Rather go to bed without dinner than to rise in debt.

—Benjamin Franklin

What can be added to the happiness of a man who is in health, out of debt, and has a clear conscience?

—Adam Smith

There are no shortcuts when it comes to getting out of debt.

—Dave Ramsey

Modern slaves are not in chains, they are in debt.

—Anonymous

Debt isn’t always a form of slavery, but those old sayings didn’t come from nowhere. You can find hundreds of quotes on the Internet discussing the problems of debt. Debt traps borrowers, lenders, and innocent bystanders, too. If debt were a drug, we would demand it be outlawed.

The advantage of debt is it lets you bring the future into the present, buying things you couldn’t afford if you had to pay full price now. This can be good or bad, depending on what you buy. Going into debt for education that will raise your income, or for factory equipment that will increase your output, can be positive. Debt for a tropical vacation, probably not.

And that’s our core economic problem. The entire world went into debt for the equivalent of tropical vacations and, having now enjoyed them, realizes it must pay the bill. The resources to do so do not yet exist. So, in the time-honored tradition of lenders everywhere, we extend and pretend. But with our ability to pretend almost gone, we’re heading to the Great Reset.

I’ve been analogizing our fate to a train wreck you know is coming but are powerless to stop. You look away because watching the disaster hurts, but it happens anyway. That’s where we are, like it or not.

And we don’t even really like to talk about it in polite circles. In a private email conversation this week, which must remain anonymous, this pithy line jumped out at me:

The total of Federal (remember they do not use GAAP) debt, state debt, and city debt [unfunded liabilities included] exceeds $200 trillion dollars. There is no set of math that works to pay this off. Let me be sure it’s heard by repeating it: There is no set of math that works to pay this off. Therefore, there has to be some form of remediation. This conversation is uncomfortable, so it is avoided.

Today’s letter is chapter 5 in my Train Crash series. If you’re just joining us, here are links to help you catch up.

Last week, we discussed the Italian political crisis and potential eurozone breakdown. That is a dangerous possibility, but far from the only one. As we’ll see today, the world has so much debt that the cracks could happen anywhere.I said above that if debt were a drug, we would outlaw it. But we also know that people get hooked on illegal drugs all the time. The law doesn’t stop them. Likewise, common sense and regulations don’t stop us from overusing debt. And as we will see, the withdrawal can be painful indeed.

Too Many Trillions

Three years ago, the McKinsey Global Institute released a massive research report called Debt and (not much) Deleveraging. It reviewed the global debt situation and where it might be taking us. The answers were not pleasant. I wrote about it at the time in Living in a Free-Lunch World.

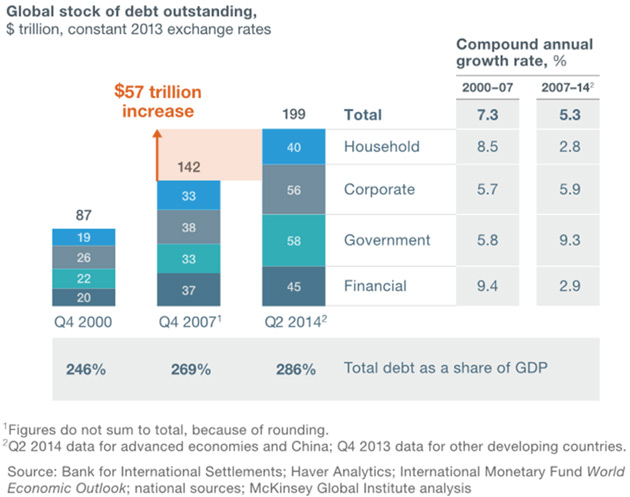

The McKinsey team created this fascinating graphic summing up the world debt situation as of mid-2014.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

From the Great Recession’s beginning through Q2 2014, global debt grew $57 trillion to $199T. (From here on, I will use capital T to denote trillions, since we must use the word distressingly often). That includes household, corporate, government, and financial debt. It does not include unfunded liabilities.

Dr. Woody Brock wrote this week:

CBO projections show that within 18 years, entitlements spending will absorb all US federal tax revenues—leaving no revenues even for interest expense on the debt and for the military. In Germany, which proudly pays annually for its expenditures without incurring debt, Deutsche Bank has estimated that by 2045, income tax rates of 80% (total, not marginal rates) would be needed for its PAYGO system. The entire workforce of the nation would be in bondage to the elderly. Other nations face even worse prospects.

