Last week I discussed the suggestion from the Minister of Finance, Nicola Willis, that a cut in the corporate tax rate from 28% was under consideration.

Subsequently, on last Sunday’s Q+A, Robin Oliver was interviewed by Jack Tame on the topic. Robin is a former Deputy Commissioner of Policy at Inland Revenue and was also a member of the last Tax Working Group. In his role as a Deputy Commissioner at Inland Revenue he would have been involved in most of the major tax reforms of the last 30 years, so he really is one of the Titans of tax and always worth listening to.

Go big or go home…

In discussing the question of a corporate tax cut he made a very important point - go big or don't bother. In his view dropping it from 28% to 25% simply wouldn't make much difference. Instead, he suggested a bolder approach would be to cut it to say 18%. Because if you really are wanting to attract investment then you have to show something significantly different.

He raised the point that Singapore, which is often raised as a comparable, has a 17% corporate tax rate. Ireland, another comparable country has a 12.5% rate. Against these countries we would need to cut our tax rate substantially in order to attract investment.

But Robin Oliver also raised the question as to the consequences of such a cut and whether there might be other opportunities for improvement. He mentioned the problems which we've previously discussed about the Foreign Investment Fund regime. He also floated the alternative of accelerated depreciation for plant and machinery, which in his view was more fiscally realistic. Personally, I think this would be a more worthwhile move.

Reshaping our tax system – higher GST?

If he was given the opportunity for complete freedom of action over the tax system, Robin Oliver would be bold and go for higher GST rate and taking the emphasis away from income tax. But he pointed out that although this might be nice in theory, the GST rate might have to rise to 28%, which would be pretty near unacceptable to the broader public. His key point was there are trade-offs to be to be made and it's not simply a matter of a corporate tax cut will attract investment. Other considerations have to come into play.

I agree with Robin that if you are going to go with a corporate tax cut, you probably have to be bold about it. The question then is how do you recover that lost revenue? Robin’s response was that some hard choices would have to be made. He was a bit gloomy on those options, I thought.

What about a capital gains tax?

As I said Robin is a vastly experienced tax practitioner and he would have considered many options during his time supporting the work of various tax working groups and then as part of the last tax working group. He made a passing comment suggesting people stop whinging about capital gains tax. Robin was one of the three dissenters to the general capital gains tax proposal made by the last Tax Working Group but remember that the whole group was unanimously supportive of increasing the taxation of residential investment property.

Overall, very interesting to hear Robin’s take and I recommend watching the interview. It may be a corporate tax cut needed to be really attractive is probably beyond the Government’s fiscal capabilities at this point and therefore other alternatives might be more cost effective.

Further clues about tax changes?

Incidentally Iain Rennie, Secretary to the Treasury, made a speech to the 2025 New Zealand Economics Forum Bending two curves: New Zealand’s intertwined economic and fiscal challenges which supported a speech made by Finance Minister Nicola Willis, yesterday about the Government’s Going for Growth economic plan. Both mentioned tax with Iain Rennie noting

Our taxation of investment is also uneven, which distorts investment choices. Such economic settings can discourage the acquisition of productivity-enhancing assets like machinery and equipment.

This suggests that the policy responses are likely to include those that create an environment more conducive to firms making these investments. This could be through the structure of business taxation, savings policy, and regulatory frameworks that keep pace with business changes and create certainty for investment in emerging sectors.

These speeches provide a few more that a corporate tax cut could be perhaps a possibility. But there are, as Robin Oliver pointed out, other opportunities. Anyway, we’re obviously going to see a lot more speculation in the run up to the Budget on 22nd May.

Netflix’s tax reporting under investigation in France

An interesting story popped up this week involved Netflix’s tax activities. It appears Netflix's offices in both Paris and Amsterdam had been raided late last year by French fraud investigators. European Union investigators started looking into the matter after France’s National Financial Prosecutor's Office raised suspicions about the company “covering up serious tax fraud and off-the-books work”.

It transpires Netflix's French subsidiary reported turnover “at odds with paying user numbers in the country.” Between 2019 and 2020, Netflix France paid less than €1,000,000 in corporate taxes, despite having more than 10 million customers.

What about Netflix New Zealand?

