By Alpesh Bhudia, Anna Cartwright, Darren Hurley-Smith & Edward Cartwright*

In May 2023, the Dallas City Government was hugely disrupted by a ransomware attack. Ransomware attacks are so-called because the hackers behind them encrypt vital data and demand a ransom in order to get the information decrypted.

The attack in Dallas put a halt to hearings, trials and jury duty, and the eventual closure of the Dallas Municipal Court Building. It also had an indirect effect on wider police activities, with stretched resources affecting the ability to deliver, for example, summer youth programmes. The criminals threatened to publish sensitive data, including personal information, court cases, prisoner identities and government documents.

One might imagine an attack on a city government and police force causing widespread and lengthy disruption would be headline news. But ransomware attacks are now so common and routine that most pass with barely a ripple of attention. One notable exception happened in May and June 2023 when hackers exploited a vulnerability in the Moveit file transfer app which led to data theft from hundreds of organisations around the world. That attack grabbed headlines, perhaps because of the high profile victims, reported to include British Airways, the BBC and the chemist chain Boots.

According to one recent survey, ransomware payments have nearly doubled to US$1.5 million (£1.2 million) over the past year, with the highest-earning organisations the most likely to pay attackers. Sophos, a British cybersecurity firm, found that the average ransomware payment rose from US$812,000 the previous year. The average payment by UK organisations in 2023 was even higher than the global average, at US$2.1 million.

Meanwhile, in 2022 The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) issued new guidance urging organisations to bolster their defences amid fears of more state-sponsored cyber attacks linked to the conflict in Ukraine. It follows a series of cyber attacks in Ukraine which are suspected to have involved Russia, which Moscow denies.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

In reality, not a week goes by without attacks affecting governments, schools, hospitals, businesses and charities, all over the world. These attacks have significant financial and societal costs. They can affect small businesses, as well as huge corporations, and can be particularly devastating for those involved.

Ransomware is now widely acknowledged as a major threat and challenge to modern society.

Yet ten years ago it was nothing more than a theoretical possibility and niche threat. The way in which it has quickly evolved, fuelling criminality and causing untold damage should be of major concern. The ransomware “business model” has become increasingly sophisticated with, for instance, advances in malware attack vectors, negotiation strategies and the structure of criminal enterprise itself.

There is every expectation that criminals will continue to adapt their strategies and cause widespread damage for many years to come. That’s why it is vital that we study the ransomware threat and preempt these tactics so as to mitigate the long-term threat – and that is exactly what our research team is doing.

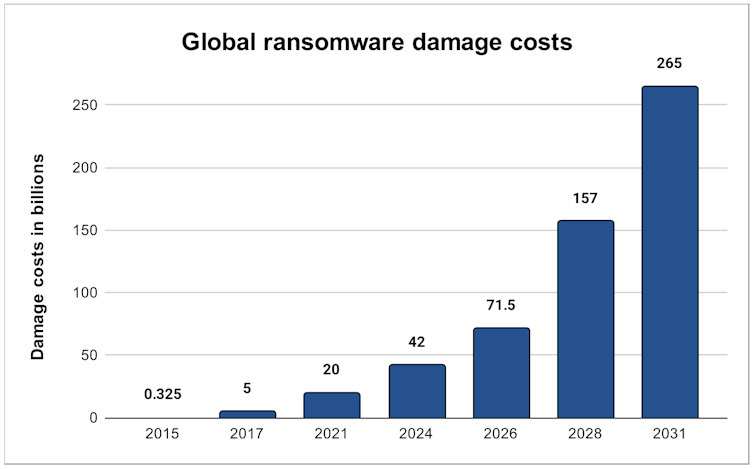

Prediction of global ransomware damage costs - source: Cyber Security Ventures

For many years our research has looked to preempt this evolving threat by exploring new strategies that ransomware criminals can use to extort victims. The aim is to forewarn, and be ahead of the game, without identifying specifics that could be used by criminals. In our latest research, which has been peer reviewed and will be published as part of the International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES), we have identified a novel threat that exploits vulnerabilities in cryptocurrencies.

What is ransomware?

