By David Skilling*

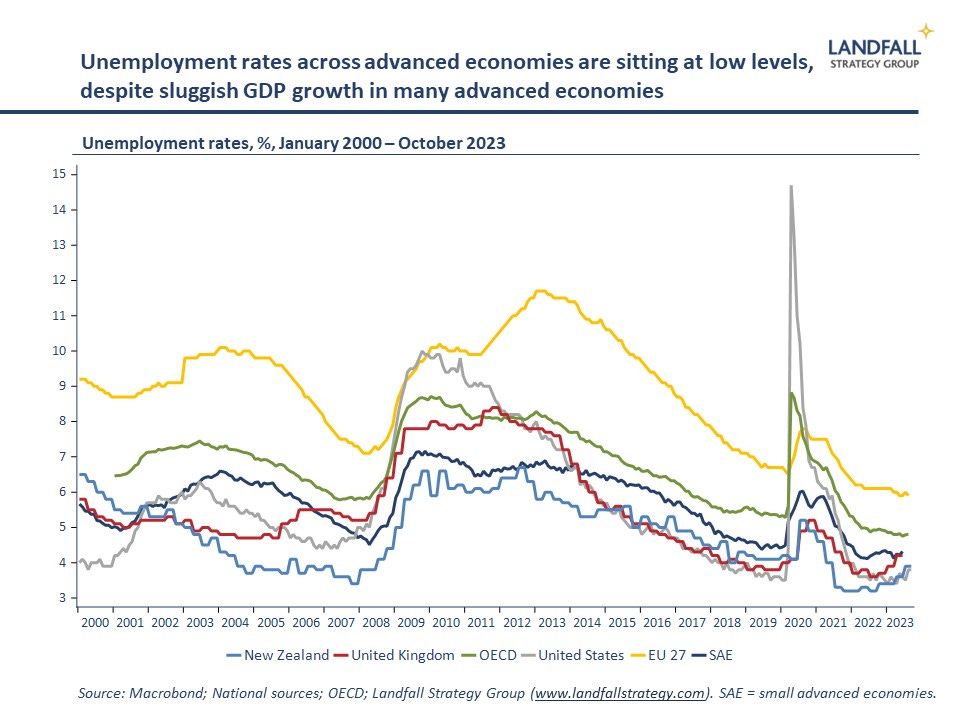

Across advanced economies and beyond, labour markets are tight with unemployment rates at or close to historic lows – 3.8% in the US, 5.9% in the EU (despite the eurozone being on the cusp of recession after this week’s data confirmed a Q3 GDP contraction), and 4.2% in the UK. A similar picture is seen across small advanced economies.

