By Keith Woodford*

To a considerable extent, that perspective of a value chain that starts with production still survives within our animal-based agricultural industries. In contrast, the plant-based industries have been more successful in making the transition to a consumer-led position. And that may well be why, in an evolving world, our horticultural industries are currently succeeding where our traditional pastoral industries are currently struggling.

Our three big plant industries that are leading the way are viticulture, kiwifruit and apples. And then there are some other such as cherries which are also making good progress, plus seed crops such as carrots.

If we consider the ‘big two’ of kiwifruit and viticulture, neither were traditional industries to New Zealand. Both started from a blank page and had to find their own way. Both recognised not only that branding was essential, but that being ‘world famous in New Zealand’ was not going to be enough to take on the world.

The kiwifruit industry has certainly had its ups and downs, but the overall trajectory has been spectacular. The Zespri brand has leadership in many parts of the world. The Psa-V incursion in 2010 was traumatic, but in hindsight it has set Zespri on a new trajectory with the high quality SunGold variety.

One of the key reasons for the success of Zespri kiwifruit has been the recognition that international palates and New Zealand palates do not always coincide. So one has to go out to the market place and work with consumers to find out what will succeed in the international markets. But it is not only about the consumers themselves; it is also the cultural, regulatory and institutional environments that operate in these countries. And from there the path leads back to the science of variety development and on-farm production strategies.

Viticulture has taken a different structural path than the single-seller Zespri, in that there are many wine marketing companies. However, all of these wines are tied into their New Zealand provenance. In wine, branding is fundamental, but it still has to have foundations in science. It is perhaps a little sad that New Zealand wines are largely owned by foreign companies, which therefore earn the entrepreneurial profits. That is what happens in a country where people are spenders rather than savers. The equity capital has to come from elsewhere.

The apple story is different again. Apples grow well all over the world and New Zealand has no fundamental competitive advantage. For much of the last forty years, the apple industry was going backwards, tied to traditional thinking. Some fifteen years ago I considered it unlikely that our New Zealand apple industry would ever prosper. But somehow it broke loose from traditional thinking, and entrepreneurial companies have worked with the scientists to produce premium varieties which sell at premium prices. Once again, it started at the consumer end of the chain, combined with entrepreneurial thinking, and led back from there to production systems.

For much of my life I have worked in academia, albeit closely aligned to industry. So when I came back to New Zealand and Lincoln University in 2000, I thought a great deal about whether we could structure an agribusiness degree that started at the consumer end and which complemented the existing and highly successful production-focused agricultural commerce degree.

The basics of the model that I had in my mind came from University of Queensland, where I had been based, and where colleagues of mine had taken similar steps some ten years previously. That programme was particularly radical in that it included all undergraduate students undertaking a project, in groups of about five students, which took them to Asia with an ‘academic minder’ for some ‘on the ground’ market research on behalf of specific firms. It was certainly stressful at times – I recall once losing half my group in coastal China for 24 hours when a typhoon hit, the city went under water, and we had to travel to our hotel in a row boat. But the programme showed what could be done with industry support.

For a long time, I and my Lincoln colleagues were unable to get acceptance in New Zealand for a consumer-led undergraduate agribusiness degree, even without the radical option of taking all students to Asia on projects, which in the interests of stress management I had no wish to repeat. The concept of the degree was a step too far for traditional thinking and institutional politics. However, eventually we did make progress, and in 2014 more than ten years later, the first cohort of students finally entered the new Bachelor of Agribusiness and Food Marketing degree. This year the first students will graduate.

Overarching principles of this degree include that students must develop an understanding of food science. They need an understanding of marketing, and the complexities of working with food products. They also need to develop skills, via capstone courses, in the integration of science, markets, finance and people into agri-food systems. Within the limits of undergraduate teaching, they also need to develop skills in problem identification and problem-based learning, and also develop insights that, when they graduate, they have just taken their first steps in life-long learning.

We still had to make some compromises – in 2014 it was still very much a top-down environment at Lincoln – but in a changing environment even those issues are now starting to get sorted out. In the meantime, I and another colleague have moved on to other endeavours away from Lincoln, although I do retain some involvement. Others now carry the baton forward. As to the future, I am confident that the Agribusiness and Food Marketing degree will be one of the big three undergraduate degrees at Lincoln alongside agricultural science and agricultural commerce. It is also going to be a key degree that helps Lincoln further reach out to a global perspective.

A big question is the business environment in which these graduates will land. Will they find the challenges they seek within New Zealand or will many of them head overseas? Our horticultural industries, with their consumer focus, will be ready for them, but I am not so sure about the animal-based industries. Only time will tell.

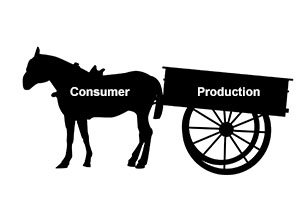

Within our traditional animal-based industries there remains a deeply ingrained belief that our pastoral products are so wonderful that overseas consumers surely must want them. We have never quite learned that the consumer is the horse and that production is the cart. Changing traditional ways of thinking is never easy.

Keith Woodford is Professor of Agri-Food Systems (Honorary) at Lincoln University and a Senior Fellow (Honorary) of the NZ Contemporary China Research Centre. His archived writings are at http://keithwoodford.wordpress.com

4 Comments

I think the picture above is fairly accurate, the only change i would make is there needs to be a carrot on a stick between the horse and the driver ( that carrot represents money printing and credit creation which is the only way to get the cart moving.)

Great article Keith. The storm clouds hanging over Lincoln are ominous. Looks like they will be required to flog off their farms and throw there lot in with Canterbury. Short sighted and totally contradicting the requirement to attract more talented young people into agricultural careers.

University senates and industry councils are all tarred with the same brush in my opinion, they protect the status quo and the interests of the participants.

We need way more renegades in New Zealand, people that make change happen.

Truth always rests with the minority, and the minority is always stronger than the majority, because the minority is generally formed by those who really have an opinion, while the strength of a majority is illusory, formed by the gangs who have no opinion — and who, therefore, in the next instant (when it is evident that the minority is the stronger) assume its opinion… while truth again reverts to a new minority. ― Søren Kierkegaard

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.