I should note that the CBO projections assume no recessions and an optimistic compound 3% growth rate. I think most of my readers would assume that neither will end up being the case.But even $199T back in 2014 was a lot of money. We should also note that, through the magic of double-entry accounting, each dollar of debt liability appears on someone else’s balance sheet as a $1 asset. Debt is wealth, if you are the lender. Most of you reading this probably are, in some fashion.

(If we could somehow make this debt magically disappear, we would also make wealth disappear, but we may have to do exactly that. This is a serious problem we will address later in this series. For now, just note that I am aware of it.)

McKinsey calculated that from 2007–2014, world debt levels grew at a 5.3% compound annual growth rate. That was slower than the previous seven years but still considerably faster than the world economy grew. Hence, debt as a share of world GDP rose to 286%.

Not all the debt categories grew equally. Government debt grew far faster than household, corporate, or financial debt. Household debt growth fell to a relative crawl, from 8.5% annual growth in 2000–2007 to only 2.8% in 2007–2014. Which makes sense because families had little choice but to deleverage, often via bankruptcy.

Government and corporate borrowers faced no such pressure. Their debt kept growing at a slightly higher pace after the recession. Yes, some corporations hunkered down and rebuilt their balance sheets. Most did not. They kept borrowing and lenders kept lending, encouraged by central bank-generated liquidity.

This is an important point I’ll return to in future letters. We talk a lot about profligate governments running up debt, and rightly so, but they are not alone. Businesses are equally and sometimes more addicted to debt. That would be fine and even positive if it were funding innovation and new production. But much of this new corporate debt paid instead for share buybacks that reduce equity, leaving the corporation more leveraged. That seems to be what shareholders want. They should beware what they wish for.

Rapid Maturity

As far as I know, McKinsey has not updated that 2015 report, but we can get similar data from the Institute for International Finance’s Global Debt Monitor.

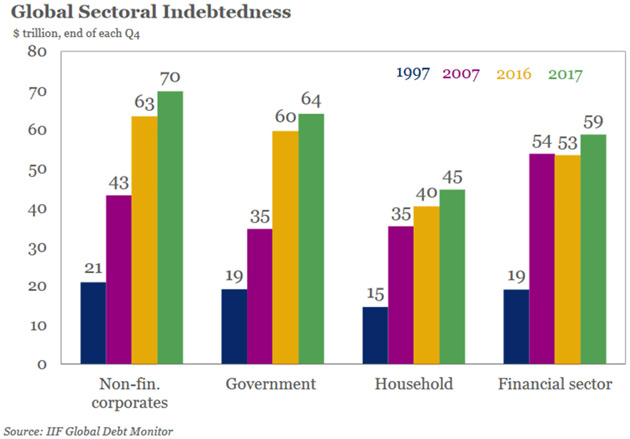

The totals aren’t the same as McKinsey showed for those years, so I suspect they have different data sources. They’re close enough for our purposes, though.Adding together the same-colored bars, we get these global debt totals:

- 1997: $74T

- 2007: $167T

- 2016: $216T

- 2017: $238T

If those are accurate and my math is right, global debt grew at an 8.5% compound rate from 1997 to 2007. Then it slowed to 3.6% from 2007 through 2017. That’s good. We went on a worldwide debt diet.

But last year, we appear to have binged because debt grew 10.2% from 2016 to 2017. Breaking it down by sector, non-financial corporate debt grew 11.1%, government debt grew 6.7%, household debt grew 12.5%, and financial sector debt grew 11.3%, all in calendar 2017.

Looking only at 2017, government debt seems to be the least of our problems. The biggest debt growth was everywhere else. But why did it suddenly accelerate last year? In part, because the world economy grew enough to let global debt-to-GDP ratios fall slightly.

