By David Skilling*

Move fast & break things: central bank edition

Since the start of 2022, US policy rates have increased by 450bp, in the Eurozone by 300bp, in the UK by 390bp, and in New Zealand by 400bp. This speed and materiality of increase exceeds that in the years prior to the global financial crisis.

So far, most advanced economies have largely taken this in their stride. GDP growth rates and labour markets have been resilient, even if some interest rate sensitive sectors (like real estate) have weakened. But we may be reaching a point where things begin to break.

This would not be surprising. Public and private sector debt levels are at very high levels across advanced economies, and growth models of firms and countries have been deeply shaped by the low interest rate environment of the past 15 years. Our 2023 outlook noted that ‘The persistently expensive cost of money will provoke and discover many macro risks’.

Indeed, the blow-up of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) may be appropriate given that the VC sector benefited disproportionately from easy money over the past decade. It is striking that SVB’s share price had shrunk by almost 2/3 in the 15 months before last week, in tight correlation with an increasing 10 year government bond yield. SVB’s particular issues were idiosyncratic, as are Credit Suisse’s, but more interest rate-related stresses will emerge across the financial system and beyond.

Trade-offs between inflation, financial stability, and the real economy will become increasingly evident in a higher interest rate environment. My assessment has long been that that high debt levels will constrain the ability of central banks to raise rates. The challenge is that core inflation remains elevated in the US, the EU, and elsewhere, as this week’s data has shown again.

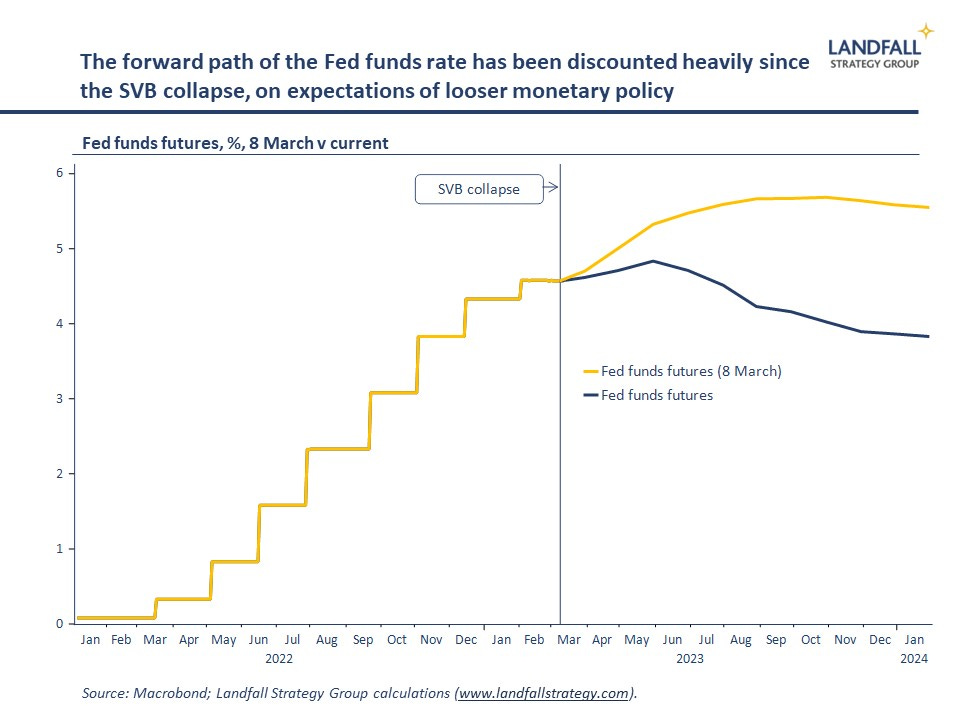

Markets have re-rated the expectation of further Fed rate increases: the previously expected 50bp increase next week is now expected to be 25bp (or lower). The expected path of the Federal funds rate is much lower (>150bp lower by January 2024) than immediately before the SVB collapse, the terminal (peak) policy rate has been repriced by ~80bp, and the 2 year US government bond is down by >100bp.

Similar movements have been seen in European markets, where sovereign debt levels in several countries remain very high. The ECB’s decision to raise the policy rate by 50bp yesterday (as had been expected prior to SVB) shows that reducing inflation is the primary focus in the eurozone - at least for now. Indeed, core inflation in the eurozone is higher than in the US.

Even so, there are early signs of ‘financial dominance’, where central bank decision-making is shaped by debt loads and financial stability. Note that the ECB removed language on the future path of rates from yesterday’s statement. The SVB experience will shape the path of interest rates (lower) and inflation (higher) in the US and around the world. Silicon Valley continues to change the world.

