“The Fed’s emergency policies since 2008 have in one sense been a huge success, though we will never know the counter-factual. A great depression was averted. Output is 10pc above its previous peak. Employment is up by 4.7m.

“Yet zero rates and QE set off torrid credit bubbles in the emerging world, pushing up the global debt ratio by 30pc of GDP beyond their previous record in 2008. The Bank for International Settlements calls this a “Pareto sub-optimal” for the world as a whole. The chickens have not yet come home to roost.”

– Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, The Telegraph

For seven long years, under two presidents and two chairpersons, the Federal Reserve kept its key policy rate effectively at zero. Now those years are over. We’re entering a new era – but new isn’t necessarily better.

Just for fun, I looked back to Thoughts from the Frontline for December 19, 2008 – right after the Fed first dropped rates to zero. You can read it here: “I Meant to Do That.” The theme with which I opened that issue could have worked just as well today, although we now have a different circumstance: rising rates.

The Fed has taken interest rates to zero. They have clearly started a program of quantitative easing. What exactly does that mean? Are we all now Japanese? Is the Fed pushing on a string, as Japan has done for almost two decades? The quick answer is no, but the quick answer doesn't tell us much. We may not be in for a two-decades-long Japanese malaise, but we will experience a whole new set of circumstances.

Indeed, we now face that whole new set of circumstances. The Federal Reserve has created a series of debt and credit bubbles all over the world. The Bank for International Settlements terms this a “Pareto sub-optimal” for the global economy.

On the other hand, to say that the Fed “tightened” this week amounts to a very generous use of the word. They still own a multi-trillion-dollar Treasury and mortgage-bond portfolio in which they continue to reinvest anything that matures or pays interest. Last week’s FOMC statement pledged to “maintain accommodative financial conditions.” No one should call this crew hawkish – just marginally less dovish now.

In today’s letter we are going to examine the problematic credit markets, and I want to focus on something that is happening off the radar screen: the continuing rise of credit in private lending. I predicted the rise of private credit back in 2007 and said that it would become a major force in the world, but I got strange looks from audiences when I talked about the arcane subject of private credit. Today the shadow banking system is taking significant market share from traditional banking. Thus the market is gaining greater control over many of the traditional levers that central banks like to push and pull. While I think that trend is generally a good thing, it means that central banks are going to have to lean even harder in their policy directions if they want to affect the markets. And since they do like to interfere, it won’t be long before we embark on a “whole new set of circumstances.”

Breaking the Bonds

The Fed’s reversal comes at an interesting (pun intended) time for credit markets. If the financial crisis ripped the fixed-income sector apart, the years of ZIRP served to reassemble it. However, the new version only superficially resembles the old one. A fixed-income market in which the only fixed element is an interest rate fixed at zero is not something that would arise naturally. It exists only because someone twisted nature into a new shape. And as we all know, it’s not nice to fool with Mother Nature. She always takes her revenge.

ZIRP distorted the economy and the financial markets in countless ways. Remember when we had a “risk-free rate of return?” We used to regard the 30-day Treasury bill rate as a benchmark. It figured into metrics like the Sharpe ratio. If you could make 5% on your money with no risk, any manager who only delivered 3% would have to polish his résumé.

I hear you asking, what is this 5% return you speak of? Believe it or not, Treasury bills really yielded 5% as recently as 2006, right before the Fed began the easing cycle that ended this week. Everyone, myself included, thought that was perfectly normal. Returns in that range or even much higher had been our experience for 50 years, other than a brief stay just below 1% in the early-2000s recession. T-bills had always given us a nicely positive yield. No one imagined any other possibility.

That world in which 5% was the minimum return you’d expect from any manager worth his salt is pure fantasy now. We just finished seven years in which achieving returns with a + sign in front of them required taking on risk.

