This week the ninth edition of the OECD’s Tax Policy Reforms was released. This is an annual publication that provides comparative information on tax reforms across countries and tracks policy developments over time. This edition covers tax reforms in 2023 for the 90 member jurisdictions of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting.

Reversing the trend

It's a fascinating document which tracks trends of what's happening around the tax world at both a macro and micro level. The report has three parts: a macroeconomic background, then a tax revenue context, and then part three is the guts of the report with details of tax policy reforms around the world.

There is an enormous amount in here to consider and the executive summary lays out the ‘balancing act’ issues pretty clearly

“Policymakers are tasked with raising additional domestic resources while simultaneously extending or enhancing tax relief to alleviate the cost-of-living crisis… On the one hand, governments further protected and broadened their domestic tax bases, increased rates, or phased out existing tax relief. On the other hand, reforms also kept or expanded personal income tax relief to households, temporary VAT [GST] reductions, or cuts to environmentally related excise taxes.”

A key observation for 2023 is there was a trend towards reversing the responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, Instead, as the report notes “2023 has seen a relative decrease in rate cuts and base narrowing measures in in favour of rate increases and base broadening initiatives across most tax types.”

“A notable shift”

This includes “A notable shift occurred in the taxation of business, where the trend in corporate income tax rate cuts seems to have halted with far more jurisdictions implementing rate increases than decreases for the first time since the first edition of the Tax Policy Reforms report in 2015.”

This is a pretty significant change. I think actually when you consider last week's speech by Dominick Stephens of Treasury, it was setting out the context for why having got over the crisis of responding to the pandemic, countries are realising they've got to deal with the demographic issues of ageing populations and funding superannuation.

Climate considerations

Beyond these concerns, there is the immediate impact of climate change and its growing effects. The executive summary picks up on this issue:

“Climate considerations are also increasingly influencing the design and use of tax incentives, with more jurisdictions implementing generous base narrowing measures to promote clean investments and facilitate the transition towards less carbon intensive capital.”

And on that point, I hope all the listeners and readers down in Dunedin and Otago are safe and well at the moment.

Paying for superannuation

What's the other thing is picked up is that in rate referencing that point I made a few minutes ago about population ageing. There has been a growing trend amongst countries to broaden increase Social Security contribution taxes. Alongside Australia, and to a lesser extent Denmark, we are unique in that we don't have social security contributions. However, elsewhere in the OECD social security contributions raise increasingly significant amounts of revenue.

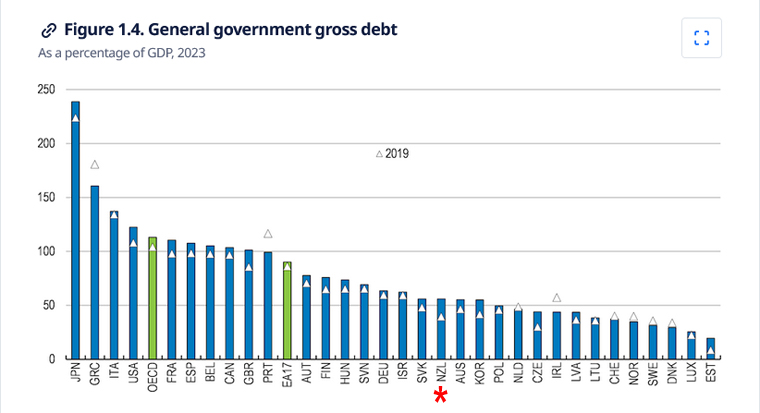

The report begins with a macroeconomic background. It notes that for the OECD as a whole in 2023 government debt rose by about nine percentage points, reaching 113% of GDP. For context, New Zealand’s debt-to-GDP ratio is just over 50%.

As the macroeconomic summary notes after generally decreasing in 2022 Government deficits increased again in 2023 following the energy crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine. Consequently,

“As debts and interest rates increased, interest payments have started to rise as a share of GDP. Even so, in 2023 they mostly remained below the average over 2010 to 2019, except notably for Australia, Hungary, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.”