Chinese decoupling

The US is moving to reduce its economic exposures to China, and to decouple its economy, particularly in the technology space. Decoupling is more evident in terms of investment flows than trade flows so far: US/China trade flows remain at record levels. And the EU is looking to diversify its exposures, with recent statements aimed at building greater resilience in supply chains for critical imports.

But decoupling is not simply a Western policy. China has been looking to reduce its economic exposures to Western economies for some time: the Made in China 2025 plan as well as various Belt & Road Initiative measures. The Western sanctions in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have accelerated this process of decoupling by China.

Although still early days, China’s changing import profile provides a sense of changing positioning. There is a reduced share of imports from the US, Japan, and South Korea since 2015, and an increased importance of ASEAN. Some of this reflects supply chains adapting to changing patterns of economic development.

But there are some political drivers as China looks to source imports from jurisdictions that are friendlier. Imports from Africa and Latin America have been moving up. And there have increases in the import shares from Russia and the GCC, notably over the past year: this partly reflects energy price increases, but also a rotation of footprint.

Europe’s import share has been increasing, but this will come under downward pressure as restrictions on technology exports to China become more widespread (note ASML). And commodity-heavy exports from Australia and New Zealand have also increased. But overall, imports from ‘the West’ continue to decline.

This is over and above China’s inward turn. China is looking to be more self-sufficient in a range of strategic areas, with its imports share of GDP reducing.

Brexit & Northern Ireland

The additional trade frictions as a result of Brexit have led to a meaningful drag on UK exports to the EU, as European countries source goods from elsewhere. However, the UK’s imports from the EU continue to grow rapidly, with a growing trade deficit between the UK and the EU.

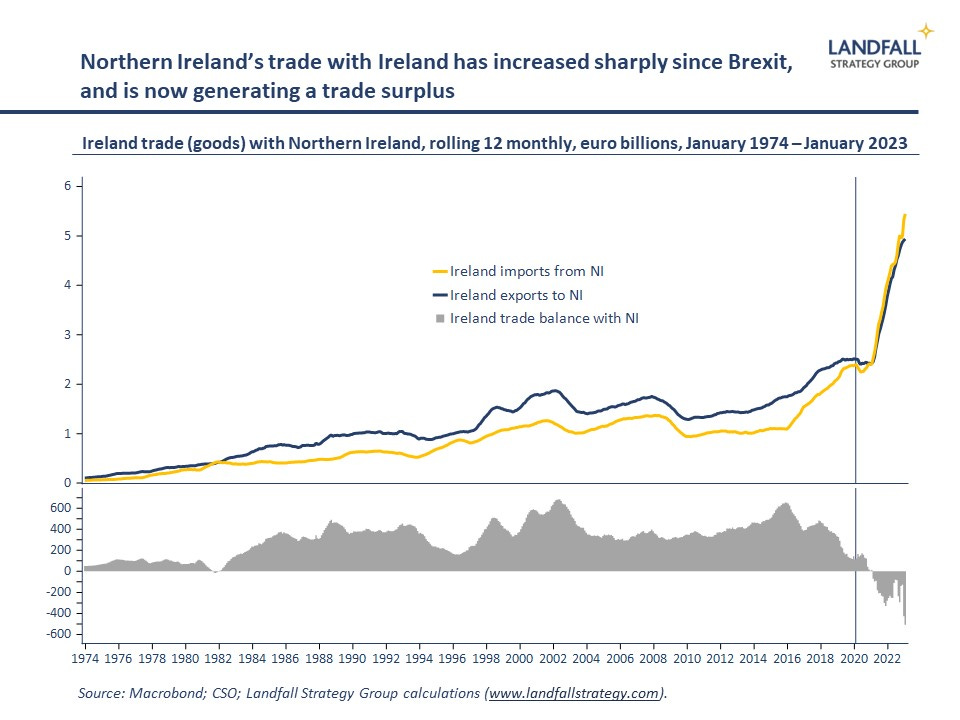

However, one part of the UK for which this drag is demonstrably not true is Northern Ireland. Since Brexit, there has been a substantial increase in trade between Northern Ireland and Ireland: merchandise exports from Northern Ireland have increased by >2x since Brexit in 2020, from ~€2.4 billion to ~€5.5 billion in the 12 months to January 2023. And Northern Ireland’s long-standing trade deficit in favour of Ireland has reversed.

This performance is largely because Northern Ireland has retained dual access to the UK market as well as to the EU via Ireland. The recently agreed Windsor Framework confirms Northern Ireland’s distinctive status in the UK. As PM Sunak said recently in Belfast, ‘Northern Ireland is in the unbelievably special position of having privileged access, not just to the U.K. home market … but also the European Union single market…. That's like the world's most exciting economic zone!’.

