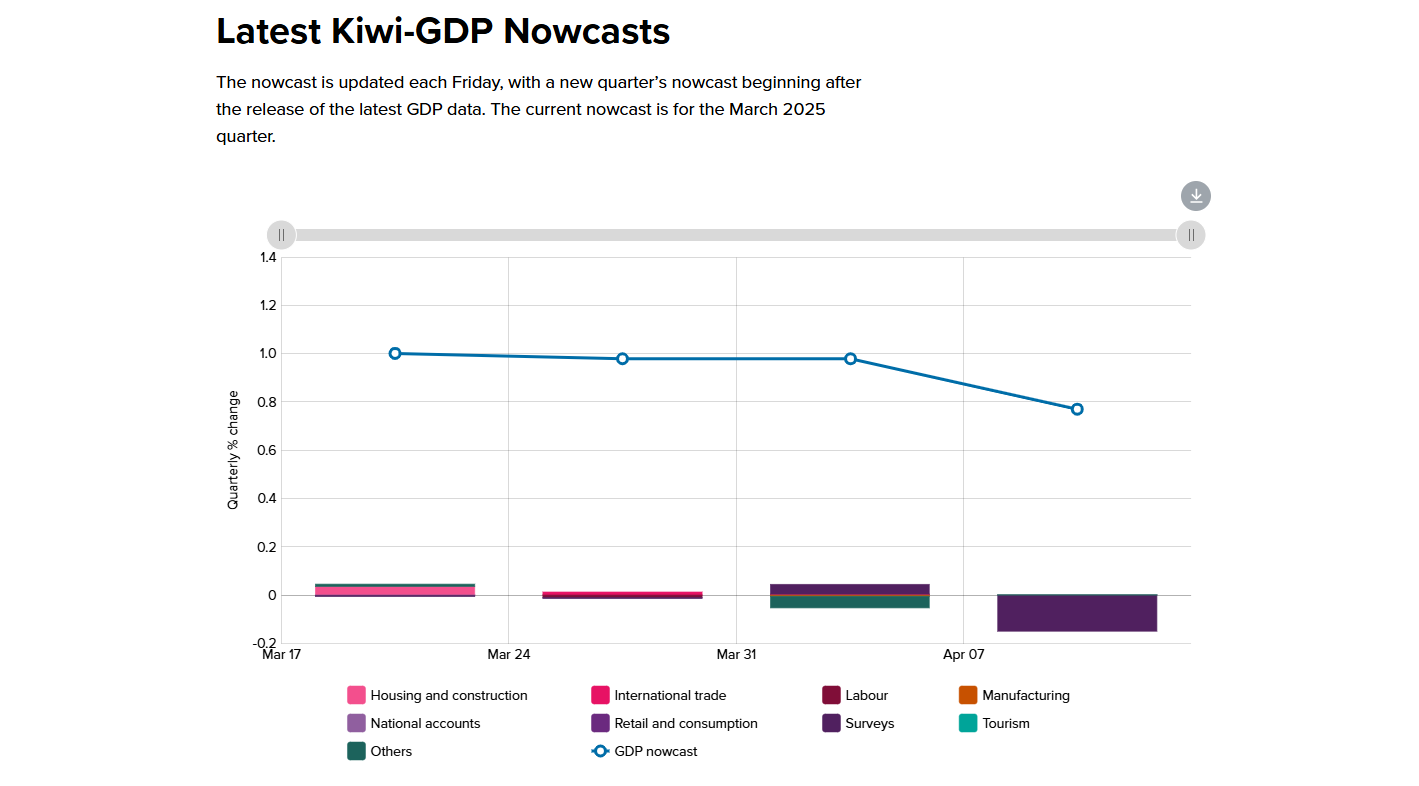

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has launched a ‘nowcasting’ model, which will give a live estimate of gross domestic product in each quarter based on frequently updated data releases.

It is based on the New York Fed Staff Nowcast and aims to make up for the long lag time between official GDP data collection and publication. Stats NZ releases the official numbers more than two months after the quarter ends, making it only useful for historical analysis.

The Reserve Bank already relies on forecasts, economic surveys, and high frequency indicators to make its monetary policy decisions. But this work has been expanded into a public ‘nowcast’, called Kiwi-GDP, which will be updated each Friday.

It is similar to Massey University’s GDPLive which uses daily data updates and machine learning to estimate economic activity. However, the RBNZ’s model primarily relies on monthly data releases.

Currently, the two models offer vastly different assessments of GDP for the March quarter: GDP Live predicts a flat quarter at 0.2%, while the RBNZ forecasts a 0.8% bounce.

In speech this week, RBNZ Chief Economist Paul Conway explained that nowcasting is used to assess economic conditions in the “very near term,” serving as a starting point for longer-term forecasts that rely more on “structural relationships in the economy and how economic events are likely to play out.”

An analytical note released alongside the new tool said Kiwi-GDP’s accuracy was comparable to the Reserve Bank’s official projections, despite the latter being finalised a month earlier.

This was evident when backtesting the nowcast during the COVID era, when unusual data signals confused the model. Expert forecasters were better able to interpret the noisy data and did a better job at predicting growth.

