This article is a re-post from Fathom Consulting's Thank Fathom its Friday: "A sideways look at economics". It is here with permission

By Kevin Loane*

In an increasing number of marketplaces, such as Airbnb and Uber, customers rate their service provider, and get rated in return.

Potential downsides from this evolution were explored in a Black Mirror episode that described a future where personal ratings determined everything from which neighbourhood you lived in to the type of car you could rent. But this trend needn’t be scary.

In theory, it should lead to efficiencies.

Many transactions take place with asymmetries of information. Does this hotel have bed bugs? Is my taxi driver trustworthy? Is that food truck following even the most basic of health and safety standards? Previously in these circumstances, you may have had to trust your gut. In the latter example, perhaps to its own detriment. Public ratings post-transaction should increase the information available to future buyers, improving spending decisions as a result.

In reality though, how much additional value do these ratings provide?

Either your Uber driver successfully navigates a Prius from A to B without incident, so you give them five stars, or they get animated listening to LBC and almost cause an accident, and you still give them five stars — in my case at least. It’s possible that my consistently positive ratings are unique. An unnamed Fathom colleague unashamedly admits to knocking a couple of stars off for ‘loud and lousy music’. Evidence suggests this could be borderline sociopathic behaviour.

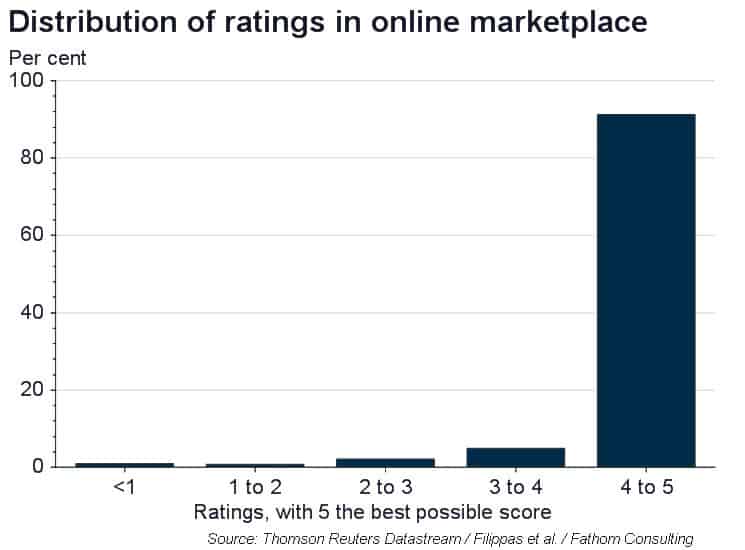

Work by Apostolos Filippas et al.[1] finds that 91% of ratings delivered on an anonymous online marketplace were 4 out of 5 or above. Within that, 82% were 4.75 or higher. Moreover, ratings tended to become increasingly skewed towards the top the longer that service was in existence. A trend of so-called reputation inflation has been detected across many platforms.

There are two broad theories that explain it. It’s possible that Uber drivers and the like are getting better over time, and customers’ ratings simply reflect higher satisfaction as a result. Increased competition could be one possible explanation for this. However, it seems more likely that customers feel increasingly guilty about leaving negative reviews, because there’s an emotional cost to them in doing so. This could be due to fear of retaliation, or, more probably, concern that the employment prospects of the reviewee will be negatively affected. Such guilt will be higher when customers interact personally with the service provider in question, as is the case with taxis. It turns out that ratings inflation may have risen as customers become more aware of the consequences of poor ratings. It also turns out that most humans are quite nice on the whole.

So that’s the problem, but what’s to be done about it?

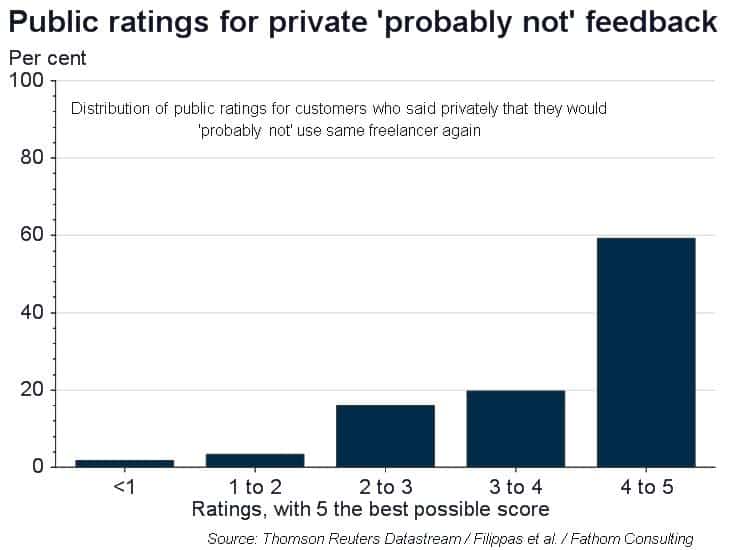

Allowing customers to leave private reviews has been found to encourage honesty and leads to a more even distribution. But secret ratings would undo the main benefit of public ratings: increased information-sharing. In any case, concurrent public-private ratings systems only show a small improvement. For example, almost 60% of customers who privately said that they would ‘probably not’ use the same freelancer again left them a public rating that was four stars or more. Platforms could enforce a distribution for ratings, as is done with tests such as the SAT. However, this would probably be seen as unfair on those being reviewed, and customers would probably not go for it either.

With the rise of the sharing and gig economies, where customers increasingly interact more closely with individuals rather than companies, reputation inflation is probably here to stay.

We may just have to accept it.

Perhaps this is a situation where we shouldn’t let perfect get in the way of good.

In sectors where public review systems have been introduced, there seems to be a clear increase in the quality level of the service provided, if not its rate of growth. Fellow South Londoners who no longer struggle to find a cab home after ten would probably agree. That alone is worthy of a six-star rating.

[1] Apostolos Filippas, John J. Horton, and Joseph Golden, ‘Reputation Inflation’ (2018). Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3136473.

Kevin Loane is an economist at Fathom Consulting in London, England. This article is a re-post from Fathom Consulting's Thank Fathom its Friday: "A sideways look at economics". It is here with permission

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.