We are approaching the end of the debt Train Wreck series. I’ve spent several weeks explaining why I think excessive debt is dragging the world economy toward an epic crash. The tracks ahead are clear for now but will not remain so. The end probably won’t be pretty. But there’s good news, too: we have time to get our portfolios, our businesses, and our families prepared.

Today, we’ll look at some new numbers on just how big the problem is, then I’ll recap the various angles we’ve discussed. This problem is so big that we easily overlook key points. I hope that listing them all in one place will help you grasp their enormity. Next week, and possibly a few after that, I’ll describe some possible strategies to protect your assets and family.

Off the Tracks

Talking about global debt requires that we consider almost incomprehensibly large numbers. Our minds can’t process their enormity. How much is a trillion dollars, really? But understanding this peril forces us to try.

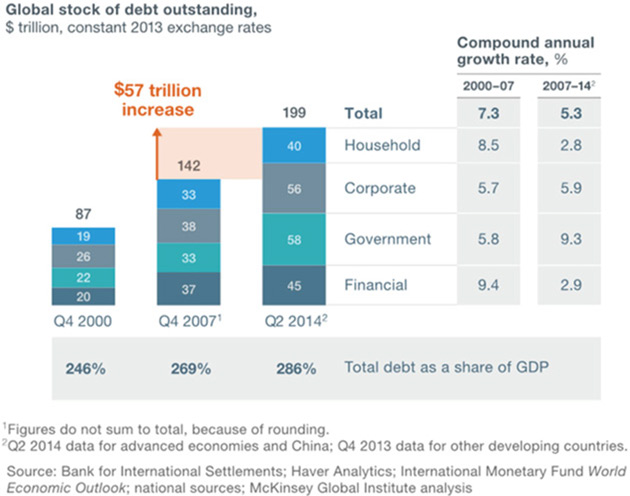

Earlier in this series, I shared a 2015 McKinsey chart that summed up global debt totals. They pegged it at $199 trillion as of Q2 2014. Note that the debt grew faster than global GDP. Everything I see suggests it will go higher at an ever-increasing rate.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

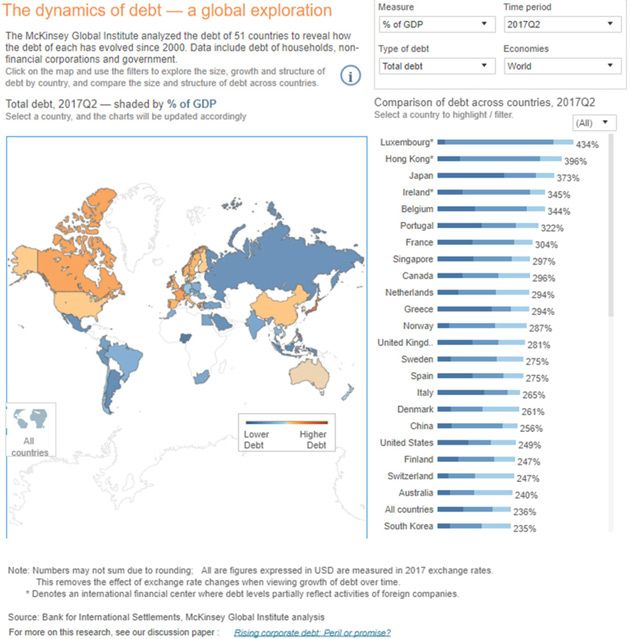

Last month, McKinsey published a very useful online tool for visualizing global debt, based on Q2 2017 data. It shows a total of $169T, which is less than McKinsey said in 2014. Is debt shrinking? No. The new tool excludes the Financial debt category, which was $45T three years earlier. A separate Institute for International Finance report said financial debt was $59T at the end of 2017. These aren’t quite comparable numbers, but in the (very big) ballpark range we can estimate total debt was somewhere between $225T (per McKinsey) and $238T (per IIF) in mid-2017. (IIF’s latest update last week says it is now $247T).

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

That would mean world debt grew something like 13% in the three years ended 2017. If so, it would be a slowdown comparable to the 2007-2014 pace McKinsey showed in the chart above—but still faster than world GDP grew in those three years. McKinsey says global debt (ex-financial) grew from $97T in 2007 to $169T in mid-2017.

Importantly, households aren’t driving this. Governments accounted for 43% of the increase McKinsey cites and nonfinancial corporate debt was 41%. That is where I think the coming train crash will originate. Governments have more debt than corporations, but also more tools (like taxing authority) to manage it.

On the other hand, governments also have massive “unfunded liabilities” that don’t show in the numbers above. So, they aren’t in a great position, either.

Bottom line: There’s going to be a train wreck here. Which train will go off which track is unclear, but something will. And we’re all going to feel it.