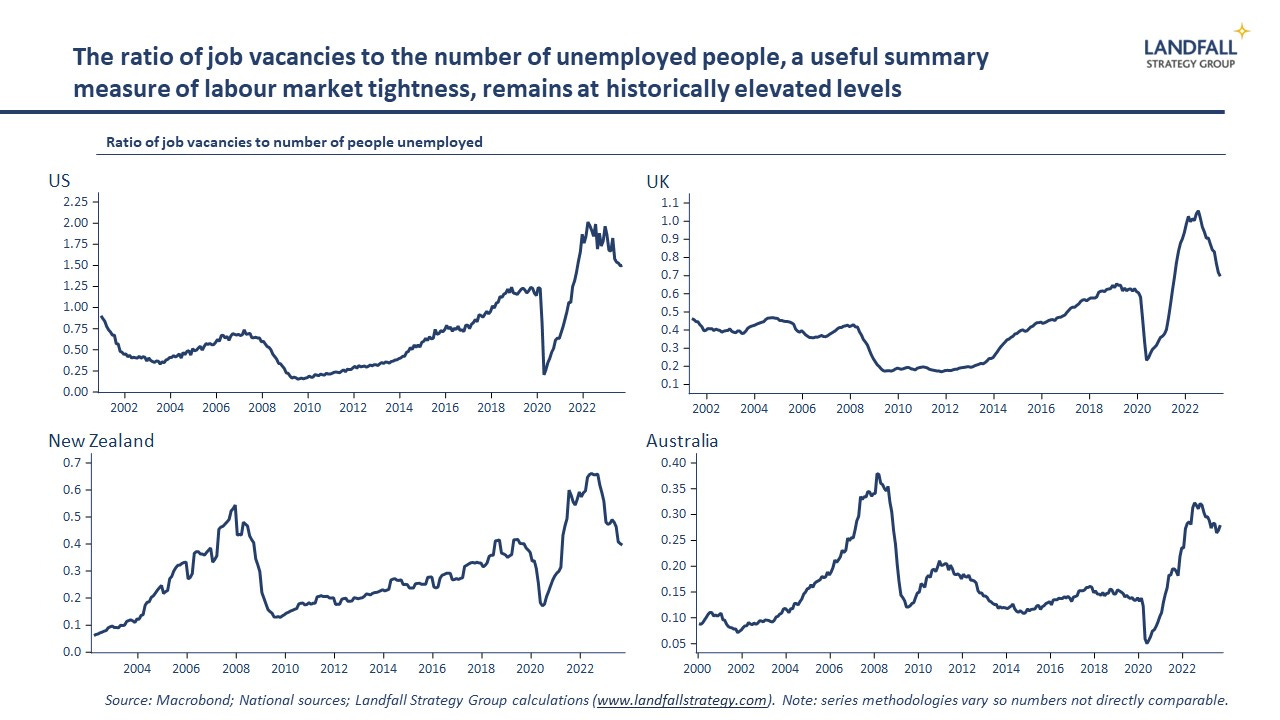

Employment levels have recovered above their pre-pandemic levels in most advanced economies. And job vacancy rates remain at high levels, even if they have come off their record highs. Part of this tightness reflects substantial churn in labour markets through and since the pandemic, as people move between jobs and occupations. Quit rates soared as people looked for better jobs, particularly moving out of sectors such as retail and hospitality.

Relatedly, preferences around labour market engagement have shifted. It is difficult to quantify this, but the pandemic experience reshaped the way that some thought about work; participation rates in some cohorts reduced (e.g. early retirement). And there are generational differences in attitudes to work: from quiet quitting to the lie flat movement in China. It is striking that employment has increased by much more than hours worked over the past few years, implying reduced average hours per employee.

This means that there are constraints on labour availability. Business surveys from the US and the UK to New Zealand commonly report that lack of workers is a major constraint on expansion.

Indeed, there are many examples of labour supply related constraints around strategic projects in the US and Europe. TSMC’s new semiconductor plant in Arizona is being delayed until 2025 because of a shortage of skilled construction workers. There are similar issues in Germany, where the (heavily subsidised) influx of planned semiconductor facilities (TSMC, Intel, and others) are confronting substantial labour shortages amid an aging population. Aspirations around industrial policy in many Western economies are constrained by the absence of workers.

Structural labour market tightness

Some of these developments are short-term in nature, reflecting the major shocks to labour markets through the pandemic. But some of these forces are structural: changed preferences are partly sticky, for example. And many economies are close to the upper bound of labour supply with high employment rates – meaning that labour supply growth will be more challenging to achieve than over the past few decades. There are fewer people available to draw into the labour market.

Looking forward, demographics will be a key constraint on labour supply. Across advanced economies (with the partial exception of the US), populations are aging – with weaker/negative working age population growth. In Europe, for example, the working age population is forecast to contract by ~20% by 2050. There are even more substantial drops in the working age population in multiple East Asian economies that are deeply integrated into the global economy, such as China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The working age population in Japan and South Korea are forecast to decline by 30-40% by 2050.

As discussed in a previous note, this will significantly constrain growth in the global labour supply – reinforcing tightness in labour markets and adding to wage pressure. There are regions of the world with stronger demographics, such as South Asia and Africa. But these economies are not currently deeply integrated into the global economy, and so the impact on global labour markets will be more gradual.

This suggests that labour shortages are likely to be a bigger concern across advanced economies than mass unemployment due to the impact of new technologies such as AI and automation. Of course, policy attention needs to be paid to ensure that people have access to the right skills to participate in the emerging global economy. But in general, labour markets are likely to remain tight.

