The Matrix of Drivers: 2022 Update report by the Agribusiness & Economics Research Unit at Lincoln University, funded by the Our Land and Water (OLW) National Science Challenge, presents a summary of the key changes and trends likely to affect land use in New Zealand.

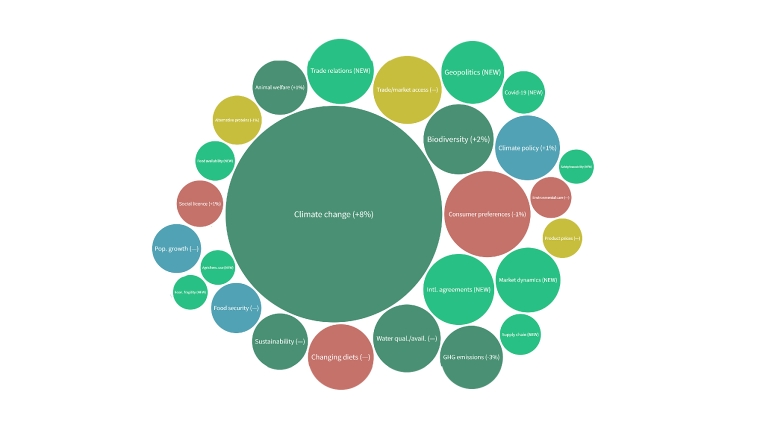

The purpose of the report is to inform OLW whose mission is to “enhance primary sector production and productivity while maintaining and improving our land and water quality for future generations.” It lists 35 challenges which have been prioritised by primary sector experts and the winner is – wait for it – climate change with a significant gap back to GHG emissions, condition of the environment and water quality. The report lists the other 30 in their finishing order, rather like a horse race.

AERU invited 2,818 sector experts, including agri-sector leaders, policymakers, and academics, to participate, received 622 responses and 251 completed questionnaires which at less than 10% of the original sample base is probably par for the course. The survey results were also analysed to reflect the views of those who professed to be very knowledgeable or knowledgeable about food exports i.e., mostly those working in the primary sector who comprised 30% of the respondents.

The research undertaken is very thorough, as it includes 1,500 international and domestic sources of information selected by an academic literature review process, covering central and regional government strategic and regulatory, primary sector group and farmer association documents, as well as international agency reports and academic literature.

The research also includes 83 international consumer preference studies which suggest attributes for which consumers are prepared to pay a premium, such as organic certification, although experience has shown consumers are less willing than they profess to pay a premium when it comes to the point of purchase. It also proposes less reliable areas of added value like regenerative agricultural production where product differentiation and consumer benefits are harder to prove.

Responses to domestic, as distinct from international, drivers of change differ slightly with water quality being seen as a more important issue than climate change, followed by the environment, agricultural policy and GHG emissions. Other issues to increase significantly in importance since the previous report in 2019 are extreme weather events, Māori values, cultural values and soil quality, while product attributes that are seen as earning greater returns from lower production include high quality, low environmental impact, food safety, and low carbon footprint.

The report identifies eight main categories of future trends and challenges that the research team see as having high potential to affect New Zealand land use change in the next few years: climate change, New Zealand’s environmental policy, Covid-19, global trends and challenges, emerging technologies, innovative products and new food technologies, international trading environment, and consumer trends.

Unsurprisingly extreme weather events, the launch of the Global Methane Pledge, COP26 commitments, and the introduction of GHG targets are all seen as heightening the challenge of adapting land use to cope with climate change. This will be further exacerbated by environmental policy, including freshwater management and Council designation of Significant Natural Areas on private land. The continued impact of Covid-19 on supply chains and labour supply is mentioned as a challenge, but the resilience of the primary sector and potential supply chain adjustment to logistical disruptions will undoubtedly reduce the likely impact on future land use.

The volatility of commodity prices and inflationary uncertainty are mentioned as continuing challenges, as well as the handling of food waste, although population growth is regarded as likely to drive the growth of protein consumption. Logically the report considers the emergence of new technology, such as electric farm vehicles, blockchain, autonomous and robotic systems, precision agriculture, GHG mitigation technologies, gene edited crops (New Zealand’s objection to GM is noted as an obstacle), and regenerative agriculture as trends that will encourage changes of land use and presumably farming operations.

Innovative products and new food products, such as alternative proteins and cellular production, combined with changing consumer tastes – less meat consumption, online shopping, desire for proof of sustainability, cultural values, and provenance – are also expected to land use change, although this is somewhat at odds with the predicted growth in traditional protein consumption.

The report notes that a 2018 study estimated 1.74 million hectares in New Zealand as being suitable for growing plant protein crops which surprisingly represents about 13% of the farmed total, three times as much as is currently in arable and horticultural production. This would presumably come from existing pastoral land. However the present legislation which encourages carbon farming is far more likely to drive land use change than a sudden upsurge in alternative proteins.

