For many years, people in retirement held their savings in bank deposits or similar fixed interest securities. The interest would be received (perhaps monthly, or perhaps six-monthly) and spent. On maturity, the investment would be rolled over into a new similar investment. This process was repeated and the continual rolling over of interest-earning securities and bank deposits was probably the main drawdown strategy for most retirees.

This strategy seemed to work reasonably well. Interest rates were higher than they are now, and the income received from interest payments was enough. Importantly, life expectancy was lower and people were probably less active than they are today and had fewer expenditure demands placed on them in retirement.

However, the higher interest rates were really an illusion at most times. Certainly, headline rates were higher (often much higher), but so too was income tax and inflation. Therefore, real interest rates (after inflation and tax) were often very low, even negative. People following this strategy were losing spending power each year and there was a great deal of talk about it all being very tough for people on ‘fixed incomes’ (a code for retired people).

In reality, although the rolling over of interest-bearing securities seemed to work, lower life expectancy masked the fact that it was not a good strategy. Quite simply, a lot of people died before inflation had a chance to wreck their retirement plans. In 1950, the retirement age was 60 years, meaning that on average people only enjoyed nine years of retirement. Today, with retirement age at 65, people on average have 17 years in retirement.

Therefore, today people must fund an additional eight years of retirement and low returns from interest-bearing investments that no longer work, if they ever did. Term deposits no longer cut the mustard.

At the same time, two other things have happened:

- People have become more willing to spend capital; and

- It is much easier to access financial markets which give higher returns.

There are still a good number of people who continue to be wedded to bank deposits and fixed interest investments. Such people think that these kinds of investments are safer, even though by taking out a term deposit you are almost certain to lose money in real terms. In my lifetime, there has been a swing towards diversified portfolios, and, although not everybody is quite there yet, things are improving.

Retirement income - the new way

While a few people still adopt the term deposit strategy, a much smarter plan is to have a diversified fund and draw a defined amount from this each fortnight. This diversified fund or portfolio could be a managed fund or funds (possibly a KiwiSaver account), a fund put together by a financial adviser, or, less commonly, a set of investments you directly manage yourself. A diversified fund will give exposure to all asset classes and be diversified within all asset classes.

At the moment, you cannot expect this diversified portfolio to spinoff much cash income - interest rates are still low, and so too are dividend yields. In the past, people may have lived happily enough on the interest and/or dividends they received but that is no longer the case. The idea of investing for income to live on is gone.

Instead, you will draw from the portfolio a set amount regardless of the cash returns that the portfolio or fund is returning. The fund will certainly make returns, but these will be made up of interest, dividends and capital gains.

These returns will accrue to the fund; however, it is quite likely that you will draw more than these total returns - and that means you will effectively be withdrawing a part of the capital, i.e. you will be running the fund down.

It is necessary for you to draw a pre-determined and constant amount because that is what you will be living on. You will draw on the fund every fortnight (or month) and that amount needs to be set at a level that will run the fund down - but not too quickly or too slowly. Over long periods of time the amount that you draw may change, however, over short periods of time (fortnightly or monthly), it will remain consistent as you draw down to pay bills.

It’s important to remember that you will not be living solely on the income or gains that the fund earns. The fund will have investment returns but almost regardless of what they are, you will draw down an amount that you have set at the beginning.

Spending capital

Whatever the drawdown rate you choose, unless it is very low it is most likely to include your investment returns and, each year, a little bit of your original capital as well.

Throughout retirement, you will make constant withdrawals - possibly following the 4% rule or some other rule of thumb. At the beginning of retirement, you will spend mostly investment returns and only a little of your investment capital. However, as time goes on and your capital gradually reduces, you have smaller investment returns (because you have less capital to generate returns) and so a greater proportion of your withdrawals from the portfolio is made up of capital.

