By David Skilling*

Across advanced economies, national growth models need to adapt to a rapidly changing world. Patterns of global flows and the locations of competitive advantage are shifting rapidly in response to geopolitical rivalry, competitive industrial policy, higher energy prices, and so on.

Many growth models are being placed under increasing strain. Change needs to happen fast.

Reflections from Germany & the UK

I have been in Germany this week, reminding me of the structural challenges facing Europe’s largest economy. From the unreliability of Deutsche Bahn, to airport delays and patchy internet, the under-investment in Germany’s core infrastructure was evident.

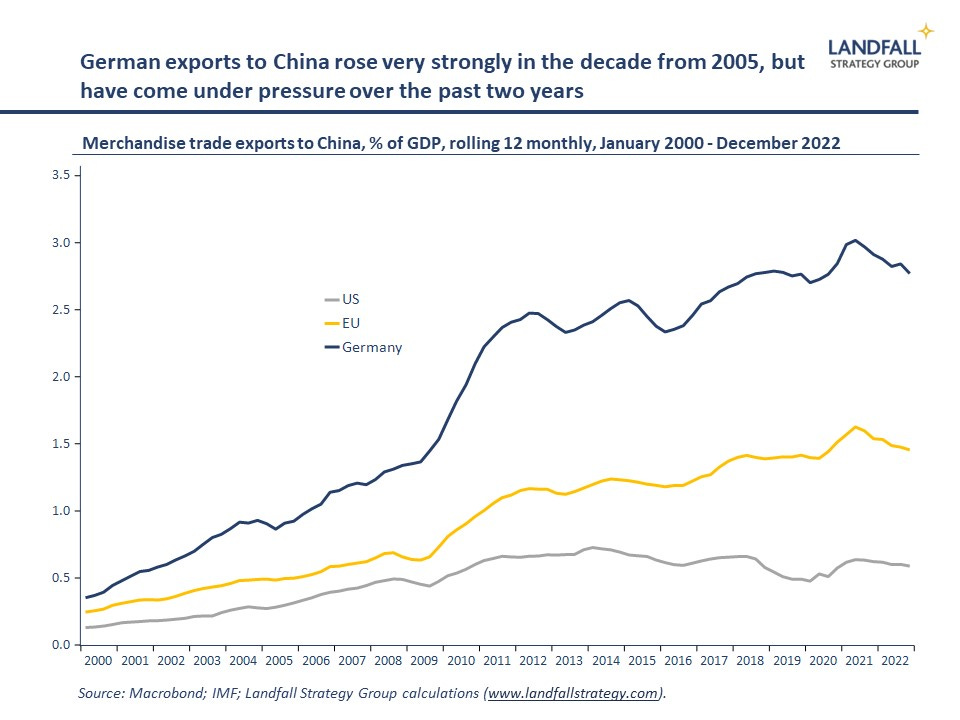

More fundamentally, Germany illustrates the deep challenges caused by global economic and geopolitical dynamics. From around 2000, Germany generated strong export-led growth on improved competitiveness and a presence in high growth industrial sectors. Germany grew its exports/GDP share from ~30% in 2000 to ~45% by 2012, holding its global export share steady. China was an important part of this growth story, with Germany’s goods exports to China reaching ~3% of GDP.

But Germany’s core industrial strengths are exposed to structurally higher energy prices as well as geopolitical frictions with China. And some of the commanding heights of the German economy (notably its auto sector) are under sharp competitive pressure from China: China has just become the world’s largest car exporter, with particular strengths in electric vehicles.