Implications

Overall, these dynamics mean that bargaining power has shifted towards labour, allowing workers to demand better terms and conditions. This will mean upward pressure on wages, as well as more worker-friendly employment conditions (such as flexible working). This stronger bargaining position for labour is also reflected in the elevated levels of strikes/industrial action in the US, the UK and elsewhere.

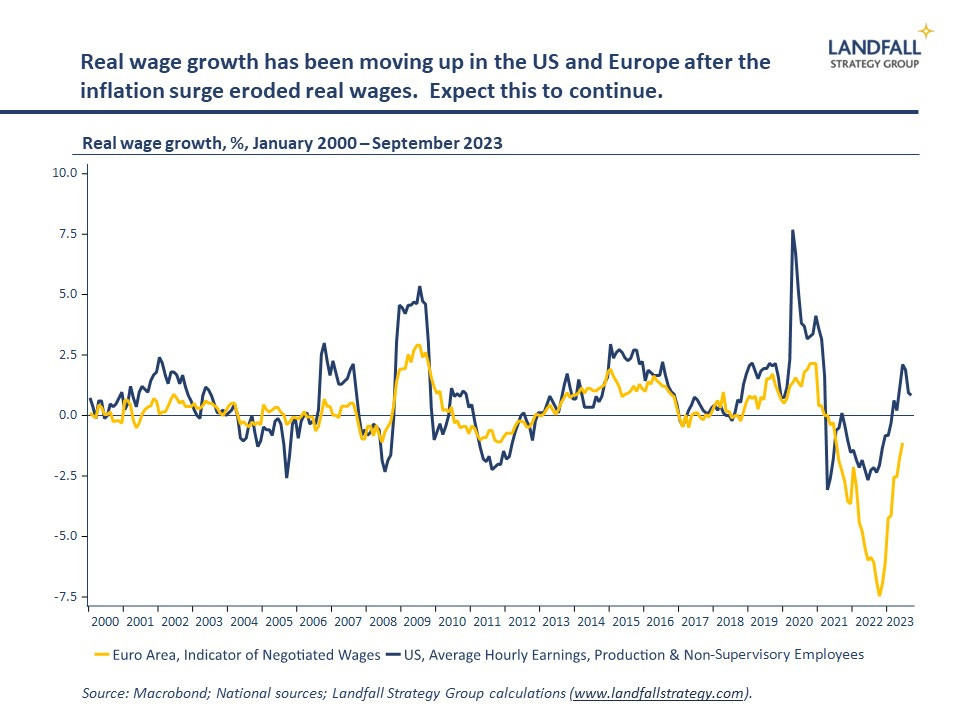

Although the surge in inflation reduced real wage growth, this is turning around and we can expect stronger real wage growth – with nominal wage growth running ahead of inflation. This will likely compress firm margins as well as leading to price pressures across the economy.

Sustained tightness in labour markets is likely to contribute to structurally higher inflation. The deflationary process from the 1990s was supported by a rapid expansion in the global labour supply; this process is now weakening if not reversing, which will put upward pressure on trend inflation. This is one reason why I expect structurally higher levels of inflation over the coming period.

There are a few implications of these labour market pressures. First, expect a stepped-up global war for talent – with labour-constrained economies more aggressively competing for migrants. Indeed, even countries like Poland and Hungary, with strong anti-migrant political lobbies, have been working to attract migrants from India and Pakistan to support the growth of key sectors (for example, the EV battery sector in Hungary).

And recent OECD data reported record migration flows across OECD countries in 2022. Many small economies, from New Zealand and Singapore to the UAE and Ireland, are experiencing very strong migration inflows. Expect economies to set migrant-friendly policies to offset the weakening organic working age population growth. Countries that can offer easy paths to integration (language, residency, etc) are likely to have an advantage.

A second implication is that tight labour markets and increasing labour costs will strengthen incentives for investment in automation, AI, and so on. These technologies can lift labour productivity, as previous notes have discussed. It is not a coincidence that countries with the most rapidly aging populations have the highest densities of industrial automation.

