Something strange is happening in Australia. The federal government is promoting legislation to reduce one of the country’s largest exports – education services.

Last month, the government announced that it will limit the number of new international students that can commence their Australian studies in 2025 to 270,000. This will bring the number of students in the university and ‘vocational education & training’ (VET) sectors back down to pre-pandemic levels.

International education has been a tremendous success story for Australia. According to the Department of Education, it was worth $36.4 billion to the Australian economy in the 2023 financial year, making it the fourth highest source of export revenues.

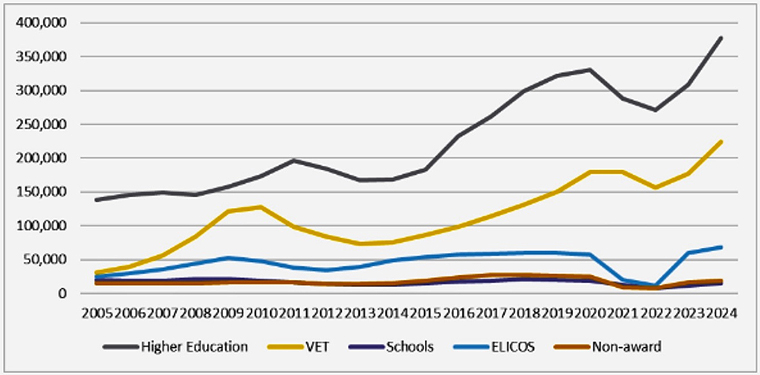

And as the graph below demonstrates, it’s a growth industry.

Year-to-date international student enrolments by sector as at March, 2005-2024

Source: Parliament of Australia

(ELICOS stands for English language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students)

This success is attributable to a range of factors. Two key ones are the use of the English language in Australia and the country’s proximity to the large Asian markets driving much of the demand for international tertiary education services, particularly China and India.

The quality of many Australian universities has also played a part. In the latest Times Higher Education rankings, six Australian unis placed in the top 100. Unsurprisingly, five of these had the highest number of overseas students among Australian universities in 2022 (the most recent available data).

In each case that was more than 10,000 students – Monash University (19,290), the University of Melbourne (17,316), the University of Sydney (16,912), the University of Queensland (16,376), and the University of New South Wales (UNSW) (11,599). These figures represented a significant proportion of each university’s total enrolments – 30% in the case of the University of Queensland.

Over the last fifteen years, the fees from foreign students have become a major source of revenue for many of Australia’s tertiary institutions, and the top ranked ones in particular. This has been reinforced by the higher fees usually paid by foreign students.

Domestic students have benefitted from this situation financially as their attendance has effectively been subsidised by the presence of foreign students. Of course, the Australian government has also been a winner in this situation.

There’s been another benefit from the influx of international students. Many highly skilled and ambitious young students have stayed on in Australia and made valuable economic and social contributions.

So why does the government now want to undermine such a national success story?

According to the ministers who announced the student cap last month, it will ‘ensure a managed international education system designed to grow sustainably over time’. The key is the word ‘sustainably’. And that’s where the politics comes in.

The headlines in Australia at the moment are dominated by Gaza/Israel/Lebanon. But the two issues that exercise the minds of a much larger number of Australians are housing and the cost of living. And with an election expected by May next year, the Labor government recognises the urgent need to be seen to be doing something to address those issues.

Immigration, both permanent and temporary, is perceived by many Australians as contributing to the housing shortage and to the excess demand in the economy driving inflation. The government has struggled to control immigration since its election in 2022, partly thanks to a strong jobs market with unemployment remaining low at 4.1%. The final immigration figure for 2024 is likely to be much greater than the target the government set itself.

The hundreds of thousands of international students who have flooded into the country post-Covid are seen as part of the immigration ‘problem’.

Certainly, anyone looking for rental accommodation in central Sydney and Melbourne can attest to the adverse impact of high student numbers on the housing market.

The government hopes that voters will view the cap on foreign students as an effective mechanism to ease the housing crisis and take some of the heat out of inflation. It probably doesn’t hurt that foreign students can’t vote.

