By Tobias Adrian, Christopher Erceg, Fabio Natalucci

Central banks aggressively hiked interest rates last year as inflation in many countries rose to the highest levels in decades. Now, falling energy prices are reducing headline inflation and fueling optimism that monetary policy may be eased later this year.

Such expectations have caused a sharp decline in global longer-term interest rates and boosted financial markets in advanced economies and emerging markets alike.

Though this may make it tempting to conclude that monetary policy is becoming overly restrictive and poised to cause an unnecessary economic contraction, investors may be too sanguine about progress on disinflation. While headline inflation has indeed fallen, and core inflation has receded slightly in some countries, both remain far too high. Central banks must therefore be resolute in their fight against inflation and ensure policy remains appropriately tight long enough to durably bring inflation back to target.

Aggressive tightening

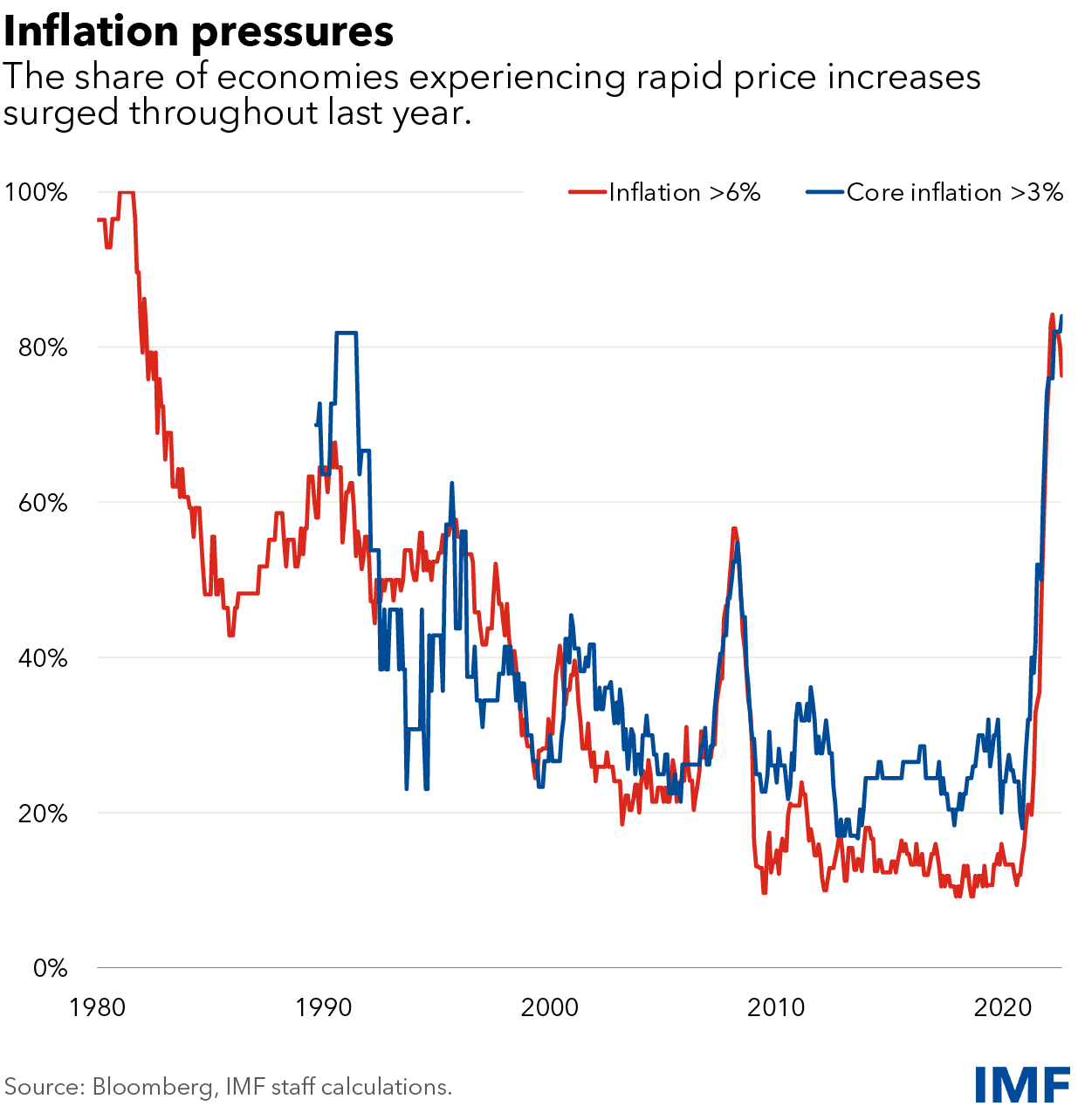

After many years of low inflation, the surge in inflation during the pandemic recovery came as a surprise. Key factors driving inflation included supply disruptions, high energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and massive monetary and fiscal stimulus that fueled spending on housing and durable goods. Inflation topped 6 percent in more than four-fifths of the world’s economies, while increasingly broad-based price gains lifted expectations for further increases to multi-decade highs.

Central banks in emerging markets responded by sharply tightening policy beginning in 2021, followed by their counterparts in advanced economies. This led to a tightening of financial conditions globally through the fall of last year. As a result, global economic growth is now expected to slow this year, with divergent views on the extent to which unemployment would likely need to rise to cool hot labor markets.

Investor optimism

Since late last year, however, financial markets have rebounded strongly on retreating energy prices and signs that inflation may have peaked. In some economies, prices for goods included in core inflation measures, such as autos and furniture, have fallen.

These signs of progress in reducing inflationary pressures amidst continued strength in labor markets have offered reason to believe that policymakers may have succeeded in taming inflation with little cost to economic growth, a so-called soft landing.