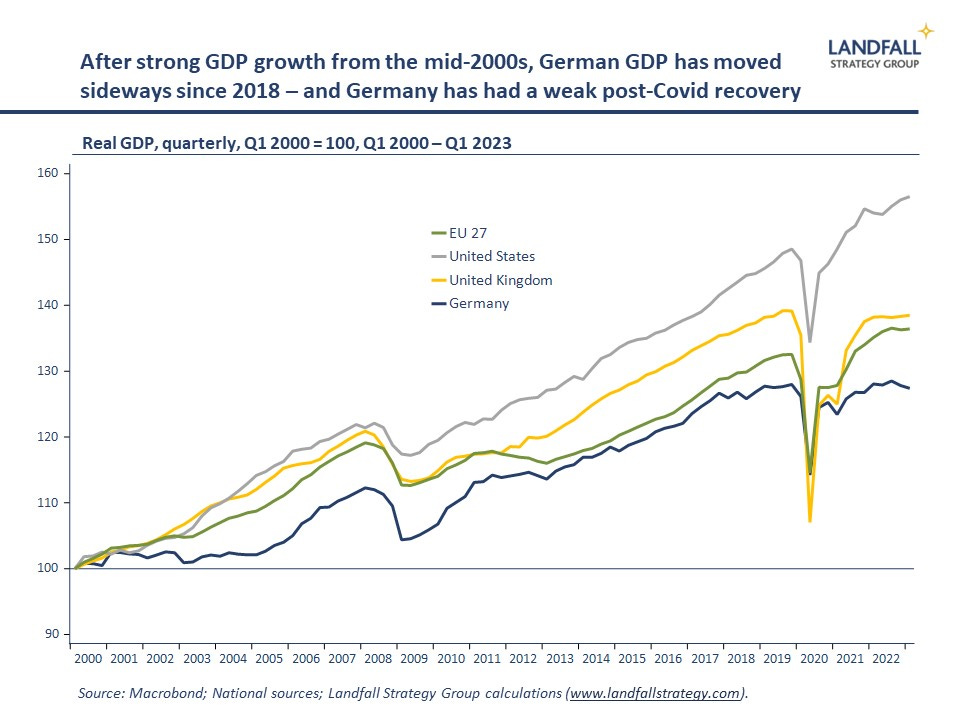

Germany is now in technical recession, with a GDP contraction of 0.3% qoq in Q1 following -0.5% qoq in Q4. Energy intensive industrial production (chemicals, steel, glass) has been hit hard by higher energy prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, down 12.9% in the year to April (while overall industrial production expanded by 2.7%).

Germany’s GDP is about the same as it was in 2018, and the outlook is weak on concerns about energy prices, demographics and labour shortages, as well as sector-specific challenges. Export growth (including exports to China) is under increasing pressure.

In response, Germany is taking out the cheque book. It is investing tens of billions in subsidising energy costs for energy intensive firms, accelerating the green transition, and attracting investment (including up to €10 billion to support Intel to build a semiconductor plant). But a more fundamental revamp is required. Germany’s growth model needs to be adapted to new realities, as was the case with Germany’s structural reforms 20 years ago.

This is also part of the backdrop to Germany’s uneven approach to China: Germany has a deep exposure to China, which is now challenged by the growing strategic rivalry. China is an important source of earnings and growth for many German firms, and they continue to allocate capital to China. The Mercedes Benz CEO spoke for many German corporates when he recently said that cutting ties with China would be ‘unthinkable’. In advance of the China/Germany summit in a couple of weeks, the governing coalition remains split on how hawkish to be on China.

Across the North Sea, the UK also has deep structural challenges: its GDP and employment has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels; productivity growth is low, reinforced by weak business investment (as in Germany); and inflation remains stubbornly high.