Woes to Come

We launched this journey in my May 11 Credit-Driven Train Crash letter. I described my friend Peter Boockvar’s perceptive statement: “We no longer have business cycles, we have credit cycles.”

His point is subtle yet critical. Post-crisis growth, mild as it’s been, has been largely a function of debt, which central banks encouraged and enabled. The result was inflated asset prices without the kind of “recovery” seen in previous business cycles. Interest rates, i.e. the cost of debt, thus became critical.

With rates now moving up again, premium asset prices are losing their raison d’etre and will stabilize and eventually fall. Peter Boockvar says this, not the conventional business cycle, is what will set off recession. That’s key. Lower asset prices won’t be the result of the next recession; they will cause that recession.I showed in that letter how companies will need to refinance about $4T of bonds in the next year, almost all of it at higher rates. This will hit debt-burdened companies that are already struggling and make it almost impossible for some to keep operating. Lenders, i.e. high-yield bond holders, will try to exit their positions all at once only to find a severe shortage of willing buyers.

The following week in Train Crash Preview, I listed the steps in which I think the crisis will unfold. They fall in four stages.

- The Beginning of Woes: Something, possibly high-yield bonds, will set off a liquidity scramble. It will spread through the already-unstable financial system and trigger a broader credit crisis.

- Lending Drought: Rising defaults will force banks to reduce lending, depriving previously stable businesses of working capital. This will reduce earnings and economic growth. The lower growth will turn into negative growth and we will enter recession.

- Political Backlash: Concurrent with the above, employers will be automating jobs as they grow desperate to cut costs. Suffering workers—who are also voters—will force higher “safety net” spending and government debt will skyrocket. A populist backlash could lead to tax increases that prolong the recession.

- The Great Reset: As this recession unfolds, the Fed and other central banks will abandon plans to reverse QE programs. I seriously think the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet assets could approach $20 trillion later in the next decade. But it won’t work because the world simply has too much debt. They will need to find some way to rationalize or “reset” the debt. Exactly how is hard to predict but it probably won’t be good for lenders, or for the holders of government promises like pensions and healthcare.

Next in High Yield Train Wreck, we dove deeper into the dream-driven high-yield bond market exemplified by this year’s nutty $702-million WeWork issue. I quoted Grant Williams, who wrote a masterful takedown of this craziness.

Ten years into the ongoing laboratory experiment being conducted by the world’s central banks, everywhere you look there are multiple examples of the kind of lunacy those policies have fomented by reducing the cost of capital to virtually zero and forcing investors to take risks they would ordinarily avoid in order to find some kind of return.

WeWork is one example of a company for whom, in the face of rapid growth, massive negative cashflows aren’t a problem, but there are plenty of others. Uber, AirBnB, SnapChat and, of course, Tesla have all captured the imagination of investors thanks to lofty dreams, articulated by charismatic CEOs—but the day things turn around and the economy begins to weaken or, God forbid, investors seek a return on their investment as opposed to settling for rolling promises of gigantic, game-changing revenues to come, it is over.

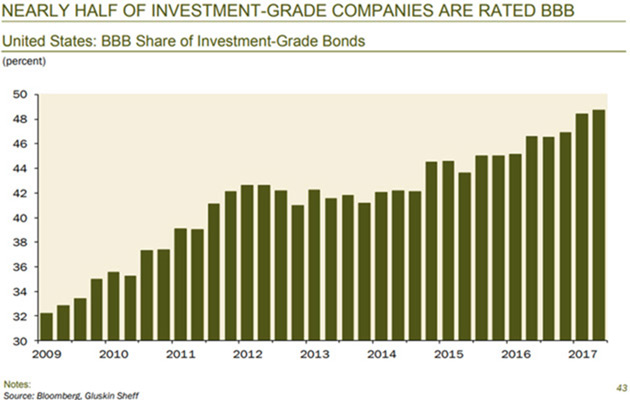

We went on to talk about the insanity of yield-hungry investors practically throwing cash at borrowers while demanding little in return. I also showed how this is not simply a junk-rated company problem, since almost half of investment-grade companies are rated BBB and could easily slip to junk status in a downturn.

Source: On My Radar

Growing Leverage

The week after we turned to Europe in The Italian Trigger . Unfortunately, Italy isn’t Europe’s only problem. The big Kahuna is Germany, which spent years offering generous vendor financing to the rest of the continent to entice the purchase of German goods. The result: a giant trade surplus for Germany and giant, unpayable debts for those who bought German goods.

The Euro currency union is fatally flawed because it leaves each member state to set its own fiscal policy. There are good reasons for that, but it is not sustainable indefinitely. The Eurozone must get either much more centralized or fall apart. All the Rube Goldberg contraptions the ECB and others invent are temporary fixes. They’ve worked so far. They won’t work forever.

