By Patrick Watson*

Here we are in 2019, our last chance to make the Twenty-Teens a decade that worked. Whether you think it worked depends partly on whether you worked… and how well you were paid for it.

This time last year in Wages Are The Key to 2018, I said one scenario was, “Stronger-than-expected wage growth will make the Fed see inflation, tighten policy more than presently expected, and probably send stock prices lower.”

Sure enough, the Fed tightened more than people thought it would, and by the fourth quarter stock prices were indeed dropping.

But I also said the best long-term outcome was for higher wages to help workers recover their purchasing power, even if it meant short-term stock declines.

The weird part is, we got the bad without the good. The Fed tightened and stocks fell, but the average worker saw little or no real wage growth.

It wasn’t supposed to work this way.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Big wage gains?

Bigger paychecks seem like a good thing, on balance. Better-paid workers save and spend more, stimulating the economy, and the government gets more tax revenue. Even employers like higher pay if it brings more productive workers.

However, the Federal Reserve doesn’t think that way. Its job is to promote

- Maximum employment

- Stable prices

- Moderate long-term interest rates

Higher wages aren’t always consistent with those goals. They actually conflict with the Fed’s mandate if businesses raise prices in response—i.e., inflation. So when the Fed sees pay rising, its reflex is to “tap the brakes” by raising interest rates.

That’s what happened in 2017 and again in 2018—not because pay was actually increasing much, but because the Fed observed low unemployment and figured higher wages would be right behind.

Others agreed—even the president.

Donald J. Trump✔@realDonaldTrump

2018 is being called “THE YEAR OF THE WORKER” by Steve Moore, co-author of “Trumponomics.” It was indeed a great year for the American Worker with the “best job market in 50 years, and the lowest unemployment rate ever for blacks and Hispanics and all workers. Big wage gains.”

Unfortunately, this isn’t quite right. The Labor Department says average hourly earnings rose 3.2% in 2018 while CPI-U inflation (through November) was up 2.2%. That means these “big wage gains” were, after inflation, only 1%. Yippee.

This wasn’t the case for everyone; it’s a national average. Some people did better than average, others worse… and it appears the latter group was bigger.

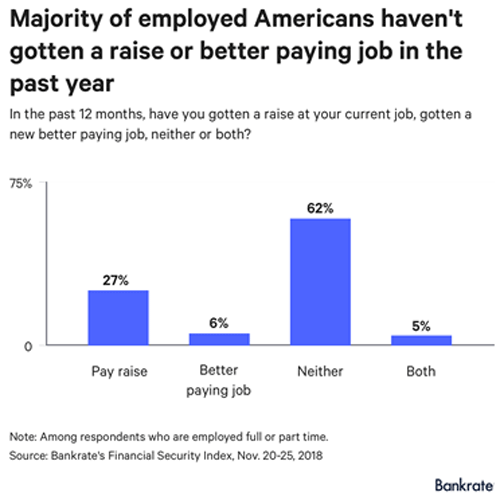

In a November Bankrate survey, 62% of employed Americans said they hadn’t received a pay raise or taken a better-paying job in the last year.

Chart:Bankrate.com

If this data is right, 2018 wage gains were both mild and concentrated in about one-third of the workforce. The rest still made the same as a year ago (or possibly less).

Lesser of two evils

Now, does this look like an overheated economy that needs cooling? I don’t think so. But the Fed is cooling it anyway.

Here’s what the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) said in the minutes from its November meeting:

Participants observed that, at the national level, measures of nominal wage growth appeared to be picking up. Many participants noted that the recent pace of aggregate wage gains was broadly consistent with trends in productivity growth and inflation.

Let me decode this for you.

“Nominal” wage growth means growth before inflation. Which is picking up, as I noted above.

“Broadly consistent with trends in productivity growth and inflation” is more nebulous. They seem to be saying wages aren’t really changing much, once you consider added productivity and inflation. Which is also true, but it isn’t an argument for rate hikes, so why say it?