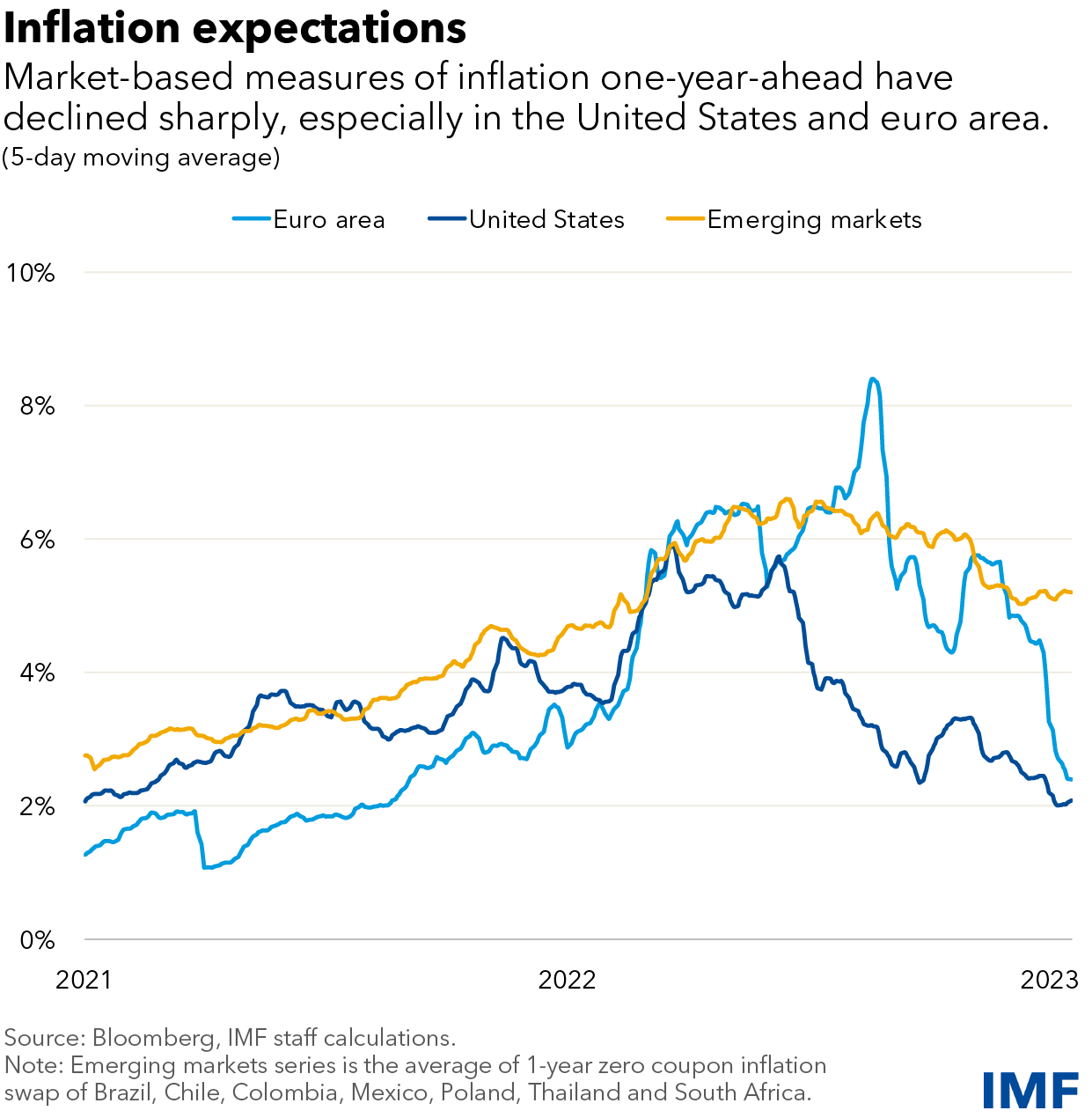

In the United States and the euro area, market-based measures of inflation one year ahead have returned to near the central banks’ 2 percent target from 6 percent last spring. Gauges for several other advanced economies have seen similar drops. In emerging markets, such market-based measures of inflation one year ahead have also been falling, albeit at a slower pace.

Expected easing

These disinflation hopes have been accompanied by growing expectations that central banks will soon not only stop tightening policy but also reduce rates fairly quickly. In many economies, this has led to yields on long-dated government debt falling below short-dated maturities. Historically, such an inversion of the yield curve often precedes recessions. Analyst assessments in fact point to significant recession risk in many economies, but the expectation is that recessions, should they occur, will be mild.

