By David Skilling*

The horrifying pictures out of Ukraine this week of war crimes committed by Russian forces have intensified calls for tougher economic sanctions to be imposed, from oil and gas bans to a complete removal of Russian banks from SWIFT. Moral outrage is intersecting with economic decision-making.

Previous notes have argued that the Russian invasion and the accompanying sanctions will accelerate global economic fragmentation. The behaviours of Western-aligned governments and firms over the past several weeks show that there is a strong political values motivation to these dynamics, as ties with Russia are cut in response to breaches of international law.

Sanctions as symbols

Relative to initial expectations, the economic sanctions imposed on Russia have been strong and broad-ranging – although ongoing exports of oil and gas to Europe remain a large hole.

There are a few motivations for imposing sanctions on Russia: to drive Mr Putin to the negotiating table by imposing economic costs; to impose punishment and to signal condemnation of Russia’s actions; and to credibly show to future aggressors that economic sanctions will be imposed if international law or other norms are breached.

The economic sanctions are unlikely to meaningfully change Mr Putin’s decision-making (particularly when they exclude oil and gas exports). Perhaps over the next months, sanctions will constrain options and stop Russia’s war machine from working. But changing the near-term balance on the battlefield requires military support more than economic sanctions.

Indeed, economic sanctions have a very mixed history in delivering results (see this piece by Nicholas Mulder, author of a very good recent book on economic sanctions).

Instead, the core motivation for economic sanctions seems to be a combination of punishment of Russia for its barbarism and breaches of international law, as well as to strengthen the credibility of threats to use economic sanctions in the future.

The message is that Russia’s brazen breach of the rules-based system will result in its ejection from the global economic and financial system, even if it does not immediately shape Russia’s near-term behaviour. Indeed, it is not clear what conditions need to be met for these sanctions to be lifted; it is very unlikely that sanctions will be relaxed without fundamental political change in Russia.

So although they impose substantial economic costs on Russia, the sanctions are symbolic as much as instrumental in nature.

And of course, national interests still matter. Many European countries remain frustratingly wary of the higher energy costs that would come from further sanctions. But countries have been more willing to impose and absorb economic costs than was expected prior to the invasion.

From economic engagement to competition

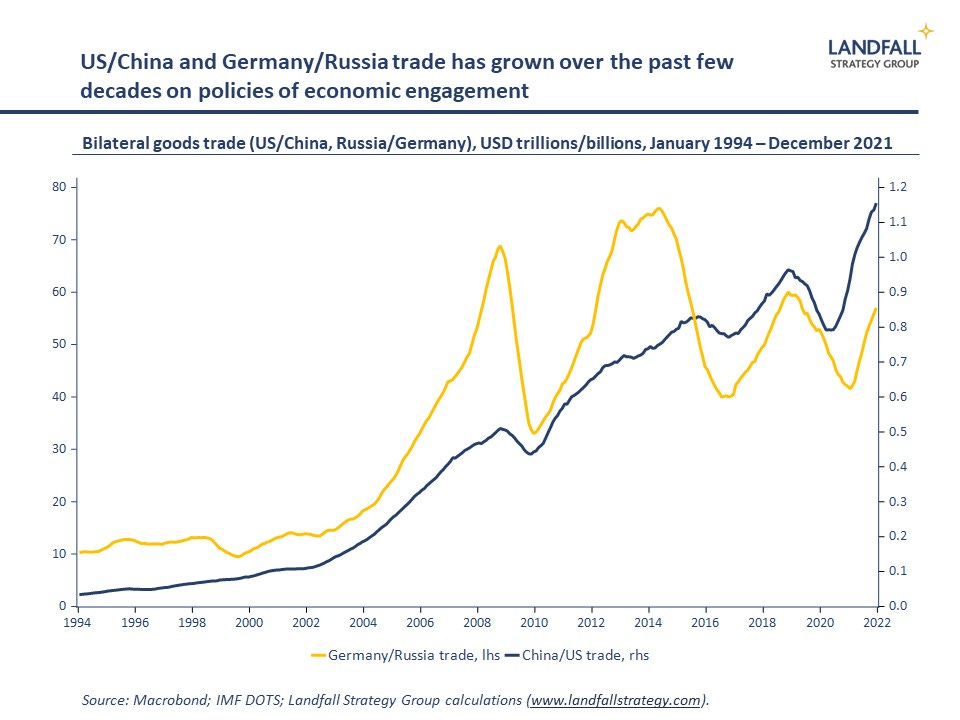

The Western-led sanctions on Russia also reflects a reversal of the belief that economic engagement will lead to convergence in political systems and behaviours. Germany has discovered the limits to the benefits of economic engagement with Russia (epitomised by Nord Stream 2), as has the US with respect to its China engagement policy over the past few decades.

