This article is a re-post from Fathom Consulting's Thank Fathom its Friday: "A sideways look at economics". It is here with permission

Last Saturday, Liverpool, the most successful club in British football,[1]won their sixth Champions League title beating Tottenham Hotspur in the final.

As a Liverpool fan, and the son of a Spurs fan, the victory was particularly sweet. In response to his team’s loss, my dad suggested that “losing isn’t so bad, it might pressure Daniel Levy [Tottenham Hotspur Chairman] to spend this summer”.

While both champion and runner-up earn a financial windfall from their progress in the competition (Madrid and Liverpool received €88 million and €81 million respectively in the 2017/18 season), the heartbreaking disappointment of coming within touching distance of the ultimate prize in European football may motivate tight-fisted owners to open the purse strings.

But does this hold? Do the Champions League runners-up spend more than the champions in the following year?[2]

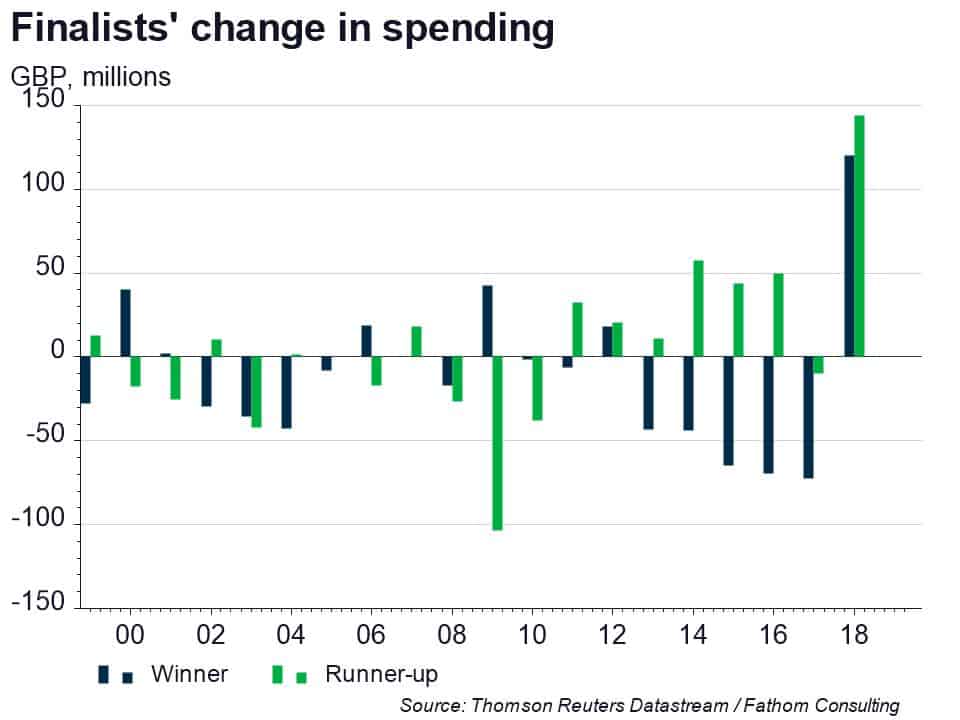

The relationship isn’t quite as clear-cut as we might expect. Before the 2010/11 season, clubs losing in the final would, on average, spend significantly less than they did in the previous season. However, since the 2010/11 season the trend has reversed, and clubs who lose in the final are spending significantly more on average than they did in the previous season.

The largest increase in net spending was that of Liverpool: a £144 million rise from 2016/17 to 2017/18.[3] There were two main factors: a large transfer surplus in 2017 due to the sale of Phillipe Coutinho for a reported £122 million to Barcelona, and the £164 million spent in the summer of 2018. The greatest decline in net spending was £103 million from 2007/08 to 2008/09 when, after losing to Barcelona, Manchester United reluctantly sold Cristiano Ronaldo to Real Madrid for a world-record transfer fee of £85 million.

But only two of the eleven clubs who invested extra cash won the Champions League in the following year (Bayern Munich and Liverpool). The others effectively doubled down on their losses.

In contrast to the losers, the winners in the final spend £12 million less on average than they did in the previous season. The pattern is particularly pronounced since 2010/11 when they have on average spent £20 million less than in the previous season.