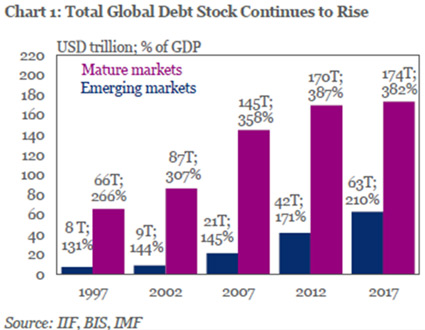

Here’s another IIF chart showing global debt as a percentage of GDP for both “mature” (what they call developed countries) and emerging markets:

The developed world is far more leveraged than the EM world, but EM countries are no pikers at 210%. They often lack the stabilizing resources developed countries possess, too. IIF points to Argentina, Nigeria, Turkey, and China for the largest debt ratio increases last year. But many emerging market businesses and financial companies borrowed money in dollars, as the dollar was relatively weak and US interest rates ridiculously low. Further, our yield-hungry investors, both as individuals and its institutions, were more than willing to lend to them to get something more than 1–2% that they could from sovereign bonds.

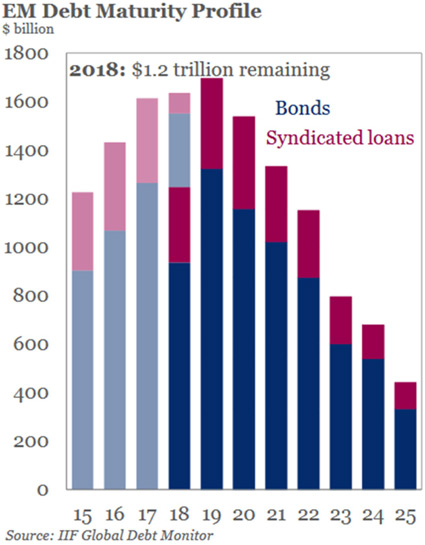

This level of emerging market debt is unsustainable because, among other reasons, debt matures and must be either repaid or refinanced. Here’s emerging market debt by maturity:

Some $4.8T in emerging market debt matures from this year through 2020, much of which will need to be rolled over at generally higher rates and, if USD strength continues, in a disadvantageous currency environment. Will that be possible? I don’t know, but we’re going to find out—possibly the hard way.But that’s a relatively minor concern. We have a much bigger one back home.

Leverage Plus Leverage

The IIF report includes this note about US corporate debt:

US non-financial corporate debt hit a post-crisis high of 72% of GDP: At around $14.5 trillion in 2017, non-financial corporate sector debt was $810 billion higher than it was a year ago, with 60% of the rise stemming from new bank loan creation. At present, bond financing accounts for 43% of outstanding debt with an average maturity of 15 years vs. the average maturity of 2.1 years for US business loans. This implies roughly around $3.8 trillion of loan repayment per year. Against this backdrop, rising interest rates will add pressure on corporates with large refinancing needs.

I see at least three alarming points in this paragraph.

First, corporate debt is now 72% of GDP. That’s in addition to the government debt that is approaching (or has passed depending on how you count debt) 100% of GDP and household debt at 77% of GDP. Add in 81% financial sector debt, and the US combined debt-to-GDP ratio is near 330%.

Second, 60% of new corporate debt is coming not from bond sales but new bank loans—and those bank loans have much shorter maturity, averaging 2.1 years. That means refinancing time is coming for much of it, and rates are not going lower.

Third, IIF infers about $3.8T in corporate loan repayments each year—just in the US. That’s a lot of cash companies need to find and I’m not sure all can do it. Aside from higher interest rates, the companies that need credit (as opposed to high-rated ones that borrow only because they can do it cheaply) tend to be riskier.

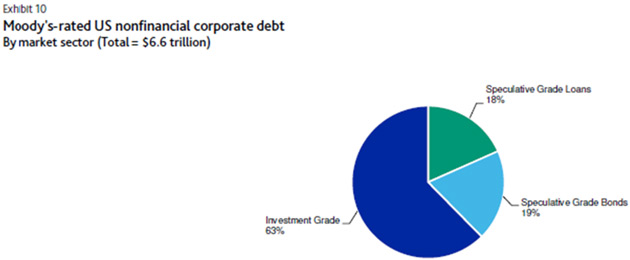

From a recent Moody’s report, we see that 37% of US nonfinancial corporate debt is below investment grade. That’s about $2.4T.

