This is a release from Auckland Council. It is here with permission.

2024 was challenging for many Auckland businesses and households, with high interest rates dampening spending and investment. Those rates were underpinned by the Official Cash Rate being held high for much of the year to reduce inflation. Reflecting on the data, here are five observations on Auckland’s economy.

Feeling the cycle

Nationally, economic activity contracted in mid-2024 and on some measures Auckland appeared more affected. Figure 1 shows card spending for the December quarter was down 4.1% in real terms on the prior year, compared to a 1.9% decline nationally. Employment in Auckland was down 20,000 or 2.0% lower, versus 1.4% nationally.

Auckland may be more sensitive to higher interest rates given its elevated house prices and household debt. Conversely, economic activity in Auckland tends to surge in an upturn, benefiting from its scale and international connectedness. Looking ahead, the recent interest rate cuts suggest a gradual pick-up in activity in 2025. This highlights how most public policy decisions to need look beyond near-term fluctuations and focus on trends.

2.Auckland is still growing

Auckland’s population grew by 44,600 people, or 2.5%, in the year to June 2024, according to Stats NZ. That increase is the second highest on record, as Figure 2 shows. It confirms the population has been growing again after the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A growing population increases demand for goods and services while also expanding the labour supply, which supports economic growth. However, population growth can also put pressure on infrastructure. This highlights the importance of effective policies for growth, including using pricing to get more from infrastructure networks and to incentivise efficient growth, allowing urban land to be used more productively, and prioritising spending towards projects with the best value for money.

3. Productivity questions remain

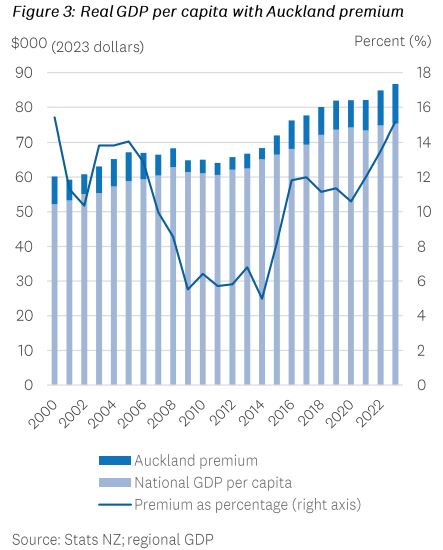

Auckland contributed $149 billion, or 38%, to national GDP in the year to March 2023, according to provisional data released in 2024. While GDP data has a lag and is subject to revision, it reveals trends in productivity – how much more is produced from our resources over time.

For instance, Auckland’s GDP per capita was $86,700, about 15% above the national average of $75,300. That premium reflects Auckland’s density and scale, which enable ease of access, knowledge sharing, business specialisation, and economies of scale in infrastructure.

Auckland’s GDP per capita premium has fluctuated and is now similar, in percentage terms, to what it was at the start of the century, as Figure 3 shows. However, primary cities in prosperous small-to-medium size economies typically have a premium that is a quarter to a third higher than their national average.[1] This raises the question of whether Auckland could be doing better.

New Zealand has had low productivity growth and addressing this is critical to improving living standards, as the Treasury has noted.[2] Reasons for this may include a small domestic market, low capital intensity, the slow diffusion of innovation, low savings and a high exchange rate. Auckland’s performance also requires attention, as a boost to national productivity seems unlikely unless Auckland improves too.

The government is responsible for key policies on human capability, the business environment, and international connections. Auckland Council’s land use and transport policy settings also affect productivity by shaping where households and businesses can locate, and how people and goods can move around. This highlights the need for decisions on these policy settings to be informed by advice on their productivity implications.