The answer, in my opinion, is that the Fed’s real goal in raising rates is to be able to cut again in the next recession, which may not be far away. If that suppresses wages in the meantime, the Fed figures it’s the lesser of two evils.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Shrinking pay

This isn’t a new or recent problem. Wages have lagged for most American workers for decades now.

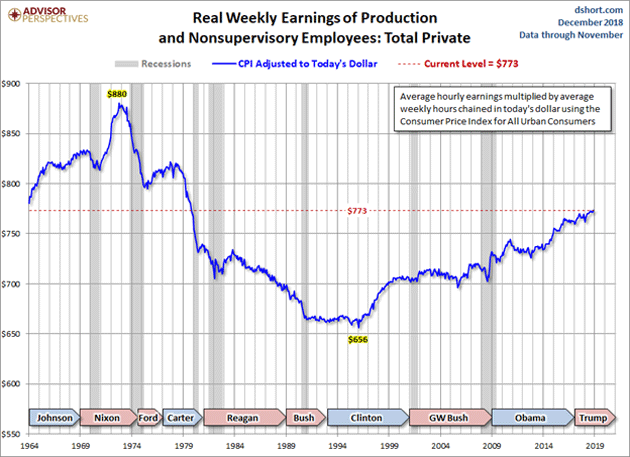

The dollar amount shown in the blue line below is average hourly earnings, multiplied by average weekly hours, and then adjusted for inflation.

The underlying data is also for “production and nonsupervisory employees” only. It excludes managers, executives, and other high-paid employees. So this reflects the typical worker’s pay, considering both inflation and varying hours.

Chart: Advisor Perspectives

Crunching all that together, American worker pay peaked in the early 1970s, bottomed in the mid-1990s, and has been slowly climbing back ever since. It is still below where it was 50 years ago.

Hard to believe? You could argue with the inflation adjustment. Other things have changed as well. For instance, non-cash fringe benefits are a bigger part of compensation now.

But those are getting scarcer too, so I doubt they change the broader point: The US labor market is broken. Working hard and improving your skills doesn’t deliver the American Dream for most workers... and hasn’t for a long time.

Given that, it’s no surprise people are angry and demanding change. Thus far, it has not appeared. Monetary and fiscal policy are arguably making the average worker’s situation worse, not better.

What will 2019 bring? We’ll find out, but unless it includes widespread and significant wage gains, I don’t expect much big-picture improvement this year.

That is a problem, even if you are a wealthy investor. Stock prices are the present value of expected future earnings, which will materialize only if consumers can afford what your company sells.

Consider adjusting your expectations.

*Patrick Watson is senior economic analyst at Mauldin Economics. This article is from a regular Mauldin Economics series called Connecting the Dots. It first appeared here and is used by interest.co.nz with permission.

6 Comments

Insightful. My time in the states led me to conclude it may no longer be the home of the free and nor is it anywhere near a workers paradise...but it certainly is the home of the fee....

Why should the shareholders of the global corporation/employers share their income /wealth with workers in a country? There is no obligation or loyalty to the citizens where they are based transnationally.

That's ultimately been the effect of globalisation, yes. Tax domiciling.

So it's up to societies to decide how they want to address that. Options? Taking ownership stakes in these companies? Tax policy? Other?

The widening gap between the haves and the have nots is one of the five key ingredients in the decline of the world's main dominant cultures over the past 3,000 years. If you agree with that then you should be cheering Trump on from the sidelines.

Yeah I guess the gap will be less when the whole country goes broke!

I wonder if there a number of hidden facets that are not considered here. Firstly those businesses who did not give pay rises to their workers - were they making a growing profit? There is ample news out of the US of many large, and likely small businesses struggling in difficult markets, and giving a payrise when you are marginal would be suicidal. Productivity growth may be the only thing keeping them afloat. Secondly , and possibly being a bigger problem in NZ than the US is regulatory costs. The cost of operating a business, tax, Health and Safety, insurance, licences, certification, suppliers and so on can be crippling and in a diffuclt economy some of these can actually go up.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.