Source: Moody's Investors Services

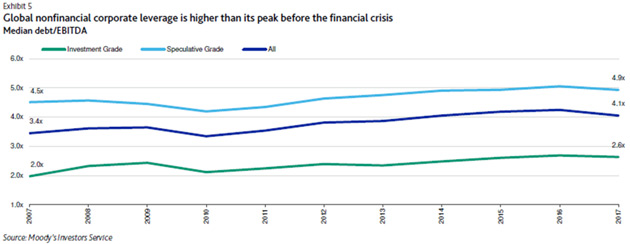

The proportion is similar globally. Furthermore, all corporations, both investment grade and speculative, added significantly more leverage since the Great Recession.

Again, not all leverage is the same. Some companies borrowed to fund share buybacks but have vast cash flow and reserves. They can easily deleverage if necessary. Smaller, riskier companies have no such choice. I think they present the greatest systemic risk.

That said, it’s still a bit mind-boggling that, even after the Great Recession, just a decade later the average non-financial business went from 3.4x leverage to 4.1x. They are now roughly 20% more leveraged than they were the last time all hell broke loose. CEOs and boards seem to have learned little from the experience—or maybe learned too much. If you believe the Fed has your back, then leveraging to the moon makes sense.

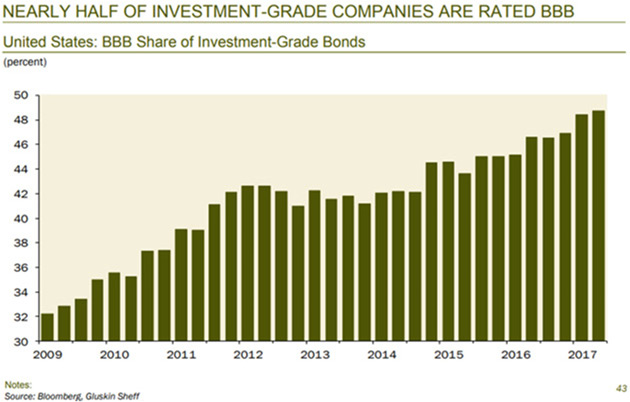

Now, I know some readers will take comfort in the fact that 63% of the corporate debt is rated investment grade. But as they say in Texas, hold on, cowboy, don’t ride away so fast. A lot of that debt is rated BBB, the lowest investment grade rating. For the glass half-empty crowd, that means they are just one step above junk. The chart below from my friend Rosie (David Rosenberg) shows that the number of BBB-rated companies is up 50% since 2009.

Source: David Rosenberg

The problem, as I described in High Yield Train Wreck, is that bondholders and lenders won’t wait for the rescuers. When funds and ETFs, which hold BBB debt, start getting redemptions, investors won’t hang around to see which domino falls next. Institutions have rules that will make them start selling troubled bonds early. Liquidity probably won’t be there. Clearing the market will require sharply lower prices, which will create more selling pressure and eventually recession.

To further exacerbate the problem, the rating agencies that didn’t react quick enough in 2008 may be a little bit more trigger-happy this time. This will cause heartburn for CEOs with BBB paper outstanding.

To be sure, regulators and Congress took measures to avoid a similar crisis repeating. The banks aren’t the problem. The “shadow banking system” is the source for much of the shaky debt. The same investors stretching for yield in emerging markets have loaded up on private debt, too.

Steve Wasserman’s last weekly commentary is a good capstone here:

Moody’s has issued a statement that CMBS loans are now almost as risky as in 2007 because 75% of them are interest only, and the interest only period is now 6 years, up from 2.2 years just a few years ago. In addition, they are becoming much more covenant light, and are at higher leverage. All of this is a red flag since these things create much more risk of serious problems when the recession hits. There is also a bigger concentration of single tenant properties, which, as we have seen in retail, can be deadly in a recession. Asset and sponsor quality is also deteriorating. There is now so much competition to put out loans by so many non-bank sources, that borrowers can get lenders to compete, which always means lower quality underwriting. Far too much capital chasing too few good deals.

Underwriting is not nearly as bad as in 2006–2007 yet, but it appears the trend is what it always has been, when the economy is strong and there is too much capital, underwriting standards fall down, and then the stage is set for a bad outcome when the economy goes bad. It is typically 10–12 years between collapse of the last crash and then credit quality deterioration and the next credit collapse. We are at 10 years. Dodd Frank had rules to try to avoid a replay of 2008 in CMBS, but a lot of loans now are made by private equity funds that are not subject to these regulations.