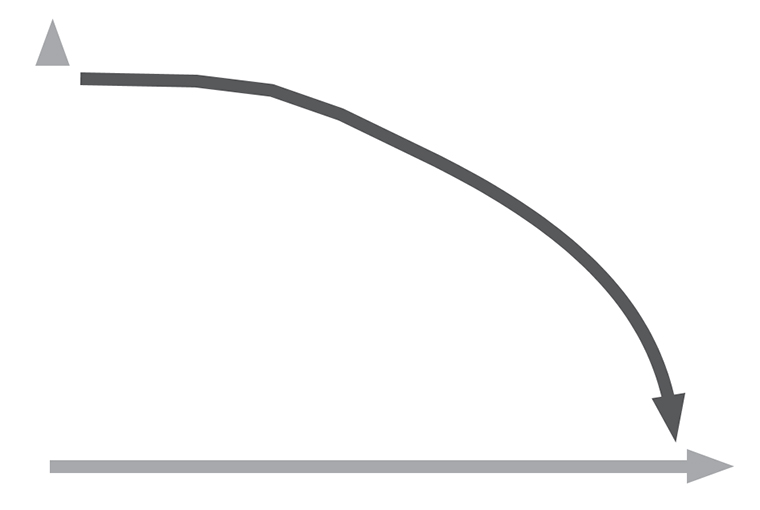

You may be drawing a standard $1,000 per fortnight from your investments but if you track the amount that you have in your investments, you will notice it reducing - slowly at first, faster towards the end. Graphically the amount that you have in your investment fund will look like this:

There is good way to think of this: imagine a couple who spend their whole lives as chicken farmers. They buy a dozen chickens (their capital) and, when they lay, they sell their eggs (their investment returns). However, they realise that selling a dozen or so eggs is not going to make them rich, and so, instead of selling all of their eggs, they hold one back each day (i.e. they save it). They keep this egg until it hatches, and this grows their flock. Saving that egg grows their capital and they end up with a magnificent flock of chickens, which lay plenty of eggs.

Come retirement, our farmers stop selling their eggs and instead start to consume them - eggs for breakfast, lunch and dinner (boring, perhaps, but nutritious enough). However, their eggs do not go quite far enough (they are not quite rich enough, there are not quite enough chickens laying) and so they must supplement their diet of eggs by killing the odd chicken. Roast chicken makes a welcome relief from all those eggs, but as chickens are killed and eaten, there are fewer to lay for them - and so the number of eggs available to eat reduces.

Gradually, the couple’s diet changes: they find that they are eating fewer eggs (income) and more chickens (capital). The race is on to see if they will have enough for their whole retirement - if they can get the timing just right, there will be no chickens to trade with the undertaker for decent funerals.

In the chicken farming example, there is a clear distinction between eggs and chickens, income and capital. In real life with a diversified portfolio, you will simply draw the same $1,000 each fortnight. Certainly, you will be able to figure out what your investment returns are, and you will be able to keep track of the amount of capital you have, but each fortnight, you will draw $1,000 regardless (or, nearly regardless - if the markets are in a serious downturn, you may stop or reduce drawings for a bit if you can).

The key for you is to decide how much you can draw down and still pay the undertaker. The chicken farmers had the same problem - they could have been gluttons or starved themselves. I could offer them no advice on this - I do not know the reproduction rate for chickens, nor have any idea the number of eggs or chickens you need to eat and have a good life.

Fortunately, when it comes to money, I am not so blind. This is because many people have the same drawdown problem, and we now have some rules of thumb to work from. These give the rate of drawdown which should be safe for you. They are not perfect because over the course of a long retirement anything might happen. They are, nevertheless, a good starting point and, even though you may need to make adjustments during retirement, they ought to give a fairly reasonable idea of how much to draw down each year.

Other drawdown ideas

I have frequently met people who have told me their retirement plans features rental property. This plan is to purchase a rental property, spend 20 years repaying the mortgage and then use the rent from the property to fund their retirements. For people in their forties, this all seems a good idea because it handles both the accumulation and decumulation phases in one fell swoop.

However, simply owning a rental property in retirement and relying on that for decumulation is not a good idea. It flies in the face of two of the critical requirements for decumulation that are set out above: a rental property is neither a liquid investment nor is it a diversified one.

In fact, it is a very concentrated investment and if a big majority of your retirement investment capital is in this property and you own little else you could strike trouble:

- Rental property may not perform as well as it has in the past (recent government measures which extended the Brightline test and removed the tax deductibility of interest could decrease returns and greater compliance could reduce cash returns).

- A big concentration of your wealth in rental property excludes having money in other asset classes, and especially stops you from having a significant proportion of your retirement

- It is hard to draw on capital. The rents may continue to flow and these, along with NZ Super may meet your basic expenses, but to get at your capital if needed, will almost certainly require a sale of the property.

- When all costs are factored in, residential rental property does not really give a great deal of income.