Third, variation in these global labour dynamics is likely to shift the location of economic activity around the world. Although abundant labour supply will not be the source of advantage that it was to the East Asian economies over the past several decades (because of declining labour intensity of manufacturing), there is still some advantage. Global supply chains are likely to be reshaped by access to labour, along with friend-shoring/de-risking dynamics and attempts to make supply chains more resilient.

One of the globalisation dynamics over the past few decades was to allocate production to locations with large labour forces. Current policy efforts to allocate production to economies with already tight labour markets in the name of derisking or resilience will lead to significant pressures. Indeed, industrial policy initiatives which attempt to reshore activity will be constrained by labour supply realities – as noted above. Blocs need to have access to labour as well as capital, technology, commodities.

Overall, tight labour markets will be a defining characteristic of the global economy over the coming decades – with implications from higher inflation to a new global economic geography. Firms, investors, and governments need to position for a labour crunch in many parts of the global economy.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

19 Comments

Good article, especially in terms of the longer term structural issues. Near term, I think the labour market is going to loosen quite a bit and unemployment increase quite a bit. Some of the big employment sectors - retail, hospo, construction - are really starting to struggle, not just in NZ but across much of the world. Luckily, the structural labour force issues will limit the damage in terms of unemployment, as will the flexibility that comes with having many people here on work visas - if the work disappears, they go home rather than joining the dole queue and burdening the government. I think this factor, this benefit if you like, is an under-recognised one in terms of high reliance on immigration (temporary and permanent).

Under Labour most immigrants were brought in on permanent residency visas, or a "pathway to PR". This is one of the big differences between Labour and National - National brought people in on temporary work visas (which Jacinda kindly converted over 200,000 of them to PR in 2021 for no reason). So those who came in under Labour won't be going home they will be going on the dole along with all the Kiwis, because PR entitles them to welfare benefits.

True, but there’s also still plenty on work visas, or on working holiday visas

Interesting piece.

The dominant economics view for the last 50 years is that managing the risk of inflation is mainly achieved by stopping the labour market over-heating. Obviously, workers having the power to demand more wages is far too big a risk etc etc - prices and wages will 'spiral' out of control.

What confuses me about this position is that it demonstrates a lack of trust in the free market, which is otherwise feted (worshipped even) by economists. Let's look at two examples.

Firstly, as the article notes, when labour gets more expensive, firms invest in labour-saving technology and this increases productivity (and lord knows we could do with some of that here). The UK industrial revolution was driven by businesses having to pay higher wages than countries like France, India etc (see invention of the spinning jenny). In NZ, we panic when the cost of labour goes up and slam on the interest rate brake, or open the door to cheap as chips seasonal workers. As a result, we have terrible productivity and other countries are years ahead of us (eg Netherlands food growers).

Secondly, when labour markets are tight, workers can choose a job more freely and this leaves some jobs unfilled - e.g. nightshifts in care homes, retail work, 10-hour shifts picking vegetables in the middle of nowhere. Errrm, hello, these jobs are not paying enough - the market is telling us that clearly. Let the market do its thing! If that means that the cost of aged care or clothes goes up a bit, or that we lose businesses that are only profitable if they pay slave wages, then good. That seems a much fairer way to 'loosen the labour market' to me.

Exactly right. And what we should actually strive for going forward is being OK with slightly higher levels of inflation (around 1-4% should be the band IMO) along with higher interest rates. Higher interest rates = better productivity over the long term for the reasons Jfoe talks about and it ensures a reallocation of capital and labour more favourably to higher productive industries. That comes with some pain, but encourages education, training, investment in R&D, more competition and investment in better equipment etc. That's a FAR better place to be than a low interest rate environment, which causes massive asset speculation, zombie companies and terrible productivity. Yes, it forces some flux in the labour force too, so higher levels of unemployment, but with the right education settings, that unemployment isn't "sticky", i.e. people retrain and continually level up their skills.

Enjoyed the article. One of the reasons that economic growth has been so sluggish is that we are increasing the number of jobs in sectors with very low productivity growth, like health and aged care, more rapidly than we can create efficiencies in other industries.

The demographic changes underway will have wider impacts than just the labor market as well. As we increasingly move to start drawing down retirement savings the investment landscape will alse change.

This article does imply HFL. It’s hard to know whether we will be low on labour or low on demand.