I still think the most probable scenario is that Germany and the Netherlands (and the rest of the northern European cabal) reluctantly agree to let the European Central Bank mutualize all the sovereign debt, taking onto their balance sheet and issuing new ECB-backed debt for the entire zone. There would have to be serious constraints on running deficits after that point, but it would prevent a breakup, or at least delay it for another decade or so.

Of course, within a few years those new deficit constraints would be ignored. I said in a previous letter Germany will need to collect almost 80% of GDP in 30 years in order to be able to deliver its promised healthcare and pensions. Their inability to do that will be evident much sooner. Germany will end up becoming one of the biggest problems.The next installment, Debt clock ticking, was a bit philosophical. I talked about debt letting you bring the future into the present, buying things you couldn’t afford if you had to pay for them now. But the entire world went into debt for the equivalent of tropical vacations and, having now enjoyed them, realizes it must pay the bill. The resources to do so do not yet exist. So, in the time-honored tradition of lenders everywhere, we extend and pretend. But with our ability to pretend almost gone, we’re heading to the Great Reset.

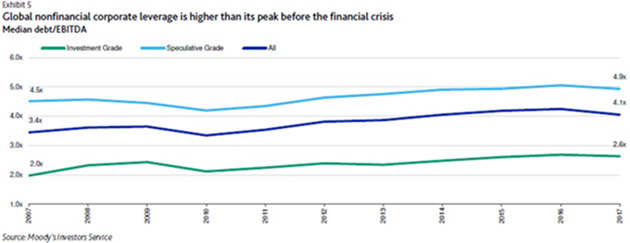

Source: Moody’s Investor’s Service

Then I reviewed some of the McKinsey and IIF numbers and described the amount of leverage that’s built up in the system. Just a decade after the Great Recession, the average non-financial business went from 3.4x leverage to 4.1x. They are now roughly 20% more leveraged than they were the last time all hell broke loose. CEOs and boards seem to have learned little from the experience—or maybe learned too much. If you believe the Fed has your back, then leveraging to the moon makes sense.

Pension Problems

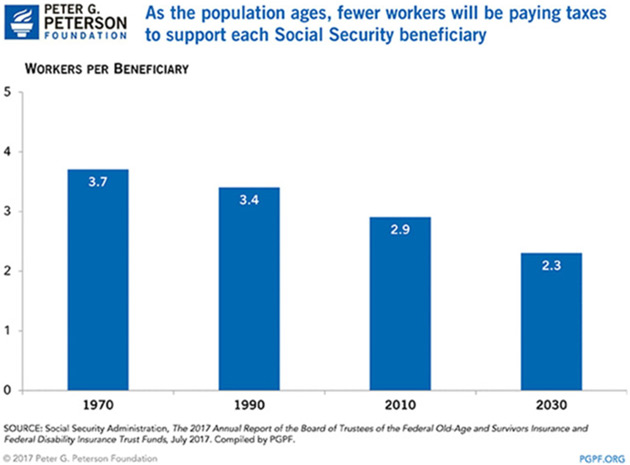

The last three letters in the series got personal for many readers as I talked about pension debt. In The Pension Train Has No Seat Belts, we looked at the demographic challenge facing US pension funds, mainly state and local government plans but also some private ones. We are asking a shrinking group of working-age people to support a growing number of retirees and that’s just not going to work.

Source: Peter G. Peterson Foundation

The promises employers made to workers are a kind of debt. They’re the borrowers, workers are the lenders… and unlike in 2008, this time it will be lenders who get hurt the most. A new report by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) shows the unfunded liabilities of state and local pension plans jumped $433 billion in the last year to more than $6 trillion. That is nearly $50,000 for every household in America.

Nor is this only a US problem, as we saw in Europe Has Train Wrecks, Too. According to the World Economic Forum, the United Kingdom alone has a $4-trillion retirement savings shortfall that will rise to $33 trillion by 2050. This in a country whose entire GDP is only about $2.6 trillion and doesn’t account for the increasingly likely disaster Brexit will be. Switzerland, Spain, and others have similarly dire outlooks, often driven by even worse demographics than we have in the US. Germany, as noted above, is simply off the rails.

Finally, in Unfunded Promises, we reached the ultimate debt problem: US government unfunded liabilities. On paper, Washington’s debt is about $21.2 trillion… but that doesn’t include the $13.2-trillion unfunded, off-the-books Social Security liability, or the $37-trillion Medicare unfunded liability. Those aren’t my numbers, by the way; they come from the Social Security and Medicare trustees and are probably understated. My friend, Boston University professor Larry Kotlikoff, thinks it should be more like $210 trillion. He has a considerable amount of published works and a book he co-authored with fellow Texan Scott Burns.

That’s not all. The federal government also has liabilities for civil service and military pensions, veteran benefits, some defaulted private pensions via PBGC, and open-ended guarantees to entities like FDIC, Fannie Mae, and more.