In short, we definitely have issues to deal with in terms of debt management and rising costs.

Responding to growing deficits

The report then notes that responses to growing deficits have been to start at increasing taxes. In general tax revenue terms,

“From 2020 to 2021, the tax-to-GDP ratio rose in 85 economies with available data for 2021, fell in 38, and stayed the same in one. In more than half of these economies, the change in the tax-to-GDP ratio was under one percentage point, whereas 22 economies saw shifts greater than two percentage points in their tax-to-GDP ratio.”

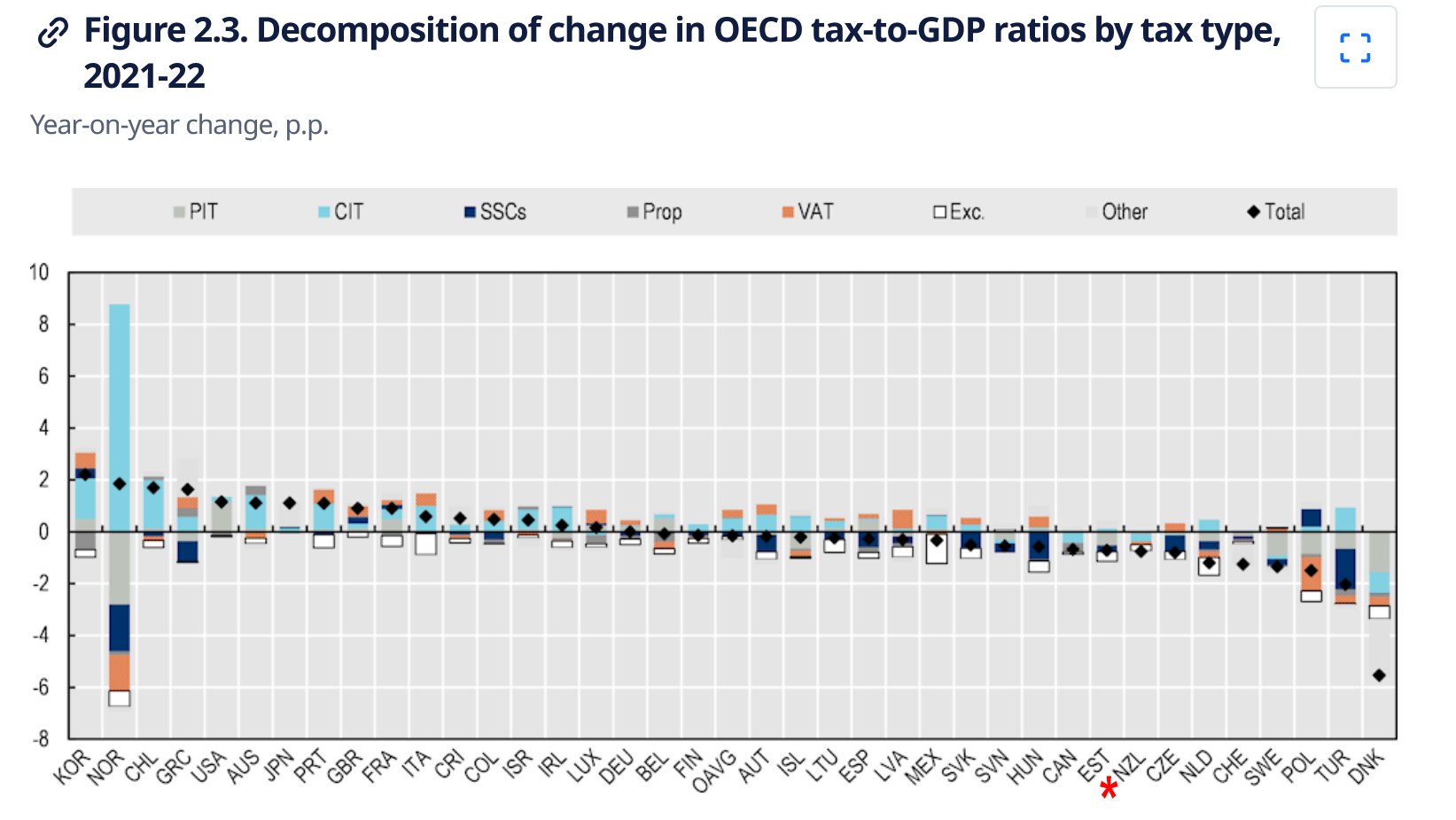

Denmark saw the most significant drop of 5.5 percentage points, with New Zealand’s tax-to-GDP ratio falling by three-quarters of a percentage point, well above the OECD average fall of .147 percentage points. (Norway’s dramatic corporate income tax take increase of 8.775% is the result of “extraordinary profits in the energy sector”.)