I would make similar comments to those who have a business and plan to try to keep their business when they ‘retire’. This plan may involve putting in managers or a business partner but, if the business’s value makes up a large proportion of the retiree’s wealth, it runs afoul of the two requirements for liquidity and diversification. It also does not allow for any kind of proper retirement. If you own a business, it is hard not to have at least some involvement and that involvement will likely be more than you want at times and may end up giving you continuous worry and work.

I see no alternative to a conventional diversified portfolio, probably one that is balanced (i.e. 50% is in growth assets and 50% in income assets).

This edited extract is from Cracking Open the Nest Egg by Martin Hawes. The book sets out to help people with the way they should invest when the nest egg has hatched, and how they draw down from their savings to give a good retirement.

40 Comments

Market capitalization isn’t “wealth.” It’s the latest price, times shares outstanding. Blotches of ink on paper. Flashing pixels on a screen. If a dentist in Poughkeepsie buys a single share of Apple at a price that’s 10 cents higher than the previous trade, $1.6 billion in market capitalization emerges from thin air. If a single share trades 10 cents lower, $1.6 billion evaporates just as quickly. Whatever happens, every security in existence has to be held by someone until it is retired. Ultimately, the wealth inherent in a security is the future stream of cash flows it will deliver to its holder(s) over time. Price fluctuations don’t change those underlying cash flows. They just provide opportunities for the transfer of savings between investors. High valuations favor the sellers. Low valuations favor the buyers. Investors have never paid higher prices for those future cash flows, or accepted prospective returns so low.

Put simply, the bubble hasn’t changed the wealth, and a collapse won’t change the wealth. What will change is the market cap. I suspect that the erasure of market cap in the coming years, and possibly the coming quarters, may be brutal. Still, no forecasts are required, and our own attention will remain on observable valuations, market internals, and other factors. Meanwhile, even if an investor sells at these extremes, the only thing that will change is who holds the bag. Link

"Investors" have persistently over capitalised the rising discounted present value of cash flows associated with assets, financed by bank credit as interest rates fell.

Policy makers sometimes flatter themselves with the idea that holding interest rates at untenably low levels makes it cheaper for borrowers to obtain funds. Unfortunately, it does so only by transferring income from people who are trying to save for the future. Replacing Treasury securities with base money may make savings more “liquid,” but it doesn’t suddenly make people abandon their retirement plans in favor of consuming today. Low rates also don’t magically create productive investment opportunities.

What economic activities suddenly become viable at zero interest rates that were somehow not viable before? Only projects so unproductive that any positive hurdle rate would sink them. The main activities that are encouraged by zero interest rates are activities where interest is the primary cost of doing business: leveraged real estate transactions; “carry trades” that employ enormous amounts of leverage to profit from small yield differences; and speculation on margin. Presently, margin debt as a percentage of GDP is at a historic extreme.

https://www.hussmanfunds.com/comment/mc210614/

The idea that “low interest rates justify high stock valuations” is really a statement that “low interest rates justify low expected stock returns as well.” Those high stock valuations are still associated with low prospective future stock market returns.

Worse, the notion that “low interest rates justify high stock valuations” assumes that the growth rate of future cash flows is held constant, at historically normal levels. If, as we presently observe, interest rates are low because growth rates are low, no valuation premium is “justified” by low interest rates at all.

Presently, the combination of record low interest rates and record high stock market valuations does nothing but add insult to injury.

...the iron law of investing is that a security is nothing but a claim on a future stream of cash flows. Valuation is a crucial determinant of long-term returns. The higher the price an investor pays for those cash flows today, the lower the long-term rate of return earned on the investment..

The corollary is also true. The lower the long-term rate of return demanded by investors, the higher the price moves today. So clearly, changes in investors' attitudes toward risk will strongly affect short-term returns. If investors become more willing to take market risk, it is equivalent to saying that they are demanding a smaller risk premium on stocks (that is, a lower long-term rate of return). Prices rise as a result. Now, the fact that current stock prices are higher also implies that future long-term returns will be lower, but that's part of the deal. Courtesy of Hussman Funds

.

Ho are you finding it? That is one option I've been thinking about, but what gives me pause is that I really enjoy being walking distance to everything (shops, park, doctors etc). I have older relatives who find the same - that being able to walk everywhere they need to go in 15-20 minutes is great for their quality of life. Do you find that being far from town it's downsides, or does it not really bother you?