This of course rather begs the question as to why Brexit is a good idea for the rest of the UK. Indeed, Northern Ireland’s experience relative to the rest of the UK provides a measure of the economic impact of Brexit.

Although Northern Ireland has been one of the thorniest issues in the Brexit negotiations for a range of technical and political/constitutional issues (and the DUP this week objected to the terms of the Windsor Framework), Northern Ireland stands to reap a range of economic benefits in terms of export opportunities as well as attracting FDI.

Farewell to global supply chain disruptions?

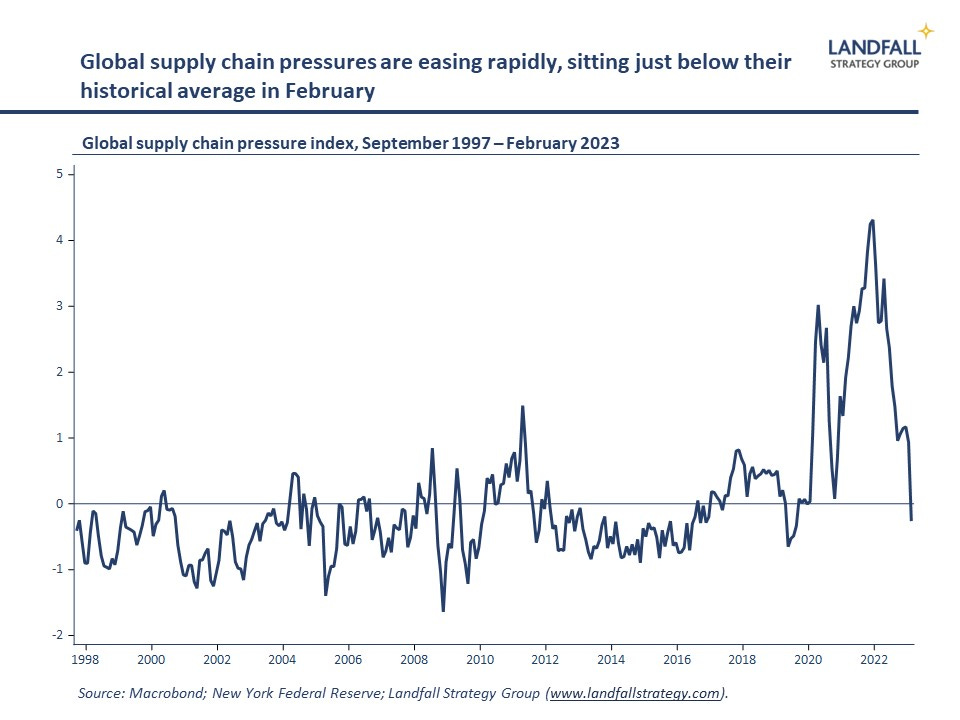

The global supply chain disruptions as a consequence of the pandemic continue to ease. A composite measure of global supply chain pressure produced by the New York Federal Reserve (that includes measures of air and shipping costs and delays) is now sitting just below its historical average. The supply chain pressure measure has reduced sharply from as high as 4 standard deviations above average in in December 2021.

Container shipping prices have reduced as blockages are removed and as world trade continues to contract. This will lead to reduced production costs and delays, supporting the disinflationary process. However, China’s rapid reopening process may create some additional stresses.

But supply chain risks have not disappeared, even as some of the pandemic disruptions ease. We are moving into an environment in which supply chain risks will remain structurally elevated. Firms and policy-makers need to adapt to these realities, building greater resilience into supply chains. [For a discussion of these issues, refer a paper on global supply chain dynamics that I prepared for the New Zealand Productivity Commission].

As one reminder of the challenges, the Rhine has been at close to record-low levels because of a dry winter – this river is a major artery for industrial goods between Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands. Low river levels last summer caused major economic costs and disruptions as firms were unable to transport goods efficiently; road and rail options were much more expensive. These type of climate-related disruptions to global supply chains are likely to become more frequent.

And aggressive industrial policy in large countries and growing geopolitical tensions are likely to lead to the fragmentation of global supply chains, which will likely increase costs. This is seen already in semiconductors and green technologies, and is likely to spread: note the Inflation Reduction Act in the US and the pending Net Zero Industry Act and Critical Raw Materials Act in the EU.

Israel

A diplomatic breakthrough between Iran and Saudi Arabia, brokered by China, was announced in Beijing last week. Diplomatic relations will be restored along with other measures, reducing the risks of conflict, although relations remain frosty.