Composition of tax base

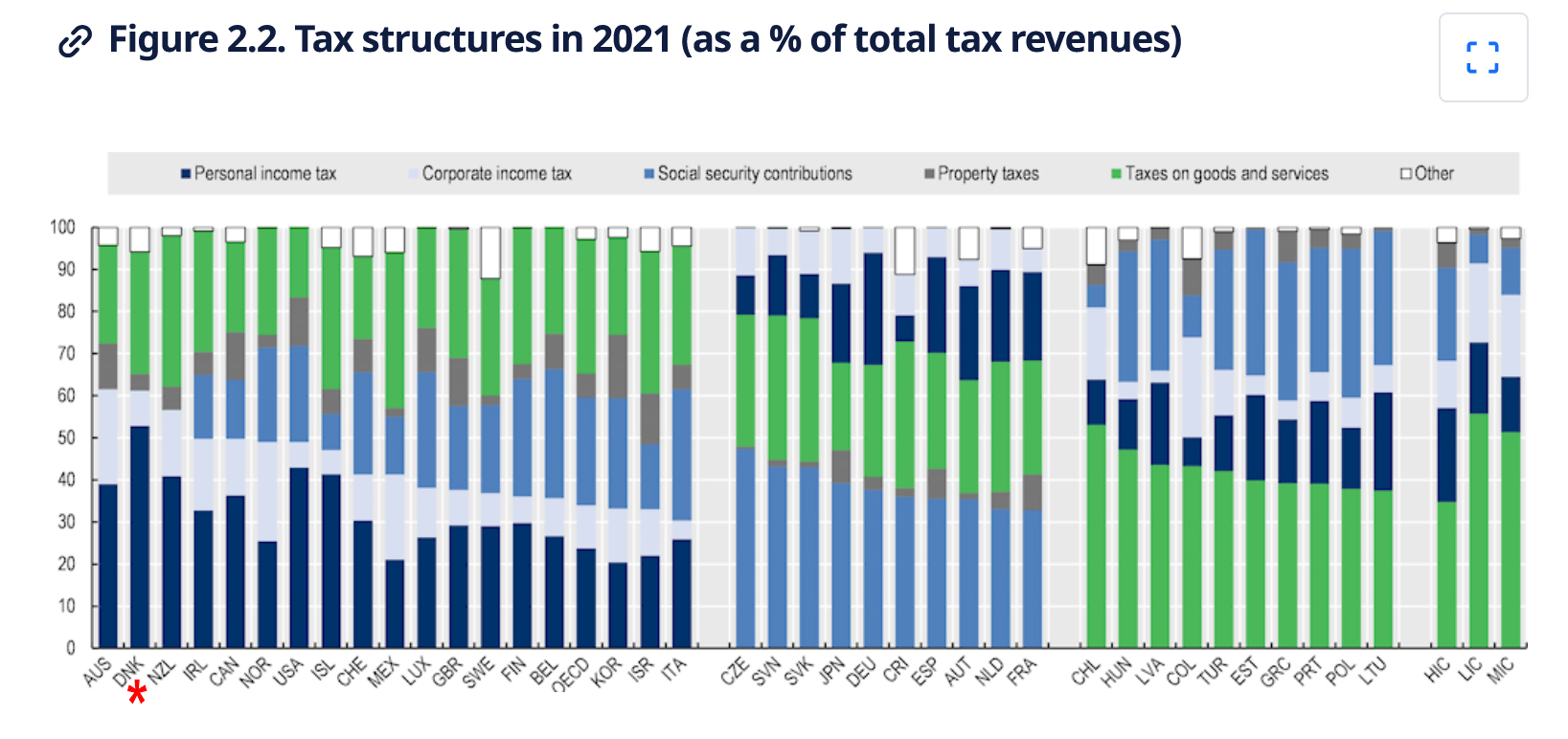

With regards to the composition of tax 18 OECD countries (including New Zealand) primarily generate their revenues from income taxes, including both corporate and personal taxes. 10 OECD countries relied most heavily on Social Security contributions, and another 10 derived the majority of the revenues from consumption taxes, including VAT, (GST). Notably, taxes on property and payroll taxes contributed less significantly to the overall tax revenue mix in OECD countries during 2021.

Drilling into the detail

Part 3, of the report looks at the detail of the tax policy reforms adopted during 2023. This part has an introduction, then looks at five separate categories of taxes beginning with personal income tax and Social Security contributions, followed by corporate income tax and other corporate taxes, taxes on goods and services, environmentally related taxes and finally taxes on property.

As I mentioned previously, there was “a marked increase in the number of jurisdictions that broadened their Social Security contribution bases and raised rates”. Generally speaking, for high income countries personal income tax and social security contributions represent 49% of total tax revenue. Across the OECD personal income tax represented 24% and social security contributions 26% on average.

Here about 40% of all tax revenue comes from personal income tax. That's one of the higher proportions around. Around the globe there was a bit of tinkering around personal income tax reforms mainly targeting lower income earners. This is an area where I think we need to focus any future reforms.

We have just (partly) adjusted thresholds for inflation and interestingly, I see that during 2023 quite a few jurisdictions did increase thresholds for inflation. For example, Austria updated its automatic inflation adjustment mechanism to counteract inflation, pushing workers into higher brackets. Meanwhile Australia increased its threshold for its Medicare levy to ensure low income households continue to be exempt, given that inflation has led to higher normal wages.