One thing that is immutable is that as each generation comes into Wall Street, they think they know better how to do it, and they eventually do the same dumb loans in pursuit of profits and bonuses. It has never been different. We are not about to have a major crash again, but CMBS loan quality is deteriorating now, and one day in the next 2–3 years, it will be a bad problem. When they start doing a lot of CDOs and virtual CMBS pools with derivatives, then that is a sure sign the end is near.

I think Steve pretty much has it right. We’re ok for now, but we will have a problem when recession strikes. The next crisis, which I think will be yet another debt crisis, won’t look like the last one, but it will rhyme.

Circling VulturesAs in nature, carnage for some is opportunity for others. Investment bankers who specialize in corporate liquidations and restructuring see good times coming. Here’s a haunting quote from last month:

"I do think we're all feeling like we were back in 2007," Bill Derrough, the co-head of recapitalization and restructuring at Moelis & Co., told Business Insider. "There was sort of a smell in the air; there were some crazy deals getting done. You just knew it was a matter of time."

A matter of time, indeed. Moelis and others are confident enough to start staffing up before the business appears, despite the tight labor market. Think about how unusual this is. Most companies are in a just-in-time, fully-optimized production mode. You succeed by precisely matching production capacity with current sales… unless you are a restructuring specialist. In that case, you hire the best people you can find and let them twiddle their thumbs until opportunities appear. And you think they will, soon.

Others will have opportunity as well—even you, if you are holding cash and in position to buy some of the valuable assets that will get “restructured” in the next few years. Doing it successfully will take extensive research and iron discipline. Many will try, few will do it well. Start preparing now and you may be one of the few.

Remember, in 2009, it was easy to find great companies paying 4% to 6% dividends with single digit P/E ratios. You didn’t have to be an accredited investor to pick up juicy returns. You will get another chance not too many years from now. Patience, grasshopper.

------------------------------------------

*This is an article from Thoughts from the Frontline, John Mauldin's free weekly investment and economic newsletter. This article first appeared here and is used by interest.co.nz with permission.

- Credit-Driven Train Crash (May 11)

- Train Crash Preview (May 18)

- High Yield Train Wreck (May 25)

- The Italian Trigger (June 1)

37 Comments

It spells trouble when both Government and non financial corporate debt has exploded. Reduced tax revenue along with deepening fiscal limitations will greatly affect how today's more inwardly focussed Governments respond in the next crisis. It's scary to imagine the potential loss in employment after automation has yet another go. Whats worth noting is that it was interest rates at levels witnessed many centuries ago that just simply posponed a tragedy; https://www.marketwatch.com/story/seven-centuries-of-interest-rates-and…

Dismiss these articles as DGM propaganda at your own financial peril. This is the real deal.

R-P... thks for the link. The original article it refers to is worth reading.

There are some issues here I see,

a) Greenspan is in-arguably for me one of the significant contributors to our present state due to his in-competence and dogma. Here the senile old ***** is just drooling again IMHO.

b) Everyone assumes when they look back historically we can grow for ever, ie this is cyclic. I'd suggest with Peak oil (and all the other peaks like iron, gold, coal etc) the cost of extraction / availability will be too high for our present industrial society/economy to ever really grow again and that is if we are lucky, hence no rebound / cycle. Far more likely is that we will enter decades if not more of economic contraction as our world de-globalises as we adjust to living local and within whatever renewable energy we have available.

c) Given b) then the present mountain of debt can never be repaid there will never be the energy and hence economic activity to ever re-pay it. So a financial crash is inevitable, the only Q is when.

Population peak will be the mutha of all peaks.

Good quotes and very true IMHO. Debt is easy to get into and we are constantly assaulted to get into [more] of it and way harder to get out of.

Amen Steven...Ain't that the truth..

Debt seems to be ubiquitous and most believe it to be harmless.. in this age of consumerism.

Its a kind of invisible form of slavery,... in a way.

It is the modern slavery IMHO.

Why do I work? to pay my bills. What is the impact on the cost of debt of this? I have seen some writings that suggest the cost of goods is inflated by 30% just to cover the debt incurred along the supply chain. This means then in effect the owners of capital cream off the equivalent in Govn tax for no benefit to society unlike PAYE.

and then throw in the inflated cost of accommodation. Just looking at what my house would cost to rent, about $2200 per month that if I did not own it outright would be a financially crippling sum if I had to pay that.

In a small economy, large input and outflows must be questioned.

