By Jared Dillian*

By this point you have probably heard that $15 trillion of bonds are trading with negative yields, which represents 25% of all sovereign bonds outstanding. Lots of people are indignant about this—but it’s no use getting mad at the market.

Lots of people say it doesn’t make sense. It makes sense to me, and to a few other people. If you see something in the market that doesn’t make sense, it’s usually best to stay away, rather than picking a fight with it.

We’re not in uncharted territory here. Let’s do a market psychology exercise.

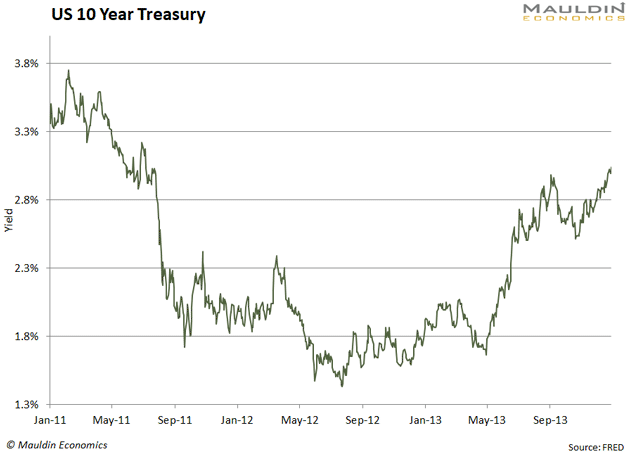

Back in 2012, ten-year yields were actually lower:

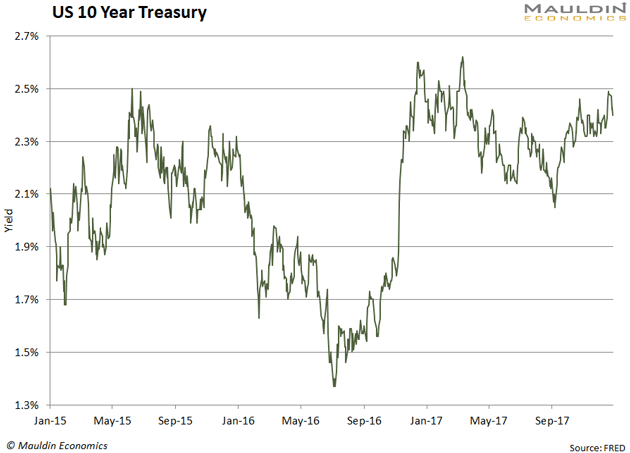

And again in 2016:

Both of those times (and I remember this quite clearly), people were bullish on bonds and said that yields were going lower. Instead, they rocketed higher. They said that the deflation/disinflation that we were experiencing was unstoppable, and a whole bunch of other stuff, that turned out not to happen.

In 2016 I presented a short bond thesis at a conference and I practically got hounded off the stage. Nobody remembers this, but everyone was really bullish on bonds back then. It was actually kind of a weird situation. The organizers of the conference avoided me after that, like I was radioactive.

Now practically nobody is bullish! Why is that? I suppose the inflation picture is markedly different—we have tariffs and there are wage pressures and such—but I don’t think that’s what this is about.

My thesis, which I have carried around for 20 years: when everyone believes something, it is usually wrong.

What does everyone believe right now? That negative yields are unsustainable.

Maybe that is true. Maybe not.

Bubbles in everything

You can have a bubble in any asset class, from little stuffed animals to lines of computer code. Why not bonds?

The bitcoin bubble burst when there were more Coinbase accounts than Schwab accounts, and there was a bitcoin rapper in the New York Times. We don’t have any bond rappers yet, so I’d say the bull market has a ways to go.

George Soros always said that if he saw a bubble forming he would get in there and try to make it bigger—which is pretty much the opposite of what everyone does.

What everyone does, is goes on Twitter to complain about it. It’s not just Twitter—negative yields was probably the biggest concern you guys listed in the bond survey.