This reflects the ongoing rebalancing in the region. The Gulf states are carving out a more independent positioning, including on Russia/Ukraine, and are reducing their reliance on the US. China is developing a stronger diplomatic and economic role, partly reflecting China’s interests in energy imports from the region. And it highlights the diminished role of the US: the US remains a significant economic and security player, but it is looking to reduce its investment in the Middle East in response to changing strategic priorities (notably in Asia).

It also further complicates the strategic environment for Israel. Israel’s economic and political relations with countries in the region have been improving rapidly after the Abraham Accords, and the establishment of relations with Saudi Arabia was being discussed. But the deal with Iran removes a key element of potential alignment.

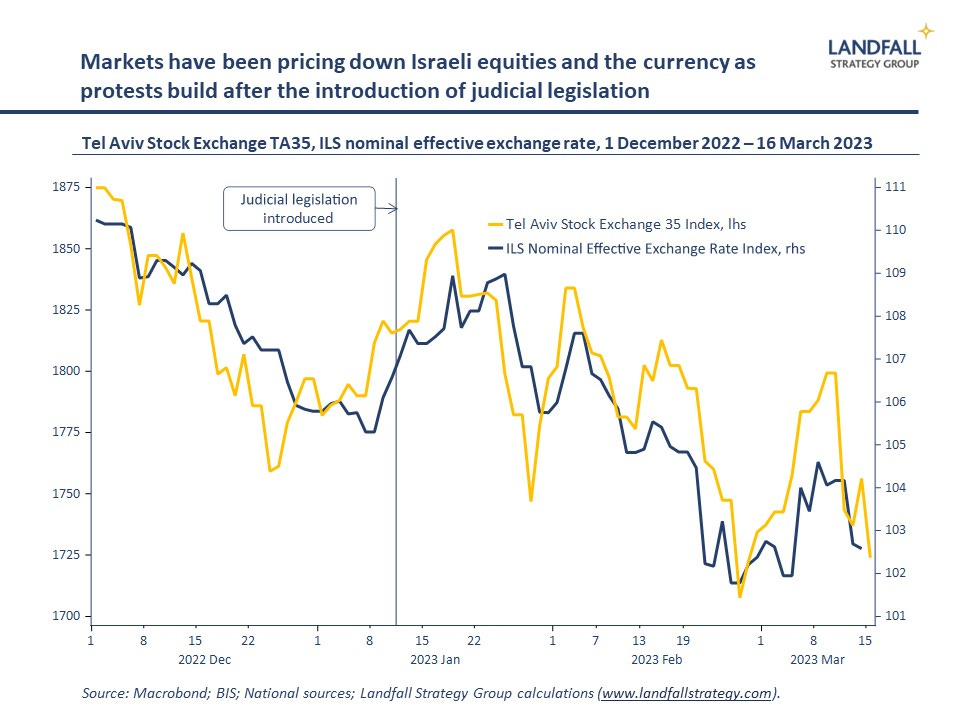

Israel also faces severe domestic challenges. Israel has long been distinctive in the region in rankings of institutional quality, democracy, and so on. But the new coalition government is eroding judicial independence and other institutions. This has provoked mass street protests since January with hundreds of thousands of people in the streets, threats from Israel’s important tech sector to exit or downsize, as well as boycotts from military reservists. Markets are pricing down Israeli equities and the exchange rate.

A key small economy lesson is that the margin for policy error is very low (think Greece, Iceland). Israel needs to effectively manage both its domestic political situation and the changing strategic context in the region in order to sustain performance. I wouldn’t bet against Israel, but things can unwind quickly in small economies.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

5 Comments

Keep watching XAU

Interesting how authoritarianism, brutality and protests is cutsie labeled "wobbles" for Israel. Many other countries would be labelled aggressively as dictatorial, anti-democratic and unstable.

To illustrate what happens when supply chain goes wrong. A story from the weekend. Funko toys. The maker of Bobble Heads is in the process of destroying between $30 million and $36 million worth of inventory after surplus stocks strained its fulfillment network and ratcheted up operating costs. They said that storage costs for holding the inventory excess knocked more than five and a half percentage points off gross margin. Since the pandemic, they added $85 million in annual fulfillment expenses despite very similar overall throughput in the distribution center. The sheer amount of stock essentially got in the way as teams worked to fulfill orders.

...in New Zealand by 400bp.

Yet we're still running budget deficits. I would welcome the return to more prudent targets on debt levels now the pandemic is effectively over.

David, re CS, the wipe out of hybrid bond holders...... makes one wonder why you would hold these now.

For sure for other banks, their pricing now is the litmus test of that banks problems.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.