Piecemeal environmental reforms by individual countries are proving a headache for New Zealand exporters, according to the lobby group, Dairy Companies Association of New Zealand (DCANZ).

It would be far better if environmental reporting rules were set multilaterally, since over 100 countries take New Zealand dairy goods, DCANZ CEO Kimberly Crewther told Parliament’s Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Select Committee. But at present, exporters are often having to produce bespoke documentation for different countries, at significant cost.

“Countries are moving forward unilaterally in the absence of there being established global standards,” she told the Committee.

“We are making progress (towards uniformity), but the disparate nature of non-tariff barriers means that it is a job that is going to take many years to achieve.”

The Select Committee was hearing reports from a range of primary sector organisations on the way new trade restrictions rise up and replace tariffs which are being reformed away by Free Trade Agreements (FTA).

These trade restrictions come in two forms. One is the over-arching non-tariff measure (NTM), which includes benign rules on things like the sanitary conditions of traded products. But many NTMs morph into non-tariff barriers (NTBs), which block trade unfairly.

DCANZ is highly concerned about this problem. Its trade manager Elizabeth Kamber quoted from a Sense Partners report that estimates the cost of NTMs at $7.8 billion, or 30% of exports for the 2023 year.

"NTMs include sanitary and phytosanitary measures, technical regulations, packaging requirements, licensing, paperwork, price controls and many other requirements.

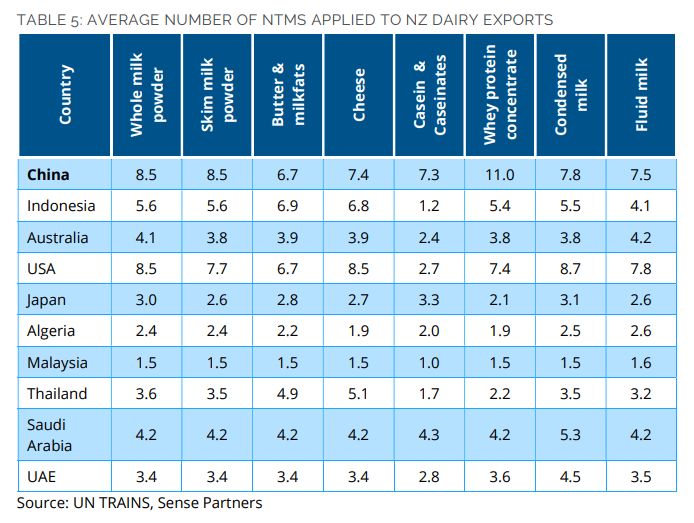

China imposed the largest number of NTMs, and other big markets like Australia, the US and Japan did lesser amounts.

Kamber is adamant not all NTMs are bad - some are necessary, for food safety or animal welfare.

“But these non-tariff measures become non-tariff barriers when they are not based on evidence or underpinned by science……they are becoming more common and they are becoming more complex,” says DCANZ trade manager Elizabeth Kamber.

She says NTBs include the need for on-site inspections when inspectors are not always available, specified technical requirements from particular countries, and variable labelling, packaging or shelf-life prescriptions from different nations. She argues this multiplicity of rule-making inhibits dairy companies from making products intended to be sold across a range of markets, and therefore constrain streamlined or synergistic manufacturing.

The lumber industry says it has similar problems with NTBs.

The Wood Processors and Manufacturers Association told the committee New Zealand’s nearest neighbour is itself an offender, by setting standards in the construction industry that match wood products supplied by its own timber industry, making it hard for New Zealand producers to sell wood products in Australia.

As a result, the forestry industry here is being penalised, despite its role in providing a ready supply of exotic wood, thereby assisting the conservation of indigenous forests, which the association says is a positive thing.

The Meat Industry Association also gave evidence at the select committee hearing. Its chief executive Sirma Karapeeva told the committee the red meat industry’s value as the country’s second most valuable commodity exporter had been greatly assisted by a series of free trade agreements that had reduced its annual tariff cost to $158 million.

“That said, of course, as tariffs come down, many of our trade partners are very sneaky, and they start to set up non-tariff barriers, or regulatory barriers, that inhibit trade. Those are becoming more prevalent, and they are also much harder to identify and deal with.”

Karapeeva says some barriers are legitimate but many add costs without adding any benefit, and the total impact on the New Zealand meat industry amounts to $1.3 billion a year.

The wine industry also worries about the impact of NTBs on its $2 billion dollar export business. The CEO of New Zealand Winegrowers Philip Gregan says it's impossible to calculate how much they cost to the industry, but it is a lot.

“Our wineries would have spent thousands of hours addressing the issue, as an organisation, we spent hundreds of hours.”

However, Gregan adds a rider – a Mutual Acceptance Agreement signed with assistance from the Government gives the industry some protection against red tape in vital markets like Australia and the United States.

Other submitters supported the principle of multilateral or plurilateral agreements to streamline regulations, which would give world trade a boost.

One of the most controversial NTBs is a requirement by the European Union (EU) that New Zealand meat and forest producers prove their output was not produced on land that was deforested after 2020. This rule is resented in this country since most deforestation took place in the 19th century and there has been net afforestation in recent years. Yet New Zealand would still have to produce mountains of paperwork, at great cost, to prove this self evident fact.

In the last few weeks, the EU has postponed its deadline for a year, but has not withdrawn the basic requirement in principle.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.