By David Skilling*

In this week’s global briefing:

1. Geopolitics & China’s recovery: Trade and investment restriction are imposing costs on China’s economy. China may try to have these relaxed through diplomacy; but it is more likely to use its supply chain leverage to try to achieve this.

2. The end of Prigozhin: The death of Prigozhin does not necessarily strengthen Mr Putin. Division across Russian elites, combined with increasingly evident economic challenges in Russia, continues to raise the likelihood of tail risk events.

3. 10-year rates: US 10-year government bonds are the highest since 2007, on strong growth and persistent inflationary pressures. But the costs of returning inflation to target may lead to a more relaxed policy approach by the Fed, causing rates to fall.

4. BRICS+: The expansion of BRICS, adding 6 countries, will not lead to a more coherent organisation. But it reflects the hedging behaviour of significant countries in the global south. Global leadership is increasingly contested.

5. Small economies & slowing trade: Strong small economy performance through the pandemic was partly due to strong world trade growth. But there is now economic slowing across multiple small economies as world trade growth normalises.

1. Geopolitics & China’s recovery

There are many reasons for China’s weak economic recovery and its relatively modest economic outlook (at least by China’s high standards). Deep problems in the real estate sector and associated financial institutions, precautionary saving by risk averse households, and sluggish demand for industrial goods dampening China’s exports are just some.

And over the medium-term, China’s unwinding demographics, its structural productivity challenges, as well as its debt overhang (which has similarities to a balance sheet recession), will combine to drag on economic performance.

Although President Xi runs a security first approach to policy, and a full-fledged economic reform effort is unlikely under his leadership, weak economic outcomes will undermine the legitimacy of his regime. High youth unemployment (21% at last count, before the series was discontinued) and weakening real estate prices are political risks. The exhortation to ‘eat bitterness’ does not resonate with a generation that prefers to ‘lie flat’.

Which brings us to geopolitics. Another reason for China’s subdued economic performance is due to the trade, investment, and technology restrictions that have been imposed. Just over the past week or two, the US and Germany have announced increased investment restrictions.