Ransomware can mean subtly different things in different contexts. In 1996, Adam Young and Mordechai “Moti” Yung at Columbia University described the basic form of a ransomware attack as follows:

Criminals breach the cybersecurity defences of the victim (either through tactics like phishing emails or using an insider/rogue employee). Once the criminals have breached the victim’s defences they deploy the ransomware. The main function of which is to encrypt the victim’s files with a private key (which can be thought of as a long string of characters) to lock the victim out of their files. The third stage of an attack now begins with the criminal demanding a ransom for the private key.

The simple reality is that many victims pay the ransom, with ransoms potentially into the millions of dollars.

Using this basic characterisation of ransomware it is possible to distinguish different types of attack. At one extreme we there are the “low level” attacks where files are not encrypted or criminals do not attempt to extract ransoms. But at the other extreme attackers make considerable efforts to maximise disruption and extract a ransom.

The WannaCry ransomware attack in May 2017 is such an example. The attack, linked to the North Korean government, made no real attempt to extract ransoms from victims. Nevertheless, it led to widespread disruption across the world, including to the UK’s NHS, with some cybersecurity risk-modelling organisations even saying the global economic losses going into the billions.

It is difficult to discern motive in this case, but, generally speaking, political intent, or simple error on the part of the attackers may contribute to the lack of coherent value-extraction through extortion.

Our research focuses on the second extreme of ransomware attacks in which criminals look to coerce money from their victims. This does not preclude a political motive. Indeed, there is evidence of links between major ransomware groups and the Russian state. We can distinguish the degree to which ransomware attacks are motivated by financial gain by observing the effort invested in negotiation, a willingness to support or facilitate payment of the ransom, and the presence of money laundering services. By investing in tools and services which facilitate payment of the ransom, and its conversion to fiat currency, the attackers signal their financial motives.

The impact of attacks

As the attack on the Dallas City Government shows, the financial and social impacts of ransomware attacks can be diverse and severe.

High-impact ransomware attacks, such as the one which targeted Colonial Oil in May 2021 and took a major US fuel pipeline offline, are obviously dangerous to the continuity of vital services.

In January 2023, there was a ransomware attack on the Royal Mail in the UK that led to the suspension of international deliveries. It took over a month for service levels to get back to normal. This attack would have had a significant direct impact on the Royal Mail’s revenue and reputation. But, perhaps more importantly, it impacted all the small businesses and people who rely on it.

In May 2021, the Irish NHS was hit by a ransomware attack. This affected every aspect of patient care with widespread cancellation of appointments. The Taoiseach Micheál Martin said: “It’s a shocking attack on a health service, but fundamentally on the patients and the Irish public.” Sensitive data was also reportedly leaked. The financial impact of the attack could be as high as 100 million euros. This, however, does not account for the health and psychological impact on patients and medics affected by the disruption.

As well as health services, education has also been a prime target. For instance, in January 2023 a school in Guilford, UK, suffered an attack with the criminals threatening to publish sensitive data including safeguarding reports and information about vulnerable children.

Attacks are also timed to maximise disruption. For instance, an attack in June 2023 on a school in Dorchester, UK, left the school unable to use email or access services during the main exam period. This can have a profound impact on children’s wellbeing and educational achievement.

These examples are by no means exhaustive. Many attacks, for instance, directly target businesses and charities that are too small to attract attention. The impact on a small business, in terms of business disruption, lost reputation and the psychological cost of facing the consequences of an attack can be devastating. As an example, a survey in 2021 found that 34% of UK businesses that suffered a ransomware attack subsequently closed down. And, many of the businesses that continued operation still had to lay off staff.

