By David Skilling*

I’m finishing this note up on a 24 hour flight back from Auckland to Amsterdam after two weeks in Asia, talking to government officials, firms, and investors. This note contains some reflections on economic and political developments in Asia.

Economic outlook

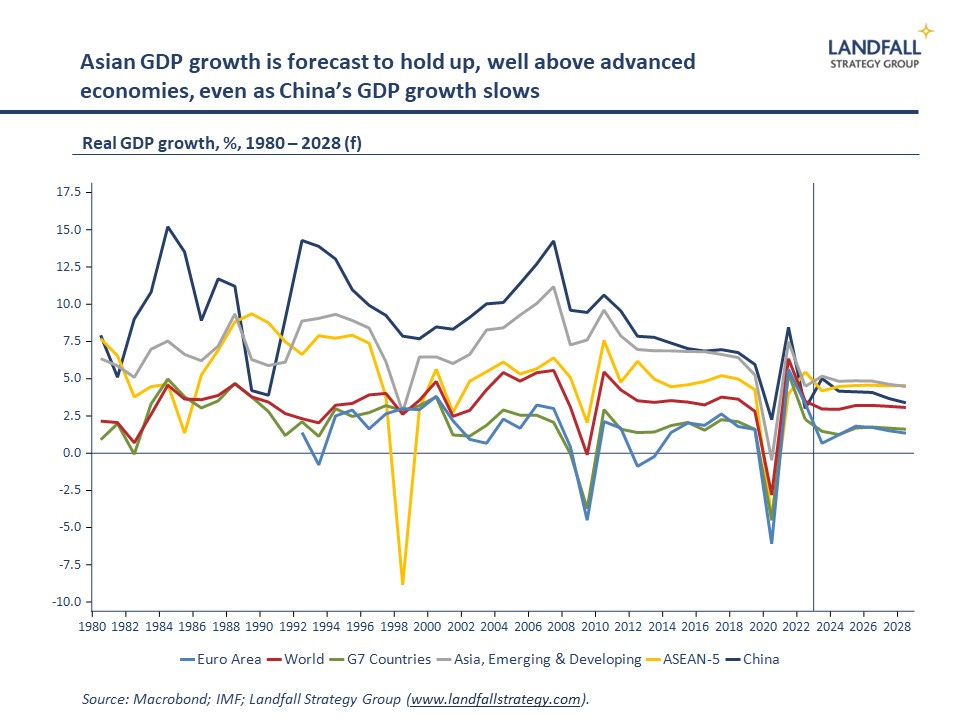

Previous notes have described the weakening economic outlook across Asia; recent World Bank forecasts for Asian growth were the weakest in 50 years. However, relative to my home base in Europe, there is a sharp sense of economic dynamism. Last week’s, IMF forecasts of growth rates across Asia were robust compared to other regions of the world – even if lower than usual.

From India and Japan to the ASEANs, there are relatively strong growth outlooks. Indeed, on IMF numbers, emerging and developing Asia will account for ~45% of global GDP growth this year, with China accounting for over half of that. Advanced economies account for about one third of global growth.

Singapore’s advance estimates of Q3 GDP growth came in last week at a strong 1.0% qoq. And the recent MAS outlook was more positive, reducing their assessment of the likelihood of a sharp downturn in Singapore. This is instructive because, as noted recently, Singapore is a canary in the mine of the global economy. Singapore is also investing tens of billions of dollars in expanding and upgrading its airport and ports, a vote of confidence in the future.

China’s economic outlook also looks better from an Asian standpoint. China’s economy faces deep structural challenges, from the real estate sector to a low consumption share of GDP. China’s GDP for Q3 came in this week at 4.9%, stronger than expected, but on an ongoing path to lower trend GDP growth. I am not a China bull, but some of the recent catastrophism about the Chinese economy is overdone.