Needless to say, the student cap proposal has many opponents.

The Business Council of Australia argues that the cap will ‘damage the economy and deliver long-lasting harm to Australia’s fourth largest export sector’. According to the BCA, that sector contributed almost a quarter of GDP growth in the March 2024 quarter and ‘it seems entirely counterproductive to stymie that growth when we face economic headwinds’.

This is a view expressed by many in the business sector. However, others claim that businesses like foreign students because many of them work in part-time, often poorly paid jobs that are otherwise difficult to fill.

Many of the universities are of course furious that restrictions are being placed on their intakes. Some are saying that it will damage the sector’s reputation overseas and that the resulting loss of fee revenue will trigger major cost cutting at home. The Australian National University, ranked 73rd in the world, says it will need to cut millions of dollars from its 2025 budget.

Interestingly, in the minutes of its latest board meeting, the Reserve Bank of Australia suggested that it’s unclear whether the student cap would in fact assist in the fight against inflation. The cap ‘would be likely to reduce aggregate demand (including for housing), but also lower growth in population and therefore the economy’s supply capacity’.

The legislation for the new system – the Education Services for Overseas Students Amendment (Quality and Integrity) Bill 2024 – is not yet law and the government may struggle to get it through the Senate.

Time is running out if the system is to commence in 2025. Universities have been informed of their individual student caps but it’s difficult to plan without certainty.

Australia needs to be careful. International education in English is a competitive business in the Asia-Pacific region. Rejecting foreign students could undermine Australia’s reputation as a welcoming and pleasant place to study.

And that could create opportunities for competitor countries, like New Zealand.

*Ross Stitt is a freelance writer with a PhD in political science. He is a New Zealander based in Sydney. His articles are part of our 'Understanding Australia' series.

28 Comments

We had a golden opportunity during COVID to capture the International student market, f**ked it up, and now our universities are shedding courses and staff. I have zero confidence our powers that be will do any better when presented with a new opportunity.

I have 100 % confidence that VC Robbo will add another zero to Otago University's current $ 200 million debt , and bankrupt a previously fine academic institution ...

... thankfully , it's only a Uni going down the gurgler ... ... had Labour won the 2023 election he was on course to bankrupt the entire nation ...

The 2021 special residence visa was a free giveaway for nothing.

Could have run special student-to-residence visa. It would have attracted international students to stay and spend in NZ by giving them opportunities to receive residency upon completion of the selected course.

The cap is practically meaningless lip service since 270,000 is slightly more than 1% of the Australian population.

It's still more than a 40% reduction. At these numbers, that is a lot of accommodation held by students over locals - and parts of Aus have a very low rental availability.

How many international students are prepared to pay $150k to do "Maori Studies"? NZ Universities are killing their golden goose, and when they go broke, they will only have themselves to blame. Either teach globally relevant degrees or get out of the international education market.

I think ACT sums it up with a TUI ad.

https://www.reddit.com/media?url=https%3A%2F%2Fpreview.redd.it%2Fis-thi…

Of course, NZ will still be attractive to the fake students who only enrol in something in order to get a visa, so they can work 60 hours a week instead of attending classes, and then apply for permanent residency at the end of their studies. Those are the "students" that Australia is trying to get rid of.

NZ will still be attractive to the fake students

That's the low hanging fruit that our universities target anyways. International students serious about academics and career growth have far better options in North America and Europe.

Anyone has to be either stupid or arrogant to call our tertiary education in its cuurent "world class".

NZ isn’t a real player in this space and never will be. US-UK is where 90%+ of the top “international” students target, then a sprinkling to other Europe, Canada, Aus, and a few top Asian universities. We can only attract riff-raff dregs (academically/wealth wise).

Shane Legg ! ... we don't need to attract any academic riff raff dregs when we can produce amazing world leading tech entrepreneurs from within ... ... it's just , we're too damn thick to support & hang onto them ...

Agree. Our universities are going down hill fast, led by Auckland and their irrelevant Māori nonsense course. This sort of crap is not relevant to NZ students studying anything important, and is just a joke as far as international students are concerned. Very disappointing that this sort of thing is even allowed. It is the height of wokeness, and will one day be cancelled…but of course the university will be broke first.