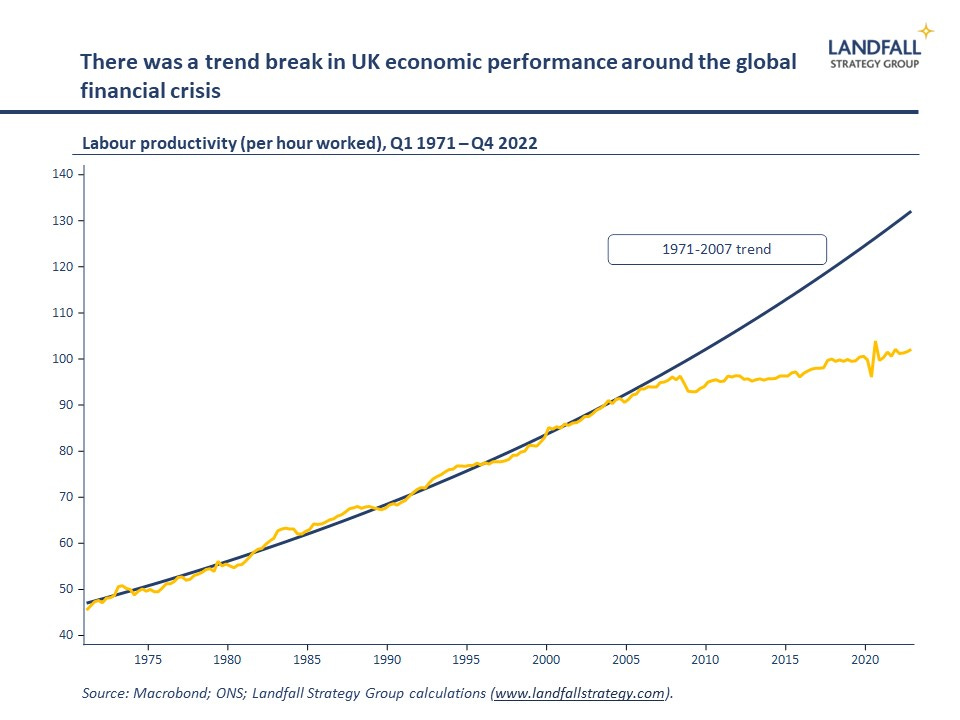

These structural issues are not new: on several measures, there was a trend break in economic performance around the global financial crisis – also seen in other economies. But Brexit is exerting an increasing cost on UK-wide competitiveness, hampering the UK’s ability to adapt to a new world.

London still feels dynamic and is a global draw. And the chaos of PMs Truss and Johnson has been replaced by a more competent, pragmatic Sunak government. But there is little evidence of a step change in policy – or performance. Looking forward, Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves recently delivered an outline of a prospective Labour government’s approach to economic policy, which was heavy on industrial policy. But more will be needed.

Without a meaningful policy response, European (and other) economies will continue to lose export market share and economic activity and can expect ongoing under-performance. There are political risks as well. Low growth (and inflation) provides space for populism to emerge; the far right AfD in Germany are now polling at 19%, for example, level with Chancellor Scholz’s SPD.

The US is a partial exception: it continues to out-perform, a recession is unlikely, and it is implementing a new economic policy approach to respond to new realities. The biggest risk is political, as we look to the 2024 Presidential elections.

There are idiosyncratic reasons for the performance of specific countries like Germany and the UK. But all advanced economies are exposed to growing stress on growth models due to emerging global economic and geopolitical dynamics; from frictions on global flows and competitive industrial policy to higher rates and a demographic reversal. Relying on existing growth models is unlikely to generate good outcomes.

Change can be particularly challenging for economies that have been successful in the recent past, like Germany. I call this the ‘policy-makers dilemma’, inspired by Clay Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma, where strong performance breeds complacency and dampens the perceived need to respond to new challenges. A culture of constructive paranoia is more useful at the moment.

