments

If you don't like the libertarian nature of cryptocurrency, don't get involved in it. I, however, do like that and I think that greater regulation will have negative unintended side-effects.

A currency that starts with the founder retaining a large percentage of the currency isn't really libertarian. It's more like a religion with the promise of being one of the souls that gets to heaven if they believe enough.

Man crypto can't catch a break on interest.co at the moment.

.. at least when the tulipmania bubble burst 400 years ago in the Netherlands , you were left with something you could eat ...

What currency are you referring to here? Can't be Bitcoin...

Cryptocurrency is hardly libertarian. With the large exchanges setup to provide transaction services and trading it is more and more like the existing system we already had just using 1000x more energy and without any of the protections from fraud and market manipulation. A capitalist dream of being able to restrict access, & control through large holdings enabling a greater share of influence over the movements and a willing public sitting eagerly by their sponsored social media ready to believe anything posted to drive them this way and that. The fact so many exchanges have been shown to not even have the basic protections of having security or money in trust or backed in any way, and no recourse for customers when the exchange is shown to be flawed legally really does mean it is the best thing for those who had been having wet dreams of market manipulation scams but did not want to be caught out. A libertarian would look at the existing system heavily dominated by a few global players and increasingly susceptible to corruption and harm towards millions of customers who had little real choice in the market and wonder where it all went wrong. A smart ethical libertarian would run screaming from it.

Consider non-custodial exchanges. Anyone with two sticks to rub together can see which makes more sense.

Why is the answer always more regulation, more supervision, more interference.

If the definition of fascism is private ownership with central government total control then we are careening toward that at a great pace.

Er no that is not the definition or even the right terms to use. You seem to think that consumer protections and preventing insider trading and monetary fraud are bad things. What to instead stand on the right and factual side of history, the one without the conspiracy theorists and pyramid scheme gurus.

IMF: “Monetary policy would lose bite. Central banks cannot set interest rates on a foreign currency. Usually, when a country adopts a foreign currency as its own, it “imports” the credibility of the foreign monetary policy and hope to bring its economy–and interest rates–in line with the foreign business cycle. Neither of these is possible in the case of widespread cryptoasset adoption.”

Bingo. Bitcoin gives citizens the ability to choose a monetary system without devaluation.

The IMF talks about stopping financial crime and how Bitcoin will make its job tougher. In reality, these institutions protect the corrupt elite while advancing an increasingly aggressive financial surveillance state on citizens globally.

Russian gets arrested by FBI only days ago for dodgy Crypto practices.

https://edition.cnn.com/2023/01/18/business/crypto-arrest/index.html#:~….

Yet Congress and the SEC hobnob with SBF.

Seems a dumb idea as with regulation comes legitimacy. Would we have wanted regulatory authorities to have to bail out FTX?

No thanks. Best left in its wild west form, I think.

Seems a dumb idea as with regulation comes legitimacy. Would we have wanted regulatory authorities to have to bail out FTX?

FTX Japan didn't need to be bailed out. All assets needed to be backed 1:1 under Japan FSA regns.

Interesting point - backed by what? But, wouldn't the market completely collapse if that kind of regulatory requirement had to be met universally.

1. The FSA requires Japanese exchanges to keep at least 95% of customers' crypto in cold wallets. Because cold wallets are not connected to the internet, they are more secure against hacking and internal fraudsters. For the 5% of customer's crypto that can be kept in a less-secure hot [internet connected] wallet, Japanese exchanges must back each unit of hot-walleted crypto with exchange-owned crypto held in a segregated cold wallet. So, for example, if an exchange holds 5 BTC of customer funds in a hot wallet, it must hold another 5 BTC of its own personal coins in reserve, for a total of 10 BTC.

2. Japanese crypto exchanges must segregate customer fiat and crypto from the exchange's own crypto. That is, they can't deposit the exchange's own operating funds into the same account, or wallet, as their customers' funds.

3. Japanese exchanges must entrust customers' fiat money balances to a third-party Japanese institution – a trust company or bank trust – where they are managed by a trustee with customers designated as the beneficiaries.

4. A more explicit bankruptcy protection stipulates that customers of Japanese exchanges are entitled to receive payment in priority to general creditors in the case of bankruptcy.

There are no requirements for bailing out a failing investment company from it's own illegal practices, poor management and fraud. There is no bailing out of most failed investment companies. Legitimacy would instead mean less people are victim to such corrupt and inept practices though a basic set of laws and standards. Such as don't claim it is an investment exchange taking peoples money then having a big throw around fraud party in the background, leaving it open to illegal theft, skimming and using it to shore up personal interests. Simple stuff.

Just pointing out that this is the equivalent of asking someone who is paid a large salary by Blockbuster, for their opinion on regulating Netflix...

The ruling elite have mainly benefitted from the scams. Not ol' ratty mainly because it represents a threat to their power and control.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.