We’ve been able to choose our poison. We could take credit risk, inflation risk, equity risk, hedge fund risk, hurricane risk (seriously, you can) – any risk we liked. The one thing we weren’t allowed to have was daily liquidity with returns above zero as a certainty. It was the Age of the Guessing Game.

The ways in which the Fed has changed investor behavior are legion. By creating an environment that forced everyone to take risks, Ben Bernanke moved liabilities (i.e., deposits) out of the banking system and into risk assets. This helped the banks rebuild their mortgage-laden balance sheets.

Quite naturally, and as a direct consequence, the price of risk assets rose as everyone piled into them. Stocks were only one example. Look at housing, as well as most natural resources. They rose nicely while ZIRP reigned, as did assets all over the emerging-market world, setting up the crash of the past year. Bernanke’s 2013 QE “taper” comment was a big hint that change was coming. It took longer than anyone thought, but now that change is here.

As Ambrose points out, the Fed typically needs about 350 basis points of rate cuts to be able to work its “magic” on the economy. Although Fed governors project about 100 basis points of interest-rate hikes in the coming year, the market is seeing only two hikes of 25 basis points apiece. I’ll go with the market.

The Federal Reserve economists and board members’ projections assume no recession through 2019. If history has anything to say, they will be wrong. And while my opinion carries nothing like the weight of history, I personally think they will be wrong, too. We have already had the third longest “recovery” (weak as it is) following a recession since World War II. To think we can go without a recession for another full two years, through 2017, strains credibility. We will need to get well into 2018 or 2019 before we see the Fed’s projected funds rate of 3.5%.

I will repeat my wager from earlier this week: I think the chances that we’ll see 0% interest rates before we see 2% interest rates are better than 50-50, and I will give odds that we don’t see 3% before we are back to 0%.

That means the Fed will not have enough “bullets” in its interest-rate-cut arsenal. If the US goes into recession, a global recession is likely to follow. The world has never seen a full-blown recession with interest rates this close to 0% in both the US and Europe. The stimulus central banks would apply to stave off that recession would be staggering. Whether or not their Hail Mary pass would work is another question. That last-ditch effort would make the previous period of QE look like a stroll in the park.

Sucking Out Liquidity

A sideshow to this grand monetary experiment played out on Capitol Hill. Congress, as it often does, observed the horses escaping to the north 40 and decided it should close the barn door. It did this with the Dodd-Frank financial reform law.

Like much legislation, Dodd-Frank has given rise to major unintended consequences. For instance, the “Volcker Rule” has sucked liquidity out of the bond markets. Liquidity does not materialize from nowhere; someone has to provide it. That person or institution doesn’t work for free. Yet the Volcker Rule leaves little room for profit, for banks at least.

The result, for now at least, is that banks hold a fraction of the bonds in inventory that they used to. You may applaud or decry this outcome, but it is a reality, and it reduces banks’ ability to fill the market-making role they once did. Which means that when there is forced selling in the credit market, like we’ve seen the past month, the banks aren’t there to provide liquidity. Over time, new private institutions will develop to provide that liquidity, at a price. But until that time, volatility will be the rule.

Private Credit Reaching Maturity

More than eight years ago I predicted that the private-credit world would explode into equal prominence with private equity within a few decades. I’m clearly on target for that prediction. It may happen a lot sooner. I’ve been a fan of private credit for a long time.

Recently, I have once again been exploring the private-credit world. The term encompasses a whole range of investments. The common thread is that they involve non-bank lending. This market is far bigger than I had thought.