The budget outlook is horrible even without all that, too. The Congressional Budget Office thinks federal debt will be 200% of GDP by 2048, and that by 2041 it will take all federal tax revenue just to support Social Security, the various health care programs and pay interest. That’s before defense or anything else the government does. And that’s assuming relatively high growth and NO recessions and a rising stock market forever as we ride off into the sunset.I wrapped up quoting my friend Dr. Woody Brock, who thinks the most likely outcome will be wealth taxes at federal, state, and local levels. I truly hope he’s wrong about that, but I fear he is not. My preferred new tax for the US would be a VAT that eliminates the Social Security tax (thus giving lower-income workers and businesses a raise) but still funds Social Security and healthcare. Other government expenditures would be funded from income taxes which could be reduced significantly, and even eliminated on incomes below $50,000. Now that’s a tax cut that would boost the economy and balance the budget.

There really are only two ways to solve this problem: massive taxes on someone, or a debt liquidation of some kind. And remember, if you are getting a retirement pension fund and/or healthcare, your benefits are part of that “debt liquidation.” Both will be painful. We have pulled forward our spending and must eventually pay for it. The time is coming. Please don’t shoot the messenger.

Let’s summarize. Global debt is over $225 trillion. By the beginning of the next decade it could be over $300 trillion. Global government unfunded liabilities are easily in the $100-trillion range today and could easily double by the end of the next decade. Debt service, pensions, and healthcare will take 20-25% of GDP in many countries (more in some of Europe).

Your mileage may and will vary by country. In some, there will be inflation and in others, deflation. We will be thinking the unthinkable and choosing policies that seem insane to even mention today. But then, think about what Japan is doing. And the ECB. Add in automation and the loss of hundreds of millions of jobs in the OECD countries. Then think about what will happen in the emerging economies.

But at the same time, imagine all the new companies being built and fortunes made. The opportunities. The situation, as Doug Casey once quipped, “Is hopeless, but not serious.” Not yet. Not for you and me.

Next week we’ll discuss what you can do.

*This is an article from Thoughts from the Frontline, John Mauldin's free weekly investment and economic newsletter. This article first appeared here and is used by interest.co.nz with permission.

- Credit-Driven Train Crash (May 11)

- Train Crash Preview (May 18)

- High Yield Train Wreck (May 25)

- The Italian Trigger (June 1)

- Debt Clock Ticking (June 8)

- The Pension Train Has No Seat Belts (June 15)

- Europe Has Train Wrecks, Too (June 22)

- Unfunded promises (June 29)

73 Comments

We are certainly witnessing a "Johnny's last harrah" stage of this credit cycle. We live in the age of great smugness and complacency. What's coming will affect everyone to some degree. Those who lose least are today's insightful "DGM's", a label easily conjured up by the complacent fool. Soon, debt will begin to rise in value as premium asset prices fall. By the time the asset rich/cash shy realise what's happening, it will already be too late to exit positions they no longer cherish.

The great reset is certainly coming. This is the price paid for kicking the can for three decades.

The world is awash with debt and CB's are producing heaps more of it every day simply by turning the handle on the printing press. And RP thinks his term deposits which are simply debt owed by a bank to him are going to increase in value?! How valuable will his TD's be when the bank his flogging them off in it's closing down sale?

This is just an excuse. In such times, cash is king.

So where is the safe place for wealth to hid RP ?

Very good question! Cash assets, TD’s & expect trading banks to weather the storm?

Yes absolutely. Place it in this cash fund. Kiwi Wealth spread it amongst all major trading banks as term deposits. Under any OBR, less loss as the risk is spread. Personally, apart from this, I have a TD with Rabobank. Under a grandparented arrangement ended in mid 2015, the principle and all interest earned is fully guaranteed by the parent bank in the Netherlands. Of course you could always open up TD's with various banks yourself! If you think the returns are pathetic then considering the risks before us, more fool you!

I can't see any asset class being sparred, all will be affected. Due to it's extreme overshoot, ppty will decline the most.

As for cash, well the Aus banks have the govt guarantee, not so NZ.

My own approach is to get rid of debt - as you can bet your assets will decline, but your debts certainly won't.

You Might want to check that Rabobank guarantee. My understanding was that when it ended it ended. i.e. they do not cover anything now.

Nothing will make it safe from inflation, if there is a debt problem the government will almost certainly print money. Sometimes I wonder if you are better off having debt which will probably be written off somehow...

Agree..If it all goes pear shaped cash may have a small window, with which to buy distressed hard assets that generate revenue but ultimately will be destroyed. Until then diverse holdings in food and essential services are probably best and keep digging that fallout shelter!

Now that's smug :D

Does anyone know - can New Zealanders who are non residents of Australia set up bank accounts there? Or are only residents of Australia allowed to set up bank accounts?

