When US President Donald Trump says he will increase tariffs on imports to America, most people think of physical goods first and foremost.

For example, in response to Trump, Canada will apply 25 per cent tariffs (or customs duties) on US beer, wine, spirits, fruits and juices, certain consumer goods and household appliances. Possibly to the chagrin of Elon Musk, Tesla electric vehicles will also be hit with a 25 per cent tariff.

This will put up prices and no doubt dampen demand for Teslas in Canada. It would’ve made Chinese EVs more competitive had Canada not already applied a 100 per cent tariff on them.

What about digital goods and services then? The virtual digital economy in 2025 is pretty massive. Meta’s fourth quarter 2024 results alone saw the company reap NZ$86.64 billion in revenue across its multiple online properties.

Most countries in the world import online goods like software apps, e-books, videos, music, games and digital services from the US but these are generally not seen as tariff-targets. Under the current United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), “customs duties and other discriminatory measures” against digital products are prohibited.

In fact, digital trade is highly encouraged under the USMCA, and facilitated with guarantees of free cross-border data flows. Whether or not the USMCA will survive Trump’s trade war with Canada and Mexico remains to be seen, however. If it doesn’t, digital trade could be in the crosshairs for customs duties.

That said, taxing online digital trade is complicated for countries. New Zealand only started applying goods and services tax for online transactions in 2016, extending it to overseas digital platforms like AirBnB and Uber in April last year.

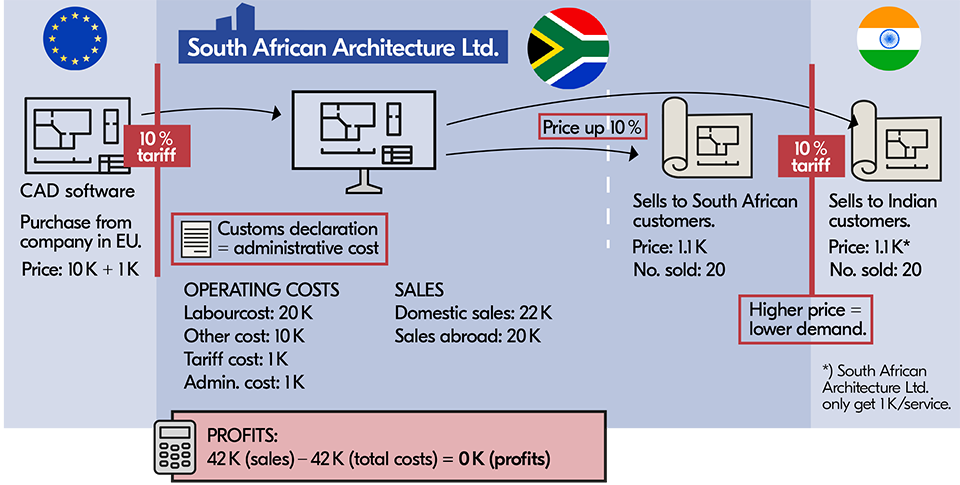

Traditional direct tariffs on the “weightless economy” with intangible goods and services being traded online would be awkward to implement and collect. Imagine having to fill in customs declarations and pay a tariff before downloading an application, or on software-as-a-service, ChatGPT, Starlink and Netflix subscriptions.

Instead, countries are looking at Digital Services Taxes (DSTs) which Canada already levies despite the USMCA. It was enough to give the US government an official nosebleed, with tariff threats starting to fly.

New Zealand is yet to implement its DST, to be levied at a modest three per cent flat rate on digital platforms. A tariff-happy Trump in the White House could further delay NZ’s implementation of DST, which was expected to start on or after January 1 this year.

At the global level, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has considered the “imposition of customs duties on electronic transmissions”. That move is currently placed under a moratorium since 1998, when the online economy was still a spring chicken and nobody really knew what would come out of it.

It’s a temporary moratorium that was renewed in March last year at WTO’s 13th ministerial conference. The way the world is tilting towards trade war, the moratorium might not be renewed at the next WTO ministerial conference in March 2026.

Sweden’s Kommerskollegium (National Trade Board), illustrates what would happen if the WTO moratorium goes.

The pain of online tariffs would be keenly felt by everyone. As the Swedish National Trade Board puts it:

“There are clear direct and indirect costs of imposing tariffs on electronic transmissions. For companies importing digital goods such as e-books or films, there will be a direct cost and increased administrative burden, which they will likely pass on to domestic consumers.

The indirect costs of the tariffs would be significant since software and data analytics are often intermediate input, used by almost all companies, and are crucial to increase efficiency and boost productivity.”

Indonesia is the only WTO member that has implemented customs procedures for digital goods, with importers asked to self-declare the value of them, and where the producer is located, the Swedish Trade Board said. Whether or not end-users count as importers when they download software or sign up for services is up in the air in Indonesia, it seems, and it's not clear what kind of system would be needed to manage customs processing if they are.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.