By Sheryl Sutherland*

As you know, the three main asset classes are stocks/equities, fixed income and cash (or cash equivalents. Outside those, in the context of portfolio diversification, people can consider options of gold/metals, EFTS and crypto to be in their own classes too. I won’t be mentioning these, as I consider them to be too high risk for most investors; although gold has had a magnificent run thanks to China – another story.

Supposedly, these different asset classes behave differently during different market environments. The relationship between two asset classes is called asset correlation. For example, shares and bonds are held alongside one another because they are usually negatively correlated, meaning when stocks go down, bonds tend to go up, and vice versa.

However, that theory has been blown out of the water of late. It has been widely accepted that choosing an asset allocation is more important over the long term than the specific selection of securities. That is, choosing what percentage of your portfolio should be in shares and what percentage should be in bonds is important - and impactful. Theory being that uncorrelation between assets offers a diversification benefit that helps lower overall portfolio volatility and risk.

This concept is widely used for those with a low tolerance for risk and/or for those nearing, at, or in retirement.

Your advisor will suggest that you think of asset allocation as the big-picture framework or foundation upon which your portfolio re moving on to the minutiae of selecting specific securities to invest in. We know that we can't consistently time the market or pick individual shares with success. Moreover, they say that staying disciplined with this framework on your investing journey will allow you to more easily reach your financial objectives and will improve the reliability of the expected outcome.

Most people I’ve talked to aren’t familiar with the term ‘asset allocation’, but it is simply a ratio of different asset classes held.

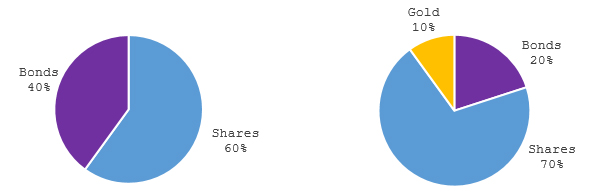

Asset allocation is usually colloquially written about and stated as a ratio of shares to fixed income, e.g. 60/40, meaning 60% shares and 40% bonds. Continuing the example, since bonds tend to be less risky than stocks, the first investor with a short time horizon may have an asset allocation of 10/90 shares/bonds while the second investor may have a much more aggressive allocation of 90/10.

We can extend that description to other assets like gold, for example, written as 70/20/10 shares/bonds/gold, meaning 70% shares, 20% bonds, and 10% gold. These pie graphs give the picture:

Because of the historical negative correlation between stocks and bonds, and because planners want the security of a ‘safe harbour’ when markets go down, the 60/40 split has become the ‘gold standard’ of advice. A recent article posted by Morningstar points out:

“The dual bear market for both stocks and bonds in 2022 created the perfect storm for the 60/40 portfolio, which had been a popular asset-allocation strategy for the past couple of decades. With broad stock market benchmarks down 19% for the year and bonds down 13%, a 60/40 mix of the two suffered its worst performance since the global financial crisis in 2008.

This disappointing showing was followed by a chorus of pundits heralding the death of the 60/40 portfolio as a viable investment strategy. That didn't happen. In fact, a standard balanced portfolio combining a 60% weighting in the Morningstar US Market Index and a 40% weighting in the Morningstar US Core Bond Index chalked up returns of 18% in 2023.”

After some beautiful graphs, they conclude that there are lessons to be learned in the 60/40 portfolios, fall and redemption for one. It’s not realistic to expect any portfolio strategy to excel in every market environment. Now this is what really interested me, it’s a fairly limp summation.

With the assistance of a summary by Brent Wheeler (admittedly a quant but he can be forgiven, he thinks outside the box) the challenges of the traditional 60/40 split are as follows:

1. High Equity Valuations:

The stock market has experienced significant growth, leading to high valuations. This increases the risk of lower future returns

2. Monetary Policies:

Unprecedented monetary policies. such as low interest rates and quantitative easing, have impacted bond yields and returns

3. Inflation and Interest Rates:

Rising inflation and interest rates have reduced the effectiveness of bonds as a hedge against equity risk

4. Geopolitical Tensions:

Events like the war in Ukraine and tensions between major economies have added uncertainty and volatility to the markets

5. Correlation Between Stocks and Bonds:

The historical negative correlation between stocks and bonds has weakened, reducing the diversification benefits of the 60/40 split

6. Exclusion of Alternative Assets:

The traditional 60/40 portfolio often excludes assets like Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), gold. and commodities. which can provide additional diversification and protection against inflation

Despite these challenges, some experts argue that the 60/40 portfolio is not dead and can still provide balanced returns with proper adjustments and diversification.

