By Richard Easther*

New Zealand’s research community is up in arms over abrupt changes to the Marsden Fund, which is our primary source of support for open-ended aka blue-sky research. The outrage centres on government’s decision to remove funding for the humanities and social sciences, and a requirement that the fund returns economic benefits.

Many voices in the chorus of outrage have homed in on matters of principle: that pure research is important in its own right, and that the humanities have as much to tell us about ourselves as physics or chemistry (see for example this one, these people and also those people).

But to my eye, there is also a pragmatic issue with actively obliging the Marsden Fund to deliver economic outcomes: it could hurt more than it helps, with unintended paradoxical consequences.

Genuine innovations have long and complex histories, so systematically seeking to connect outcomes with inputs is surprisingly challenging. It is only in hindsight, for example, that we can clearly see the path from exploration to discovery to profit.

However, the Marsden Fund has been the key supporter of blue-sky research in New Zealand for thirty years, and this means for three decades we have been running a natural experiment into whether and how open-ended investigations can drive innovation. This long history means that – without having set out to do so – we can now detect links between inputs and outputs, more clearly than comparable nations.

For example, take a look at OpenStar, an Upper Hutt-based company seeking the holy grail of clean energy: fusion. There are probably 100 startups around the world hoping to build “warehouse scale” fusion devices (in contrast to massive, multi-billion dollar installations) that can confine plasma temperatures of 100 million degrees Celsius such that nuclear reactions can take place inside. You can read about their progress on CNN and in the Financial Times.

So far, OpenStar hasn’t achieved a working reactor (and neither has anyone else), but just being in the game is a win for New Zealand.

To be clear, OpenStar is not Marsden-funded. But their key advantage is based on New Zealand’s expertise in high-temperature superconductors – materials that conduct electricity without “friction” when cooled with liquid nitrogen (“high temperature” is a relative term here) instead of far more expensive liquid helium.1 Electromagnets built with these superconductors are giving OpenStar their edge – and crucially, this expertise was boosted by Marsden-funded research through the 1990s and 2000s.

Serious deep-tech innovations are multiyear efforts, but for shorter stories you could look at MaramaLabs, Liquium, or Advemto – all are on local “hot startup” lists, and all have Marsden-funded research at their heart. And there are many, many other examples along these lines.

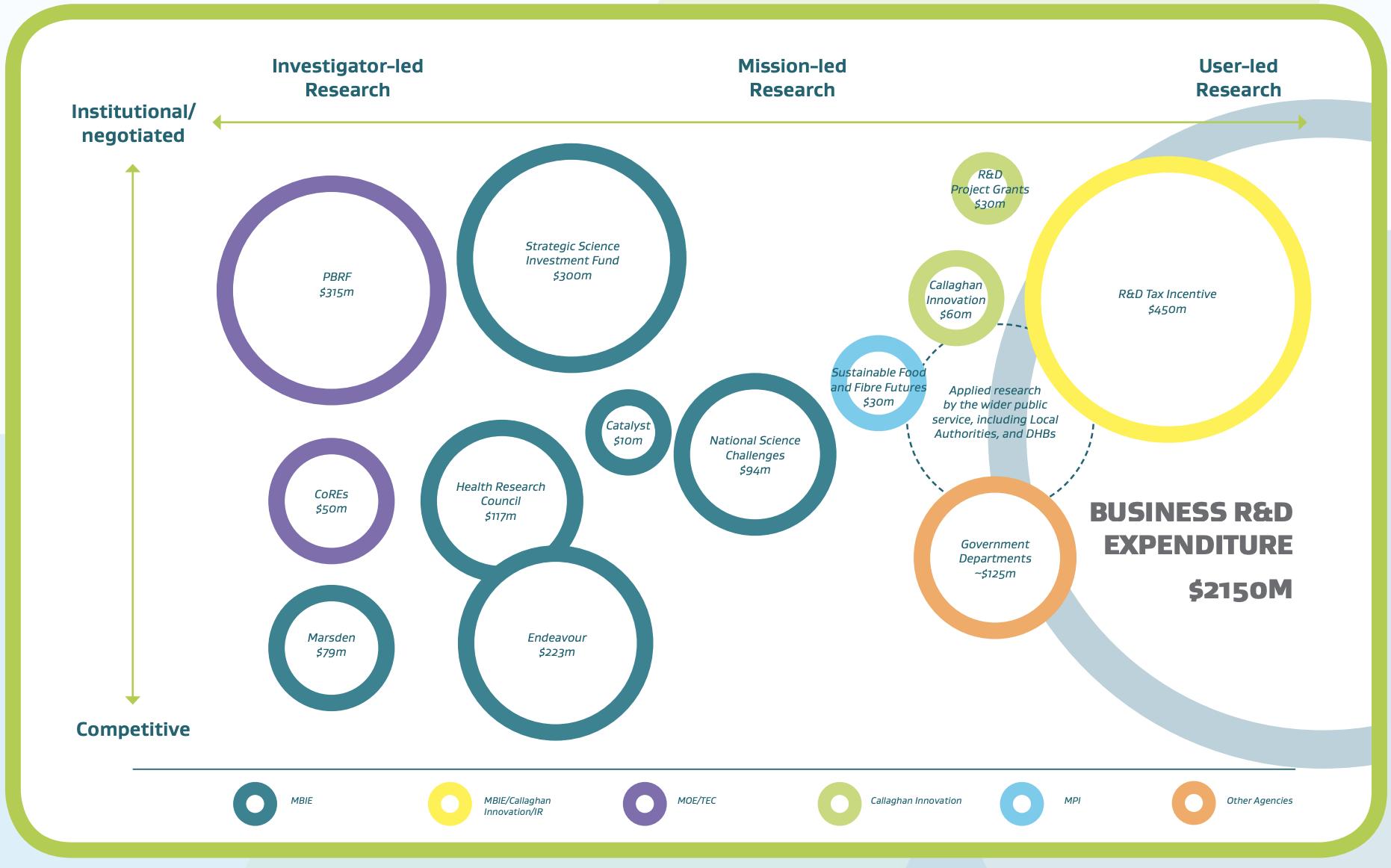

The paradox is that the Marsden Fund represents less than 5% of the overall research-funding pie, which is summarised in the diagram below.2 Consequently, you might expect to hear far more good news stories like these coming from the larger wedges that do require explicit economic outcomes. And those good news stories certainly exist – but the headline here is how much good work is being delivered by the small Marsden-shaped slice of the funding pie.

