By Patrick Watson*

The Federal Reserve hiked interest rates again last week. Yes, it was a tiny hike, but as they say, “A quarter-point here and a quarter-point there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”

Higher rates aren’t entirely bad. They might help savers holding cash - though I wonder why anyone would still hold cash after almost a decade of punishment. The Fed has forced Americans into riskier assets, using every tool but horsewhips.

The bigger question is what this tells us about future Fed policy. Given that the Fed’s composition will probably change in the next year, what if we let the math decide?

Fed Formulas

This summer I’m taking an algebra class at Austin Community College. Math’s right-or-wrong nature presents a nice change from the ambiguity of macroeconomics and monetary policy.

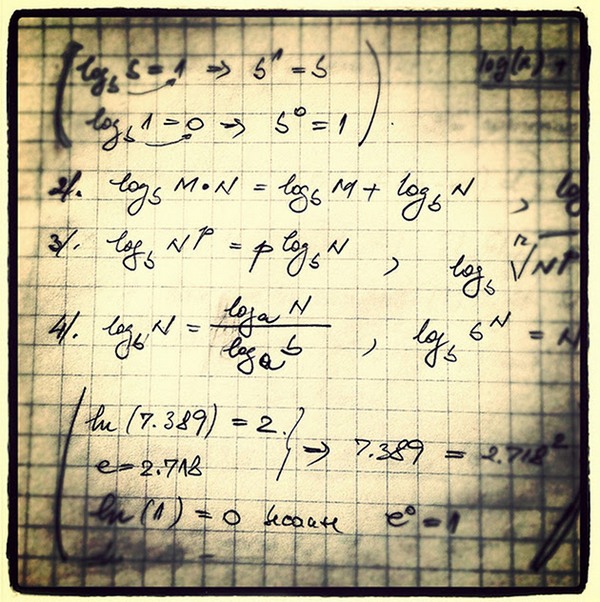

One evening last week, I sat on my deck, happily solving equations from my algebra book - not thinking about economics at all - when I saw this.

Since there’s evidently no escape for the Fed-weary, let’s discuss this formula.

Harvard economist Greg Mankiw designed it to assess what interest rate the Fed should target, based on inflation and unemployment.

At the time (mid-2006), the unemployment rate hovered around 4.6% and core inflation 2.4%. Plug those numbers into Mankiw’s formula, and you get a 5.42% rate target. The actual fed funds rate was 5.25%, so not far off.

However, that picture has changed quite dramatically.

The Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, core PCE, is up 1.7% since this time last year, and the unemployment rate is 4.3%. So according to Mankiw’s formula, we would expect a fed funds rate of 4.86% right now.

It’s not even close. Last week, the Fed raised the rate to the 1.0% to 1.25% range.

Even the most hawkish FOMC voter (whoever it is) doesn’t foresee rates touching 4% before 2019. And all the others predicted much lower rates than that.

Clearly, this means the rules have changed.

Faith vs. Data

Just to make all this crazier, many folks think the Fed shouldn’t raise rates at all when core inflation is so low.

The real reason Yellen and others want to raise rates: they want to be able to cut rates in the next recession without going below zero.

In other words, they need breathing room. But acquiring it may bring on the very recession they’re preparing for.

Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari disagreed with last week’s decision and explained why in a long blog post. Here’s his main point:

For me, deciding whether to raise rates or hold steady came down to a tension between faith and data.

On one hand, intuitively, I am inclined to believe in the logic of the Phillips curve: A tight labor market should lead to competition for workers, which should lead to higher wages. Eventually, firms will have to pass some of those costs on to their customers, which should lead to higher inflation. That makes intuitive sense. That’s the faith part.

On the other hand, unfortunately, the data aren’t supporting this story, with the FOMC coming up short on its inflation target for many years in a row, and now with core inflation actually falling even as the labor market is tightening. If we base our outlook for inflation on these actual data, we shouldn’t have raised rates this week. Instead, we should have waited to see if the recent drop in inflation is transitory to ensure that we are fulfilling our inflation mandate.

Kashkari considers the risk of above-2% inflation returning to be low - and manageable even if it happens.

Looking at history, he does have a point. Here’s core PCE going back to 1960.

From the late 1960s to the mid-1990s, inflation remained above 2%. Of course, even 2% inflation can be detrimental - sustained for 20 years, it will consume about one-third of your dollar’s buying power. Luckily, it’s ranged below that for most of the last two decades (with the exception of 2005–2008) and seems likely to stay that way.

But why are we even having this argument?

Algorithmic Central Banking?

We talk all the time about robots taking our jobs. Could they take the Fed’s job?

Presently, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) spends thousands of work hours trying to solve the same problem Professor Mankiw’s equation answers in about one minute.

Some economists think the Fed should just follow fixed rules - not necessarily Mankiw’s formula, but something like it. Put rates on autopilot and get out of the way.

An attractive idea that might even yield better results. But, much like a plane’s autopilot, we need at least one skilled human aboard to take the stick if necessary.

The output - that is, monetary policy rules - would highly depend on the input. Incorrect inflation or unemployment data might produce unexpected results.

President Trump hasn’t yet nominated anyone for the three vacant Fed seats, so a whole different crew could be in charge next year.

Meanwhile, names floating around to replace Janet Yellen include advocates of rules-based policymaking. A recent Bloomberg survey of economists pegged Stanford economist John Taylor, author of the “Taylor Rule,” as a likely candidate for the job. Mankiw got a few votes too.

But whoever occupies the top seat, they will still need a transition plan. An overnight jump from today’s 1% range to nearly 5% would be disruptive, to say the least.

That leaves us back at the same conclusion. We live in a time of maximum monetary uncertainty. US interest rates drive the US dollar, which in turn drives just about every financial market on the globe. It’s that important.

For example, dividend-paying US stocks will be relatively less attractive if new Fed policies drive long-term interest rates higher. But they could also gain value if bond yields move lower. What do you do?

I look for income-generating investments that can adjust to fast-changing conditions. They exist, if you have an open mind and know where to look.

Only one thing is sure in this transition: Anything can happen - so be ready for anything.

-------------------------------

*Patrick Watson is senior economic analyst at Mauldin Economics. This article is from a regular Mauldin Economics series called Connecting the Dots. It first appeared here and is used by interest.co.nz with permission.

8 Comments

It is a good thing that no one would ever study the rules these robots use in an effort to manipulate the automatically set rate

Just interested in why Patrick Watson thinks inflation of even 2% is bad? I'm pretty sure you need a certain level of inflation to maintain spending, investment and money velocity, and avoid deflationary spirals. https://www.khanacademy.org/economics-finance-domain/core-finance/infla…

Also, this vid on automation might be of interest. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WSKi8HfcxEk

I'm pretty sure you need a certain level of inflation to maintain spending, investment and money velocity.That's a con job you've fallen for! What "maintain spending, investment and money velocity" needs is....productivity increases...and that, funnily enough is exemplified in....tada! FALLING PRICES. The more efficient we get, the lower prices should be.

I mostly ignore consumer inflation as it isn't very important to me. Asset inflation running at 10-20% is far more concerning.

One can't ever remove the need for prudent judgement - and robots can't do that sort of thing.

What basis do you have for suggesting Artificial Intelligence won't be able to do that?

Worth trying to define "prudent judgement" first, I reckon.

There'll be an algorithm for that

There is very little that robotics will not be able to do, and because of what we are, no matter the consequences, we will never curb our curiosity about exactly what we can do. Done right robotics and technology could the saviour of the planet and us.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.