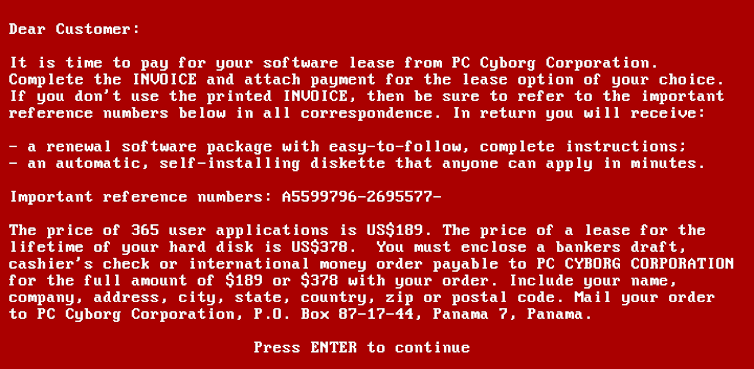

It began with floppy disks

The origins of ransomware are usually traced back to the AIDS or PC Cyborg Trojan virus in the 1980s. In this case, victims who inserted a floppy disk in their computer would find their files subsequently encrypted and a payment requested. Disks were distributed to attendees and people interested in specific conferences, who would then attempt to access the disk to complete a survey - instead becoming infected with the trojan. Files on affected computers were encrypted using a key stored locally on each target machine. A victim could, in principle, have restored access to their files by using this key. The victim, though, may not have known that they could do this, as even now, technical knowledge of cryptography is not common among most PC users.

Eventually, law enforcement traced the floppy disks to a Harvard-taught evolutionary biologist named Joseph Popp, who was conducting AIDS research at the time. He was arrested and charged with multiple counts of blackmail, and has been credited by some with being the inventor of ransomware. No one knows exactly what provoked Popp to do what he did.

Many early versions of ransomware were quite basic cryptographic systems which suffered from various issues surrounding how easy it was to find the key information the criminal was trying to hide from the victim. This is one reason why ransomware really came of age with the CryptoLocker attack in 2013 and 2014.

CryptoLocker was the first technically sound ransomware attack virus to be distributed en masse. Thousands of victims saw their files encrypted by ransomware that could not be reverse engineered. The private keys, used in encryption, were held by the attacker and victims could not restore access to their files without them. Ransoms of around US$300-600 were demanded and it is estimated the criminals got away with around US$3 million. Cryptolocker was eventually shut down in 2014 following an operation involving multiple, international law enforcement agencies.

CryptoLocker was pivotal in showing proof of concept that criminals could earn large amounts of money from ransomware. Subsequently, there was an explosion of new variants and new types. There was also significant evolution in the strategies used by criminals.

Off-the-shelf and double extortion

One important development was the emergence of ransomware-as-a-service. This is a term for markets on the dark web through which criminals can obtain and use “off-the-shelf” ransomware without the need for advanced computing skills while the ransomware providers take a cut of the profits.

Research has shown how the dark web is the “unregulated Wild West of the internet” and a safe haven for criminals to communicate and exchange of illegal goods and services. It is easily accessible and with the help of anonymisation technology and digital currencies, there is a global black economy thriving there. An estimated US$1 billion was spent there during the first nine months of 2019 alone, according to the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement.

With ransomware as a service (Raas) the barrier to entry for aspiring cyber criminals, in terms of both cost and skill, was lowered.

Under the Raas model, expertise is provided by vendors who develop the malware while the attackers themselves may be relatively unskilled. This also has the effect of compartmentalising risk – the arrest of cyber criminals using ransomware no longer threatens the entire supply chain, allowing attacks launched by other groups to continue.

We have also seen a movement away from mass phishing attacks, like CryptoLocker, which reached more than 250,000 systems, to more targeted attacks. That has meant an increasing focus on organisations with the revenue to pay large ransoms. Multinational organisations, legal firms, schools, universities, hospitals and healthcare providers have all become prime targets, as well as many small and micro businesses and charities.

A more recent development in ransomware, such as Netwalker, REvil/Sodinokibi, has been the threat of double extortion. This is where the criminals not only encrypt files but also exfiltrate data by copying the files. They then have the potential to leak or post potentially sensitive and important information.

An example of this occurred in 2020, when one of the largest software companies, Software AG, was hit with a double extortion ransomware called Clop. It was reported that the attackers had requested an exceptionally high ransom payment of US$20 million (about £15.7 million) which Software AG refused to pay. This led to attackers releasing confidential company data on the dark web. This provides criminals with two sources of leverage: they can ransom for the private key to decrypt files and they can ransom to stop publication of sensitive data.