Neither engagement approach led to meaningful rapprochement. Instead, there are now elevated levels of conflict and strategic rivalry. Indeed, some political voices argue that this engagement approach strengthened strategic competitors. Germany has admitted it was naïve, and the German President recently apologised for ignoring the warnings of countries who criticised Germany’s Russia policy. In Washington, a hawkish economic stance on China is one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement.

There is a shift underway to a more hard-headed approach. Whereas Western governments previously tried to use economic engagement to shape political values in its economic partners, differences in political values are now shaping economic flows as Western countries increasingly engage with countries that conform to the rules-based system.

The experience of the past several weeks suggests that minimum adherence to the rules-based system (notably respecting territorial integrity) is now needed in order to fully participate in the Western-led global economic and financial system.

This greater focus on rules and values does not imply Western values universalism where every trading partner needs to be a liberal democracy. Indeed, there are plenty of flawed democracies in the West; and the West does not have clean hands after Iraq, Afghanistan, and its tepid response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine. But a brutal invasion by a UNSC/G20 member is treated as a red line.

In any case, Western views on human rights are far from universally held. Yesterday’s UNGA vote to remove Russia from the Human Rights Council was passed, but with 24 votes against and 58 abstentions (including Singapore, which has sanctioned Russia for breaching international law).

Stakeholder pressure

The increasing importance of values can also be seen in corporate behaviour. Over 600 largely Western multinationals have now withdrawn from Russia. If anything, companies have been more forceful than governments in imposing costs on Russia.

There are several reasons for exiting the Russian market: the impact of official sanctions; supply chain disruptions that constrained Russian operations; stakeholder pressure; and, for some, taking a principled stance.

For many firms, stakeholder pressure has been the dominant contributor to the decision to exit. The barbaric Russian invasion – reinforced by Ukrainian success in the information wars – has created an environment in which firms have been under huge pressure from staff, customers, and public opinion to exit Russia. Firms, such as Nestle, that tried to justify an ongoing presence have been punished.

‘We found ourselves thrust into global politics like no other moment in recent history’, Mark Schneider, Nestle CEO

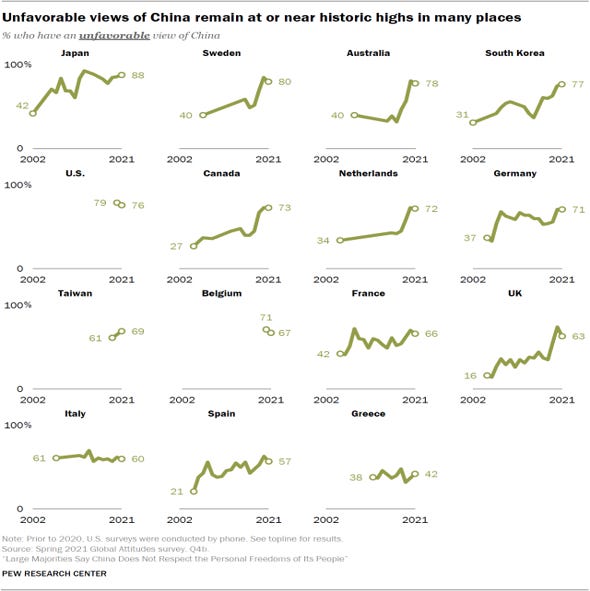

For many firms, exiting Russia was a painful but relatively straightforward choice to make – it accounted for a small proportion of earnings. But to the extent that geopolitical relations worsen between China and the West, and stakeholder concerns about issues such as human rights and Taiwan rise, stakeholder pressure may make a China presence more problematic for Western firms.

At a company level, the extent of decoupling from China is partly driven by economic logic – reducing exposures to geopolitical risk and building supply chain resilience, offset by the large market and competitive advantages available in China. But values-based stakeholder pressure adds another dimension to this decision-making.

Indeed, some firms are already struggling to satisfy stakeholders in both China and their home market. These pressures will likely strengthen.