Not totally impossible I believe, but not easy either.

https://www.finder.com.au/foreigners-open-a-bank-account-in-australia

" If you reside in another country and don’t intend to migrate to Australia, you’ll need to speak to a local bank who has international ties with a bank in Australia. "

Clever Chinese have also been purchasing farms, wherever they have been allowed to do so!

The "clever Chinese"? According to the McKinsey report and visualization referenced in the Maudlin post, one of the key take-outs is "China’s total debt has quadrupled over the last decade, a rise of $32 trillion, fueled by debt of the nonfinancial corporate sector."

What if the those farms have been purchased on financial resources that are little more than a fiction?

Ah but will Chinese banks foreclose on something that is feeding them? Fictitious or otherwise the debt has bought the most important commodity in a major crisis.

'Rub a dub dub, thank God for the grub.'

Came across a new term on the weekend

Awfulizing is a term coined by psychologist Albert Ellis. It refers to an irrational and dramatic thought pattern, characterized by the tendency to overestimate the potential seriousness or negative consequences of events, situations, or perceived threats.

.... could apply to much which is written here.

Note that Retired-Poppy's agenda for a long time has been to promote a crash - rather than to promote stability. (Go read a selection of his posts here over the past 12 months.)

Some contributors here have surmised that he yearns for a large fall in house prices, so that he can personally benefit from purchasing a property at a much discounted price. That may, in fact, be true. (But he wouldn't be the only person here in that category.)

In any case, readers would be well advised to exercise caution with everything that Retired-Poppy says.

TTP

Hogwash. You just made it easier to get across my point by presenting yourself as a perfect specimen. Right after words "complacent fool"

TTP with the greatest of respect to RP’s prowess do not believe that he anymore than you or I are able to profoundly influence and precipitate market crashes simply by posting opinion on this good web site and forum. Let’s all just remain robust and good hearted and respect the freedom of being able to have an opinion and express it here, right or wrong.

Foxglove, well said!

Society needs more Floxgloves!

Thanks but not really. Don’t overlook that I am on the noxious weeds list.

Hi Foxglove,

I have no problem with freedom of expression.

But it pays to know a person’s biases/ prejudices........ Otherwise, one can be misled/deceived.

Why be gullible, when it can be easily enough avoided?

TTP

TTP

You comment as though the GFC never happened

How long can you keep your head in the sand, this debt crisis is going to blow up and it is not a matter of if, its not even a matter of when, its a matter of how soon!

Enjoy the good times while you can, we are all in for a lot of pain, like it or not!

Some highly leveraged property investors in Auckland are comforted by the fact that during the GFC, property prices in Auckland on average fell no more than 10%. They are using this as their expectation of a worst case scenario.

Their analysis is similar to this recent review of historical prices in Australia - https://propertyupdate-com-au.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/propertyupdate.com…

Correct question is "where is the safe place for wealth CLAIMS.."

The numbers only represent a claim over something. If the something isnt there, there is no safe place.

And all claims are a claim over the futures ability to generate an energy surplus.

The catch is we have been using debt to mask the lack of energy surplus ....

Not good.

See Orlovs 5 stages of collapse

http://cluborlov.blogspot.com/p/the-five-stages-of-collapse.html

"where is the safe place for wealth CLAIMS.."

Military might.

Why else is the USA flexing it's muscles? Way too much debt to ever repay.

Exactly - They have used debt to fund an armed force that can stop anyone claiming that very debt.

Call it what you want - immoral, unethical, wrong, but in terms of ongoing survival it is pure genius

Any other nations that have done that and increased the size of their military quite dramatically since 2000?

Entirely so. That is how to enforce new rules and make sure you get (more than) your share of the shrinking pie.

“Government is the Entertainment division of the military-industrial complex.” ― Frank Zappa

"We will be thinking the unthinkable and choosing policies that seem insane to even mention today."

I would agree with this statement. But cant see how this can translate to opportunities... basically the rules coming are unknown

Any working system (in whatever form) is designed to exploit available resources. Our current one is based around debt. So as financial manipulation eventually causes debt to fall over (and faith in debt to fall over), the rules change.

Be liquid have cash or can convert to cash easily

Minimize debt

Be diversified. Never more then 20% in one asset class.

Hold Gold as a currency of last resort 5-10%

Don't bet against the USD . To bet on a economic collapse would be to bet against the USD. I do not subscribe to this notion and would argue further strengthening against other currencies. We are in a USD bull market for the next 5-10 years.

I am also at a loss as to how to mitigate the effects of the big global financial meltdown .

I was given some advice by an old Stockbroker in his 60's about 7 years ago on trip to London :-

1) Reduce personal debt to zero

2) Dont invest in anything that will be under-water if interest rates revert to their 25 year ( one generation) average ( and that's about 8 to 10% ) unless you can feed the shortfall.