Software AG said in a press release published yesterday that it found evidence that data was downloaded from its servers and employee notebooks. pic.twitter.com/K4XjI05DNB

— BleepingComputer (@BleepinComputer) October 9, 2020

Double extortion changes the business model of ransomware in interesting ways. In particular, with standard ransomware, there is a relatively straightforward incentive for a victim to pay a ransom for access to the private key if that would allow decryption of the files, and they cannot access the files through any other means. The victim “only” needs to trust the cyber criminal will give them the key and that the key will work.

‘Honour’ among thieves?

But with data exfiltration, by contrast, it is not obvious what the victim gets in return for paying the ransom. The criminals still have the sensitive data and could still publish it any time they want. They could, indeed, ask for subsequent ransoms to not publish the files.

Therefore, for data exfiltration to be a viable business strategy the criminals need to build a credible reputation of “honouring” ransom payments. This has arguably led to a normalised ransomware ecosystem.

For instance, ransom negotiators are private contractors and in some cases are required as part of a cyber insurance agreement to provide expertise in the managing of crisis situations involving ransomware. Where instructed, they will facilitate negotiated ransom payments. Within this ecosystem, some ransomware criminal gangs have developed a reputation for not publishing data (or at least delaying publication) if a ransom is paid.

More generally, the encryption, decryption or exfiltration of files is typically a difficult and costly task for criminals to pull off. It is far simpler to delete the files and then claim they have been encrypted or exfiltrated and demand a ransom. However, if the victims suspect that they won’t be getting the decryption key or encrypted data back then they won’t pay the ransom. And those that do pay a ransom and get nothing in return may disclose that fact. This is likely to impact the attacker’s “reputation” and the likelihood of future ransom payments. Simply put, it pays to play “fair” in the world of extortion and ransom attacks.

So in less than ten years we have seen the ransomware threat evolve enormously from the relatively low scale CryptoLocker, to a multi-million dollar business involving organised criminal gangs and sophisticated strategies. From 2020 onwards the incidents of ransomware, and consequent losses, have seemingly increased by another order of magnitude. Ransomware has become too big to ignore and is now a major concern for governments and law enforcement.

Crypto extortion threats

Devastating though ransomware has become, the threat will inevitably evolve further, as criminals develop new techniques for extortion. As mentioned already, a key theme in our collective research over the last ten years has been to try and preempt the likely strategies that criminals can employ so as to be ahead of the game.

Our research is now focused on the next generation of ransomware, which we believe will include variants focused on cryptocurrency, and the “consensus mechanisms” used within them.

A consensus mechanism is any method (usually algorithmic) used to achieve agreement, trust and security across a decentralised computer network.

Specifically, cryptocurrencies are increasingly using a so called “proof-of-stake” consensus mechanism, in which investors stake significant sums of currency, to validate crypto transactions. These stakes are vulnerable to extortion by ransomware criminals.

Cryptocurrencies rely on a decentralised blockchain that provides a transparent record of all the transactions that have taken place using that currency. The blockchain is maintained by a peer-to-peer network rather than a central authority (as with conventional currency). In principle, the transaction records included in the blockchain are immutable, verifiable and securely distributed across the network, giving users full ownership and visibility into the transaction data. These properties of blockchain rely on a secure and non-manipulable “consensus mechanism” in which the independent nodes in the network “approve” or “agree” which transactions to add to the blockchain.

Until now, cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin have relied on a so-called “proof-of-work” consensus mechanism in which the authorisation of transactions involves the solving of complex mathematical problems (the work). In the long term this approach is unsustainable because it results in duplication of effort and avoidable large scale energy use.

The alternative, which is now becoming a reality, is a “proof-of-stake” consensus mechanism. Here, transactions are approved by validators who have staked money and are financially rewarded for validating transactions. The role of inefficient work is replaced by a financial stake. While this addresses the energy problem, it means that large amounts of staked money becomes involved in validating crypto-transactions.

Ethereum

The existence of this staked money provides a novel threat to some proof-of-stake cryptocurrencies. We have focussed our attention on Ethereum, a decentralised cryptocurrency that establishes a peer-to-peer network to securely execute and verify application code, known as a smart contract.