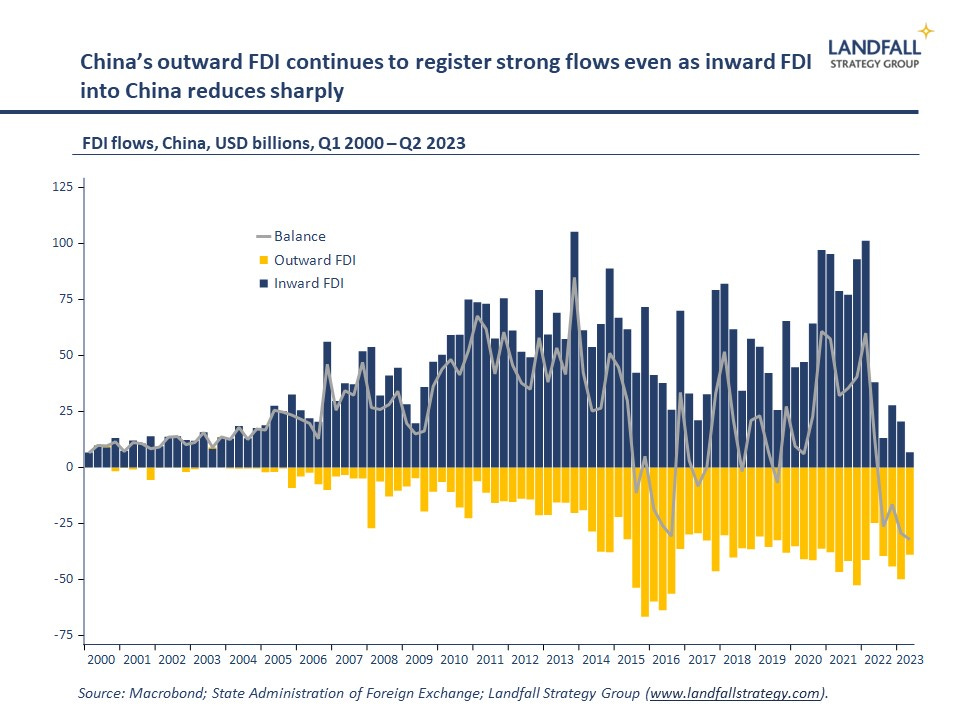

Across Asia, the growth drivers of the Chinese economy are evident. Chinese firms are increasingly expanding into non-Western markets, with substantial Chinese investment into ASEAN economies. Even as China’s inward FDI has reduced sharply, outward FDI has held up.

This is partly due to trade diversion away from China as firms relocate aspects of their supply chains to avoid tariffs and other trade/investment restrictions. But it also reflects the international growth of Chinese firms in sectors such as fashion and auto. For example, Singapore has seen an influx of Chinese firms relocating – including some looking to benefit from the Singapore brand by presenting as Singapore firms, such as Shein and Nio (‘Singapore-washing’).

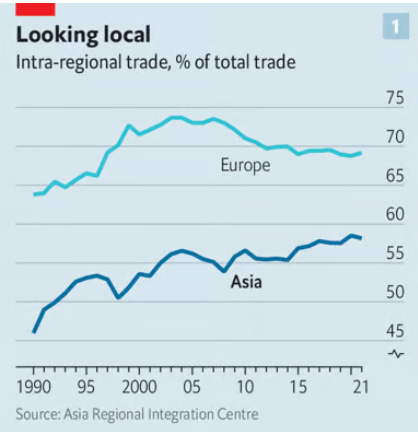

There are real risks in Asia relating to global economic fragmentation. East Asian economies have been primary beneficiaries of intense globalisation over the past few decades, and are exposed to emerging frictions on global flows. Asian export growth has been relatively weak over the past year, on weaker world trade. But intra-Asian and intra-ASEAN trade is doing well, suggesting new patterns of trade growth.