Having worked in both the Australian and New Zealand university systems, I am cautious in regard to the relative international competitiveness of the education sectors in the two countries. As a starting point, the top Australian universities have much higher international rankings. But that is just the starting point. If NZ is to further expand its international education focus than that needs to occur within a framework of an industry that seeks long-term sustainability. A focus on maximising short-term returns (boom and bust) is not the way forward.

KeithW

Very well put

I did my masters at ANU 14 years ago and it was 20th ranked globally. Now 73rd. I think the ranking system or coverage must’ve changed to some degree. What I did notice at ANU was that they bent over backwards to help foreign students pass no matter what, even when they really weren’t up to scratch. It was already a big gravy train then and no doubt more so these days.

Two things happened. One is that the Chinese Universities got a lot better, and moved up the rankings, with 7 institutions now in the Top 100. The other is that the western Universities that sold education as an "export" (NZ, Australia, Canada) lowered their academic standards and rigour in order to get as many international students as possible. The losers are the domestic students who now get a substandard educational experience and a less reputable degree qualification, all whilst still paying top dollar and bearing the burden of a lifetime of student loan repayments.

Why not call it what it is?

Selling Visas for the price of tuition.

A few more Auckland bus bashings and we wont be able to even sell visas.

Unfortunately, the bulk of migrants face much worse living conditions back in their home countries.

That's usually why many of them put up with crap such as workplace exploitation, low pay, miserable working conditions, expensive housing and so on.

I liked it better when Auckland strived to be like Copenhagen and Helsinki. Now we're content in not being as bad as Delhi.

That's usually why many of them put up with crap such as workplace exploitation, low pay, miserable working conditions, expensive housing and so on.

How did we create this NZ utopia?

"The truth is that international education is a people-importing industry, not a true export industry.

The ABS export estimates are false because they include all expenses incurred by foreign students in Australia as exports, even if the money was earned while working in Australia.

Most student visa holders come from low-income countries and start working in Australia right away to fund their living and tuition expenses.

Australia’s best journalist, Frank Chung, debunked the international education export “scam” once and for all in investigative report published on Monday at News.com.au."

https://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2024/05/the-mask-comes-off-internation…

Oliver Hartwich at NZ Initiative argues that it is much easier for both sides of the political spectrum to let universities be in the business of selling degrees and visas to foreign students than the alternative, which is to fund them properly.

Easier how and for whom?

It seemed easy enough to fund them back in the 90's when I completed my degree. There was also a clear career path to follow.

Where did it go wrong?

Universities became property investors? They became mere sellers of shiny certificates and degrees rather than higher educators? The debt model?

Or maybe it's the story being sold that is false.

A rate-free property investment company with a University attached to suck in the punters and their cash?

The education export is a rort in both Aussie and NZ. It's largely feeding off the Global South for false dreams and hopes. And the parasites are making out like bandits,while providing cheap and slave labour for the domestic economies.

I include the grossly overpaid Vice Chancellors among these grifters. Andrew Barkla is one of the worst. Obscene remuneration.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-07/idp-education-ceo-andrew-barkla-…

Yep

I love teaching, but universities these days are a weird mix of arcane rites and passages, stupefying bureaucracy, neoliberal business models, and phoney virtue signalling

but I tolerate those things because I love teaching. Like many lecturers

Australia:

Ross Stitt reports that domestic politics around housing pressures and the cost of living - in the face of an upcoming election - sees Australia moves to limit international student numbers

New Zealand:

We have no such concerns around housing pressures and the cost of living caused by growth in population. We need to let as many private individuals and businesses sell permanent residence as possible.

We have no such concerns around housing pressures

Kiwis who have an issue with the falling living standards and shrinking economic opportunities are free to leave the country as always.

8 universities is too many for a country of 5 million people.

If we can get over the competitive, empire building mindset we now have and create fewer, higher quality institutions who collaborate, we might stand a chance of salvaging the university system.

Given the dominant ideas of zero-sum games, I don't like the chances.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.