Ethereum is powered by the Ether (ETH) token that allows users to transact with each other through the use of these smart contracts. The Ethereum project was co-founded by Vitalik Buterin in 2013 to overcome shortcomings with Bitcoin. On September 15 2022, The Merge, moved the Ethereum network from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake, making it one of the first prominent proof-of-stake cryptocurrencies.

The proof-of-stake consensus mechanism in Ethereum relies on “validators” to approve transactions. To set up a validator there needs to be a minimum stake of 32ETH, which is currently around US$60,000 (around £43,000). Validators can then earn a financial return on their stake from operating a validator in accordance with Ethereum rules. At the time of writing there are around 850,000 validators.

A lot of hope is being pinned on the “stake” solution of validation - but hackers are sure to be looking into how they can infiltrate the system.

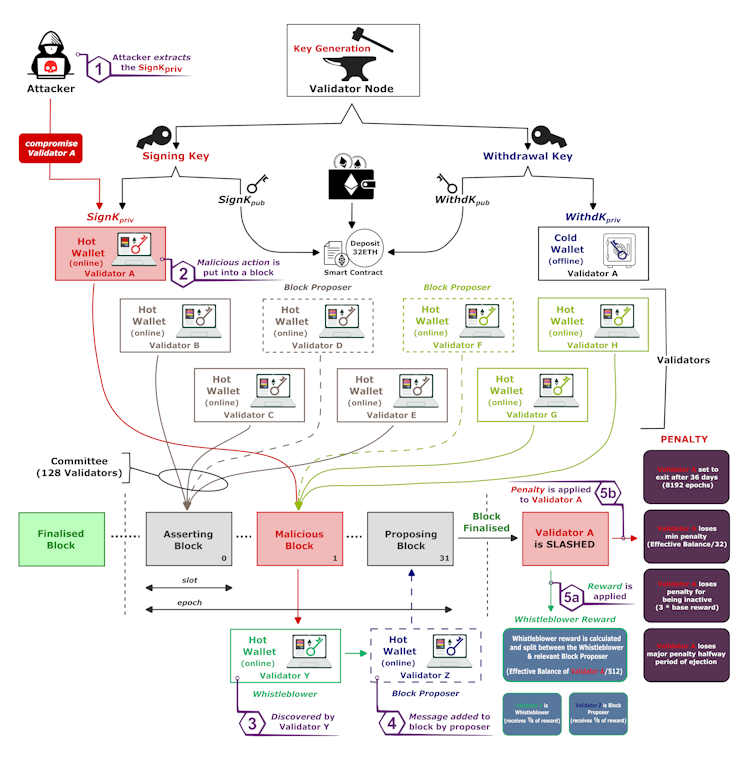

In our project, which was funded by the Ethereum Foundation, we identified ways in which ransomware groups could exploit the new proof-of-stake mechanism for extortion.

Slashing

We found that attackers could exploit validators through a process called “slashing”. While validators receive rewards for obeying the rules, there are financial penalties for validators that are seen to act maliciously. The basic objective of penalties is to prevent exploitation of the decentralised blockchain.

There are two forms of penalties, the most severe of which is slashing. Slashing occurs for actions that should not happen by accident and could jeopardise the blockchain, such as proposing conflicting blocks are added to the blockchain, or trying to change history.

Slashing penalties are relatively severe with the validator losing a significant share of their stake, at least 1ETH. Indeed, in the most extreme case the validator could lose all of their stake (32ETH). The validator will also be forced to exit and no longer act as a validator. In short, if a validator is slashed there are big financial consequences.

To perform actions, validators are assigned unique signing keys, that, in essence, prove who they are to the network. Suppose that a criminal got hold of the signing key? Then, they could blackmail the victim into paying a ransom.

Flow diagram showing just how complicated it gets when there is an extortion attack against proof-of-stake validators, such as Ethereum

A ‘smart contract’

The victim may be reluctant to pay the ransom unless there is a guarantee that the criminals will not take their money and fail to return/release the key. After all, what is to stop the criminals asking for another ransom?

One solution we have found – which harks back to the fact that ransomware has in fact become a kind of business operated by criminals who want prove they have an “honest” reputation – is a smart contract.