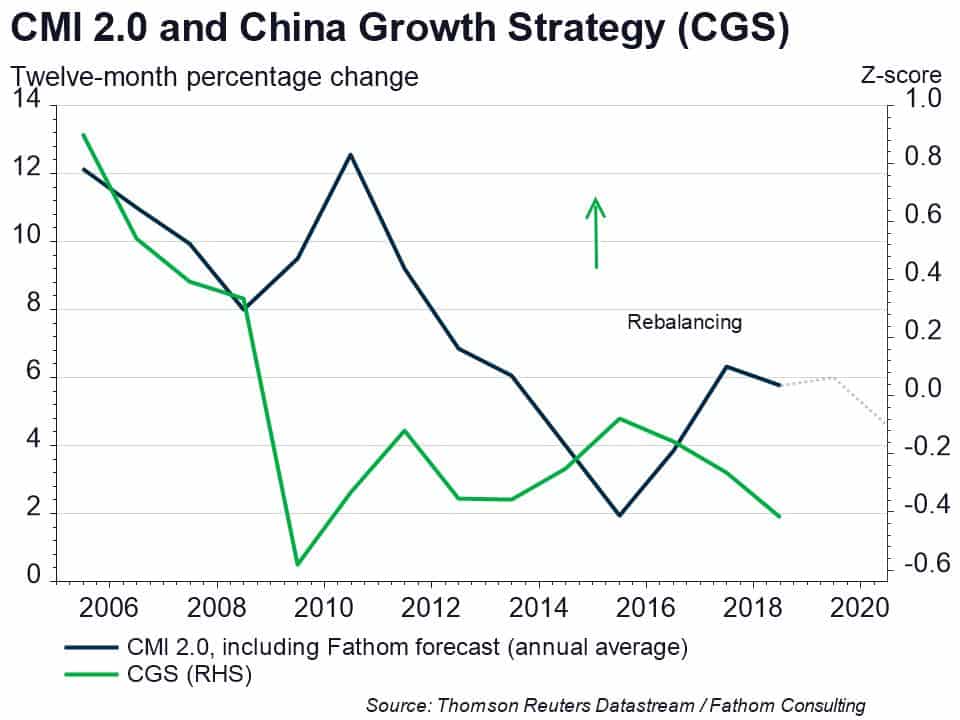

There are parallels here with Chinese policymakers who respond to poor economic performance by increasing credit growth to fuel investment and depreciating their currency to support exports — the ‘old growth model’. Fathom’s China Momentum Indicator (CMI) and China Growth Strategy (CGS) indicators show that every time growth slows, policymakers turn on the taps.

But perhaps China should listen to the warning signs from Manchester United. Since the departure of Sir Alex Ferguson, they have underperformed on both domestic and international fronts despite numerous expensive forays into the transfer market.

Much like United, policymakers in China are experiencing diminishing marginal returns from doubling down on the old growth strategy. Like Manchester United, this strategy was successful in the past — during the financial crisis it helped offset the impact of weaker global growth and trade on China’s economy — but it’s unlikely to be as successful now as the forces of gravity act to slow growth.

To achieve sustainable growth in the long run, China needs to try something new — it must rebalance away from the old growth model and move towards a more consumer-oriented economy. However, we see this outcome as unlikely to happen and our latest quarterly forecast (out next week) shows China’s economic growth, according to our CMI, drifting towards 4% as it suffers ‘Japanification’. But, in a world where Jordan Henderson can lift the Champions League Cup, anything is possible.

[1] While the author notes that Manchester United have won more league titles than Liverpool, it is his opinion that Liverpool’s six Champions League titles relative to Manchester United’s three makes Liverpool the more successful club.

[2] Andrew Harris reported in a previous blog that money spent on wages can buy you success in the Football League. While the excellence of his analysis is eternal, his first footnote hasn’t aged well…

[3] The amount spent after losing a Champions League final is calculated using a comprehensive database created by ewenme on Github. The database contains all football transfers in Europe’s top leagues since 1997.

Greg Spanner is an economist at Fathom Consulting in London, England. This article is a re-post from Fathom Consulting's Thank Fathom its Friday: "A sideways look at economics". It is here with permission

4 Comments

""[1] While the author notes that Manchester United have won more league titles than Liverpool, it is his opinion that Liverpool’s six Champions League titles relative to Manchester United’s three makes Liverpool the more successful club.""

A very dubious definition of success. Surely the purpose of a football team is to attain slave like blind devotion from its fans. On that basis Glasgow Rangers is easily the most successful sports team in recorded history with support almost as fanatical as the the incompetance of their selection of cloggers. (Apologies if they have improved since I left Scotland). On the other hand success could be defined as what is achieved with the resources available - and then go no farther than Jock Stein's Celtic (or maybe that Bolton FA cup winning team of the 1950's where all players were locals paid the 5 pound signing on fee).

Relevence to China - none.

Does anyone know how many tri-nations the Allblacks have won? Nope its only the world cups that count.

Lisa Carrington's world cup golds? Olympic medals?

Success always seems to be attributed to the biggest stage

As a long time Liverpool fan (since 1965) recent events have been very welcome indeed. One should note that there has been long periods between the short sweet taste of success(es) but as is opined above, it has nothing to do with China.

When you play capitalism you need to factor in the fact that you won't always win. When you do, that's great, but rust never sleeps as they say, & tomorrow will be slightly different from today, so take nothing for granted. How does that effect China? China has to learn how to lose before it can win, that's the story of life regardless of which culture or time period you live in. Some may say well, China lost in the first half of the 20th Century. A quick look will tell you we all lost in the first half of the 20th Century. It was a time of chaos pretty much everywhere. America went bust 11 years ago. They called it the Great Recession for a reason. For them, it was. There were almost 7 million foreclosures on homes owned by ordinary people. That hurt them. They are stronger today as a result. Is China? Well, last time (2008) they created cash & we all got through. This time they're creating cash because that's all they know what to do, but the ending will be slightly different for this episode.

A comparison stretched beyond breaking point, IMHO. China's 'growth' (in quotes because almost every economic statistic is suspect) is a combination of adoption of technology (capitalism with Chinese characteristics - they have the Social Credit Score, we have Alexa....) and the entry into a counted, cash economy of hundreds of millions of former subsistence farmers. Hard to estimate the actual historic contribution of each, as it will have changed each year, but one thing is for sure. China is running out of subsistence farmers to convert, out of children for the next generation, and out of technology that's easy to adopt (or to appropriate). S-curves, all, and China is starting to plateau on all these three counts: the days of the rapid ascent up the straight bit of the S are over.

Brit football? Pffft......

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.