Looking forward

The experience of the past several weeks shows that economic and commercial relations are not a values-free domain. Breaches of international law have been met with aggressive responses from governments and firms. These behaviours will shape the future of globalisation.

Some of the economic decoupling underway is due to strategic competition between big powers as they grapple for dominance in areas from technology to finance. This will be reinforced by values-based behaviours by governments and firms, as countries that breach international law and norms are sanctioned. The blocs that form in the global economic system are likely to be organised around shared values as well as common strategic interests.

There will be practical limits to this values-driven decoupling. It is much less costly to aggressively sanction Russia than it is China, a large and central part of the global system. But expect differences of political values to become an important driver of global flows, as governments and firms respond to citizen and stakeholder pressure.

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

10 Comments

In any case, Western views on human rights are far from universally held. Yesterday’s UNGA vote to remove Russia from the Human Rights Council was passed, but with 24 votes against and 58 abstentions (including Singapore, which has sanctioned Russia for breaching international law).

Hanoi's skepticism of UN runs deep. Former Foreign Minister Nguyen Co Thach once answered the press: ‘We don't have such a high regard for the UN as you do.' ‘How so?’ ‘Because during the last 40 years we have been invaded by 4 of the 5 permanent members of the Security Council.’ Link

As deplorable as Russia's invasion of Ukraine is, nobody who has been paying any attention to world events over the past two decades can possibly believe that we have a "rules-based" global order, or that the sanctions being imposed on Russia have anything to do with humanitarian Western values.

Bombing hospitals, rape, deliberate killing civilians - those are against all humanitarian values. They would be understood by a newly discovered tribe in the mountains of PNG.

Specifically Western values might include democracy, women's rights, acceptance of homosexuals, legal abortion, torture being illegal, universal education. And where were those values in the west 250 years ago?

From a European perspective, the sanctions are idiotic. Like cutting yourself to punish a bully.

Post WWI, the isolated trading position of Germany and the Soviets just led to them developing their own full spectrum domestic industries. Further, the lack of connectedness with the rest of the world made military conflict more, not less likely.

In ten years Russia might actually be better off than the West. They will certainly have the lowest energy input costs of any industrialized economy and reliable access to food.

The EU has learned that assisting the economic development of poor neighbouring countries is cheaper and more effective than military expenditure.

"In ten years Russia might actually be better off than the West." Depends by what measure? Sure, Western capitalism is all about burning through your resources as quickly as possible, to maximise return on investment, and this will leave the west a depleted husk when infinite substitution is found to be a crock of ...., but better to be free and poor, than living in a totalitarian state run by a self entitled nutcase and still poor.

Russia has had low energy input costs and the lands available for reliable access to food for much of it's history. The majority of it's people have been self reliant but impoverished for much of it's history.

Russia has not transitioned to a point where the majority of it's citizens can access a comfortable standard of living. On it's current trajectory in ten years time Russia will not be better off than the West regardless of how much gas and minerals Russia has. Russia will still have a small wealthy elite, a tiny middle class and a large population that live hand to mouth.

The purchasing power provided by a large middle class will not be available to Russia because a large middle class cannot exist within a kleptocracy.

When the thieves at the top of a society take all the resources of that society because there are not the institutions with the strength to stop the plunder then the middle class is reduced. This is a lesson not just for Russia or China but for the US, Europe and New Zealand.

Ukraine is fighting for the chance to be a different society to Russia. The chance for individuals and families to put money aside and build businesses, dwellings and lives that reflect their own self image. The chance to build a society where individuals get a chance for self expression that is not stolen or censored by a narrow elite at the top of the society.

I support that fight for every individual to be able to express and develop their own talents, and I support the Ukrainians in their bid for these freedoms.

I would not claim to have any insights into how the invasion of Ukraine will eventually play out, but it seems reasonable to guess that Europe will never want to return to the previous energy policy with its undue reliance on Russia.

It also seems reasonable to assume that Europe will pay more to beef up the military capability of NATO.

Finally, it's hard to disagree that the 'old' globalisation has gone and will be replaced by a more limited version.

When Mr Putin gave the command to start a war, did the stake holders know about it.

When the killing starts, all ties are broken. No trade, only warfare. Neighbours decide to be friend or foe. Or be neutral. Sanctions are auto - no need for a declaration.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.