By David Hall, Melody Meng & Nina Ives*

Until now, the government’s approach to climate action has largely been about getting the policy architecture right. This work is vital, but it’s more about rearranging possible futures, less about emissions reductions in the near term.

The newly released Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) was supposed to shift gears, to get real about urgent climate action – and it partially achieves this, but only partially.

Budget 2022 will reveal some extra expenditure, but most of the $2.9 billion of climate-relevant funding was confirmed alongside the ERP. It exhibits a sensitivity to the electoral constraints on transformation, less so a sense of realism about what decarbonisation actually demands.

There are significant steps forward. Resourcing for Māori involvement in climate policy is long overdue. Integration of education and social support measures is also helpful.

In this sense, the ERP process is itself a minor victory. For years, policy scholars and public sector mandarins have championed the ideal of joined-up government, without ever doing much in practice. Consequently, the ERP is unique, even unprecedented, by taking a whole-of-government approach, weaving together all core government departments in a 340-page report.

Time to be decisive

Some of the best bits of the ERP play to this interconnectedness. Nature-based solutions – that is, enhancing natural ecosystems to address multiple challenges – emerge as a strong connective theme, not only between various sectors, but also across the National Adaptation Plan and Biodiversity Strategy/Te Mana o te Taiao.

The same can be said for planning and infrastructure which is explicit about the overlapping opportunities to reduce emissions across multiple sectors.

Similarly, the rising theme of the “bioeconomy” sheds new light on the importance of forestry, not only as a supplier of timber and carbon removals, but also as feedstock for bioplastics and biofuels to substitute crude oil.

But instead of investments to make this happen, the ERP promises a bioeconomy and circular economy strategy that won’t be complete until 2025. This is the overriding character of the document, where a large proportion of “actions” begin with the words “explore” or “investigate”, or lapse into research, baseline setting and elongated work programmes.

Even well-established ideas, such as congestion charging, are deferred. The government has investigated this policy for more than a decade, but the ERP only confirms it is “considering progressing legislative changes to enable congestion charging”.

The ERP was the moment to be decisive, one way or the other. The failure to do so leaves a lingering suspicion that the ERP’s new slew of pledges may face a similar fate.

Acceptability over ambition

So there are plans, and plans for plans, but still a shortfall of strategy. Energy sector policy, for example, takes a technology-neutral approach rather than narrowing down on priorities, such as geothermal energy, where Aotearoa is known to have natural advantages, expertise, and potential for global impact.

Such opportunities are already identifiable, even in the absence of a central energy strategy (due in 2024). Research, development and deployment take time, so strategic decisions need to be made now, rather than backloaded for later this decade.

The proposal of “climate innovation platforms” might provide the vehicle for strategic innovation, but only if properly resourced. The ERP gives an air of compromise, tending toward acceptability over ambition.

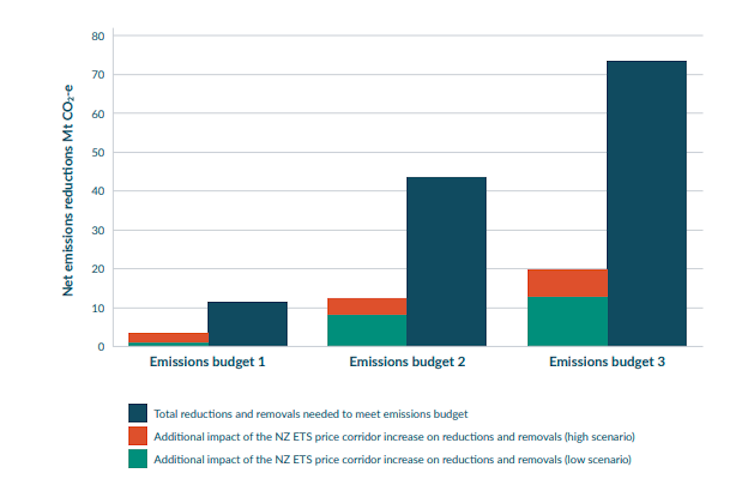

Fortunately, though, the proposed policy mix – along with an improved Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – will take us quite some way.

Emissions pricing in the ERP

The NZ$69 million Government Investment in Decarbonising Industry (GIDI) fund is being topped up with nearly $680 million, a ten-fold increase, to accelerate industrial decarbonisation.

In transport, this includes $350 million for cycleways and public transport, $40 million to decarbonise the bus fleet by 2035, $20 million to decarbonise freight transport, and $20 million for a vehicle social leasing scheme trial.

Agriculture is also the beneficiary of $710 million from ETS auctioning revenue for agri-tech and research – arguably unfairly, given that agriculture currently sits outside the ETS.