Everyone is different I guess. I have always preferred countryside over city.

You're lucky.

In xx years we won't have a government funded pension.

I think you are right stjohn. All the more reason to be able to be self sufficient if you have to.

This is the worry. Means testing of super.

Even though it may not happen I am assuming that it will. I am buying long lasting assets now. I plan on having very little in the bank and no shares or bonds at about 70.

The threat of means testing of super is affecting my decisions right now.

Term deposits used to pay way more than CPI inflation. Not any more. Shares are over valued.

For me draw down has started in earnest.

So the conversion of the everything bubble (property, shares, bonds) into cash to sustain boomer retirement (goods and services), could be very inflationary.....and very bad for asset prices.

And oddly, holding cash in an inflationary environment is also very bad for ones purchasing power! So there is the possibility that nobody wins here.....except those who hold the physical commodities that people need and will use that cash to buy.

I guess the point I am trying to make in my post is that you don't necessarily have to always chase returns on a larger nest egg to cover high living costs, you can set yourself up to incur much lower living costs in retirement so that variable returns are less of a worry.

Along these lines: put in more insulation, get solar panels, plant fruit trees, learn to grow vegetables

Would you care to share some of assets you are thinking about? I'm still in my 30s but thinking about cutting living costs and working less, things like solar panels, better insulation, food production at home etc should all help.

Spare washing machine. Water tank. Garage so my car lasts a long time. Someone else said fruit trees. Thats a really good one. Trees to use as firewood in the future when the current trees have been used up. Composting bins. Exercise equipment. Stuff like that.

Fruit trees are only viable in some parts of NZ. Around Auckland you'll spend so much time and money tending to them to ensure a successful crop that they're not really worth it.

Self dependency is looking a wiser bet long term than investing in shares or term deposits. If you can become self reliant on power, water, and a decent chunk of your food intake then you're far less at the mercy of inflation.

The challenge is when you're too old to actively provide for yourself.

The other challenge or risk is location vs. hospital-level medical care.

Yeah I think in the past a lot of people who have sold up and moved to their holiday homes have later regretted doing that when they get a bit kernackered.

Central Otago on 2 hectares. It's wonderful but not cheap.

A difficult time to invest when there's the potential that everything is in a bubble....shares, property and bonds...

Then at the same time inflation is running away so holding cash if bubbles in all assets simultaneously burst also isn't a great option!

What a time to try and make good investment decisions.

Ray Dalio suggests diversification - across investment types, industries, across currencies....don't have all your eggs in one basket....this appears to align with what Martin is suggesting above (and I've read all of Martins investing/trusts books - thanks Martin :-) )

Strange timing for an article with interest rates on the up and up. Looking like a pretty good chance your 12 month TD will be back to between 4 to 5% next year. This provides a pretty good income if you have $500K sitting there.

He did take great pains to explain why an apparently high term deposit rate is misleading when the inflation rate is higher, as you're actually losing money in real terms. Currently inflation is over 6% and heading higher.

But the rising interest rates are supposed to slow down inflation, and get it back into the acceptable band. Otherwise won't they just keep pushing up the OCR? Plus these experts in these central banks have previously said that the inflation is only transitory due to supply issues.

Banks don't see to be passing on all the rate increases to savers, the online savings rates and bonus saver rates have barely risen at all. They seem to be making big margins.

Carlos - I think you might have missed the key message in the article - which is inflation adjust return.

But as you rightly point out the value of your TD isn't going to fall in nominal terms if interest rates rise (like a tradable bond might), but the real return of the TD is still negative so in terms of buying power that money is losing value for the duration of the investment.

I mean there's negative and less negative. For my mind, a TD or bank deposit with a lower interest rate but an actual deposit guarantee is a different proposition. As always, this is an insanely drawn out process to implement in NZ and at a fraction of the equivalent Australian scheme, but that tends to be how things go in NZ.

Do we still have no guarantee on bank deposits in this country? If so, we must be the only western country without it. Yet another reason not to have a TD.

Weren't they planning to implement a $100k guarantee a year or so ago?

No Gov guarantee. This Gov were considering it with a cap of $100k but it went nowhere. I believe Israel is the only other OECD country without a centrally backed Guarantee.