Corporate income tax rates are on the rise

Substantially more rate corporate income tax rate increases and decreases were announced or legislated by jurisdictions in 2023. Six jurisdictions increased their corporate tax with four of those did so by at least two percentage points. Türkiye increased all its corporate tax rates by five percentage points.

Whenever there are discussions about reforming our tax system, the issue of reducing our corporate tax rates will come up. With a 28% rate we are at the higher end of the corporate tax rate scale. There is potentially some scope, but as economist Cameron Bagrie has noted any such decrease needs to be part of a broader range of changes.

An example of such a change was the introduction of a general capital gains tax by Malaysia for all companies, limited liability partnerships, cooperatives and trusts from 2024.

Picking out of the details something which I know businesses here would look at with a certain amount of envy is more generous depreciation allowances. The UK, for example, has permanent full expensing for main rate capital assets as it's called and a 50% first year allowance for special rate assets. Australia has also increased its thresholds for effectively fully expensing items for small businesses. Around the world there’s a whole range of incentives for R&D and environmental initiatives.

We have just limited the limits for residential interest deductions but it’s interesting to see that Italy abolished its allowance for corporate equity provision. Meantime Canada has new restrictions on net interest and financing expenditure claimed by companies and trusts.

Taxes on goods and services (VAT/GST)