The great labor crunch will be solved the way it always has ... by importing cheap labor.

Having been in Europe lately this is the real issue. In the richer countries everyone is short of labour. It's only going to get worse and in reality we are entering uncharted territory as the modern world has never faced this before. There's some labour but a lots unskilled.

We need to be very careful here as the options for young, skilled people are growing. Higher incomes, more interesting work and better lifestyle, im sorry but NZ does not have a monopoly on nice landscapes etc - the only thing we do have is space and less crowds. Most of Europe was cleaner re water, rubbish, than NZ I'm sad to say.

Get a good education, and again a lot of NZers don't value this, and the world will be yours. Did our pollies talk about education in the election???

Come on. you lot. You're all smart - why has nobody asked the question?

Surely it's output PER HEAD that is the metric. TOTAL is an irrelevance - but that irrelevance drives dumb immigration policies.

Come on...

Wealth per-head is always better with less heads; more of everything each. Why were we so stupid? Oh, that's right, we worship economics...

Agree but if us oldies have thrown in the towel and my output is zero we have less people to do the same amount. In fact the ones left maybe/are more productive but I'm not, and don't intend to be, so the average per person can go down!!!

We will need more per person to stand still or is my logic wrong?

With respect - and I have a lot for your posts (I planted my own forest by hand, and don't try and cash-in on the ETS; I do it altruistically) - I think it's wrong. Fossil energy equates to about 4.5 years hard yakka; at 100 million barrels A DAY, that's 4.5 million years of hard labour, PER DAY. And yes, I'm yelling! The difference is so orders-of-magnitude out, that ex fossil energy, ALL BETS ARE OFF.

You, with your ability to think, might get something out of Tom Murphy's Dothemath blogsite (he's an astrophysicist, who turned his thinking to existential questions). Download his free textbook, read it, then read his posts since. The social construct humanity puts together in place of this one, will be very, very different. We wil probably care when we are able, be cared for when not, in a rolling generational maul - as happened until 5,000-odd years ago.

Learning that money is not a store of value, will be a whistle-stop station we pass on the way...

Thanks I’ll have a look at that.

I agree with no or much less fossil energy things radically change. I saw an article showing that Lufthansa would need 75% of Germanys electricity to produce enough hydrogen to operate as now. Well that’s not going to happen there or anywhere, and Germany is already covered in windmills and Solar, so where to?

I suppose it’s so daunting that you say it just can’t be real!!! but the laws of physics, chemistry and maths are still the same when I last looked.

There's a certain type of individual, drunk on human exceptionalism and mesmerised by the power of dilithium crystals to colonise the galaxy, that just can't take a step back and ask themselves, why? They forge ahead, commiting the functionality of our biosphere to be increasingly supported by hi tech props, while dreaming of spreading human extractivism across the universe.

I just hope fusion never becomes viable, because that allows the bs to continue, until the last gasp of complex life on Earth. The Fermi paradox in action!

PDK - I've been having conversations with people and organisations this week about preparing for degrowth, labour challenges and other complex human system challenges of the now nearish-future and it is something most people (and leaders) can't even imagine.

Would you consider doing an article about how you see this might look in the business context, the impact on skills and labour needed etc.? I all because I suspect you've also spent time looking at how this might shift once (for example) petrol is $10/L but people are still being paid $25/hr. Organisations spend so much time tinkering around the edges but can't imagine anything other than a non-radical future/ same as usual. So we need people who can imagine different so that others can also imagine those better futures and see a pathway forward into them.

Economics in its traditional definition is pretty benign, it's just a certain sort of economics, yeasty economics, has become the favourite among the elite, and now occupies the royal astrologers comfy chair.

I'd suggest that all these economies with so called low unemployment are due to fudged employment figures.

At least 20% would be my guesstimate.

"tight labour markets will be a defining characteristic of the global economy over the coming decades" So AI isn't going to replace the workforce then?https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2023/03/31/goldman-sachs-predict…

Except for highly skilled occupations, NZ has an on-tap labour force called immigration. Our small population doesn't need a huge influx to top up the demand for more workers. We can simply import the labour needed to replace our aging population.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.