Government seriously considered not extending the deposit guarantee scheme past October 2010, a Treasury paper shows. Treasury recommended to the government an extension of the scheme, but said the decision between either tightening the scheme and extending it until December 2011, or keeping the status quo and allowing it to expire in October 2010, was "finely balanced".

If it were not extended and there were defaults under the scheme before October 2010, depressed asset prices would lead to reduced recovery rates and therefore lead to an increase in costs faced by the Crown, Treasury said. However Treasury said ending the scheme early also removed some moral hazard risks and would remove a further period of economic distortion.

Finance companies gathered an extra NZ$880 million into their accounts under the existing scheme after it was introduced in October last year, while fees paid by institutions covered by the scheme currently totaled NZ$87.4 million per annum, with NZ$81.9 million of this paid by banks.

The Treasury paper set out pros and cons of extending the scheme or not, finally settling on an extension with tightened criteria which was passed by Parliament under urgency on Wednesday morning.

Treasury warned that if the scheme expiring in October 2010 resulted in "concentration of defaults in the lead up to the end of the guarantee period, then that could also lead to assets being realized over a short period, depressing asset prices and reducing recovery rates and so increasing the net cost to the Crown of the default event."

"This is because the gross payments to deposit-holders, less net assets subsequently recovered from the deposit-taker could be expected to be higher, than if the default event occurred when asset prices had stabilised, or were recovering," Treasury said.

"However, this would be offset to some extent by the additional fee revenue that would be collected during the additional period, from firms in the DGS," it said.

Treasury said its preferred option, if the scheme were to be extended, would be to extend the scheme with tighter terms in order to achieve a less disruptive and potentially less costly exit from the DGS.

"The decision of whether to extend the DGS until 31 December 2011 on tighter terms or proceed with the status quo of exiting in October 2010 is finely balanced," Treasury said.

"The gains to system-wide financial stability from continuing the scheme, or detriments of the scheme lapsing are not large because it is only the relatively small institutions that are materially at risk," it said.

"However, the risk of deposit flight to Australia is lower under the extended DGS, as it more closely aligns the end date of the DGS with that of the Australian guarantee scheme, although this overall risk is considered low."

"Given possible enhancements to an extended scheme, the economic efficiency arguments are finely balanced. The strongest argument is that extending the scheme reduces likely fiscal and economic costs of guaranteed firms failing by extending adjustment over a longer period, so it is more likely to improve recoveries and avoid depressing an already fragile asset market."

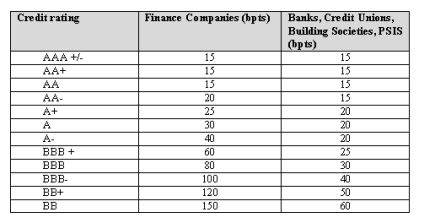

The extended guarantee scheme tightened entry criteria, with firms required to have a credit rating of BB or better, if they wish to enter the scheme from October 2010. Treasury said risks arose from the new fee structure that would be imposed for the extension of the scheme, which may hit firms that would be viable in the long-run, but that faced struggles in the short-run.

The Treasury paper also noted that finance companies had grown their deposit books by NZ$880 million, or 19%, since the guarantee was introduced in October last year. Finance companies with deposit books under NZ$5 billion when the scheme was introduced were only charged fees for the guarantee on the expansion of their loan books.

To date, fees collected under the current scheme were NZ$87.4 million per annum, with NZ$81.9 million of this coming from banks and NZ$5.5 million from non-banks, Treasury said.

The extended scheme with its tightened criteria would see the fee structure changed to make it cheaper for institutions with higher credit ratings to be included in the scheme, and more expensive for institutions with lower credit ratings.

"In determining the fees, some consideration has also been given to affordability issues for non-bank deposit takers (although the primary consideration was to reduce economic distortions). A risk here is that non-bank deposit takers are unable to afford the fees (or attract and retain deposits without the guarantee)," Treasury said.

"While viable in the long run, some institutions may struggle to be viable in the short run as they adjust to the new prudential requirements and are subject to the more commercial fees schedule. The proposed fee structure takes this concern into account, but the risk that some institutions that are viable in the long-run will experience considerable difficulties in the short-run remains, particularly in respect of building societies."

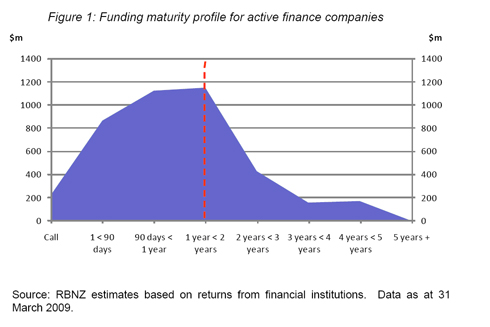

Treasury's leaning to the extension of the guarantee was also partly down to the "wall" of maturities faced by finance companies in October 2010.

"(T)he impending expiry of the current DGS has resulted in short-term "hot money" seeking higher returns, and a dramatic "wall" of maturities is building up for many NBDTs as investors wait to see if the guarantee will be extended post October 2010. In general this wall of maturities is making it difficult for NBDTs (includes finance companies) to lend for term, and could result in liquidity problems for some NBDTs if they find it difficult to attract retail funding after the guarantee expires."

"In determining the fees, some consideration has also been given to affordability issues for non-bank deposit takers (although the primary consideration was to reduce economic distortions). A risk here is that non-bank deposit takers are unable to afford the fees (or attract and retain deposits without the guarantee)," Treasury said.

"While viable in the long run, some institutions may struggle to be viable in the short run as they adjust to the new prudential requirements and are subject to the more commercial fees schedule. The proposed fee structure takes this concern into account, but the risk that some institutions that are viable in the long-run will experience considerable difficulties in the short-run remains, particularly in respect of building societies."

Treasury's leaning to the extension of the guarantee was also partly down to the "wall" of maturities faced by finance companies in October 2010.

"(T)he impending expiry of the current DGS has resulted in short-term "hot money" seeking higher returns, and a dramatic "wall" of maturities is building up for many NBDTs as investors wait to see if the guarantee will be extended post October 2010. In general this wall of maturities is making it difficult for NBDTs (includes finance companies) to lend for term, and could result in liquidity problems for some NBDTs if they find it difficult to attract retail funding after the guarantee expires."

Treasury detailed the benefits of ending the scheme early.

Treasury detailed the benefits of ending the scheme early.

Economic distortions include encouraging guaranteed depositors and deposit taking institutions to make riskier investment decisions since gains are privatized and losses are socialised (referred to as a "moral hazard" problem); lessening the market incentives on firms to restructure, merge, exit the industry etc; and creating an artificial shortening of terms offered by firms if depositors are not willing to invest beyond the guarantee period. Allowing the DGS to lapse avoids the additional period of economic distortion. Moreover, the DGS ceasing in October 2010 Stability is aided to the extent that moral hazard is reduced, thus decreasing the likelihood of more failure in the long run through imprudent lending. However, there are more likely short term stability detriments, which are considered in the cons section. It can be expected that individuals would take actions that would reduce their own risks, which would also have systemic benefits, but in aggregate may not be sufficient. Letting the DGS cease in October 2010 would avoid the direct costs associated with the Treasury continuing to operate the DGS for an additional period, but forgo the fees currently collected. Also, retail guarantees expose taxpayers to risks of default. Allowing the scheme to lapse removes this risk. However, in the transition it could create larger expected fiscal costs if it causes institutions to fail at a time when asset markets are still weak.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.