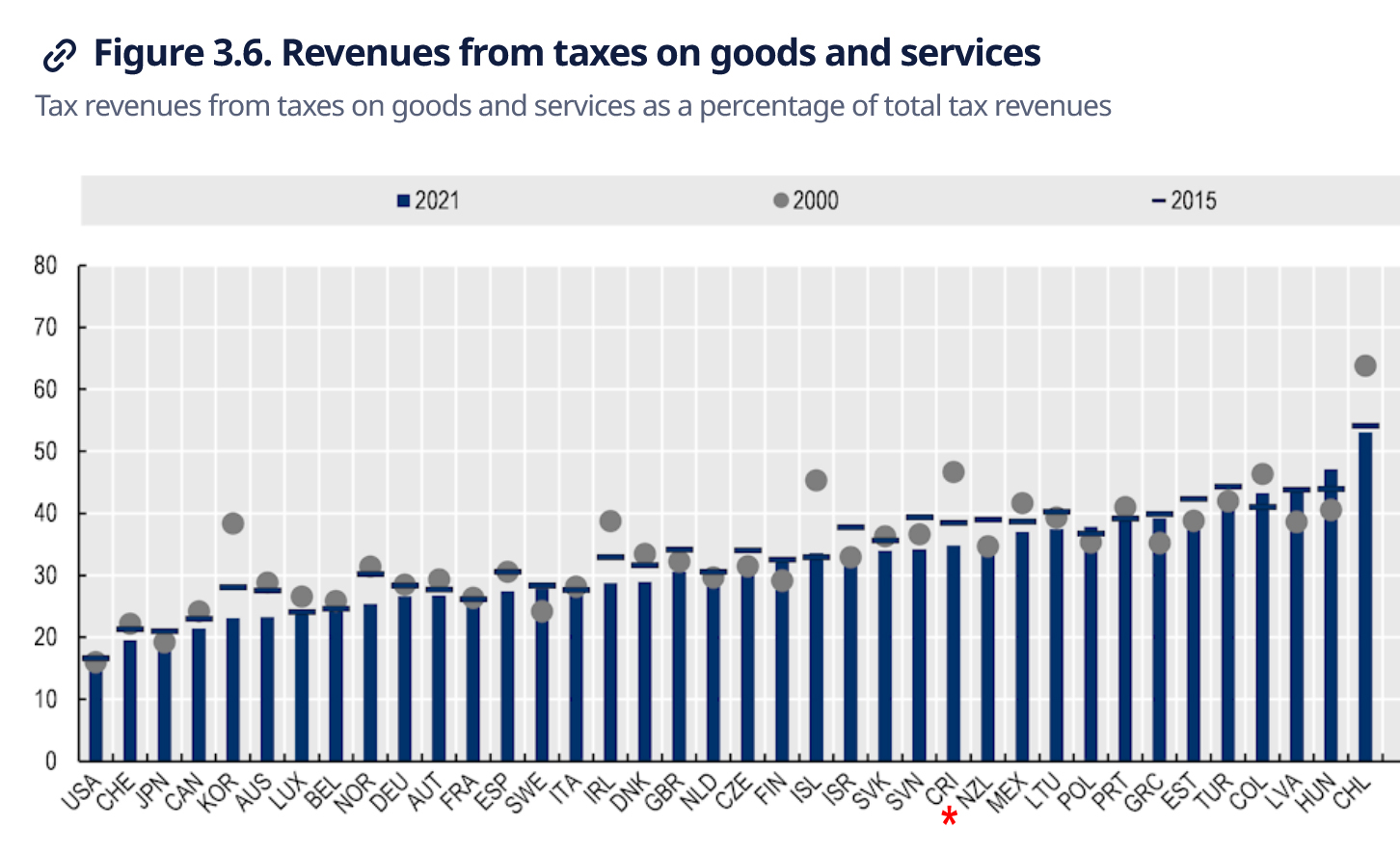

In the VAT/GST space, in terms of revenue from taxes on goods, although we have one of the most comprehensive GST systems in the world, New Zealand was only twelfth in the OECD for the percentage of tax revenue from goods and services as a percentage of total tax revenues. GST raises just over 30% of total tax revenue here, whereas Chile raises over 50%. This is quite interesting given how comprehensive our GST system is. It might mean that there is scope to expand the the rates of GST further. (Six countries including Estonia, Switzerland and Türkiye did so in 2023). But any government doing so should do so as part of a total tax switch package.

We discussed GST registration thresholds a couple of weeks back. During 2023 seven countries increased or planned to increase their VAT registration threshold. I was very interested to discover that Ireland has a split VAT registration threshold treatment: the registration threshold for the sale of goods is €80,000. But for the provision of services, it’s €40,000. I've not seen this split before. Meanwhile Brazil is undertaking the introduction of VAT/GST, which is a huge step forward.

A stable tax policy or just less tax activism?

