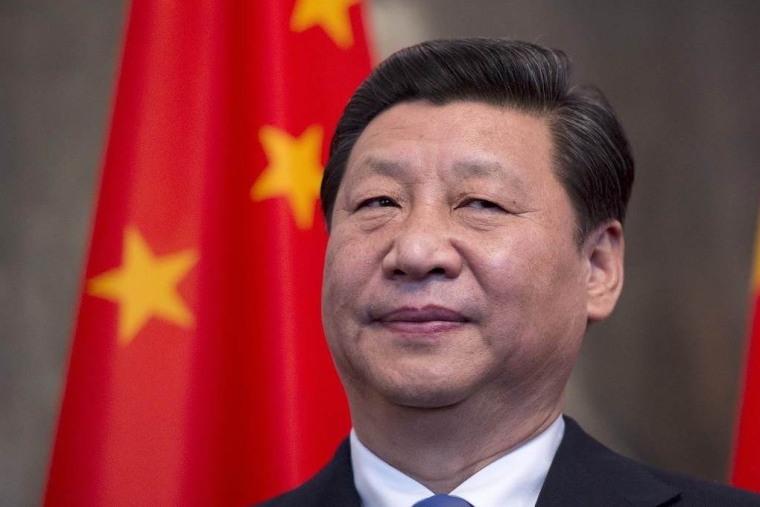

To what degree is Xi set to become the all-powerful ruler many observers predict?

China watchers have been debating the character and extent of Xi’s power since last October’s 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC). One indicator has been the enshrinement of his ideology, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” in China’s constitution. With Mao Zedong being the only previous Chinese leader to have his eponymous “Thought” constitutionalised, some now argue that Xi is now the most powerful leader since Mao.

Of course, Deng Xiaoping – who presided over China’s era of “reform and opening up” for two decades, beginning in 1978 – was also lionised, with “Deng Xiaoping Theory.” And “socialism with Chinese characteristics” is Deng’s signature policy. But Xi’s explicit mention of a “New Era” marks a departure from Deng, indicating that the era of reform is over.

In contrast to the People’s Republic of 40 years ago – a rural, agrarian country emerging from the Cultural Revolution – today’s China is an economic and political superpower with a rapidly urbanising and technologically advanced society. Xi’s New Era thus represents a milestone in China’s long search for “wealth and power.” Instead of “opening up,” Xi’s China will be “going out” to the world.

But how should this New Era be viewed in the context of modern Chinese history, and what might it reveal about the nature of Xi’s power?

In the twentieth century, China was governed by three regimes: the Qing dynasty, followed by the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, and, since 1949, the People’s Republic of China. The history of the PRC is further divided into two periods: the Mao era (1949-1976) and the reform era.

How this history was perceived changed over time. During the Mao years, the Republican era – with its “united front” politics and the development of civil society– looked like a brief interlude between periods of autocracy. Yet, during the PRC’s reform period, it was the tumult of the Mao era that looked like the aberration, even to the CPC, which sought to distance itself from what it called “leftist mistakes.” With the success of Deng’s “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” China’s economic miracle appeared to confirm that the country was firmly on the path toward development and modernisation.

Changing perceptions of China’s trajectory have been reflected in America’s relationship with the country. During World War II, China was America’s ally. Indeed, in 1943, the wife of China’s Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek testified before the US Congress about how US President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “four freedoms” applied to a China at war with Japan.

But the belief that the US-China relationship was based on shared values was dashed by the CPC’s victory in 1949, leading to the suggestion that the US had somehow “lost China.” Such hopes were revived, to some extent, with the reestablishment of diplomatic relations and, later, the reform era. Believing that economic development and a growing middle class would lead to political liberalisation, the US again engaged with China.

This hope was reinforced through the 1990s and 2000s, when officials began to experiment with elections at the village level, and the CPC leadership changed regularly after two terms. China joined the World Trade Organisation and hosted the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. As the journalist Jim Mann once argued, it was the expectation of political reform that underlay US interactions with China, even after the massacre in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Yet, over the last decade, that expectation has been called into question. While China’s per capita income was rising, and its middle class was growing, democracy did not arrive. Political scientists stopped predicting the CPC’s collapse and began asking instead why the one-party authoritarian state has been so resilient, and whether the period of reform and opening up had come to an end. As Xi’s “New Era” shows, the answer is a resounding yes.

Consider the rise of digital technologies. Instead of allowing the Internet to result in greater freedom, China’s government constructed a Great Firewall. At the same time, it developed what political scientists call “digital Leninism,” in which the latest technology enables an unprecedented level of state surveillance.

