By Rod Vaughan

Since last week’s LawNews story voicing the concerns of lawyers and academics worried about potential curbs on freedom of speech and the likely unintended consequences of the proposed new law, others have joined the fray.

ADLS’ Criminal Law committee strongly opposes the government’s plans, with two of its members, both senior criminal QCs, urging politicians and the Ministry of Justice to back off.

Committee convenor and ADLS President Marie Dyhrberg QC describes the proposed censorship as “a bucket of cold water on the kindling of our democracy.

“Are we such a juvenile society that we require the rule of law to make our political discourse safe enough and decent enough to handle?” she asks. “Or do we have the collective intelligence and integrity to prove ourselves worthy of freedom?”

Julie-Anne Kincade QC, another committee member and a member of the ADLS Council, questions the government’s ability to cure the divisiveness in society by such a “knee-jerk, navel-gazing response”.

“We must think about these laws beyond a politician’s soundbite and pat on the back,” she says.

“The Ministry of Justice proposal says the new laws seek to protect ‘our values of inclusiveness and diversity’ but without proper investment in education, community outreach and reducing inequities and marginalisation on all fronts, we cannot proudly and truthfully say that these are the government’s values.

“It is unclear that the policy is descriptive enough to be effective practically. The government has spoken of combatting terrorism with these laws, but terrorism’s causes are much more multi-dimensional than hate speech. People start chatting in dangerous online communities in the first place for reasons that go deep into the nature of politics and society.

“When I think about [examples of speech inciting violence throughout history], the most harmful, insidious hate speech is actually spoken by those in power. How do you legislate against that? The government seems to want to encourage ‘social cohesion’ with these new laws, but this sort of thing cannot be forced. Social cohesion is fostered not only by education and community outreach but also by protection of freedom of speech, a right to protest and [demonstrate] legitimate anger, and a right to private and intimate conversation.

“A national crisis such as terrorism needs to be responded to with clarity in the law. The government should not fall into the trap of passing questionable and controversial policies while citizens are too distracted to engage and develop an adequate response,” Kincade says.

Another committee member, barrister Iswari Jayanandan, says there is no reason to believe the widening of our hate speech laws won’t have the same results as similar legislation in the UK, where people have been jailed under the Public Order Act 1986 and the Communications Act 2003.

Commonly known as the ‘stirring up’ law, a hate speech offence under the Public Order Act includes inciting racial hatred or stirring up hatred on the grounds of religion or sexual orientation. Section 127 of the Communications Act makes it an offence to send an ‘indecent, obscene, or menacing’ message over a public electronic communications network.

Recent cases in the UK highlight some of the key flaws within the legislation, she says. In 2014, a 21-year-old man was jailed for six weeks for posting an ‘inappropriate’ comment on a Facebook news article about the stabbing of a local school teacher. He was charged under the Communications Act with “having sent by means of a public electronic communications network a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing nature”. A month later, another man was imprisoned for eight weeks for his online comments regarding the same article.

Lawyers and human rights campaigners in the UK have raised concerns about the number of people who have been jailed simply for causing ‘offence’. The big issue is whose definition of ‘hate’ and ‘offence’ is used to prosecute people since no definition exists under international law. Will we be arresting and jailing people simply for making tasteless remarks?

Jayanandan says because our legislators, as in the UK, want to leave the police to interpret the meaning of ‘hatred’, this could result in unfair pressure to prosecute all instances of ‘hate.’ “We have seen a similar thing happen with the family violence and sexual offending policies,” she says.

Logical move

Of those spoken to by LawNews, the Dean of the Auckland Law School, Professor Penelope Mathew, was the most upbeat about the proposed legislation.

Speaking as an academic and not as a representative of the law school, Mathew endorsed the idea of removing hate speech from the Human Rights Act and place it into the Crimes Act, saying it is “logical and in line with the recommendations of the Royal Commission.

“The new offence would make it a crime to intentionally stir up or maintain or normalise hatred against groups defined by protected characteristics through being threatening, abusive or insulting, including by inciting violence.

“This seems a reasonable approach to test the intended outcome of the recommendation of the Royal Commission by asking the public whether it thinks the change will indeed produce that outcome.”

So what is her take on Opposition parties who have condemned plans to make hate speech a criminal offence and introduce harsher penalties?

ACT leader David Seymour has condemned the legislation as “a huge win for cancel culture which will create an even more divided society”.

But Mathew says Seymour’s comments ignore the fact that the proposals seek to alter legislation that pre-dates so-called cancel culture and that the legislation reflects international laws which New Zealand and the vast majority of the rest of the world have accepted.

“These laws were not inspired by cancel culture but by the very real and ghastly experience of the Holocaust, when human beings were murdered on the basis of characteristics that they could not and/or should not have had to change and Nazi propaganda fuelled these crimes.

“The attempt to respond to the Christchurch killings and the role of social media in that event can hardly be dismissed as cancel culture.”

But what exactly is the proposed legislation trying to fix, given the Christchurch killings were not triggered by hate speech but by the actions of someone who was already radicalised?