This is an ongoing investigation which after it came to the attention of Edward Miller the researcher at the Centre for International Corporate Tax and Accountability and Research, piqued his interest about Netflix’s activities here. When he went looking, he found out Netflix does not file any financial statements in New Zealand. This is actually acceptable under our low compliance approach to corporate filings. At present under the Companies Act 1993 public financial statements of a foreign-owned company must be filed if either the total assets are more than $22 million or the total revenue exceeds $11 million.

Now, surprise, surprise, Netflix New Zealand Ltd is apparently falls below that threshold, which as Edward Miller pointed out, seems odd given that there's about 1.3 million users in New Zealand paying at least $18.49 a month to access its service. We're therefore looking at another example of how multinationals are apparently able to shift profits offshore. Simultaneously, this is also an example of how tax authorities are increasingly taking a look at these activities and saying, ‘well, this is no longer really acceptable in our view.’

What do Netflix and Uber have in common?

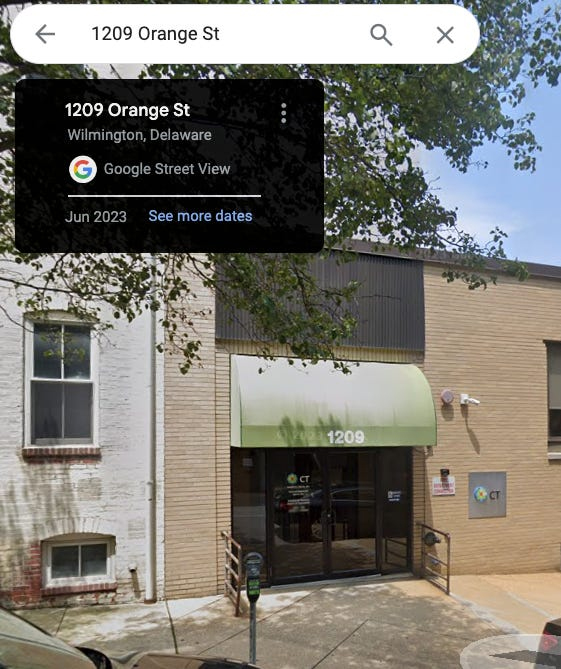

Where it becomes quite entertaining is that ultimately the head office for Netflix appears to be an address in a very unassuming building at 1209 Orange St, . Wilmington, Delaware in the United States. Delaware is a very tax favourable jurisdiction within the United States, and this particular address is so favourable that it is registered address of no fewer than 285,000 U.S. companies, including Uber.

That somewhere so modest is the home to so many companies is entertaining but also points to the serious issue of highly sophisticated tax planning where apparently income is earned in a jurisdiction but little or no income tax is paid.

In fairness to Netflix, notwithstanding its income tax position, it's highly likely that it will be paying a substantial amount of GST. That's because its customer base is individuals who will not be GST registered and therefore will not be able to recover the GST paid.

Incidentally, Visa and Mastercard are two other companies that we know very little about but have a significant effect here. Neither company have published financial statements for almost 10 years now. The revenue they earn on fees probably runs to hundreds of millions of dollars, but we just don’t know what portion is being taxed here. What Netflix is doing is a bigger issue than perhaps is generally appreciated.

Time to rethink our reporting requirements?

Given how opaque these transactions are, perhaps we need to rethink our rather relaxed approach to reporting and filing of a company’s financial statements, particularly in relation to multinationals. Interestingly, Australia now requires large multinational groups with an Australian presence to submit data on their global financial and tax footprint to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), which will give more disclosure where around international profits are being booked. The Post approached the Minister of Revenue, Simon Watts, for comment and said that a similar proposal was not under consideration. (Note that the Australian proposal goes beyond country-by-country reporting https://www.ird.govt.nz/international-tax/exchange-of-information/count… which applies to a small number of multinationals).

What next?

The French investigation of Netflix is just another example of how many tax authorities around the world are looking at this question of where's that income being really taxed and wanting justification for enormous fees that seem to end up in tax havens. But then, as I said last week, we now have the potential threat of the United States under the new Trump administration not favouring such investigation activities. It will be interesting to see how this plays out.

Are repairs to a newly acquired asset deductible?

As always, Inland Revenue is busy producing guidance on a number of matters and this week it was an exposure draft (ED) on a very interesting point – are expenses incurred on repairing a recently acquired capital asset deductible.

This draft is part of a series on repairs and maintenance expenditure which will eventually replace the current Interpretation Statement IS 12/03 - Deductibility of repairs and maintenance expenditure - general principles.