C H 66,

Out of date. A deposit guarantee scheme is coming next year at $100,000. Not all the details are as yet available, though I think that will be per person per authorised deposit taker. So, with $100000 in say 3 different banks, you would have cover of $300,000.

How does that make sense with real inflation currently at least 8-10% (and rising) then factor in tax as well.

And who has $500K sitting there?

Quite a few boomers do..especially those with low risk tolerance...and are cycling them through TD's as opposed to managed funds/bond funds/share portfolios.

Kiwisaver, negative returns for two years. A landed property seems like a good choice, for retirees.

You must have a mix of investments in your Kiwisaver quite radically different to mine. In particular, I guess you must be heavily weighted towards bonds holdings: the last time I checked (a couple of days ago) my Kiwisaver returned an average yearly net return of 17% p.a. for the last two years, after tax per year. I am with Superlife, which allows you to freely setup your own asset mix.

Given how ridiculously inflated the NZ housing Ponzi is at current levels (and so deeply out of synch with economic fundamentals), I would not touch residential housing with a barge pole. Commercial and industrial property, on the other hand, can still be an interesting proposition, if approached with eyes wide open.

I wouldn’t write residential property off as a long term investment provided that you stick with it. If you buy the right property , a graph of your net worth will be mirror image of the one above. In other words, exponential growth. Ditto the graph of rents. Don’t make 50 year plus investments based on last week’s news.

Real estate is an asset class where you can improve the asset after you buy it. Shares are not, unless you buy an awful lot and can exert some influence.

It does require some planning and knowledge, but so does any businesses. I've bought and developed a number of properties that I rent out profitably and have more money in my bank account than I started with.

Models that assume property involves paying the median price for something not suitable as an investment and renting at a loss will always make property look bad.

I have a few thoughts on this based on a long career in financial services in the UK and having had both a rental property and a share portfolio here for almost 20 years.

The rental property was bought for cash, is in the Mount and self-managed, while my share portfolio which I also manage, is based on the primacy of dividends over capital appreciation.

Both have done well, but the shares have outperformed the property by some margin. It is also considerably more flexible, a point made by Martin. However, my experience is backed up by good long-term statistical evidence from Mercers who operate globally. I have in front of me a table produced recently showing the performance of 16 asset classes over the past 10 years. This includes NZ equities(in which my portfolio is concentrated) and NZ property. In 8 of the 10 years, equities have outperformed property. The 2 years they did not were 2012 and 2021.

I think part of the reluctance of Kiwis to hold shares still stems from the '87 crash. It still gets mentioned, while in the UK, it was quickly forgotten.

Now, as I rapidly approach 77 and now with stage 4 cancer, my risk aversion has grown and I now keep a substantial amount in short-term PIE TDs for several reasons; security against falling markets, ease of access to capital and to buy back on a selective basis should the market fall further. Following my diagnosis, I was suddenly faced with needing in excess of $100,000 to fund the cancer drugs which were by best/only chance of holding it at bay. had I only held a rental property, I would have had no choice but to sell it which would have been very inefficient and quite costly. As it was, i had immediate access to the amounts in needed each month. If anyone is wondering, these drugs are working very well and the tumour has shrunk significantly. It is a great shame that they are not funded by Pharmac, but that's another story.

Thank you for your thoughtful comment. Sorry to hear about your cancer. Glad the medication is working. Wishing you all the best. Take care. Jo

jo147,

Thanks.I knew little about Pharmac until I was affected personally. Now i want to make as many people aware of the situation as possible. Short version; governments have seriously underfunded it for decades and now we lag well behind many other countries in the life-saving drugs we fund. Of course no government can fund every drug, but we could and should do more.

If interested, have a look at the Medicine Gap, it's an NZ site and the stories there illustrate the issues facing so many kiwis.

Very sorry to hear of what you're facing, linklater. Wishing the best for you.

"their eggs do not go quite far enough (they are not quite rich enough, there are not quite enough chickens laying)" Ah, the drudgery of human existence. Stay on the hamster wheel as demanded you pheasants!

"Today, with retirement age at 65, people on average have 17 years in retirement."

Jeez, talk about BASIC ERRORS...

Today, with retirement age at 65, people on average have 22 years in retirement - we are not dealing with life expectancy at birth. StatsNZ have a nice "how long will I live" calculator. Getting the years in retirement wrong by almost a third is worse than sloppy...

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.