Similarly, China’s market economy has not grown increasingly privatised. Instead, the government has maintained control of the most important state-owned enterprises, and the private enterprise that is conducted serves state priorities. In the realm of politics, democratic experimentation is confined to the local level, permitted only insofar as it strengthens CPC rule.

So was the reform era yet another aberration in China’s history, not unlike the Republican period? One way to approach this question is to imagine modern Chinese history as resembling the double-helix structure of DNA, comprising a strand of openness and one of authoritarianism.

For example, many think of the reform era, especially the 1980s, as a time of pluralistic political discourse and an increasingly vibrant civil society. But it was also defined by adherence to Deng’s “four cardinal principles”: the socialist road; the people’s democratic dictatorship; the leadership of the CPC; and Marxism, Leninism, and Mao Zedong Thought.

Just as Deng presided over China’s reform and opening up, he presided over the Tiananmen Square massacre. Similarly, while the Republican era had its new universities and professions (including lawyers), it also had Chiang Kai-shek’s “White Terror” and the conservative “New Life” movement.

In short, even when the Chinese tapestry featured a reformist weft, it was always woven into an authoritarian warp. In Xi’s “New Era,” it is the authoritarian strand that is dominant. History will tell whether a recessive strand of openness may persist.

Denise Y. Ho is a professor of history at Yale University and the author of Curating Revolution: Politics on Display in Mao’s China. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2018, and published here with permission.

8 Comments

An interesting perspective. Hopefully our two list MPs who grew up in China will contribute comments; to date they have been very cautious about anything that might seem critical of the CPC.

2,958 to two – to abolish presidential term limits, that's mighty impressive.

I guess it makes sense, when you have a good one, to keep him on.

Keep in mind that this doesn't mean President for life, just that you don't need to step down once the limit has been reached. Indeed NZ has no such limits as far as I am aware.

Xi has been able to take advantage of the turmoil in Western politics to push this through. The Democrat's constant calls to impeach Trump and the Western media's proven anti-Trump bias, the rise of the ultra-Right, insanely stupid Russia conspiracy theories, pointless and catastrophic wars, supporting terrorism, suppression of free speech, inability to defend borders and just general stupidity of Western folk has only made Xi more godlike in the eyes of the majority of Chinese people, even ex-pats. Why would they adopt Western democracy when the West is so clearly in decline, morally, spiritually, intellectually, even financially and China is ascending? Why would you? That would be madness wouldn't it?

At least it wouldn't be too hard to spin that narrative.

All quite correct regarding the low appeal of Western democracy at the current time.

I would add that we ourselves have enabled both our decline and the rise of China. China today would still look much like China of the 1960's - overpopulated, underdeveloped and lacking modern manufacturing & technological know-how - had it not been for Western companies (foolishly) investing en masse in China since the 1980's in the pursuit of "low cost" manufacturing.

The Chinese have played the long game whereas we have played the "make a quick buck" game. They have insisted on joint-venture partnerships when setting up shop in China, they have robbed IP through overt & covert means, they have protected key nascent industries, and have leveraged their economies of scale to create a modern industrial base that out-competes the Americans, Japanese & Germans.

On the other hand - the rise of the Rust Belt, the rise of populist politics, the decline in educational and vocational opportunities for the middle & working classes across the Western world can be attributed to the decision by Western companies (and aided by Western elites) to ditch home-grown labour and invest in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand and the like. As a uni student in the 1990's it was a constant subject of study - the New International Division of Labour; the Asian Tigers; the growth of the Multi-National that could ignore national borders, take advantage of lax labour & environmental laws and headquarter itself in exotic locations to avoid paying tax. The old saying is no longer true - What's Good for General Motors is Good for America.

So, if we want to avoid becoming the under-educated, ignorant *and* unemployed serfs of the 21st century global feudal economy all of these things need to be reversed immediately. Indeed, the simplest course of action and the most sincere form of flattery would be to simply copy China.

I am starting to wonder if I might actually see a prediction my father made many years ago (he died in the mid seventies, so it does go back a bit). He maintained that if the US and Russia ever went to war, China would be the victors.

China and Russia both won the Vietnam war.

Has any country won a land based war since.

Vietnam vs Cambodia?

A bitter truth here is that giant countries like China and Russia would always try to dominate any nearby including those in Pacific or even Oceania region. A good example of how diverting the current labour and national fight on party harassment from the hot topic of Chinese spies. They exist and will exist until the whole country got under control directly or indirectly by the these two nations.

Very interesting article, thanks.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.