Dependence on cars

Overshadowing these initiatives is the scrap-and-replace scheme, aimed at subsidising people into electric vehicles (EVs), and already a lightning rod for controversy. The empirical record for scrappage schemes elsewhere, such as the US Cash for Clunkers programme, tends to conclude that emissions reductions are minimal despite the high investment.

Given that replacement cars must be EVs and hybrids, the New Zealand scheme may produce more emissions reductions than previous schemes did. However, the high price of EVs may mean that, even with high subsidies, low-income households cannot easily cover the difference.

Also, the scheme risks perpetuating the dependence on cars that makes transport mode-shift so elusive. Indeed, the $569 million committed to scrap-and-replace is far larger than the $350 million committed to cycleways and public transport.

It is hard to resist the conclusion that a scrappage scheme – for all the flak it will receive from efficiency-minded economists – was perceived as more politically palatable than getting people out of cars.

The political challenge

The ERP is projected to drive enough change to meet New Zealand’s 2030 Paris Agreement pledge. But part of this effort will involve the purchasing of emission reduction credits on international carbon markets, at potentially high prices.

A high reliance on paying for other countries to reduce their emissions reflects a hangover in the New Zealand government’s thinking, dating back to the Kyoto Protocol era. Deferring hard choices now by “planning more plans” might reduce the risk of backing the wrong technologies, but deferral is not without its risks either.

It speaks to the longstanding problem of treating climate change as merely a scientific, technical problem. This implies that, like any puzzle, climate action will benefit from further discovery, analysis and evaluation.

For elected and unelected officials alike, this is irresistible, because commissioning further research and strategy is a way of appearing serious, even prudent, while also avoiding vital decisions and associated responsibilities. The slow-moving quality of the climate crisis, in contrast to the fast-moving pandemic, increases the window for dawdling.

But climate action was always fundamentally about politics. The ERP practices the arts of acceptability but neglects the art of the possible – of making ambitious commitments and bringing the people along.![]()

*David Hall is a Senior Lecturer in Social Sciences and Public Policy at the Auckland University of Technology; Melody Meng is a Research Fellow at the Auckland University of Technology, and Nina Ives is a Climate Change PhD student at the Auckland University of Technology This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

32 Comments

A missed opportunity to be decisive

"Decisive" LOL, this is Labour, their policies are "ideas", but they are not "decisive", "detailed" or ever "implemented"

Labour weren't " shovel ready " in 2017 when Winston Peters shocked them by installing them as government ...

... 5 years later ... the shovels got rusty out in the rain ... we're still not ready ... Labour are still " investigating a possible framework " ... still consulting ... still full of waffle waffle ...

Let's leave it to private enterprise then shall we? (who have done sweet F.A. in 40+ years except milk the infrastructure that was built over the previous 40 years)

Judging from how Kiwibuild (and many other so called flagship projects, remember W Peter's the Regional Econ Development project? spend $100mn each year for three years. Where did that thing go??? no questions?) ended and how long (10 years) it took to put a 27km TMG in place, the ERP will be either a total failure or taking 100 years to see some progress.

TMG would never have been completed , had the Gnats not got it started ... Labour / Greens are anti cars , anti roads ...

... on ya bike , pal ... a slow train .... bus ???

You are tiresome - find three rellies and some old rims?

Nobody is 'anti-car' - that is disingenuous spin (indeed, it is a long time since this poster put up a serious comment - an interesting phase-change, it was....

What they are, is anti resource draw-down, anti-pollution, and anti biodiversity loss. It the buck stops at certain points, that is a consequence.

... I'm wondering how much extra coal we'll have to import from Indonesia , and burn at Huntly , to create the extra electricity to power up Kiwis spanky newly subsidized EV's ...

Depends how much the pro growthy yeasts get their way, in an energy constrained world, I guess?

It missed the opportunity because it doesn't know the meaning of the word.

"It is hard to resist the conclusion that a scrappage scheme – for all the flak it will receive from efficiency-minded economists – was perceived as more politically palatable than getting people out of cars." - sounds about right

I'm in the mindset that a true emissions reduction plan would include better ways to lower the dependence of the personal car while still maintaining freedom.

It seems that we're instead focusing on removing the dependence on fossil fuels, which I can entertain, however I was under the (potentially misinformed) impression that the best approach to lower emissions and reduce waste when it comes to vehicles is to live out the life of your existing vehicle, reduce time on the road and unnecessary trips, then upgrade to electric when necessary. Batteries aren't clean and green either, and there is a limit to the amount of electricity that can be drawn from the current grid, are we really ready for this?

As the article states, without strategy it's difficult to see how this all fits together. Energy source is first, then logistics, then infrastructure. A nation driving electric vehicles is an outcome not a solution - given lithium is finite, trains trains trains.