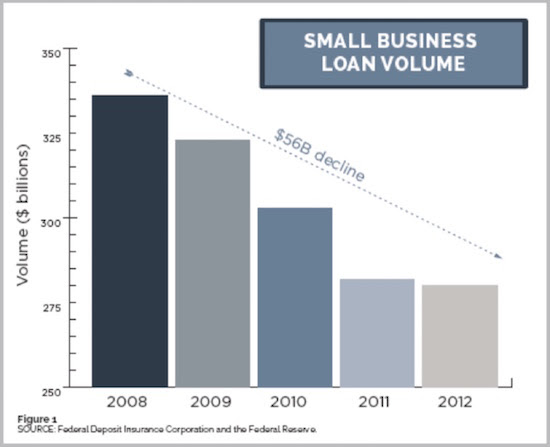

Much of the growth in private credit is a direct consequence of declining bank lending. Between the financial crisis and new restrictions like Dodd-Frank, banks have had to seriously tighten their lending standards. Moreover, they’ve had to cut back in ways that don’t make sense. I talk to a lot of small-bank executives and directors. They constantly complain that the regulators are forcing them out of profitable markets and making it impossible for them to do business. I can’t help but sympathize, because they are right. But this regulatory restriction is creating a huge opportunity for the creation of private lending.

Meanwhile, not only are banks operating illogically, they are centralizing the illogic. The giant Wall Street banks have been snapping up local and regional banks, thereby eliminating the hands-on, personalized approach to lending. Most banks are now highly centralized bureaucracies. That’s great if your need is shaped like their cookie cutter. If it isn’t, the big bank can’t help you.

Fortunately, the economy is still free enough to create alternatives to fill the gaps. Non-bank lenders are leveraging technology to supply credit in the niches banks ignore.

You might have heard of the online peer-to-peer lending platforms like Prosper and Lending Club. They connect people and businesses that need to borrow money with investors who have money to lend. They make a match that can give both sides the terms they want.

Here is an example I ran into last week on Lending Club. Say you want a $25,000 debt-consolidation loan. Your FICO score is in the “good” range – 660-720 – and you have annual income over $100,000. With Lending Club you can get a five-year loan at 7.89% with a 3% origination fee. That works out to a 9.63% APR, less (and in some cases much less) than most credit cards charge.

Where does this money come from? Investors buy packages of loans that may contain thousands of loans like the one outlined above. Lending Club claims its top three credit groups have delivered historical returns ranging from 5.23% to 8.82% with very modest risk.

Modest risk is not the same as no risk, of course, but we’ve already established that risk-free investing pays you little or nothing. It certainly doesn’t pay 5% or more. Peer-to-peer lending through these platforms can earn you a substantially higher income than a corporate bond fund with similar maturity.

The difference is liquidity. You can escape the corporate bond fund or ETF with a few mouse clicks any time the markets are open. You can’t do that with P2P. Giving up that liquidity earns you a higher return.

(I use Lending Club only as an example, by the way. I have no affiliation with them, nor have I done any significant due diligence. Do your own homework, or have your investment advisor do it, if you want to consider investing in P2P loans.)

P2P is only the surface layer of the private-credit market. It can be a good option for people with relatively small portfolios. Accredited investors and institutions have many more choices. These are hard to find, but the ones I’ve seen are even more compelling than P2P.

------------------------------

* This is an abridged article from Thoughts from the Frontline, John Mauldin's free weekly investment and economic newsletter. It first appeared here and is used by interest.co.nz with permission.

3 Comments

A timely and obvious article. Capital tends to flow to the lowest risk/return ratio acceptable to the lender, so the emergence of P2P and other forms of non-bankster lending should be no surprise to anyone who understands human behaviours.

The trick, as with much in life, is to avoid P2P'ing oneself into the equivalent of an Offal Pit - neatly defined by NZ Farmer as possessing the ability to render one unconscious (or your capital illiquid, compromised or just plain Gone) http://www.stuff.co.nz/business/farming/75362579/ten-tips-to-prepare-to…

Out of all my farming cuzzies , most are now town based. The link between town and farm is very close.

You may not be allowing enough for egos and dogma IMHO. So its quite likely Yellen will continue to rise or even hold when it looks wrong and will drop too slow, too late. If Trump wins and we still have a Republican Congress it will happen sooner though.

May you live in interesting times as the curse goes.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.