The international trading environment, incorporating new trade agreements and geopolitical tensions, will also present challenges, although New Zealand’s trading relationships and adaptability will minimise any sudden disruption of the farming sector and land use. The report’s authors assess all the trade agreements which New Zealand already has in place or is negotiating, but realistically the biggest impact to land use would arise if one of our largest markets were to be closed to imports from here for any reason. The present level of dependence on China for a large proportion of agricultural exports makes New Zealand sensitive to any political fallout from a dispute between the world’s great powers.

This is a very detailed and well researched report, although it leaves me with an irresistible impression of a document produced by academics and scientists for academics and scientists, rather than for farmers, processors and exporters operating in the real world. It will be interesting to look back in 15 years’ time to see who was right.

Current schedule and saleyard prices are available in the right-hand menu of the Rural section of this website.

P2 Steer

Select chart tabs

18 Comments

I wonder what % of land was in arable crops ,in say 1960 ,and 1980? I wasn't borne in 1960 , but from my school geography , a larger portion was. By 1980 , i think there was still the Rangitikei and Canterbury plains been largely cropping. Or rather mixed, with drystock doing a rotation.

this might go some way to answering your question https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/land-area-per-crop-type?country=~NZL

actually this one is better https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/NZL/new-zealand/arable-land

Thanks. Huge drop from 1990 onwards.

The numbers in the first series look correct (first link) , but the numbers in the second series (second link) are total nonsense. The huge supposed drop of about 75% around 1990 simply did not happen. This is what happens sometimes when people constructing the series are statistical people who know nothing about the real situation on the ground. If they had known anything, they would have known that the statistical series they had constructed was nonsense. There are a couple of possible reasons for the error, and a fair chance that both occurred. The historical figures were probably in acres and also probably included all of the forage crops such as turnips and swedes. Even then the 'three million' figure does not really pass the sniff test.

KeithW

Thanks for pointing that out Keith. I must admit it was just lazy googling, i didn't really look at the 2nd figures closely. the only thing is that it looks like both links ultimately come from the same data source UN FAO https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.ARBL.HA?locations=NZ

as you said, that big drop around 2002 must be from some kind of categorical change.

the only NZ data i can find only goes back to 2000ish, surely this info must be available somewhere here...?

I reckon there will be hard copy information in Ministry of Agriculture reports in the Lincoln library but alas I don't have time to go searching as it would be quite some search.

KeithW

page 9 of this report has details from 1990 onwards but arable seems to be in with grazing...

solardb,

Back in the 1960s, most of the Canterbury plains were dryland sheep.

The better soils were mixed cropping which included an animal phase in the rotation. Most of that land is still in mixed cropping although the animal phase is often young dairy stock. Most of the dairying is on Lismore and Eyre soils, which with irrigation has replaced the dryland sheep. These soils have very limited potential for intensive cropping. Any cropping is typically for winter feed for cattle ,and typically consumed in situ.

KeithW

Thanks Keith,

Do you know where the large cropping areas prior to 1990 were? i'm sure around Marton was crops, but can't think of anywhere else in the North Island. And is Maize counted as arable crops?

See above. Those figures are nonsense.

My student days at Lincoln go back to the late 1960s and I was working on farms in both islands. Also, our farm management field trips covered both islands. By 1970 I was working for Ministry of Agriculture. So I have a fair idea as to the situation. Most of the cash cropping in those days was in Canterbury, although there was also some cropping in the Manawatu on, for example, the Kairanga silt loams and the Rangitikei loams.

Pre 1990 the area of maize would have been very limited. We simply did not grow it in those days, either for grain or silage, in any significant way.

KeithW

solar, Southland is often forgotten as a cropping province but it has a history of cropping (arable) and is still considered to produce the best oats in the world - so I'm told. ;-) The link below was written in 2014 but has some interesting land use change information on it. There appears to be a resurgence in oat growing again now, but to what extent now I'm not sure.

Arable crops have declined in Southland from 50,000 ha in the early 1900s to less than 10,000 ha by 2011.

https://www.es.govt.nz/repository/libraries/id:26gi9ayo517q9stt81sd/hie…

I do like my Harroway Oats . And I was aware there is quite alot of cropping in southland.

Could it be that hay was considered a arable crop , but the shift to silage was not counted as arable? it makes mention of temporary meadow???

Allan Barber concludes with the comment that he is left with the "irresistible impression of a document produced by academics and scientists for academics and scientists, rather than for farmers, processors and exporters operating in the real world"

As someone who has spent a lot of time in academia, but who also lives this stuff every day in the real world, I agree with him. My impression is that the real experts seldom answer these surveys.

KeithW

I agree with your last paragraph Allan, however with regards to this It will be interesting to look back in 15 years’ time to see who was right. I would offer this "Success is not predicting the future. It's creating people who can thrive in a future that can't be predicted".

Abit like arguing with the wife , been right only seems to get you in trouble.

I do hope we get some positive progress, with the current challenges turned into using the advantages NZ naturally possesses. Hopefully , we get a compromise between farmers and the govt , and a big stick is not needed.

I don't see where "ideas for practical application" were actually asked for ?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.