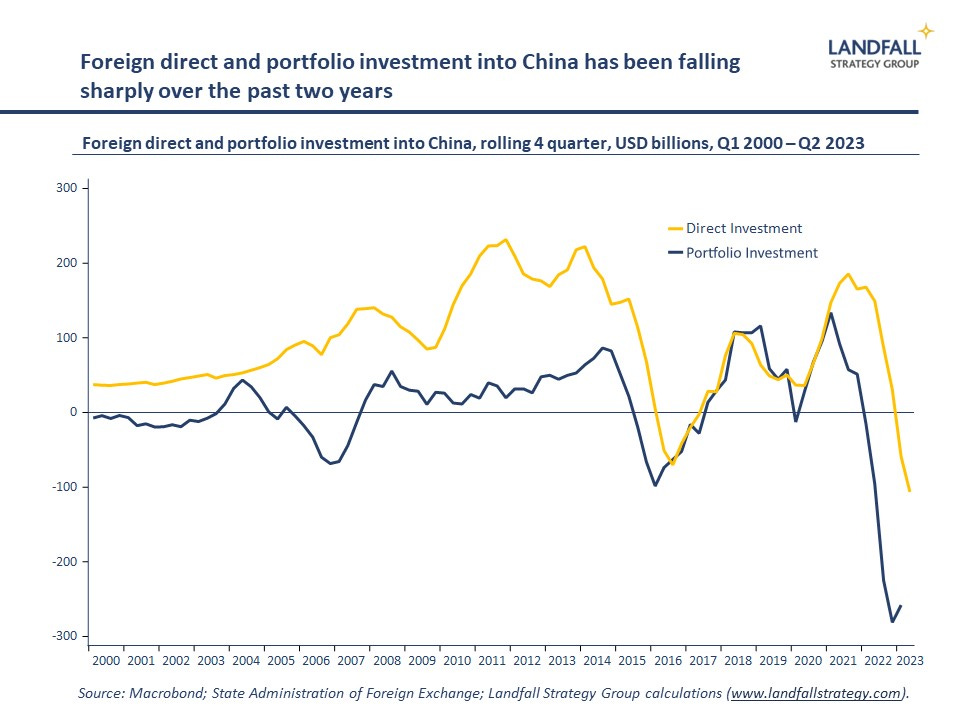

As discussed in recent notes, FDI investment into China is well down (particularly greenfields projects), portfolio capital inflows are contracting, and export demand from important markets is under pressure. And the inability to access key inputs – notably advanced semiconductor chips – is constraining China’s ability to develop strengths. Not all is bad: China has recently become the world’s largest car exporter. But these friend-shoring dynamics matter.

Another recent illustration of these geopolitical costs is the market response to Arm’s IPO prospectus this week. Chip designer Arm, responsible for 99% of the chips in the world’s smartphones, revealed that it generates ~25% of its income in China. This was higher than expected, particularly given the potential for further tech-focused decoupling. Arm’s indicative pricing is seen as ambitious by many investors because of this China risk.

Relaxing these restrictions on trade and investment flows is important for China’s economy. The question is whether China responds with stepped-up constructive diplomacy to win Western economies over (at least in Europe, if not the US) and toning down its aggressive rhetoric and actions. Or whether China uses its leverage in key parts of global supply chains (rare earths, batteries, solar) to force the relaxation of restrictions; note the recent measures to restrict exports of gallium and germanium.

Implications: Removing geopolitical friction from China’s economy will provide some economic support, and there may be some political pressure to do so. Mr Xi’s instincts seem to be to play hard ball, and the prospects of the US responding positively to a Chinese charm offensive, particularly as Presidential elections loom, seems low. So we should brace for more aggressive Chinese pushback against Western sanctions in an attempt to get them lifted, which will come at further cost to the global economy.

2. The end of Prigozhin

Exactly two months on from Wagner Group’s short-lived march on Moscow, Mr Putin looks to be (trying to) draw a line under it: Prigozhin’s plane fell out of the sky on Wednesday, killing him and several of Wagner Group’s leadership, and General Surovikin – formerly head of Russia’s armed forces in Ukraine, and a Prigozhin ally – was removed and is under house arrest.

Mr Putin is cleaning house, siding with the military establishment, and exacting revenge. And his virtual address to BRICS leaders on Wednesday was an attempt to project normality (even if the content of his remarks was Alice in Wonderland material).

But as with most things in Russia, this is unlikely to be as straightforward. The fact that the march happened at all weakened Mr Putin. Resorting to assassinating the leader (assuming that is what is happened) is less a sign of confident leadership than a symbol of fragmentation among the elite.

In the days after the mutiny in late June, my assessment was that these events had broadened the distribution of possible outcomes – with more weight on tail events and less on status quo outcomes, and likely with a positive skew. I think that is still right. The status quo in Russia seems unsustainable: widening conscription, ongoing casualties, regular drone attacks on Moscow, elite dissatisfaction, as well as the ongoing deflation in Russia’s economy.

As noteworthy during the week was Mr Putin’s directives to the Russian central bank to constrain capital outflows and to support the rouble – which has been under sustained downward pressure on a widening trade deficit and capital flight. The various sanctions are significantly constraining export revenues from the sale of oil and gas. The rouble recently broke through the 100 mark against the USD before recovering, partly on higher interest rates. It has been one of the worst performing currencies this year.

The sanctions – and the cost of a wartime economy – are causing growing pressure on the Russian economy. It may not have collapsed (always unlikely) but the economy has a slow puncture, which is getting worse.

Implications: The economic and political status quo is under growing stress in Russia, and something will have to give. Even if the war with Ukraine currently seems like an economic and military war of attrition, my sense is that we are entering a period when non-linear events are more likely. There will be economic and political forcing events in Russia. Despite the risks, this is likely net positive for Ukraine – and for exposed Western economies.