Right now, people don’t believe in the trade, or understand it. This is going to continue until they do understand it.

There are also fundamental reasons which are plainly obvious—bad demographics and a savings glut, which creates huge demand for safer assets like bonds, pushing down yields. Both of those things were cited the last two times around (2012 and 2016), but not this time.

My opinion: smart people (including the owner of this website) predicted debt and deflation years ago. You know how it happens. Gradually, then suddenly.

Anyway, I can’t do one scroll through Twitter without someone freaking out about negative interest rates. Turn on the internet and see. But what if negative interest rates… are normal? What if they make sense?

Ask this question around certain people and they completely lose their minds. The last time I saw people get this indignant about a trade, it was… Beyond Meat. See how that turned out. I have experience with this sentiment thing. When something makes people angry, I have confidence that the trend in question will continue for a very long time. I think negative rates are not an aberration and could become a semi-permanent feature of finance.

When people start to believe in negative rates, they will probably come to an end.

Bond house

Lehman Brothers was a “bond house.” They were really good at fixed income—not so good at equities. Though equities did pretty well towards the end.

It was kind of hard not to be exposed to bonds at Lehman, even if you did work in equities. If you recall, the Barclays bond indices that we have today used to be Lehman bond indices. I got a lot of customer flow in the 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF, TLT, and it was because Lehman had the index.

I also took six weeks of bond math when I joined the firm in the summer of 2001, and most of it stuck with me.

A lot has changed since then. Most of the trading activity in US Treasurys is electronic. Back then, it was all high-touch—carried out by actual humans.

A lot has remained the same. It’s still fundamentally the same market that it was 20 years ago. There’s a lot more debt, but one thing that has remained constant is how difficult it is to trade off of supply—the idea that more bonds makes rates go higher. And, people believe strange things about the bond market these days—they think more supply makes interest rates go down.

If you think things are stupid, they will probably get more stupid. You can put that on my tombstone.

*This article by Jared Dillian of Mauldin Economics was first published by Mauldin Economics here. It is used with permission.

4 Comments

Bring back market balanced risk/reward to democracy and capitalism. Anything else is central planning, which always fails. If you removed state sponsored institutional participation out of any market other than govt debt issue, there could be no negative rates. Not angry, just realistic.

Hmmmm. lots of words but not much of an explanation

Lets take note of two recent revelations concerning banks:

The CEOs of nearly 200 companies just said shareholder value is no longer their main objective

Well they would, wouldn't they?

If only you had enough pristine collateral sitting idle on your balance sheet where you could substitute that unassailable security in repo and therefore maintain the funding you need in order to bury that illiquid monster somewhere on the balance sheet until the storm passes – and its value goes back to up to reflect a more reasonable and fundamental level. That substitution ability buys you the most valuable thing in a crisis – time.What lesson might all of the global banking system have learned here? Simple. You better have some UST’s lying around on your balance sheet, a lot of them potentially, in case things turn in illiquid markets again. You can’t risk being caught without what are, essentially, repo reserves. Not bank reserves but collateral reserves.That’s what UST’s are, or German bunds overseas in Europe; they are balance sheet tools and it truly doesn’t matter what their return might be. The credit characteristics of the US government don’t make a bit of difference. You hold them in inventory because of only their liquidity characteristics. Link

.

The author misses a very important macro-prudential development post-GFC - banks now have to hold HQLA as part of their LCR calculation and final salary pension funds have had to de-risk. CBA alone holds $95b ACGB and Semi's and $45b of lesser rated FI, this structural bid has kept a lid on yields.

Short of a full blown debt default if ZBs would actually allow a deflationary recession, negative yields are the humane way out of debts that can not possibly be repaid...and this is just the beginning of the cycle.

From a sovereign perspective, issuing debt with negative yields forces inflation as nominal GDP rises. A logical continuum, debts diminish slowly through inflation.

Unfortunately, it also wipes out savings, if careless, and drives currencies down

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.