By Kirk Hope

Covered bonds have found favour with issuers and investors around the world since the global financial crisis.

For investors they provide dual recourse through a secured interest in a pool of loans provided for in a special purpose vehicle (the cover pool), as well as an unsecured claim on the bank to the extent that the cover pool cannot meet a claim. For issuers they allow access to cheaper and more stable long-term funding from wholesale debt markets.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has noted that “covered bonds are common internationally, with total outstanding issuance being in excess of €2 trillion. European issuers are the largest issuers, and covered bonds are one of the larger asset sectors in the European bond market. Around 300 institutions in over 30 countries have issued covered bonds. The bulk of covered bonds, around 90 per cent, have been issued by countries in the euro area, though firms have recently started to do so in some other countries. In the euro area, the covered bond market is roughly 40 per cent of the size of the sovereign bond market.”

Covered bonds have been used in Europe since the mid-eighteenth century. Banks in France, Spain, and Italy issue covered bonds under a legislative framework. The United Kingdom recently put in place a legislative framework for covered bonds. They are also gaining in popularity outside Europe, not only in New Zealand, but also in Australia, Canada and the United States.

A number of New Zealand banks have developed covered bond programmes, and the government has recently introduced The Reserve Bank (Covered Bonds) Amendment Bill to provide legal certainty as to the treatment of cover pool assets in the event that an issuing bank is placed into liquidation or statutory management.

This will bring us into line with other jurisdictions and means that New Zealand covered bond issues are not at a competitive disadvantage.

The position in Australia is that until 2011 Australian authorised deposit taking institutions (ADIs) were not permitted to issue covered bonds because covered bondholders would have preferential access to an ADI’s assets, thereby subordinating other unsecured creditors, such as ordinary depositors.

This would conflict with the Banking Act 1959, which enshrines the principle of depositor preference under which, if an ADI is wound up, all of its assets in Australia are made available to meet the ADI’s deposit liabilities in Australia in priority to other liabilities of the ADI.

However, in 2011 the Australian government enacted legislation to provide a regulatory framework to address those issues and allow for covered bond issuance. Australian Treasurer Wayne Swan stated at the time that the law change was “a critical economic reform” that would strengthen the Australian financial system, increase the supply of credit, and provide cheaper, more stable and longer term funding for banks, building societies and credit unions.

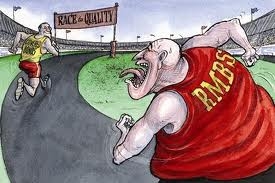

One of the issues often raised with covered bonds is the priority that bondholders get over depositors and other creditors in the event of default.

Regulators have tended to manage the subordination of depositors and other creditors by setting limits on the issuance of covered bonds. Regulations in Canada and rules proposed in the US Covered Bond Act limit covered bond issuance to four per cent of a deposit-taker’s assets (in Canada) or liabilities (in the United States). In Australia covered bond issuance is limited to 8 per cent of the ADI’s assets.

Formal issuance caps have also been prescribed in the United Kingdom; the UK Financial Services Authority discusses all covered bond and other ‘asset encumbrance’ plans with issuers and can impose both issuance caps and higher capital charges.

Here, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand has imposed a ten per cent limit on the issuance of covered bonds by locally incorporated registered banks by including this as a condition of registration.

A subset issue which is dealt with by the regulatory cap is the issue of overcollateralization of the cover pool. Overcollateralization refers to the additional loans that need to sit in the pool to ensure compliance with minimum cover pool requirements.

While ratings agencies and some regulators require overcollateralization of the pool, this is restricted by the imposition of the regulatory cap; total loans in the pool cannot exceed the regulatory cap.

Covered bonds are a welcome addition to the New Zealand market. They extend our banks’ access to cheaper more stable longer term offshore funding. They also give investors the confidence to continue to provide essential funding to help facilitate growth which New Zealand needs for both the Canterbury rebuild and our wider economic recovery.

*Kirk Hope is chief executive of the New Zealand Bankers' Association.

4 Comments

Covered bonds have found favour with issuers and investors around the world since the global financial crisis.

Yes, until they don't.

I suggest you acquaint yourself with the shadow banking system and come back when you understand how the securitisation of bank assets financed by repurchase agreements play an important role in the continuing financial crisis.

What will it mean to the status and consequent stability of the New Zealand banking system when a foreign RP lending counterparty publicly rejects any tranche of NZ sourced covered bonds as acceptable collateral?

Could the foreign branches of the same name local covered bond issuers be RP financing their own debt in Europe for their own gain? Not impossible, right? - off-balance sheet as well?

Karl,

I was wondering how anyone could write such rubbish until i saw you were head of the bankers association. if you guys are so interested in stimulating lending to boost productivity, why dont you actually lend to businesses anymore??? Covered bonds exist to provide banks a cheaper and easier source of funding - no surprises that you will park most of the dosh into housing. As you well know, covered bonds provide stability for the INVESTOR, they add risk for the DEPOSIT HOLDER. Without a consequent rise in rates to deposit holders, CBs essentially SOCIALISE the risk onto those not previously required to bear it. Here is a simple principle that should be added to all Banking 101 classes - Financial engineering does not eliminate risk, it relocates it.

... and as for bringing us in line with other jurisdictions, would any of those be European by any chance?

Jimmy, the author's name is Kirk.

There must be an echo... from the other thread:

Some things don't need/can't take evolution/innovation. For example double entry book keeping, loan finance, where innovation/evolution has been confused with say criminal activity. (SCF - although KH may say nothing proven yet/let them have their day in court, aside from investors lives in ruin...) Somethings can only innovate to 100%.

The "innovation" here is the letting new "investors" rank ahead of existing. More a neat trick we say...

Think about whom is doing the "letting", and as they say in Hollywood, "Whats my motivation?"

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.