Jumping the gun on electric vehicles there is several other options in the wings and we may find that we have backed the wrong horse . It would be better to get on with the things that are achievable now .sorting out electricity supply and distribution would be one . Encouraging more use of public transport another . Chasing political rainbows won't help in the long run .

... you're 100 % onto it ... EV's are the worst possible choice , hybrids are the best current option ... and , in the future , hydrogen ...

But ... the current government are ideologically driven ... anti ICE , anti roads ...

I strongly disagree. The technological improvements over the past few years has been impressive. Better performance and far cheaper to run than an ICE. Recharge 300 km in the time it takes to drink a cup of coffee. No Greenhouse gas or particulate emissions. Energy recovery through regen braking. Batteries last the lifetime of the car because of better temperature management. The disadvantage is that you are looking at over $65K for a new vehicle.

Electric hot water will cost approx $1200 a year to run. Solar hot water installed at scale would be about $5000 per household from Auckland north. Scrappage low emission vehicle scheme spend $569 million could convert 113800 low income households to solar for free. Those households would save $100 a month on hot water costs for the next 20 years. The electricity to heat the hot water now comes from burning coal at Huntly. So that coal burn could be lowered as well. Who knows we may even be able to make the majority of the solar water heating components locally and get some extra jobs out of it as well.

Currently use gas bottles for all hot water and cooking cost $1000approx to install monthly $35.00 approx two people in the house .

Seems a bit on the low side to me. Gas is nearly double the price per kWh. Using 30c/kWh for electricity, gas is around 49c/kWh, maybe as low as 45c/kWh Must be short showers and and every other day per person.

Use 9kg bottlesvfrom bunnings approx $35.00 lasts approx 4 weeks an d we shower daily often twice depending on needs . Gas stove and oven quite a few meals are baked so stove used every day .

How dare you make sensible, practicable and easy to implement suggestions! Where is the ideology, grandstanding and virtue signalling? Before you can have a sensible decision you need a vision, obfuscating strategy followed by several working groups so you can ignore their advice. Then we need announcements about announcements about a plan for a plan. And only after you have wasted about $100m then can you make such a suggestion.

... brilliant ! ... bloody brilliant ... most useful post I've read around here for a damn long time ...

This is waaay too practical and besides, we'd need a committee to look at this first, write a report, review said report and then reject it.

Our house uses solar PV to heat our hot water. Yesterday it was cloudy all day and we saved (according to our system) 0.1kWh through solar. The day before we saved 2.4kWh. The day before that we saved 9.4 kWh. On the days it works, it really works. The days it doesn't, it's bad. While solar PV is different from solar hot water, the principle remains - be prepared for 1m, warm showers on the days you most need a hot shower.

According to these guys a solar hot water system would provide 40-60% of your hot water needs in winter. From my experience, it's about that for solar PV hot water too.

Not an expert but solar water heating in a UK winter where those guys are based would be a tough sell. Auckland and Northland however would be considerably warmer and sunnier in winter than the UK. The systems still have a hot water cylinder involved. But the water going into the cylinder is preheated by the sun. Usually to a higher temp than what the cylinder is set for. So the new hot water introduced helps to maintain the temp of the stored water in the cylinder. The electrical element does not need to fire up as much to heat the water.

Used to do solar hot water. Had a few customers that never turned their element on. A year round average of 60 to 80 % could be expected from a decent system. We would oversize the clylinder so they would have a few days storage . legionaires disease mean't the cylinder had to go hotter than 55 degrees, and they started to require controllers to ensure that , plus all sorts of safety valves , which blew the costs out of the water. plus installer courses every year . Pv hot water is now cheaper. a solar / wetback combo is ideal .

Yes we have that combo. We have people at home during the day so those days there's no sun in the winter we at least have the wetback, which is worth about a kW. Some days it boils the cylinder. The days there is sun there's no fire required.

Shaw gave a secondhand Prius as an example of the car they could help people in. 1237 on trade me right now , and availiable by the boat load from Japan.

... secondhand ... so , the batteries are well used ... what's the cost of a replacement set , $ 5000 ... $ 10000 ... did James Shaw mention that ...

Ask any taxidriver why they use them .

... around here , only seen taxi drivers in ICE ( lots ) , hybrids ( some ) ... EV's ? ... zero ...

ya see what you wanna see.

.. nah ... only see wots there ... Toyota priuses are common taxis ... no EV's ...

Comprehensively incomprehensive...not even close to enough. Greens need to oppose it and if James Shaw loses his Ministerial post then so be it. Plenty of time for this once the dust settles. National/ Act policies are beneath contempt.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.