This automated contract can be written so that the process only works if both sides “honour” their side of the bargain. So, the victim could pay the ransom and be confident that this will resolve the direct extortion threat. This is possible through the Ethereum because all the steps required are publicly observable on the blockchain – the deposit, the sign to exit, the absence of slashing, and the return of the stake.

Functionally, these smart contracts are an escrow system in which money may be held until pre-agreed conditions are met. For instance, if the criminals force slashing before the validator has fully exited, then the contract will ensure that the ransom amount is returned to the victim. Such contracts are, however, open to abuse, and there’s no guarantee that an attacker-authored contract can be trusted. There is potential for the contract to be automated in a fully trusted way, but we have yet to observe such behaviour and systems emerge.

The staking pools threat

This type of “pay and exit” strategy is an effective way for criminals to extort victims if they can obtain the validator signing keys.

So how much damage would a ransomware attack like this do to Ethereum? If a single validator is compromised then the slashing penalty – and so maximum ransom demand – would be in the region of 1ETH, which is around US$1,800 (about £1,400). To leverage larger amounts of money the criminals, therefore, need to target organisations or staking pools that are responsible for managing large numbers of validators.

Remember, that given the high entry costs for individual investors, most of the validating on Ethereum will be run under “staking pools” in which multiple investors can collectively stake money.

To put this in perspective, Lido is the largest staking pool in Ethereum with around 127,000 validators and 18% of the total stake; Coinbase is the second largest with 40,000 validators and 6% of the total stake. In total, there are 21 staking pools operating more than a 1,000 validators. Any one of these staking pools is responsible for tens of millions of dollars of stake and so viable ransom demands could also be in the millions of dollars.

Proof-of-stake consensus mechanisms are too young for us to know whether extortion of staking pools will become an active reality. But the general lesson of ransomware’s evolution is that the criminals tend to gravitate towards strategies that incentivise payment and increase their illicit gains.

The most straightforward way that investors and staking pool operators can mitigate the extortion threat we have identified is by protecting their signing keys. If the criminals cannot access the signing keys then there is no threat. If the criminals can only access some of the keys (for operators with multiple validators) then the threat may fail to be lucrative.

So staking pools need to take measures to secure signing keys. This would involve a range of actions including: partitioning validators so that a breach only impacts a small subset; step up cyber security to prevent intrusion, and robust internal processes to limit the insider threat of an employee divulging signing keys.

The staking pool market for cryptocurrencies like Ethereum is competitive. There are many staking pools, all offering relatively similar services, and competing on price to attract investors. These competitive forces, and the need to cut costs, may lead to relatively lax security measures. Some staking pools may, therefore, prove a relatively easy target for criminals.

Ultimately, this can only be solved with regulation, greater awareness and for investors in staking pools to demand high levels of security to protect their stake.

Unfortunately, the history of ransomware suggests that high profile attacks will need to be seen before the threat is taken seriously enough. It is interesting to contemplate the consequences of a significant breach of a staking pool. The reputation of the staking pool would presumably be badly affected and so the staking pool’s viability in a competitive market is questionable. An attack may also have implications for the reputation of the currency.

At the most serious, it could lead to a currency collapsing. When that happens - as it did with FTX in 2022 following another hacking attack, there are knock-on effects to the global economy.

Here to stay

Ransomware will be a challenge for years, if not decades, to come.

One potential vision of the future is that ransomware just becomes part of normal economic life with organisations facing the constant threat of attack, with few consequences for the largely anonymous gangs of cyber criminals behind the scams.

To preempt such negative consequences we need greater awareness of the threat. Then investors can make more informed decisions over which staking pools and currencies to invest in. It also makes sense to have a market with many staking pools, rather than a market dominated by just a few large ones, as this could insulate the currency from possible attacks.

Beyond crypto, preemption involves investment in cyber security across a range of forms – from staff training and an organisational culture that supports reporting of incidents. It also involves investment in recovery options, such as effective back-ups, in-house expertise, insurance and tried and tested contingency plans.

Unfortunately, cyber security practices are not improving as one might hope in many organisations and this is leaving the door open for cyber criminals. Essentially, everyone needs to get better at hiding, and protecting, their digital keys and sensitive information if we are to stand a chance against the next generation of ransomware attackers.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.