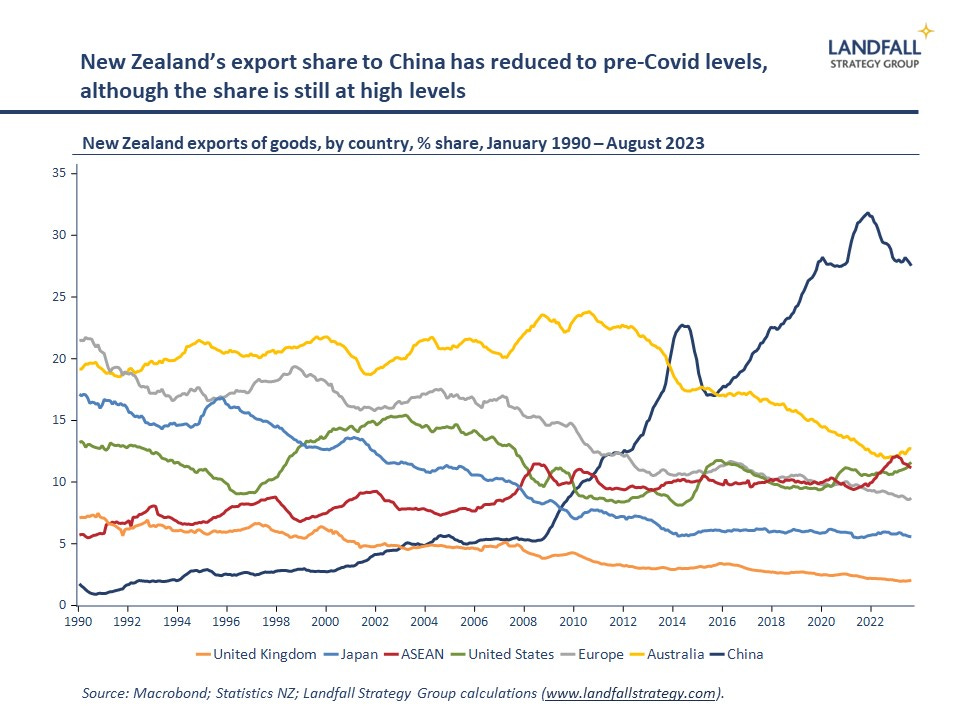

My longstanding view is that deglobalisation is exaggerated. Globalisation is changing not ending, with a more regional, political pattern of global flows. There is increased trade between China and ASEAN; reduced trade between China and Japan/South Korea; and so on. Even New Zealand’s exports are shifting in profile, with a reduced share to China (still high) and an increased share to ASEAN.

Geopolitical rivalry

Overall, the economic situation in Asia is resilient so far. The more concerning set of issues relate to geopolitical risks. For all of the current political and military conflict in Europe and the Middle East, the eastern end of Eurasia remains a key locus of geopolitical tension.

Asian economies have benefited from the geopolitical stability over much of the past several decades, which has supported strong economic growth. But this is changing rapidly for a few reasons, with growing risks.

First, China has become much more assertive over the past 15 years. It has decided on a new approach, responding to what it sees as Western weakness after the global financial crisis and populist advances in 2016 (see this book for a good account). But this has not been well calibrated, and there has been Chinese diplomatic and military over-reach.

From wolf warrior diplomacy to the ‘9 dashed line’ claim in the South China Sea and border disputes with India, China has created tensions across the region. This is reinforced by President Xi’s ambitions and autocratic style. These Chinese behaviours, with a consequent impact on geopolitical tensions across the region, are likely to continue - punctuated with periods of tactical moderation.

Second, strategic rivalry between the US and China has stepped up over the past two years. The Russian invasion of Ukraine marked the ‘end of the beginning’ of this geopolitical rivalry, with much sharper competition emerging: trade and investment restrictions on an expanding array of goods and technologies. This is leading to friendshoring and economic fragmentation, which is creating stresses across the regions as economies come under increasing pressure to make choices. Note the Belt & Road Initiative meetings in Beijing this week, with Presidents Xi and Putin offering an alternative to the Western-led order (and professing their ‘deep friendship’).

