Since the US presidential election last year, I have been commenting regularly on various aspects of Donald Trump’s agenda and what it might mean for America, financial markets, and the rest of the world. There has been no shortage of chaos, but that was largely expected, given the president’s ham-handed, erratic “method” of policymaking.

As I noted in February, and again in March, other economies may respond to Trump’s aggression by boosting their own domestic demand and reducing their dependency on US consumers and financial markets. If there is a positive spin to the current mess, it is that Europeans and the Chinese have already started to pursue such changes. Germany is loosening its “debt brake” and allowing for sorely needed investment, and China is said to be studying its options for stimulating domestic consumption.

For any country that depends on international trade and markets, it is abundantly obvious that, even if the United States can be persuaded to rein in its trade-war policies, new trading arrangements will be necessary. Many are already seeking ways to increase trade among themselves and to forge new agreements to lower non-tariff barriers in the rapidly growing services trade.

As a bloc, the rest of the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom) is nearly as large as the US. Add the other participants in UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s “coalition of the willing,” and America’s erstwhile allies could offset much of the damage that Trump has inflicted. By the same token, if China could refashion its Belt and Road Initiative in close coordination with India and other larger emerging economies, that might prove transformational.

Such moves would mitigate the effects of US tariff policies and threats. But they will not be easy to pull off; if they were, they already would have happened. Today’s trading and financial arrangements reflect a variety of political, cultural, and historical factors, and the Trump administration will try to derail any changes to the status quo that could benefit China.

What matters, then, is precisely how other large economies go about stimulating domestic demand, mobilising investment, and forging new trade ties. At a recent conference on “globalisation and geo-economic fragmentation,” hosted by the think tank Bruegel and the Dutch central bank, I was reminded just how skewed global GDP growth has been since the turn of the century. A simple analysis of annual nominal GDP figures from 2000 to 2024 shows that the US, China, the eurozone, and India collectively contributed nearly 70% of all growth, with the US and China accounting for almost 50% between them.

This finding further underscores the fact that US tariff threats must be met with higher domestic demand elsewhere. But here is a reality check: The only other country that could singlehandedly boost its demand and imports by enough to compensate for America’s declining share of the global economy is China.

But what if China isn’t operating singlehandedly? As we have seen, Europeans are already taking steps to increase investment and defense spending in ways that will benefit both the EU economy and others, like the UK. And, of course, India’s economy has been growing faster than many others in recent years, suggesting that it could have some scope to pursue more domestic stimulus. What if all these other economies were coordinating their own policies?

Such coordination probably might not have the same global impact as the 2009 London G20 agreement, which introduced wide-ranging global reforms and new institutions to address the causes of the global financial crisis and its fallout. But if these countries signaled to the rest of the world that they were engaged in some kind of consultation to harmonise their economic policies and advance shared objectives, that could have quite a positive impact.

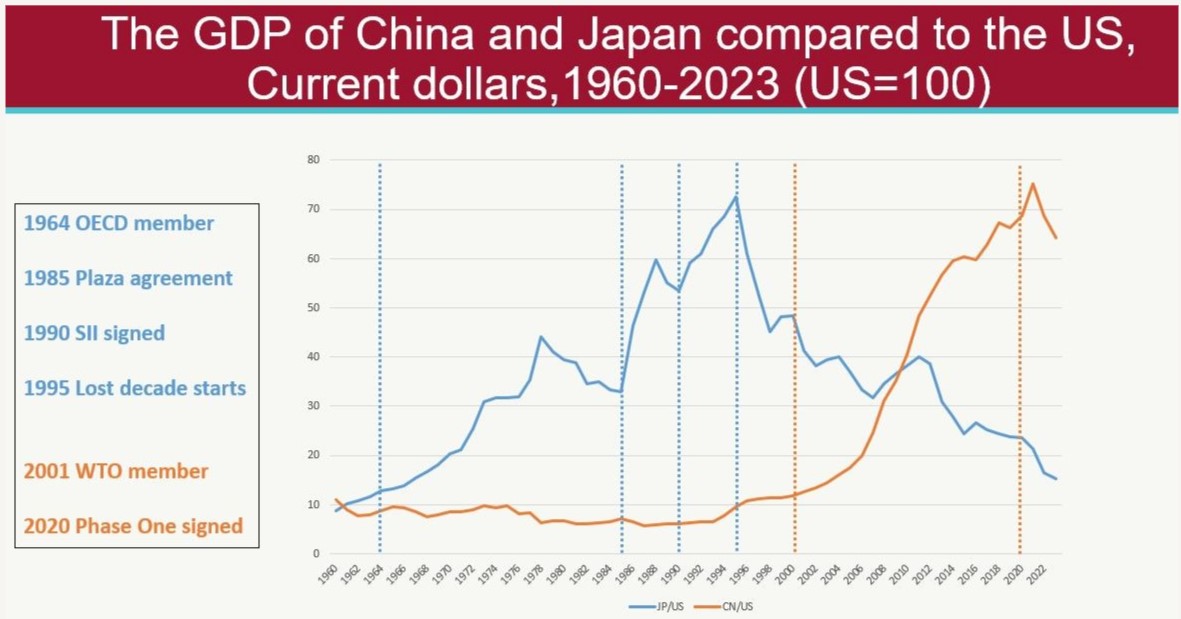

Finally, something else from the Bruegel conference has been nagging away at me. It was a chart (see below), presented by Bruegel Senior Fellow André Sapir, highlighting the similarities between Japan’s rise, when its GDP grew to around 70% that of the US in the 1990s, and China’s today. Then as now, the great fear in America was that it would be “surpassed.” But what does America really want? Does it want to be able to say that it is the largest economy in nominal terms, or does it want to provide wealth and prosperity for its citizens?

These are not necessarily the same thing. What the current US administration fails to understand is that other countries’ growth and development can make Americans themselves even wealthier. Perhaps, someday, Americans will elect leaders who can comprehend this basic economic insight. For now, though, they seem destined for many years of turmoil and persistent uncertainty.

Jim O’Neill, is a former chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management and a former UK treasury minister. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025, published here with permission.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.