3. 10-year interest rates

As the world’s central bankers convene today for the annual Jackson Hole meetings, they face a challenging environment. Inflation is reducing, although it remains uncomfortably high, and interest rates are at elevated levels, even as economic activity is slowing in many advanced economies.

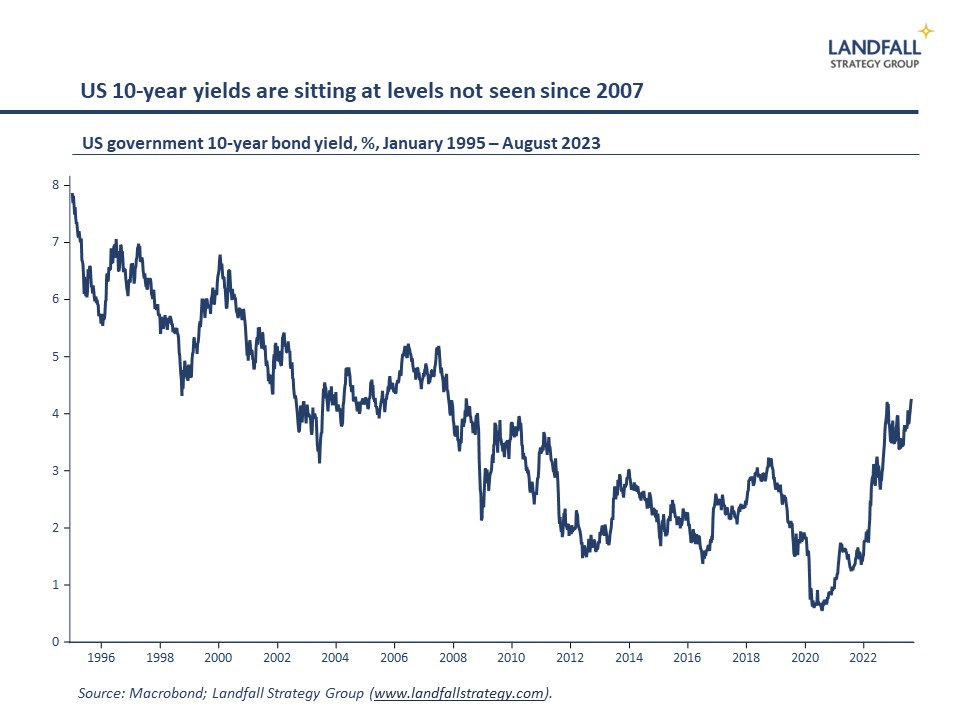

The US 10-year government bond yield, an important global benchmark for asset pricing, is currently ~4.3% - levels not seen since 2007, before the global financial crisis. This reflects the strength of the US economic recovery, with data continuing to positively surprise; soft landing or no landing scenarios are increasingly the consensus view, despite the lack of historical precedent.

And it also reflects growing structural inflationary pressures. Although some of the transitory supply-side shocks associated with the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are fading, there are a series of structural factors that will keep inflation higher for longer: growing frictions on global flows, labour market shortages and imbalances, as well as fiscal impulses associated with strategic competition (industrial policy, military spending, and so on). Getting inflation back to 2% will be a challenge for many central banks.

These high interest rates – in the US and elsewhere – are having an impact: slowing consumer spending, weaker credit growth, reduced house prices, increased government debt servicing costs, and so on. And given the centrality of the USD, high US interest rates and the strong dollar will have a global impact: on world trade growth, on the ability of emerging markets to access financing, and on economies that manage their exchange rates against the USD (including China).

The outlook for the 10-year rate is shaped by the policy response function as much as by the economic outlook. My view is that the costs associated with driving inflation back to target (2%) on a sustained basis will be high given the higher inflation environment that many advanced economies are entering.