Small can be beautiful

‘I feel the need, the need for speed’, Maverick in Top Gun

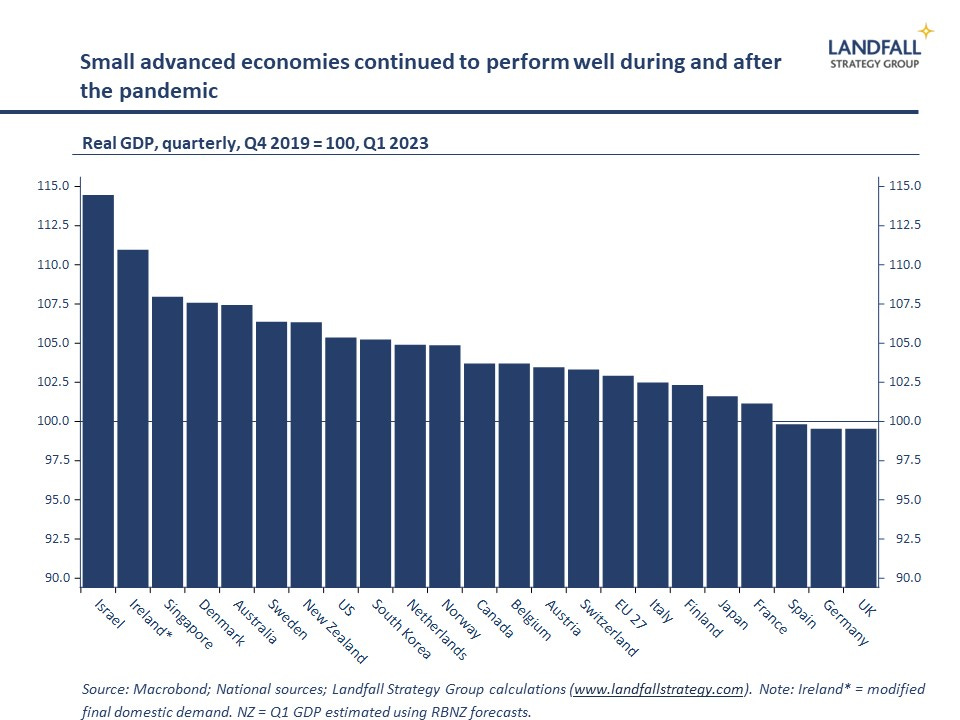

In contrast, smaller economies are responding more quickly – partly because their exposure to competitive pressures means that they have limited margin for error. They continue to deliberately position for a new world. From Dubai to Singapore and Ireland, small economies are attracting substantial inflows of capital, firms, and people. These economies provide attractive platforms for global economic engagement: a reminder that globalisation is not dead.

The sustained high investment in skills and innovation, strong infrastructure, and the ability to support key areas of economic strength, help small economies to adapt rapidly to changes in the global context. Many of the post-Covid economic policy shifts across leading small economies (Ireland, Netherlands, Singapore) have been to strengthen externally-oriented growth models, both positioning for new opportunities as well as reducing external risk exposures.

Of course, small economies are not perfect – housing markets are problematic in many small economies, from New Zealand to Ireland. But the strong external exposures of small advanced economies create a strong incentive to look ahead and to respond to structural changes. This explains the consistent over-performance of many small advanced economies over the past several decades.

I wrote recently that it was not clear that there were increasing returns to national scale in the emerging global environment. Despite claims that large economies were advantaged in an era of big power competition with frictions on globalisation, the ability of small economies to adapt in an agile manner is particularly valuable in periods of disruptive change.

A new global economic and geopolitical regime requires structural change to already stressed growth models around the world. There is a need for speed in adapting policy approaches to respond to new ‘wartime’ models of globalisation, competitive industrial policy, the net zero transition, disruptive new technologies, and much more. Many existing policy approaches and areas of competitive strength will be compromised in this new world.

This will place demands on policy-making capabilities. Assessing country outlooks is as much about social and political institutions as natural resources or sectoral strengths. There will be significant variation in the ability of economies to adjust to a new world. Bet on those that can adapt.

If you have not already, you can subscribe for free to receive occasional public notes - or take out a paid subscription for full access to these notes:

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

4 Comments

Of course, small economies are not perfect – housing markets are problematic in many small economies, from New Zealand to Ireland. But the strong external exposures of small advanced economies create a strong incentive to look ahead and to respond to structural changes. This explains the consistent over-performance of many small advanced economies over the past several decades.

Not sure where David is pulling this insight from or what he actually means. The NZ and Irish housing bubbles were caused primarily by credit creation. The Irish economy has 'outperformed' in some sectors such as food innovation.

Nive day for fish fingers.

The above list is interesting indeed.

Israel stands out to me. Highly educated, big on science & its development, cuts a lot of new code in very sensitive, high security areas, mainly as a result of their military training [dare I say compulsory military training] being literally surrounded by its enemies & in a state of permanent political acrimony of recent times, Israel is head & shoulders the world's leading small nation [pop under 10 million]. And this despite all their 'disadvantages'.

Ireland is built on American credit/investment mostly for access to the EU, with cheap Irish taxes & govt grants thrown in, but with Europe too on the down side of their own demography [the only thing keeping them going is the million African/Asian refugees per annum that find their way into the system] that may not be forever either.

It's always interesting to see NZ up there in these 'tables' but I'm never fully sure whether to believe them or not. Having lived through the covid bullshit & seeing how little real thinking went on throughout the west [as opposed to cut & paste from China] you're never quite sure who to believe these days.

Skilling is flying totally blind (and I've emailed him on this, and he's chosen continued blindness).

Globally, we hit the ceiling in 2005-ish. That inflection is in one of his graphics, but misunderstood. We are going over the top of a bell-curve, so adjustments to flatter and to downwards, will happen in unsmooth jerks.

Yes, we are adjusting. Yes, the pace of adjusting will accelerate. No, we will not cope smoothly with the pace of change.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.