3) Dont invest in anything in which you dont understand exactly how it makes its money ( such as Bitcoin )

4) Buy only stocks in Companies which have a strong balance sheet ( low debt ) and TANGIBLE assets like property , harbours , airports , pipelines , and forget anything with an inflated goodwill on its balance sheet ..... like Myspace ( anyone remember them ) or Boo.com or Wang or Compaq

5) dont invest in stuff that is likely to be disrupted by technology like Nokia and Apple or Palm or Blackberry or Xero , or Polaroid or Kodak , because someone is going to make something better for less cost , and the Palm is a classic ( who even remembers the Palm pilot all the rage 20 years ago ).

6) Stick to investing in stuff Humans will ALWAYS need such as food , Water , and electricity , the yields may be pedestrian , but there is always a mouth to feed , or a meal to be cooked.

7) And most importantly , watch your investments closely , dont ignore them and hope -for - the - best , things change rapidly and a good share can become a dog overnight

Boatman, good post and think ditto. Equities nowadays are though risky even for the so called blue chips. Think Fletcher Challenge. And worse Telecom where only a matter of days after the august Cullen had been bemoaning NZr’s obsession with property investment at the expense of the sharemarket, his protegee Cunliffe triggered the collapse of that share price. So who can tell what is a solid share investment?

1) Reduce personal debt to zero.

(Actually only required where you know that the person calling in the debt can and will overpower you)

2) Invest in yourself and your family: Health, shelter, water supply, food, energy, education, and defense.

3) "Invest" in everything/anything else with the assumption that it will "lose" at some point.

(You can invest in all the Food, housing, etc.. for everyone else - but how much is your "investment" worth if China, USA, or anyone else, takes it by force?)

Oh dear, you've gone all doomsday prepper on us.

Doomsday isn't just Zombies, Aliens, and Hollywood catastrophes.

Yeah, it pretty much is really. Maybe I just have a bit more faith in my fellow NZers, I think for NZ to get to a walking dead like dystopian future would pretty much require an alien landing or somesuch nonsense. AFAIK from what i've read we managed to survive the great depression without roaming gangs of looters and murderers.

Pragmatist, I spotted Noncents out and about:

'but how much is your "investment" worth if China, USA, or anyone else, takes it by force?'...

Well I would say that we can eliminate the 'or anyone else'..... and it's not really the USA's thing to invade and occupy forever, if they had had that ambition they would have done it 50 years ago... So that leaves us with mmh.

West Germany, Japan, South Korea, Okinawa........Just sayin'.

Oh, and Iraq. You watch.

very sage advice boatman

Boatman,

I don't often agree with you,but here,I would go along with much of your post.

I have no debt and my assets are;60% equities focused on sustainable dividends-20% rental property-15% cash-3% bonds and 2% miscellaneous assets. i have more than doubled my cash over the past 2 years as I have become increasingly cautious over ever higher equity valuations.

This is good advice!

I am also at a loss as to how to mitigate the effects of the big global financial meltdown .

I was given some advice by an old Stockbroker in his 60's about 7 years ago on trip to London :-

1) Reduce personal debt to zero

2) Dont invest in anything that will be under-water if interest rates revert to their 25 year ( one generation) average ( and that's about 8 to 10% ) unless you can feed the shortfall.

3) Dont invest in anything in which you dont understand exactly how it makes its money ( such as Bitcoin )

4) Buy only stocks in Companies which have a strong balance sheet ( low debt ) and TANGIBLE assets like property , harbours , airports , pipelines , and forget anything with an inflated goodwill on its balance sheet ..... like Myspace ( anyone remember them ) or Boo.com or Wang or Compaq

5) dont invest in stuff that is likely to be disrupted by technology like Nokia and Apple or Palm or Blackberry or Xero , or Polaroid or Kodak , because someone is going to make something better for less cost , and the Palm is a classic ( who even remembers the Palm pilot all the rage 20 years ago ).

6) Stick to investing in stuff Humans will ALWAYS need such as food , Water , and electricity , the yields may be pedestrian , but there is always a mouth to feed , or a meal to be cooked.

7) And most importantly , watch your investments closely , dont ignore them and hope -for - the - best , things change rapidly and a good share can become a dog overnight

The central banks have a couple of crazy cards up their sleeves whether they will work who knows (1) Negative interest rates (2) Direct Cash to peoples banks accounts either via a Govt Scheme or similar. The direct cash could be constructed along the lines that 50% - 100% must be used to pay back debt if you have any. The next major crash is likely to be a very abrupt event so any central bank action may not have any effect.