In this context, there is concern about US commitment to Asia. Although the Biden Administration has done a good job of strengthening alliances and relationships in Asia, there is concern about the ongoing populist turn in US politics, particularly in the Republican Party. As I noted recently, a second Trump Presidency would be more unilateral and transactional – and less invested in relationships.

Even short of this, there are concerns about the stamina of the US. The US is deeply engaged in supporting Ukraine against Russia. And the US is now directly involved in supporting Israel as well as trying to reach some resolution to the conflict in Israel/Gaza – and to stop the spread of the conflict across the Middle East. Two aircraft carrier groups are stationed off Israel’s coast, as well as a good chunk of the bandwidth of the US diplomatic machinery and President Biden.

The distractions of this ‘two front’ situation complicates the ongoing US ‘pivot’ to Asia. This will create exposures across Asia, and may encourage further Chinese adventurism.

In a recent speech (well worth reading), Singapore’s PM Lee said:

The Americans have been a major force in Asia since at least the Second World War. It is now nearly coming on 80 years. And they remain welcomed. I mean there are times when people talk about the Ugly Americans. But given that it is 80 years — two and a half generations, three generations — actually the Americans have been dominant in this region, while giving countries space to grow, to develop, to compete with one another peacefully and not to be held down or squatted upon. And that is why they are still welcomed after so many years. And if the Chinese can achieve something like that, I think the region can prosper.

Overall: it’s the politics that matters

There are multiple economic challenges facing Asian economies, as their economic models are confronted with a fragmenting global economy, aging populations, and so on. But in general, my assessment is that there is a reasonable measure of economic resilience across Asian economies.

It is the broader geopolitical risks that have the potential to derail Asian economic performance. Asian economies are directly exposed to big power strategic competition, a more assertive China, and a more distracted and inward-looking US. Consequential choices will increasingly be required and there is a heightened potential for conflict, which creates material economic risks. In short, I worry less about the impact of a sharp slowdown or crisis in China’s economy – and much more about the economic impact of geopolitical rivalry.

For firms and investors (and governments) exposed to Asia directly or indirectly, understanding geopolitical developments around Asia should be a priority. Supply chains are only gradually relocating out of China, and most advanced economies remain highly dependent on China. What happens in Asia won’t stay in Asia.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

11 Comments

Excellent, balanced and insightful article.

Careful mate, many people here see anything "Positive" coming out of China as pure propaganda. Like I said a few days ago they really make us look 3rd world in 2023.

Again biased article from David favoring China! I would say Chinese GDP ( Economic) data are manipulated and not trustworthy. China is in tremendous problems with it's real estate and ghost towns.

Honestly I think the USA is in a far worse position. The USA debt total makes China's housing problem look insignificant. At least China has something to show for it, what does the USA have to show for the Trillions of debt ?

My suggestion to you is either buy a ticket to China imediately, or hear a bit more directly from people who really been to China.

Anything you hear from the western media is only half of the truth, if those were trueth at all.

There’s a big difference between the worlds largest producer of EVs and the bizarre reality of Wall Street. Increasing production is more important than what speculators think something is worth. If you want to see difficulties look at VW, Nissan, Ford & GM. Mitsubishi just failed in China and withdrew.

VW is the next to struggle to compete.

the Chinese EVs are sellign 2x the price they sell in China, and still much cheaper than those european cars. how can they ever compete.

I have seen that speech from Singapore's PM before and believe he is right. Some thing always fills a power vacuum. As we are part of Asia and will always need to deal with China, lets hope China continues promoting trade and prosperity. I believe they will.

Whatever happens NZ will just be swept along and try to manoeuvre into the best outcome for our nation.

We can only hope there is rational leadership.

Joined a presentation with KPMG Consulting in an undisclosed ASEAN nation on Thurs. Expectations of strong growth out of Asian nations have well and truly gone.

Two aircraft carrier groups are stationed off Israel’s coast

Considering Ukraine is not far away from Israel, but did anyone see those aircraft sailing over there? US is just pinching the soft peaches, and soft peaches only.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.