4. Competing for skills

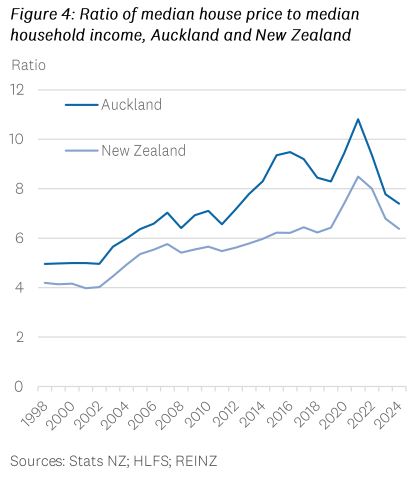

Cities compete to attract and retain people, businesses and investment. Income levels and housing costs are key to retaining and attracting skilled people, along with urban and natural amenities. As such, the affordability of housing matters for Auckland’s competitiveness.

In 2024, Auckland’s ratio of median house price to median household income was 7.5 whereas the national ratio was 6.4, as Figure 4 shows. The gap has closed a bit since 2016 when Auckland’s ratio was 9.5, or 50% above the national ratio of 6.2. Even so, if Auckland still had a ratio of 5 – as it had in 2000 – the median price would be around $680,000 instead of $1 million.

Auckland’s relatively poor housing affordability makes it harder to retain skilled people. While Auckland is growing, due to international migration, there are large international outflows and an annual net loss to other regions averaging 10,000 people in recent years.

Improving housing affordability is key to retaining more skilled people, especially mobile young people. It will require land-use policies to enable more flexible use of urban land, to allow more homes – and more choice – in high-demand locations near jobs and transport options.

5. The rise of remote working

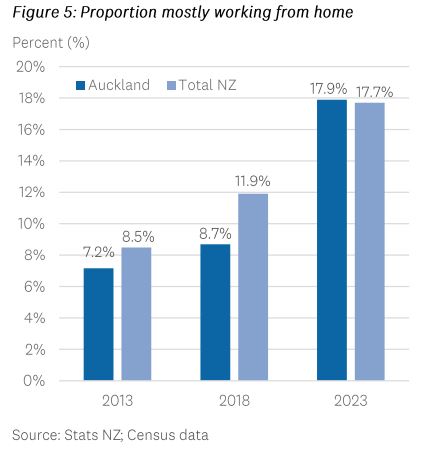

The uptake of remote working sped up with the COVID-19 pandemic. Census data released in 2024 shows 17.9% of workers in Auckland mostly worked from home in 2023, double the 8.7% seen in 2018, as Figure 5 shows.

The option to work from home can reduce travel time and cost for workers and improve work-life balance and job satisfaction. Businesses with hybrid working models may be able to reduce their floor area. However, shifts in where work is performed can alter spending patterns and affect businesses that rely on worker patronage.

The outlook for remote working will depend on whether it suits both businesses and workers. Not all roles can be done remotely, and businesses must prioritise their productivity. Still, lowering the cost of accessing work may support labour force participation, skill retention, and productivity. Any further shifts are likely to be gradual and occur within a growing population, which suggests the role for policy is one of ongoing monitoring.

Take-aways

Auckland was affected by the downturn in 2024. The population grew, despite a net loss to other regions. Poor housing affordability continues to hinder retention and attraction of skills. While relatively productive nationally, Auckland’s GDP premium is still lower than other primary cities, suggesting scope to improve. The rise in remote working may reduce the cost of accessing work.

Of these issues, the challenges of population growth, poor housing affordability and low productivity are interrelated and amenable to policy responses. Allowing more flexible use of existing urban land, using pricing to get more from infrastructure networks and to incentivise efficient growth, and prioritising on the basis of best value for money would all lead to better outcomes.

[1] A sample comprising: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, South Korea, Norway, and Sweden

[2] ‘The productivity slowdown: implications for the Treasury’s forecasts and projections’ New Zealand Treasury Paper, 2024;

* Gary Blick is the Chief Economist at Auckland Council. This article is here with permission. The original is here.

1 Comments

Is it politic to use of a photo of the Auckland Container Terminal, given the failure of the automation project and associated 65 million dollar+ write-off?

Or am I missing the irony?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.