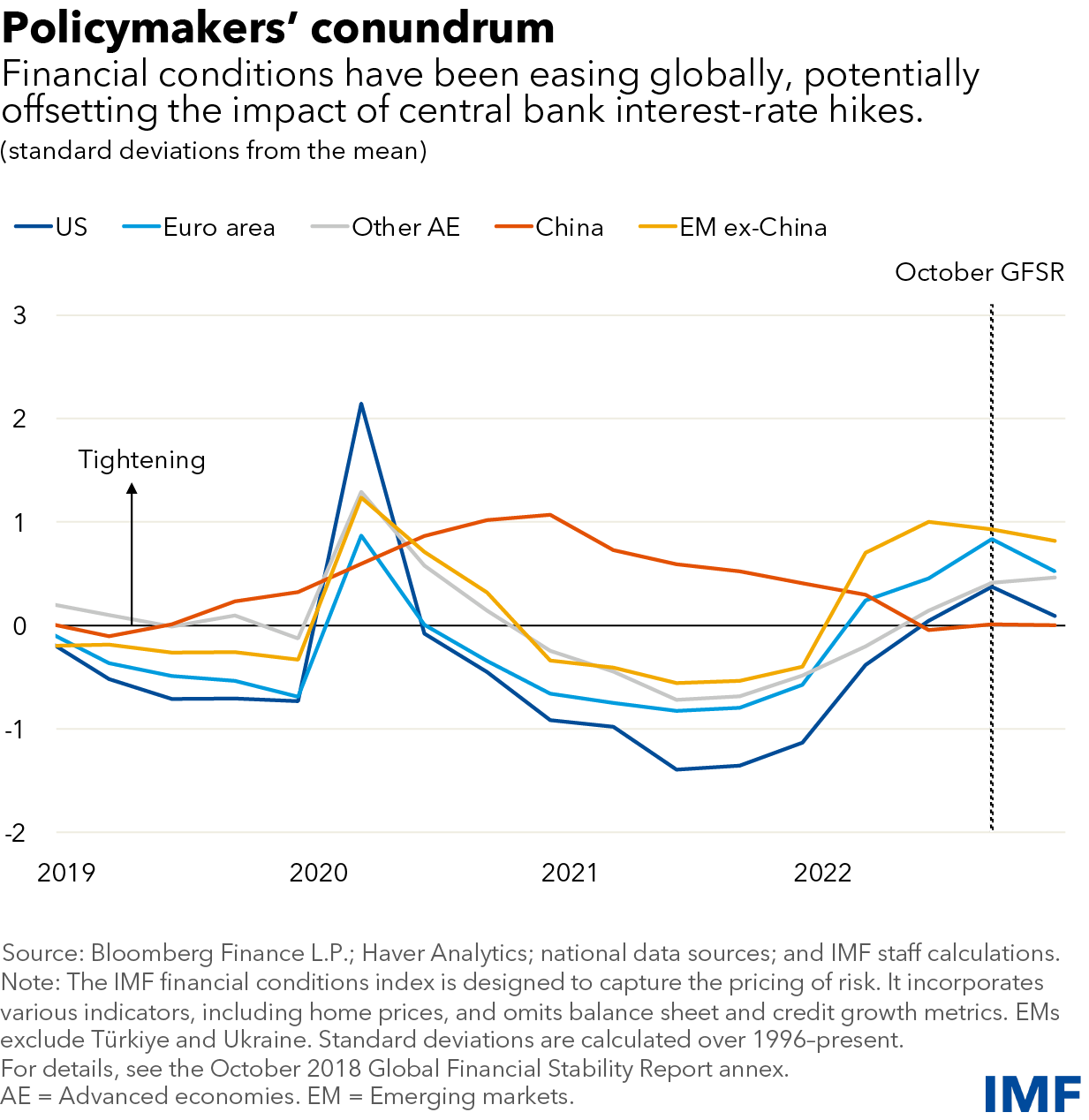

Growing expectations for lower interest rates and only a shallow economic slowdown have fueled a significant easing in financial conditions in recent months—despite central banks continuing to raise rates. Markets have reflected this relatively benign picture: stock markets have rallied, and credit spreads narrowed considerably.

Conundrum for central banks

This easing of financial conditions during a central bank tightening cycle creates a conundrum for policymakers.

On the one hand, financial markets are signaling that disinflation may occur without meaningful increases in unemployment. Policymakers could embrace that view, and in effect ratify the loosening of financial conditions. Many observers concerned that central banks will be overzealous about tightening monetary policy—and will cause an unnecessarily painful economic downturn—are endorsing such a view.

Alternatively, central banks could push back against investor optimism, emphasizing the risks that inflationary pressures may be more persistent than expected. This risk-management approach would require restrictive interest rates for longer, until there’s tangible evidence of a sustained decline in inflation.

While doing so could induce a repricing of the policy path and of risk assets in financial markets—possibly causing equity prices to fall and credit spreads to widen—there are three reasons why such an approach is needed to ensure price stability.

- History shows high inflation is often persistent—and may possibly ratchet up further—without forceful and decisive monetary policy actions to reduce it.

- While goods inflation has come down, it seems unlikely that the same will happen for services without significant labor-market cooling. Crucially, central banks must avoid misreading sharp declines in goods prices and easing policy before services inflation and wages, which adjust more slowly, have also moderated markedly.