Kiwi-GDP uses 36 data inputs, mostly monthly stats, to measure economic activity. These include: the ANZ Truckometer survey, electricity generation, housing sales, bank card transactions, tourist arrivals, farm production numbers, and monthly filled jobs.

It is updated each Friday at 3pm with whatever monthly data has been collected that week, meaning it should become more accurate as the quarter progresses.

Conway emphasised that this was not a new capability for the bank, which has been calculating real-time estimates of GDP for many years.

“It's not a huge change in terms of the technology we use, we're just sort of putting a bit of it out there in the interests of transparency,” he said.

Cranky critics

Much of his speech focused on correcting perceived inaccuracies about the Reserve Bank’s ability to forecast the Official Cash Rate (OCR) and economic conditions.

He argued that some media columnists had written “misinformation” about the central bank’s forecasting, and he wanted to set the record straight.

“There's been a few op-eds that I just look at and go, Oh my goodness, that is just digital dust. It’s click bait, and it's in mainstream media, which is all the weirder,” he said.

The bank was always willing to learn from criticism, but some things had been written that were “so full of holes” there was nothing to talk about. “It has to be serious,” he said.

Conway wouldn’t name any specific columns or journalists, but one likely example is ACT Party co-founder Richard Prebble, who has repeatedly derided the central bank for not using GDPLive.

In June last year, he compared the RBNZ to a French general in World War II who refused to use a telephone to coordinate his troops, and therefore lost a battle before knowing it had begun.

This was not correct on either count—the story about the general lacks evidence, and the RBNZ was using a nowcast at the time—but he doubled down in another column earlier this year, claiming the central bank made policy errors due to “faulty data”.

While the Reserve Bank did acknowledge that incorrect data releases from Stats NZ last year created confusion for its monetary policy assessments, Massey’s GDPLive weren’t accurate either. It picked flat growth in the last two quarters of 2024, whereas revised official figures now show a 2% plunge.

GDPLive also estimates inflation but not with any great accuracy. It is a useful tool to get a general sense of the direction of travel but has not yet proved itself to be a precise tool.

OCR track isn’t gospel

Conway also used the speech to point out the bank's Official Cash Rate projection, which it publishes every three months, is conditional on all other elements of economic forecast.

RBNZ policymakers have often said the media and the market pay too much attention to the OCR track and treat it like a commitment to future policy decisions.

“This is our best estimate of how the OCR will need to change over the forecast period to meet our inflation objective, conditional on the economic outlook,” Conway said.

“That last bit – conditional on the economic outlook – should be read as being bolded, highlighted, and jumping off the page like a neon sign. I cannot overstate the importance of this conditionality. If the economic outlook changes, which it almost always does to some degree, then our projection for the OCR will also change”.

Because the rate track is conditional on everything else in the economy, it should almost never be interpreted as a signal of what will happen at future meetings, he said.

The OCR track is always set to return inflation to 2% over the medium term in the bank’s mathematical models. This means the track is more a mechanical outcome of the economic forecasts than a strategic plan by the Monetary Policy Committee.

“Broadly speaking, it is changes in our outlook for the OCR that tell you whether underlying inflationary pressure in the economy has changed,” Conway said.

Changes in inflationary pressure may not show up in the inflation forecast, but can instead be reflected in the OCR track. A higher path indicates stronger underlying pressure, and vice versa.

Worst-case tariff scenario

Conway said the bank would consider publishing multiple economic scenarios and policy responses, as suggested by Ben Bernanke at the recent conference.

“In the past, the Reserve Bank has published alternative scenarios, not for some time. I think when I first worked here in the late 90s, we were doing that fairly regularly,” he said.

“I'm very open to it. We'll have a think about it. Maybe this global trade war is an opportunity for us to publish a scenario on a worst case scenario. That’s not a promise, it's something we’ll think about between now and [the next policy meeting]”.

The chief economist said it was “hard to get a handle” on how new trade barriers would affect the local economy and inflation. The forecasting team was using a new tool called G-Cubed to estimate outcomes, but it was hard to know what tariff settings to model in the first place.

“I think what President Trump sort of put out before the partial pause, hopefully, is a worst case scenario. So we could model a worst case scenario and then compare it to the current scenario — that gives us an idea of the impact,” he said.

8 Comments

Currently, the two models offer vastly different assessments of GDP for the March quarter: GDP Live predicts a flat quarter at 0.2%, while the RBNZ forecasts a 0.8% bounce.

There is no 'true value' and GDP reads are subject to estimation errors. Understanding the strengths and limitations of your data collection is crucial.

“It's not a huge change in terms of the technology we use, we're just sort of putting a bit of it out there in the interests of transparency,”

As should be standard and your duty Mr Conway. We pay your salary.

Agreed, but your last stayement is a bit negative, his predecessor didn't provide it.

If we can't pick holes in things, what's the point of living?

I'd prefer to focus on the positive.

About time. The technology to do it has been around for years.

Clearly had to wait for Orr to finish in order to get this improvement through

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.