There’s a lot to consider in this report more than can be easily covered here. Overall, it’s incredibly interesting to see what's going on around the world. Many of the reforms discussed here involve threshold adjustments but there are plenty of new exemptions and incentives introduced. We generally don't get into this space, that's possibly a reflection of a very stable tax policy environment, but also perhaps a less activist philosophy by New Zealand governments which hope market incentives will work. Whatever, the approaches it's interesting to see what's going on around the world and I recommend having a look at this very interesting report.

ACC crackdown

Moving on, ACC has been in the news when it emerged that it has been chasing thousands of New Zealanders for levies on income they earned while working overseas.

According to the RNZ report, ACC sent 4,300 Levy invoices for the 2023 tax year to New Zealand tax residents who had declared foreign employment or service income in their tax return. The issue is that the person was often overseas at the time the income was earned. overseas and in some cases the the person has probably incorrectly reported the income in their return.

It's an interesting issue and coincidentally, it so happens that I've just come across a couple of similar instances. My initial view is there seems to a bit of a mismatch between the relevant income tax legislation and the legislation within the Accident Compensation Act 2001. Watch this space on this one because I'm not sure the matter is entirely as cut and dried as ACC considers.

Inland Revenue responds to social media criticisms

A couple of weeks back, we covered criticism of Inland Revenue for providing the details of hundreds and thousands of taxpayers to social media platforms. It had done so as part of various marketing campaigns targeting people who owed taxes and Student Loan debt in particular.

Inland Revenue has now responded by putting up a dedicated page on its website, talking about referring to custom audience lists.

In its words “social media is just one channel we use to reach customers. It is very effective at reaching people where they are.” As I said in the podcast Inland Revenue’s dilemma is it has to go to where the people are which is on the social media websites. In order to reach out to them it’s going to have to provide certain data. To reassure people the new page explains how it uses custom audience lists and what data is provided.

They do upload a list of identifiers such as name and e-mail addresses, which is then ‘hashed’ within Inland Revenue’s browser before being uploaded to the social media platform. This is where I think the tech specialists have raised concerns that the hash technique is not as secure as Inland Revenue thinks.