- Experience suggests that prolonged periods of rapid price gains make inflation expectations more susceptible to de-anchoring as such an inflationary mindset becomes more entrenched in the behavior of households and firms.

Policymakers must continue to be resolute

Central banks should communicate the likely need to keep interest rates higher for longer until there is evidence that inflation—including wages and prices of services—has sustainably returned to the target.

Policymakers will likely face pressure to ease policy as unemployment rises and inflation keeps falling. These challenges could be particularly acute for emerging market economies.

To be sure, this is an unusual period in which many special factors are affecting inflation, and it is possible that inflation comes down more quickly than policymakers envision. However, loosening prematurely could risk a sharp resurgence in inflation once activity rebounds, leaving countries susceptible to further shocks which could de-anchor inflation expectations. Hence, it is critical for policymakers to remain resolute and focus on bringing inflation back to target without delay.

Tobias Adrian is the Director of the IMF's Monetary and Capital Markets Department. Christopher Erceg is deputy director in the Monetary and Capital Markets Department. Fabio Natalucci is a Deputy Director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department. This is a re-post of an article that ran on the IMF blog.

3 Comments

Can't people get paid to write this stuff.

... why , can't they ? ...

"History shows high inflation is often persistent—and may possibly ratchet up further—without forceful and decisive monetary policy actions to reduce it."

Last time we had a spike of high inflation in NZ, it took several years before it got back under control.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.