If there are any lessons to be learnt from the Cyprus default the Banks have the power to take money out of all accounts to save themselves and my understanding is the banking regulations are the same here. All accounts over a certain amount had a hair cut so Cash is great but also not completely safe. Shares the same, property the same but if you are freehold then a drop doesn't matter. Any big crash affects all asset classes and people and of course the rise in unemployment and confidence that a recession or depression can bring hurts everyone

Cash in bank is actually very insecure because it is so easy for govt's to steal, or otherwise diminish in value (printing money) giving them exactly the liquidity they need at the stroke of a pen. In doing so they screw only a few generally moderately wealthy (or cautious cashed-up economically aware) people. No matter how unjust that is attractive to a politician, see Cyprus.

Loathe as I am to say it the best option is mortgage-free properties. Mostly inflation proof, little if any depreciation, and with majority of country owning houses will never be singled out by politicians (who also tend to own several rentals each) to pay for their economic mis-management.

Shoreman, if we are suggesting a Cypris type event is possible then, what's the point of having OBR? To me, saying there's the risk of us catching Cypris disease is like saying a future Government will raid all our Kiwisavers in times of greater need - um nope. Isn't OBR designed to keep the bank operating on Monday, after coming under State Management on Friday, protecting borrowers and depositors alike? I'd suggest any decision for a % of haircut is only taken by statutory managers once the extent of the victim banks difficulties is known and not before.

I'd suggest that apart from a mortgage free dwelling, having cash spread amongst all major banks. Reduce the risk of all ones savings being hit under an OBR event. It would be incredibly dire if all NZ banks ended up under OBR. Who the hell is predicting that?

In the event of RBNZ money printing, surely our small country's currency would sink big time, sending inflation soaring along with interest rates. That said, what would happen to mortgage repayments/property values then? Interest paid on bank deposits would surely remain elevated too - right?

That reminds me of the Wizard of ID. Thus quoth the King to his peasants. “ I have good news and bad news. First the bad news. I am going to nationalise the kingdom’s superannuants fund. And the good news. You are all going to be allowed to work until you are eighty.”

NZ govt will absolutely raid kiwisaver if they are really in deep financial poo. Just like pension funds have been raided all over the world by corporates, unions, and governments who could get away with it (generally in dire circumstances, but not always). That is why it is a dangerous investment over the long term. Things are fine now, but 20 years down the track, when the government is no longer able to fund all the welfare requirements or the economy has tanked and there is this lovely big pile of cash they could skim from you would be a fool to bet against it. Has happened recently in Argentina, and to a far smaller degree in Ireland a few years back during their Financial crisis.

This is exactly why kiwisaver is structured as it is, the money is not held by the govt, or the kiwisaver provider. Its no easier for the govt to raid kiwisaver than it is for them to just raid your bank account directly.

Those other funds were raided by their custodians.. Govt held pension funds raided by govts, Union pensions raided by unions.

The right wingers are donning their tinfoil hats en-masse today.

...this draconian view was born from the days when National (Muldoon) raided the country's National Provident Fund.

In 2007, I tried to convince my Sister, this can never be repeated under Kiwisaver. They have only just retired now, still with a mortgage and no Kiwisaver.

Kiwisaver is safe as from being raided. Its the quality of investments within it that matters. This aside, if a future Government raided the NZ Cullen Fund, it would not surprise me.

Having a mortgage on retirement is not great. Given the official age is 65 you only have a limited number of years while your mobility is still good to do all the things you enjoy.

Muldoon did a lot of damage, but the lack of faith in Government is also common within asian culture. Trying to get people to save and invest is an uphill battle when people don't trust to the Government to not do something wrong.

RP - Kiwisaver is all investments in the likes of stocks, no?

What guarantee is there that that system survives?

None whatever.

Good luck believing in an ever-increasing bet on an ever-bigger future.

RP - Kiwisaver is all investments in the likes of stocks, no?

What guarantee is there that that system survives?

None whatever.

Good luck believing in an ever-increasing bet on an ever-bigger future.

powerdownkiwi, not true. There are other options. Choose cash funds in very shaky times or as recommended when very close to retirement (two years). Presently, I'm with Kiwi Wealth. Their cash fund is spread amongst all major banks and a few highest quality corporates. I think its the only cash fund that spreads out like this. The return is not great after fees but as you can see, it's never gone negative; https://www.kiwiwealth.co.nz/home

I differentiate between cash and banks. The former will be king for a while after a crash, the latter are a collection of digital '1's and '0's in computers, limited liability, no guarantee, and in a world where many central interest-rates are zero and some nudging under that?

For a few brief decades, there was enough surplus energy and few enough people, for forward bets to be underwritten. I don't see that continuing.

powerdownkiwi, I view GFC2 as longer and much deeper, in particular for AU, NZ, China and Canada. I see hope for an eventual slow recovery out the other side with hard lessons learnt, supportive policies in place. Like you say, interest rate stimulus buffers have all but gone. I can see property being out of vogue for decades under the weight of Boomers constant deleveraging/cashing out and much tighter lending criteria. Expectations for quick gains will disappear under the weight of bad experiences.