The question I have however, is why use bonds at all? If your portfolio is structured for long term investment the risk of equities diminishes at around five years. At that point, the returns on a 5% bond are the same as an equity of 7.5%.

Consider this:

- Equities return somewhere between 6-8% on average.

- Bad years don’t happen that often.

- Even ‘quite bad’ still has you in the money.

Remember Warren Buffett and his portfolio – 90% equities, 10% cash. You can’t argue with the returns he has achieved for his shareholders.

*Sheryl Sutherland is director of The Financial Strategies Group, and author of Girls Just Want to Have Fund$ – Every Women’s Guide to Financial Independence, Money, Money, Money Ain’t it Funny – How to Wire your Brain for Wealth, and co-author of Smart Money – How to structure your New Zealand business or investments and pay less tax. You can contact her here.

5 Comments

Good article - it’s being honest with yourself around the investment timeframe. If it’s truly 5+ years I would be in the WB camp……

I agree with much of what you say. Some comments however:

1. TiPs are just a subset of fixed income/bonds. A properly structured portfolio would have a 50/50 allocation to nominal and inflation linked bonds within the overall allocation to bonds. i.e. a 100% weight to nominal bonds means that the investor is taking a bet that actual inflation will always be lower than expected (market priced) inflation whereas a 50/50 allocation (duration adjusted) is an agnostic view.

2. Cash and government issued fixed income are really one and the same, its just a question of how much duration you hold overall i.e. cash is also a subset of fixed income. Given fixed income was so objectively expensive, the 60/40 portfolio would have been valid in 2022 had the allocation to Fixed Income been actively managed with a lower duration via much greater cash holdings relative to bonds. This requires active management.

3. Prolonged equity underperformance can happen. It took decades for the US stock market to recover from the 1929 crash and similarly for Japan post 1989. It would be a brave person to claim that this cannot happen again. So whilst on average, statistically, a long term view of holding equities makes sense, the outcomes for each investor are very path dependent. You can't ignore that the downside risk of such an event would be catastrophic for the individual.

4. A person near retirement cannot take risk of the equity market collapsing. i.e. investment horizon still matters, critically. But this also means taking less duration risk too i.e. retirees with cash redemption expectations are also exposed to bond markets underperforming.

Just on US bonds,

Strategists at Bank of America Corp. recently got their hands on US bond market data going all the way back to the founding of the nation. And it shows, they say, that never before has there been an extended period of losses like the past three years.

It’s hard to know, of course, just how accurate the figures were from those early post-colonial years. (How often could bonds have traded during the War of 1812?) Still, there’s something jarring about a worst-in-236-years statistic. It’s a poignant reminder of the magnitude of the pain rippling through the financial world in the aftermath of an inflation shock and interest-rate surge that few saw coming. The pain was severe enough to take down Silicon Valley Bank and three other regional lenders this year and pushed others into crisis until policymakers in Washington rushed to prop them up.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-08/bond-market-pain-is-…

Kiwis have to take into account the tax consequences of tax free dividends by NZ companies paying full tax on their earnings, the tax effect of owing shares of foreign companies (except Australia), the tax on the interest payments of bonds and other interest beating notes.

I am old (playing the market for over 50 years) and my experience tells me to avoid bonds and buy 70% dividend paying companies (especially ones paying full tax on their earnings) and 30% smaller listed NZX companies with growth opportunities.

It has served me well. I pick them all myself. I find this easy in a country like NZ with not too many companies to follow. Also I don't pay fees to so called professionals and use a discount broker.

Cheers,

Terry

The last thing I'd sink my money into would be gold.

It's costly to store, dangerous to store at home, you'll need insurance, has no dividend or return, there's premiums and transaction costs, and illiquid. Long term, the returns have been poor.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.