There is likely to be growing economic and political pressure to run monetary policy a bit looser than would otherwise be the case, to reflect this changed environment. Rates will remain higher than they have been over much of the past 15 years, just not as high as they might be.

Practically, this means that central banks will be more prepared to gradually move towards 2% and to remain above this target level for some time. It is unlikely that any change in de facto target would be announced, it would become apparent over time. Eventually, there may be some renegotiation of the official target to reflect the new global economic context.

Implications: The US 10 year rate is broadly justified on the basis of economic fundamentals – growth is strong and inflationary pressures are persistent. But the rate is sensitive to a changed assessment of the policy response function. Greater tolerance of inflation by the Fed and others – an expectation of looser Fed policy – would justify a lower 10-year rate. It is a change in this policy function that is worth watching – at Jackson Hole and beyond.

4. BRICS+

At this week’s BRICS leaders’ summit in South Africa, a decision was taken to admit six countries from next year: Argentina, Ethiopia, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Up to 20 countries had indicated interest in joining.

This discussion was difficult because of the competing interests and preferences of the existing BRICS members. Most obviously, China is in favour of a larger grouping that it can steer and which acts as anti-Western grouping (as is Russia); India is nervous about exactly the same and has pushed back against an expansion of this type (as has Brazil). Indeed, it was not obvious than an expansion decision would have been taken at this meeting.

These differences aside, BRICS is clear about what it is responding to: Western dominance, the lack of a strong voice for the global south, USD centrality. The aim of many of the BRICS+ countries is to build options to generate strategic autonomy, hedging Western exposures and building options rather than being anti-Western. Indeed, the choice of members is interesting: Saudi and the UAE have strong relations with the US, as does Argentina.

This expansion reflects the growing desire for a collective voice on economic and political issues. And there is increasing economic and political activity between countries: growing trade and investment flows, food and energy deals, and so on, which will continue – often overlapping with relations with Western countries.

However, an expansion to 11 countries will make it more difficult to advance a coherent policy agenda: a BRICS currency is even more of a non-starter, for example, although expect more non USD-denominated payments within the group. BRICS finance officials have been tasked with identifying ways to reduce their reliance on the US dollar in trade among their economies.