“The Christchurch killer livestreamed his actions, which could inspire copycat actions and may in fact have done so,” Mathew says.

“The Royal Commission discussed research regarding the way that radicalisation and acceptance of violence can occur through participation in groups, including online, where extremist material and role models are found. The commission also discussed the Christchurch killer’s own online activities and noted the plausibility that his accessing of extremist content contributed to his actions on 15 March 2019.

“The legislation is clearly trying to meet the challenge identified by the Royal Commission to develop appropriate responses to harmful behaviours which are effective in limiting their occurrence and frequency but which do not, at the same time, exacerbate divisions.”

But on the vexed question of how hate speech might properly be defined, Mathew concedes that it’s a tricky area.

“It certainly is a fraught issue. The government is explicitly asking for feedback on many aspects of the proposals, including the proposal to use the word ‘hatred’ and whether this will be easier to understand.

“I suspect hatred will be more easily understood and viewed as a relatively high threshold as compared with hostility, ill-will, contempt and ridicule. Ultimately, however, people need to understand what harms are caused by hate speech, the limitations to the normal position in a democracy that speech is best met by more speech, and the problems posed for democracy by speech that marginalises groups based on characteristics such as race or religion. That is a task for education.”

Problematic language

Dr Jane Calderwell Norton, a senior lecturer at the Auckland Law School with a special interest in discrimination law, is concerned that defining hate speech will prove to be an almost impossible task.

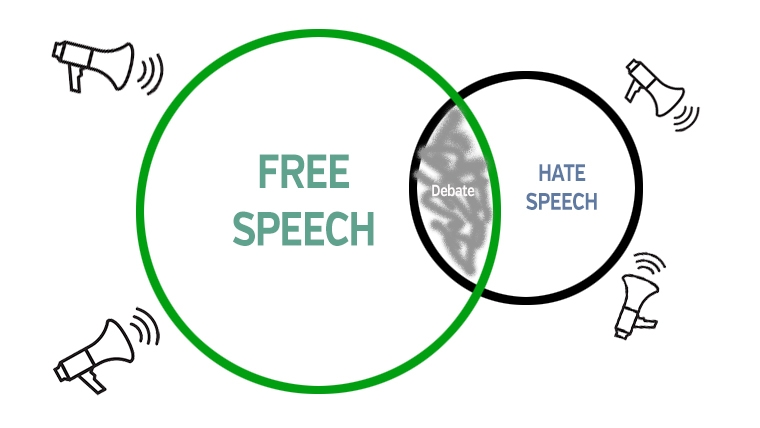

“The legislation does not have a concise and unambiguous definition of hate speech,” she says. “I am not sure one is possible since human language changes and intention, meaning and impact depend on the context, and one person’s hate speech is another person’s political opinion.

“I have concerns about the proposed legislation because it continues to use problematic language such as whether the words are ‘insulting’. If hate speech is about preventing harm to people, any hate speech legislation needs to be carefully crafted so that it doesn’t capture unpopular or offensive speech that does not cause serious harm.”

Calderwell Norton agrees with many other commentators who refute suggestions that the Christchurch mosque terror attack was triggered by hate speech. “I am not clear how expanding our criminal hate speech provisions would have prevented the mosque terror attacks. It can also be the case that hate speech prosecutions can turn a person into a martyr and further radicalise their followers who think there must be truth to what the person is saying if the government is trying to shut it down. This has been the case overseas.”

She says freedom of expression has been a hard-won right with many countries still not allowing it, singling out religion as a case in point. “I do have some reservations about any criminal offence that potentially prevents people from criticising religion. There have been cases in Europe where people have been criminally convicted or had their films and artwork seized because they have insulted a religious figure.

“I worry about hate speech legislation being used to prevent people from criticising religion or religious leaders. However, given that the proposal looks to expand hate speech coverage to sexuality and gender, religious leaders who preach against gender fluidity or homosexuality could also be caught up in this criminal provision.

“It could also make religious holy texts that criticise other religion and their adherents unlawful. Any new legislation would need to be carefully crafted so it protects religious groups and individuals from harm but doesn’t capture expression that is important in any democracy, such as the criticism of religious ideas.’

Social and political commentator Karl du Fresne says there are so many things wrong with the proposed laws that it’s hard to know where to start.

“But let’s begin with an obvious problem: those words ‘hate’ and ‘hatred’. Politicians and activists toss these words around as if they have some agreed, settled meaning, but they don’t. What to one person might be a valid and reasonable comment, or even a mere question relating to ethnicity, religion or gender identity, might be construed by an over-sensitive ‘victim’ as hateful.”

Du Fresne says a similar problem arises with other language used in the government’s ‘tortuously wordy’ discussion paper. “Terms such as ‘threatening’, ‘abusive’, ‘insulting’, ‘inciting’ and ‘stirring up’ are highly subjective and liable to be interpreted in different ways, depending on who’s doing the interpreting.

“There’s also the scary prospect that with the criminalisation of ‘hate speech’, it would fall to the police – initially, at least – to determine which opinions cross the legal threshold. We have ample evidence from Britain of the dangers that arise when the police are politicised and over-zealous officers take it upon themselves to decide what’s safe.”