You can buy NZ Government treasury bills - the next question is - who is the legal owner of the securities? i.e are the securities registered in your own name or in the street name (typically your securities broker) in a cash account?

If they are in your own name, then that should be safe.

If they are in the street name, then you are potentially a unsecured creditor, and need to check the credit risk of the securities broker (I'm assuming that there is no investor guarantee). Not sure if the broker needs to have separation of accounts of client assets with the broker's own assets.

If you have a margin account with a broker, then the securities will be in the street name.

CN, there are always KiwiBonds, registered in individuals name. Government security reflected in the relatively low rate of return.

R-P,

I have been increasing my cash over the past couple of years and have used some of it to buy Kiwibonds. The low rate of return doesn't bother me at all. I would unlikely to do this,if NZ had Deposit Insurance laike almost every other country.

Be careful of that option in a financial downturn. It really depends on the securities and investments that the cash fund owns. If you recall, that was how the Reserve Fund in the US broke the buck - it was chasing yield and the fund owned a lot of short term securities issued by Lehman Brothers.

https://www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/09/money-market-reserve…

In a financial downturn, the safest option for Kiwisaver is to buy a Kiwisaver fund which is unleveraged and only owns short duration NZ government bonds.

CN, the Kiwi Wealth Fund is totally transparent. They invest the funds only in term deposits at six different NZ banks. The % allocated together with $$ are clearly shown. I am not aware of a Kiwisaver cash fund that invests in Government Bonds. I'm open to stand corrected on this.

The govt can nationalise kiwisaver if they have sufficient votes in the house - eg if they have a big enough pool of welfare recipients (like Venezeula managed to do in just a few years of stupidity, creating a voting block to ensure that socialism destroyed their economy), it is a big pool of money they could grab quickly.

Govt can't easily take ownership of millions of distributed assets spread around the planet by 100's of thousands of individuals. eg a property you own in the US, or a rental property in the UK or some shares in an offshore bourse. 20 years ago Argentina was in reasonable shape, but they have just Nationalised their pension fund.

It's your call if you want to put faith in the NZ govt of 30 years time given the obvious financial squeeze coming from AI/automation, ageing demographics and the seeming dawn of an era of more protectionist international trade that will damage NZ. I think losing access/control of your money for 20-30 years is a mugs game in this environment.

Yeah, and if they want to they can nationalise your house too, just declare all land property of the state with a few strokes of the pen. Or anything else they choose to. But doing either would be political suicide, which is why its not going to happen while we have any sort of democracy.

And nationalising all property in a future with high unemployment due to automation/AI etc would make more sense.. Lots of unemployed people who will have to be living somewhere, an increasingly small pool of landlords holding all the property.. Hmmm, need houses for people, can't afford to keep paying accommodation supplements.. just take the houses from the owner and give them to the tenants for free. No actual changes, except to tell the tenants they no longer need to pay rent to the landlord, and that the state will no long be paying them (some) of their benefit.

I think if a big crash did occur that you seem to angle at often there is no safe place for cash, if a Government/country defaults nothing is off the table, all bank accounts, kiwisaver, cullen fund they are all prey. The cyprus situation was the country defaulting, same thing happened in Iceland, I will always have a % in cash but relative to everything else property may go down in value (mortgage free) but you will still have the property to live in or rent. Spread the risk maybe. I would trust NO Government in times of crisis.

The issue in Iceland was that the banks were reliant upon wholesale financing. When the banks were unable to refinance maturing wholesale financing due to the global credit crunch, then the banks had liquidity issues.

The Icelandic bank recapitalisation was a unique situation and debtholders encountered losses. Onshore depositors did not lose out, to my knowledge. It was the offshore depositors (particularly UK depositors in Icelandic banks) who were at risk.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2008%E2%80%932011_Icelandic_financial_cri…

In the recapitalisation of the banks in Cyprus by depositors taking haircuts, one point to highlight was that quite a few of the large depositors were foreigners (I don't know if they were part of the resident voting constituency in Cyprus). In particular Russians, who were parking their money in Cypriot banks to keep the cash outside of Russia. So if the government can take money without losing any political capital of the resident voting constituency, that certainly seems like an easy solution.

Another point to note was that the majority of assets owned by Cypriot banks that lost value (and hence eroded loss absorbing capital at the banks) were not household mortgages or commercial lending, but actually government bonds. Now how can government bonds lose value? Well, they were bonds of the government of Greece which defaulted.

When the crash does arrive i might be able to pick up a cheap 2nd hand Ford Ranger.

I think he’s right about the eventual introduction of wealth taxes. It’s possible that they can cover all asset classes.

Just print more money and everything will be fine

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.