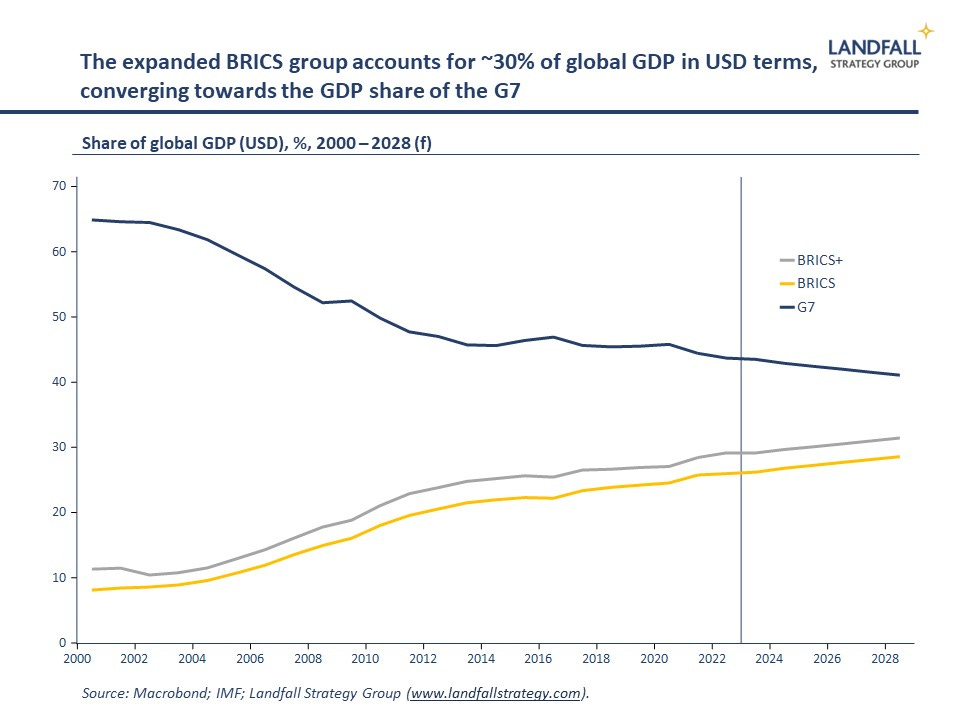

That said, this expansion should be taken seriously. BRICS+ accounts for ~30% of global GDP in USD terms (37% in PPP terms), converging to the G7 share, and contains 7 of the G20 members. It also includes a sizable share of global commodity supply and demand. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iran, Russia, China, and Brazil are substantial oil producers; China and India are major oil importers. And Argentina and Brazil, Russia, and others are major soft commodity suppliers. Over time, this may have an impact of commodity flows as well as the currency of commodity pricing and transactions.

It was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that gave the previously moribund G7 a new lease of life: it has become a coherent voice of the West. In this context, an expanded, more active BRICS is a response to a more assertive West on international economic and political issues – and a desire to create a middle ground.

Implications: BRICS+ is unlikely to become a coherent institution with well-developed policies and positions: it is too diverse and fragmented. But that is not the point. BRICS+ reflects a meaningful share of global GDP (and population) that is actively looking for new options in the Western-led global system. There will be an increased intensity of engagement between BRICS+ countries. The West remains the single largest node of global economic and political power, but it is an increasingly contested space.

5. Small economies & world trade growth

Small advanced economies performed strongly through the pandemic and since, generating superior GDP growth rates. Part of this was due to effective Covid management (small economies dominated the rankings on Landfall’s Covid Performance Index) as well as the ability to provide strong measures of fiscal support because of healthy government balance sheets.

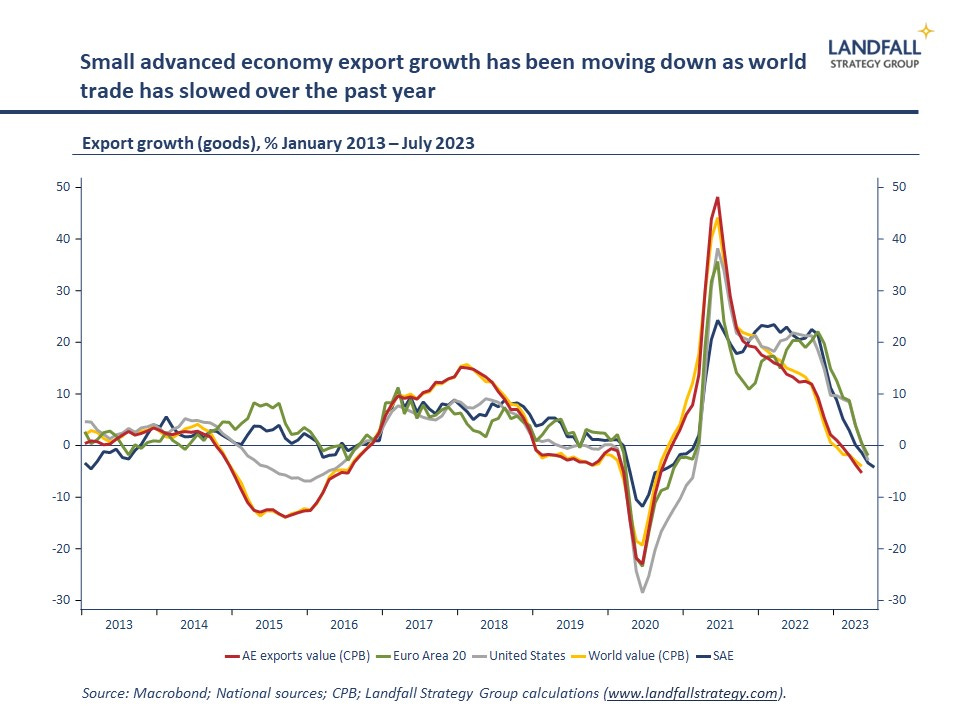

But small economies also benefited from the rapid recovery in world trade; export growth across small economies was strong, and this makes a meaningful contribution to headline GDP growth because of their high export shares (about double the export share across the OECD). But world trade growth is slowing (as discussed in a recent note) and the economic impact can be seen clearly in the economic data coming out of small economies.