Thanks to Jasmine Jackson (law clerk to Marie Dyhrberg QC) and Rachel Simpson (EJP student) for assisting the ADLS Criminal Law committee with its research

This article originally appeared in LawNews (ADLS) and is here with permission.

14 Comments

"...the legislation reflects international laws which New Zealand and the vast majority of the rest of the world have accepted." that statement should be challenged without more evidence that includes for eg Eastern Europe, Russia, Asia, India, Africa, South America...; Penelope Mathew appears to think "the rest of the world" consists only of her Western European academic colleagues & their captured politicians.

"" stirring up hatred on the grounds of religion"" - that would include simply quoting the original religious texts. 200 years ago Tom Paine did it with quotes from the bible in his 'The Age of Reason'; fortunately they had free speech in the newly independent USA so he was quietly ignored. Passing a law that made displaying religious texts to deserved ridicule would have had him prosecuted in court and leading theologians put on the spot defending obscure texts.

Theologians wouldn't have to defend religious texts under hate speech prosecution hearings. The issue under consideration would be the alleged extent of harmfulness of statements made in relation to those texts. Not the validity, or otherwise, of the propositions contained in such texts.

You are right, they would wriggle out of it as ever when religion is questioned. The alleged 'extent of harmfulness' is covered by existing legislation. So shouting 'Fire' is likely to cause harm in a crowded theatre. Similarly putting swastikas on Jewish graves is causing harm whereas publishing arguments that the Nazis didn't kill Jews does not cause harm just ridicule from those who are well informed.

I last read the age of reason 50 years ago - I remember Tom Paine objecting to passages in the old testament where the Israelites won a battle, took slaves and gave some of those slaves to God. These days the issue is a couple of references to killing homosexuals.

Shouting fire in a crowded theater is currently probably legal here and certainly its legal in the USA as the courts eventually said it is in fact legal. It is not about causing harm, it is about intending to incite others to cause harm. It is currently legal to say some pretty hateful things about a protected group, so long as you are not intending to incite others to hate, but under this law change, that may be considered 'normalizing hate'.

Putting Nazi symbols on graves also probably isnt a hate crime, but rather vandalization of property, hateful though it may be, it is not explicitly inciting others to hate, but may be considered 'normalization of hate' under new proposed laws.

There are two other laws you should be across: the summary offences act and the harmful digital communications act which both in some ways address hate speech.

Would also challenge your suggestion the great Thomas Paine was 'quietly ignored'. His work was highly influential in generating the American independence movement and although his fiery polemical style saw him eventually marginalised his key works were immensely popular and formative.

I consider him great too. In the USA he is remembered for being the main instigator of American independence but his atheism made him non-platformed. When he died 1809 only a dozen people came to his funeral. Just try and find a copy of The age of Reason in a public library. Even Auckland.

Deist rather than atheist. His unpopularity at time of death not only due to his excoriating attacks on organised religion, christian doctrines but also against the by now saint like figure of Washington.

'an obvious problem: those words ‘hate’ and ‘hatred’. Politicians toss these words around as if they have some agreed, settled meaning, but they don’t'.

You need to talk to the right politicians Mr DuFresne. Our Jacinda has figured it all out. It's really not complicated - 'we all know hate speech when we hear it' she brightly insists.

I am really pleased some high profile legal people are questioning this law. It feels like travelling back to the dark ages where no one can question basic fundamental going on's. It should be a basic right to criticize any ideology and thereby bring to the fore any anti social behaviour.

“These laws were not inspired by cancel culture but by the very real and ghastly experience of the Holocaust, when human beings were murdered on the basis of characteristics that they could not and/or should not have had to change and Nazi propaganda fuelled these crimes."

Is a Dean of Law really not aware that the Weimar Republic had strict laws against insulting religious groups and that Goebbels was sentenced to jail twice on such charges. Julius Streicher, the editor of the Nazi newspaper Der Sturmer, was sentenced to jail as were other editors.

The court cases were used by the Nazis as a platform to spread their bile further than they might otherwise have been able to.

The attempts at suppressing the Nazis' voice only turned them into martyrs.

Where is the evidence that hate-speech laws have ever stopped the rise of such political movements?

These proposed law changes are clearly in response to the monstrous Christchurch mosque killings. But nobody has ever suggested that if they had been in place the attack would have been prevented. It just seems rather like a smokescreen hiding the sad fact that the law that would have helped was the control of firearms. This had been languishing in parliament for years and then hurriedly enacted after the event.

They're not actually in response to ChCh. Ardern says they are to mislead us but is well aware the proposed changes were part of the party's previous election campaign policy, well before the massacre.

Graham. The CCP through its control of dissenting voices it deems as hate speech is proving very successful at stopping the rise of political and religious movements. Such as democracy. Falun Gong and other philosophic groups also seem well suppressed. The technology enabled ability to control thought is today light years removed from the crude apparatus the Weimar republic had available to it in the 1920/30's.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.