BNZ's chief economist Mike Jones is offering some words of caution for people looking to 'go short' with their mortgage fixing options.

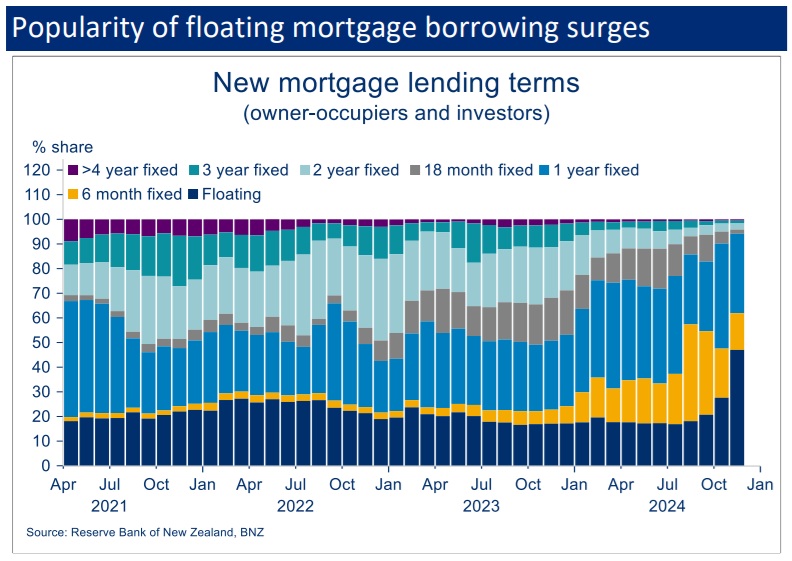

Reserve Bank (RBNZ) data for the month of November released recently showed that nearly half the new mortgage money in that month was on floating rates, while the vast majority of the rest of it was on short fixed terms.

In his latest Eco-Pulse publication, Jones notes that to date, going short has tended to pay off given aggressive RBNZ cuts to the Official Cash Rate (OCR) and associated falls in mortgage rates. The RBNZ has cut the OCR from 5.5% since August 2024 to a current 4.25%, with another 50-point cut widely expected next month.

He notes that the share of outstanding mortgage borrowing with a maturity of less than 12 months is now 81%. In data doing back to 1999 that’s only been matched once before, in 2011/12.

"Moreover, mortgage-holders will continue to benefit to the extent there are further reductions in the OCR along the lines of our forecasts. These imply, at face-value, six month and one-year mortgage rates falling below 5% by around mid-year," Jones says.

"At the same time though, we’re compelled to offer a few competing viewpoints. First, a borrowing strategy concentrated at shorter-terms means a higher share of future interest expense is ‘at risk’. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing of course. But it does increase exposure to any unanticipated shocks in a year in which we could see a few. The volatile start to the year in financial markets is a reminder of such," he says.

"Second, a swathe of Reserve Bank cash rate cuts are already factored into interest rates where they stand. This presents both risks and opportunities."

Jones says, for example, that expectations of a much lower OCR in six-months’ time means six-month fixed mortgage rates are about 1.3% lower than floating rates.

"Given this, we’re a little surprised the preference to float is so strong. Floating has the benefit of extra flexibility, but the large rate difference increases the bar to breaking even relative to fixing for a six month term."

Jones says that "chunky rate cut expectations" are also holding term mortgage rates like the two-year below those of shorter-terms.

He says this means that for the two-year rate to fall further from here requires not just the OCR be cut further, but that current expectations for more than 100 basis points worth of cuts are "dialled up".

"This plays to the grain of our view that there is still some downside in term (two, three year) rates but probably not as much as some think.

"It’s something to think about for those on short terms as they ponder an appropriate time to term-out some of their debt. Added to this is the fact that remaining on short-terms costs more upfront, with the ultimate benefit – being able to roll onto lower rates in future – uncertain."

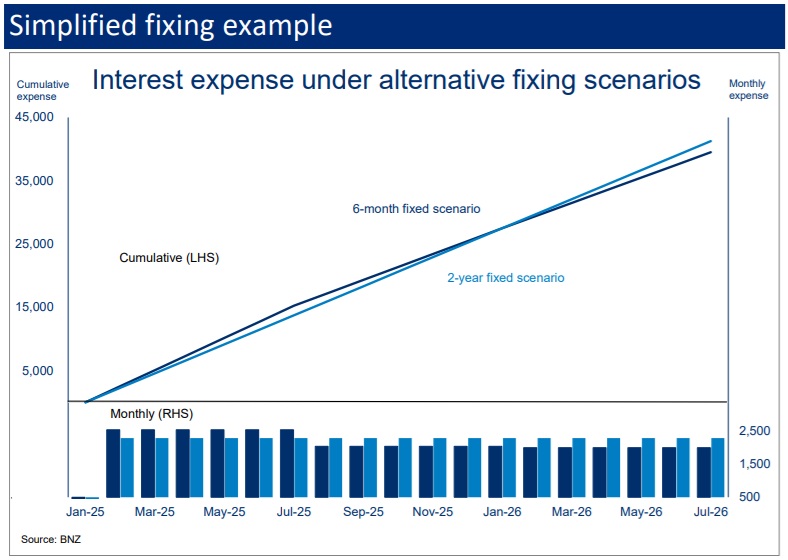

Jones provides a simplified example to illustrate the point.

"The chart shows the monthly and cumulative cost of fixing today for either two-years or six months on a hypothetical 500k debt. You can fix for two-years at the current rate around 5.5%, entailing a constant $2300 monthly interest cost. Or fix for six-months at a higher rate of around 6.1%, on the expectation you can hopefully re-fix at lower rates in future. In the chart below we’ve assumed the first six-monthly refix in August 2025 is at 4.9% and the second in February 2026 at 4.8%," Jones says.

"The chart shows that the cumulative interest cost 'worm' on the six month option eventually falls below the two-year one but: 1) it takes a while – until January 2026 – and, 2), that relies on the decent falls in six month rates we’ve assumed. This analysis also makes no allowance for the extra utility a borrower might get (sleep quality?) under the more highly hedged, two-year fixed scenario.

"The point is that, while mortgage borrowing for short terms may make sense given the potential for additional short-term rate relief, to us, fixing for tenors longer than a year does not look as unappealing as the current meagre demand would imply," Jones says.

"We’re only 22 days in but the fact that this year is looking particularly unpredictable highlights the point. There are risks aplenty."

5 Comments

From observation over the last ten years, the best course of action is to do the opposite of what the profit driven bank economist want you to do. With better online data available on borrowing, the public that bother to read, can see the truth.

Seeing as they are pushing their 2yr rate, does that mean you should go 6mths or 5yrs then?

That's my plan for a small chunk coming up for refix soon. 6 months then bundle it in with the next tranche that's up for refix in July, That lot might go 2years as I think it'll be close to the bottom in this cycle by then.

This analysis also makes no allowance for the extra utility a borrower might get (sleep quality?) under the more highly hedged, two-year fixed scenario.

Of course, the bank most definitely does value the extra utility they get for having a borrower locked in, with break fees that guarantee they can't lose.

Let's not - for even a moment - forget who is paying a bank economist's salary.

And in those spare moments, let's also consider whose interests comes first for a bank economist.

Would it be the bank's profits coming first? Or yours?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.