Some caveats on the above: I’ve focused on “hard tech” rather than software innovations; also, there are separate pools of support for biomedical research.

Marsden is often the spark for success stories that are then nurtured by other initiatives, such as the CoREs (Centres of Research Excellence, funded networks of researchers that provide long-term support and that deliberately bridge pure and applied science); the former Industrial Research Limited3 (which supported the superconductor development), and other pots of Crown money. Someone should do a truly quantitative analysis of the wider system; it would be fascinating.

The point is, many people in the system see that Marsden is unexpectedly good at producing economic benefits – or, the corollary may also be that the funds that actually explicitly target “outcomes” are weaker at producing them than we might hope.

My guess is that it is actually both of the above. It’s easy to assume that Marsden only supports abstract curiosity, and to then forget (or fail to see, in the case of a few voices who applauded this announcement) how often it leads to tangible benefits down the line. Conversely, it may be that tightly targeted funds risk squeezing out opportunities for the unanticipated outcomes that form the lifeblood of early-stage innovation.

Either way, if the Marsden Fund is being asked to pay more attention to economic outputs, the key challenge is going to be doing this without harming a goose that is already regularly laying golden eggs.

Beyond the immediate politics of this funding shakeup, New Zealand suffers from a longstanding timidity around risk and ambition in the science bureaucracy. MBIE, our “Ministry of Business Innovation and Enterprise” sometimes resembles a distant, wealthy relative who shows up only occasionally bearing gifts purchased with little real insight into who we actually are. Of course, nobody wants to appear ungrateful so we can often find ourselves maintaining polite public fictions about failed MBIE-initiated investments. And worse, in some cases a tight focus on strictly economic outcomes has actually created perverse incentives for substandard work.

As someone who often communicates with the public the ins and outs of complex science, I am fond of analogies and metaphors, and a handy one springs to mind here. Namely, I can’t escape the conclusion that government policy is already too focused on the fruits it imagines it might pick from the orchard of science, at the cost of the fundamental and ongoing health of the trees themselves. Currently, the Marsden Fund is one of the few sources of support that focuses on the sustainability and growth of the orchard as a whole, and which is dedicated to helping new seeds to take root and sprout.

So what’s the answer? I believe it would be far more healthy if government and the science community were to work together to set an ambitious overarching strategy, rather than having potentially counterproductive changes suddenly dropped on working scientists from a great height.4 Our current Minister does appear to have genuine enthusiasm for science; and given extra investment is a tough ask in the current climate, it is all the more important to disburse what we do have as effectively as we can.

Lastly, I am reminded of a story that scientists like to share. As the legend has it, Michael Faraday (or according to other sources, Benjamin Franklin) was showing a senior member of the government around the lab where he had teased out the profound connections between electricity and magnetism.5 The visitor, upon spotting an early electric motor spinning on its wobbly axis, asked: “But what use is this?”

And Faraday replied: “Sir, what use is a newborn baby? But one day you will tax it.”

- In fact, these magnets turn up in a range of innovations, from novel thrusters for spacecraft, to high-efficiency engines for electric aircraft, and novel MRI machines. ↩︎

- In terms of tracing impact, we are looking at past spending, rather than the present situation – however it should be noted this graphic is a little out of date as the National Science Challenges have since closed with nothing to replace them (which is a whole separate problem). ↩︎

- IRL morphed into Callaghan Innovation over ten years ago. Its name honours Paul Callaghan, who was a champion of New Zealand’s potential to benefit from research-driven tech. Ironically, one of the first things the new institute did was divest itself of its superconductor team along with many physical workshops – one of which once employed a young man named Peter Beck. ↩︎

- The suddenness of this proposed change is amplified by the fact that we are still waiting on the outcome of a much larger review of the “science system”, led by Sir Peter Gluckman. He has previously advocated for a separate science ministry, and I hope this comes to pass. ↩︎

- OK, I am an academic so I checked the details: Snopes confirms this is an urban legend. And yet, the story continues to circulate, freighted with a narrative truth that is hard to ignore. ↩︎

Disclosure: Needless to say (perhaps with more need than normal) these opinions are mine, not those of my employer. That said, this commentary undoubtedly contributes to my employer’s role as a “critic and conscience of society”, as required by the Education and Training Act. In the interests of even fuller disclosure, I have served a term on the Marsden Council, the governing body of the fund, and have received Marsden funding myself. In other words, I am familiar with the terrain of this orchard.

*Richard Easther is a professor at the Department of Physics, University of Auckland. He blogs at ExcursionSet, where this post first appeared, and runs a mailing list that people can join.

1 Comments

Knowledge is irrespective of money.

Indeed, if the irruption of humanity bent on wiping out its chances of ecological survival on this singular planet, is going to keep on myopically chasing $$$$$$$$$ - it's stuffed.

So the knowledge has to be gained, and maintained, in a way that doesn't stuff out ecological chances. I don't sense this person gets that.

He might like to do some homework - https://dothemath.ucsd.edu/post-index/

Being physics, he might just get there...

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.