This exposure draft is potentially pretty significant – it reaches a different conclusion from IS 12/03 on the relevance of whether the price of the asset was discounted. Consequently, Inland Revenue is “particularly interested in comments on the relevance of the assets price in the context of initial repairs, as it appears there may be differences in opinion and practice.”

The ED guidance centres on what happens if you buy an asset that's pretty run down, and then you carry out repairs to it to get it up and running? Are you able to claim those costs as repairs or should they be capitalised? For example, if you buy machinery that's pretty run down and carry out repairs. If you can't show that the repairs are genuine repairs - that they reflect wear and tear - Inland Revenue’s view is you must capitalise those costs. As such those costs are probably going to be depreciable.

What about repairs to buildings?

However, it’s a much, much bigger issue in relation to buildings. Because with the withdrawal of depreciation allowances for all buildings (not just residential buildings) the question of whether expenditure represents repairs and maintenance becomes an all or nothing issue. In other words, if it's a repair, it's deductible. If not, no deduction, whether in the form of depreciation or any other form, is available. I see a real pressure point emerging on this matter.

As always there's lots of useful examples, but there's also one or two matters we'd like to see clarified. For example, the ED refers to “normal wear and tear.” But what does that mean? If you're talking about an asset that's depreciated over, say, five years economically are Inland Revenue saying that repairs in excess of what the normal depreciation would be on that asset must be capitalised?

What about buildings?

It's something I think needs more certainty, particularly in relation to buildings. The ED has an example on the treatment of repairs to a newly acquired building and I'm not so sure I'd agree with Inland Revenue’s conclusions. In summary, a 100-year-old tenanted residential property has been inherited by James. It's in a poor state of repair and its condition was such that it could only be rented on a short-term basis with a high turnover of tenants and poor rental returns.

Because the property is in a good location James therefore decides if he restores the property to good condition the rental return can be increased by attracting different tenants for longer term letting. So, he carries out repairs to the property while it remains tenanted, including repairing the leaking roof, replacing some of the guttering down pipes, repainting portions of the exterior proper, and a number of other matters, including a repair to the main water supply pipe to the property.

The conclusion is that the expenditure incurred was necessary to restore and maintain the functionality of the property to the level required for its intended use of letting it on a longer-term basis. And for that reason, it's capital in nature. No deduction will be available, and as I mentioned earlier, because it's a building, no depreciation is available.

I'm not sure that would stand up in court if tested, because James is still deriving gross income. Yes, there's an improvement to enhance it, but court cases have accepted that all repairs involve some form of improvement because you're replacing old materials with new materials.

I'm intrigued to see what the response is to this and what comes out in the finalised guidance. Certainly, as I saw Robyn Walker of Deloitte point out buying a car without and then claiming a repair by sticking wheels is clearly something that is not appropriate. But then in that case there should be a depreciation deduction available. It’s much more tricky in relation to repairs carried out to newly acquired properties. Again, watch this space.

And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day

4 Comments

Taxation as a percentage of gross revenue for companies and corporates?

For foreign owned ones yeah.

It is frustrating to me that 'tax experts' never take the opportunity to talk up land taxes, as the most economically efficient way of raising government revenue, but I suppose they are accountants not economists so perhaps it isn't quite as glaringly obvious to them.

Corporate tax rate -> 18%

GST -> 20%

Land tax -> ~1%

\The last two will produce more income than the corporate tax rate reduction. With what's left over, fund some combination of:

Income tax reductions -> especially at the bottom to improve equity and reduce the impact of abatement rates. Could also do work here to increase efficiency by reducing some benefits at the same time.

R&D tax credits to encourage innovative investment

Reduced/no tax on NZ denominated assets held in kiwisaver to build retirement balances more quickly (solving long term political issue of means testing super, heck could announce the two together and say 'super will be means tested from 2035 to give people time to prepare'). It's nice because it also does nation building, and would increase liquidity in our financial markets meaning our successful businesses are less likely to primarily look for capital (and eventually move the highest paying jobs) offshore.

Am I reading correctly that you're suggesting cranking the rate of GST up over 20%?

Without putting my big thinking cap on here, this will significantly impact the poor, who will not be able to avoid it. So that will likely increase the welfare burden on other taxpayers, who probably won't appreciate it (on top of te 20%+ rate of GST they are also incurring).

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.