Small economy growth is still positive, but has been decelerating through 2023. As examples, the Dutch economy moved into recession in Q2, with a 0.3% contraction qoq in Q2. This was driven by weakness in terms of exports as well as private consumption spending. Sweden reported a contraction of 1.5% qoq in Q2. Austria contracted by 0.4%, also on weakening external demand (note that Austria’s economy is tightly linked to Germany’s).

New Zealand’s export growth has also been weak, importantly due to slowing demand from China as well as lower commodity prices. New Zealand’s current account deficit has blown out to 8.5% of GDP in Q1.

There are some counter-examples. Ireland’s economic performance has remained quite strong, with ongoing export growth out of MNC-dominated sectors. And tourism-reliant countries (such as Greece and Portugal) have had a good summer, with tourism at or above pre-pandemic levels. This is providing a material source of external demand.

The open economic structures of small economies exposes them to external risks: their economic performance is sensitive to the strength of the global economy and of global flows to a much greater extent that larger economies. However, externally-oriented activity is the productivity growth engine of small economies – allowing them to overcome lower productivity in domestic sectors.

Implications: World trade growth is expected to pick up from next year, which will provide support to small economy performance again. Combined with strong competitive positions in global markets, I expect that growth in small economies will pick up over the course of the next year – even if this is an uneven process, with growing competitive pressures as well as an increased frequency of shocks.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

4 Comments

Mr Putin is cleaning house, siding with the military establishment, and exacting revenge. And his virtual address to BRICS leaders on Wednesday was an attempt to project normality (even if the content of his remarks was Alice in Wonderland material).

Isn’t it plain common sense that of all days, Putin would never have chosen Wednesday to act as spoiler when Russia’s prestige was soaring high in the international community? Again, the question arises: Who stands to gain? Link

National delusion is not in short supply.

In our systems of corporate democracy, war is an economic necessity, the perfect marriage of public subsidy and private profit: socialism for the rich, capitalism for the poor. The day after 9/11 the stock prices of the war industry soared. More bloodshed was coming, which is great for business.

Today, the most profitable wars have their own brand. They are called “forever wars”: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq, Libya, Yemen and now Ukraine. All are based on a pack of lies.

Iraq is the most infamous, with its weapons of mass destruction that didn’t exist. Nato’s destruction of Libya in 2011 was justified by a massacre in Benghazi that didn’t happen. Afghanistan was a convenient revenge war for 9/11, which had nothing to do with the people of Afghanistan.

Today, the news from Afghanistan is how evil the Taliban are — not that President Joe Biden’s theft of $7-billion of the country’s bank reserves is causing widespread suffering. Recently, National Public Radio in Washington devoted two hours to Afghanistan — and 30 seconds to its starving people. Link

Who stands to gain with Prigozhins assassination? Why the little mafia don in the Kremlin of course. The simple message of cross me and you're dead has been the overriding theme of his presidency, as evidenced by the list of dead people. Was the day of Prigozhins death special? No. Apart from the fact it gave Russian media something to bury the assassination with.

My view is that the costs associated with driving inflation back to target (2%) on a sustained basis will be high given the higher inflation environment that many advanced economies are entering.

So far unemployment has stayed low and GDP per hour worked is stable:

https://data.oecd.org/chart/7aq3

If we can go from 0.25% to 5.5% in two years why not 10% in another two. I don't see a reason not to hit inflation targets.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.