Australia – the Lucky Country again

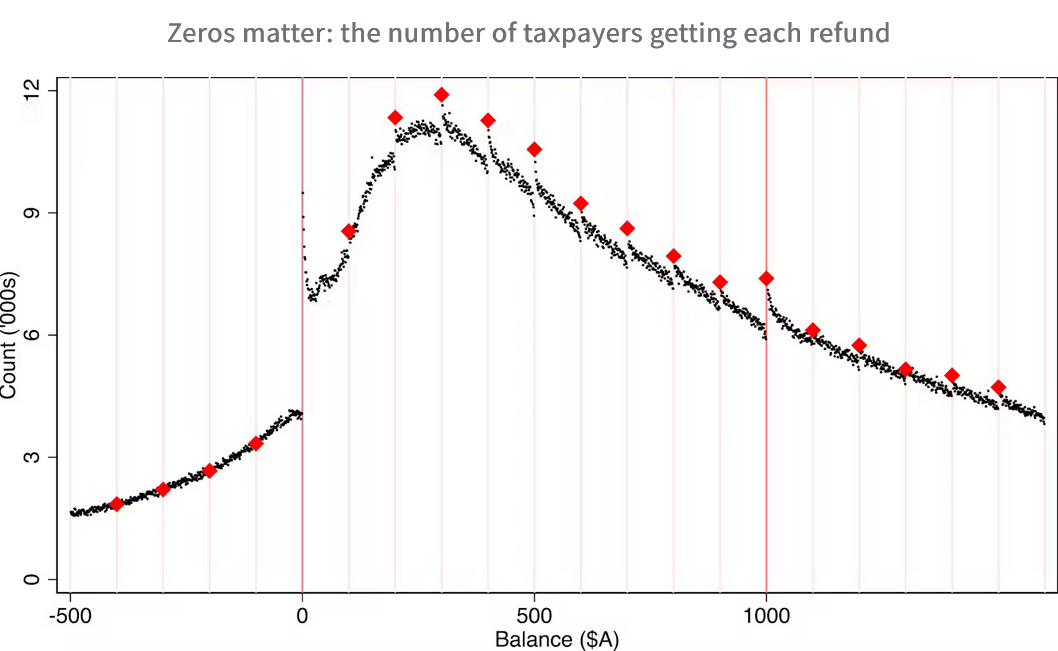

And finally, an interesting story from Australia about tax refunds. A research team at the Australian National University’s Tax and Transfer Policy Institute discovered a “striking” number of returns generating round number refunds (basically any digit ending in zero). The unit examined 27 years of de-identified individual tax files and found far more refunds of exactly $1,000 than of $999 or $995.

The unit concluded these returns are more likely to be driven by efforts to evade and minimise tax and are costly for the Australian Tax Office to audit such as work related expense deductions. Unlike New Zealanders, Australians can claim deductions on their tax returns. Somewhat concerning to me as a professional is that zeros in tax returns prepared by agents were twice as common as those prepared by taxpayers.

What this article is driving at is that some of the complexity of the Australian system results in the system getting gamed. Back in February you may recall Tracey Lloyd, Service Leader, Compliance Strategy and Innovation at Inland Revenue was a guest on the podcast. Based on our discussion and my own observation I would have confidence that Inland Revenue would not get caught out the same way thanks to the Business Transformation programme. As Tracy recounted, Inland Revenue can track live changes and they can see people just trying to square the return off to what they regard as an acceptable number.

Anyway, it's an interesting story. It shows the differences between our tax system and that of Australia, but it does seem a little rich that not only can you earn more in Australia, but you get bigger refunds.

And on that note, that's all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.

5 Comments

As a proportion of GDP, taxes in New Zealand are greater than in Australia. But of course, the Left thinks that the government always needs more tax, and would like the government to control everything including the private economy. That worked just great in Venezuela.

People often point to Australia and go "oh they have a 45% top tax rate, so rich people are better off in NZ". This is not true. The Australian tax system has a myriad of ways to reduce or eliminate personal income tax. For example:

- losses on investment properties can be offset against personal income. This is why 42% of surgeons own investment properties.

- corporate franking credits available to taxpayers on <30% tax rates are returned as cash not carried forward tax credits.

- salary sacrificing of things like car payments, superannuation contributions, meals, mortgage payments. An Australian healthcare professional gets their first $30k tax free due to the tax free threshold plus standard industry salary sacrifice benefits, more if their employer offers additional salary sacrifice benefits.

- use of a self managed super fund to hold investments (including property) where income is taxed at 15% and capital gains is 10%. This is great in combination with the cash refund of corporate franking credits. All becomes tax free once the beneficiary reaches the age of 60.

- superannuation contributions, concessionary taxed up to $30,000 a year, or non-concessionary up to $120k. Plus things like being able to sell your house if you are over 55 and put $300k ech into super so that income earned on it becomes tax free at 60.

NZ needs to ask itself, does it want a complicated tax system like Australia? Because it can't just raise taxes on people and think that not providing tax rebates or deductions is acceptable. Labour did that - removed interest deductibility on rental properties "like the UK" without acknowledging that the UK replaced interest deductibility with a corresponding finance cost tax credit. So no surprises when NZ's rental market fell apart and an extra 30,000 families ended up on the public housing waitlist. Taxes have consequences.

"- losses on investment properties can be offset against personal income. This is why 42% of surgeons own investment properties."

Isn't that ring fenced now? I seem to recall they did that years ago.

NZ did it a few years ago but not Aus as far as I know.

It's a current hot topic in Aus right now:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-10-01/house-prices-rise-investors-nega…

Nope. They are talking about it but the last 2 times Labor went to an election on it they lost. The only people who love property more than Kiwi's are Australians. Especially since most people buy an investment property before they buy their own home - courtesy of the fact that you can get FHB grants and stamp duty exemptions for the property, live in it for six months, then rent it out and get a 6 year exemption from capital gains tax, making it a tax advantaged saving scheme for your own eventual home.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.