Ask yourself this...will they come clean, or just wash their hands of any responsibility for their share of the pile.

Who is the architect of it all.

Once again this may show just how unjust we have all become, cos it ain't all about Houses, it is all about how easy cross border money laundering has become for those in need, in this nanosecond age....

(And they need it more than ever, cos it is building)

http://www.architectmagazine.com/design/editorial/dirty-money-shiny-arc…

Who exactly would you have question capital flows? The govt? Given that they are the source of most of the problems in the first place I wouldn't think that's a good idea. The EU is thinking along the same lines as you and will likely ban short selling of the euro, bonds, etc. That's all very well, but just remember that you will be taking out most of the market makers and then you'll have NO bid. Result? Collapsing currency, collapsing bond market, collapsing economy. By targeting money laundering, you'd achieve little and tank the economy at the same time.

While your point may be valid, the difference isn't the outcome but when it happens.

Thank you John Mauldin, very convincing alas. Now, if all that debt cannot be paid maybe we can start thinking about which debt should not be paid. Now that debt is mostly tradeable, the market provides a clue.

My target of first choice would be debt now held by vulture funds. Where they have bought debt at cents on the dollar their enforceable right to collect should be written down to that number of cents (plus some modest interest perhaps). To put it another way the sanctity of contract will certainly be broken by widespread default so there might be better/worse ways of breaking it. Some laws might need to change, in New York state?

Debt might be less-eagerly-traded after such a change and future lender behaviour might improve.

Others may suggest other targets? It is a target-rich environment.

The way excess debt has been and always will be repaid is through debasing the currency.

It’s called inflation!

Hasn’t gone away - just out of sight for a period.

Great for debt holders - just don’t be a saver unless your in hard assets - eg Housing.

Maybe those with a long memory have it right after all.

so where's the inflation?

What I cannot understand is... where is the currency devaluation? Everybody seem to be debasing or creating money like madmen and the value is the same?

Well how about , you show me the growth first?

Vulture funds are small fry. The biggest targets by far would be govts. They have borrowed endlessly for the last 50yrs and have NO PLAN to EVER repay the debt. The reality is that they won't be able to service the interest in the not-too-distant future, let alone the principle. If you or I conducted ourselves in this manner then we would have been bankrupted long ago and/or jailed for accounting fraud. However, because they supposedly represent the people, this is ok. We deserve what's coming to us, pure and simple...

There are four key classifications of borrowers:

1) government debt (at the national level)

2) regional government debt (local city council debt)

3) corporate debt (financial and non financial corporates)

4) household debt

The current area of vulnerability for New Zealand is total household debt where levels are high when taking household debt collectively for all households in New Zealand. Given that the main source of borrowings for households are the banks and non banks and that the household debt exposure is large relative to bank capital levels, then the capital adequacy of the the banking system is potentially vulnerable to a large level of loan losses. The key asset that has been used as collateral for household debt is residential real estate, so the market prices of residential real estate is key for the stability of the banking system.

If the banking system has a large level of loan losses then financial stability of the banking system could be a concern. Look at the impact of the banks needing to be recapitalised in Ireland in 2008/ 2009, the US in 2008 / 2009, and in Cyprus in 2013, and its affect on the local economy afterwards. When the banks are capital constrained, credit overall becomes difficult to come by as banks tighten loan underwriting criteria as the banks are in self preservation mode. This is when credit lines get pulled, and borrowers are forced into a financially constrained position and urgently need liquidity. Given that most household borrowers do not have access to sufficient liquidity, households then begin to sell assets to raise liquidity. To reduce their debt, deleverage and raise liquidity, many highly leveraged households sell their only asset - residential real estate.

Let's get the basics right and hold off the scare mongering for a second.

Some of us think of debt and borrowing as a hard cash out of mum and dad saving account and has to be returned by next year otherwise M&D might be in trouble or live in vain ....it's not like that!

Debt is created and expanded so that the lender makes his money out of interest on that loan.

It is neither logical nor beneficial for any lender to lower the lending amount or to ask for it back (as long as the interest is paid) .. in both cases the lenders ( who invested a fortune in selling the loan in the first place) will lose money !! .... so who will kill the golden goose ? ... No one will as long as the borrowers stays within the boundary of reasonable risk profile and can pay !!

In fact all sorts of, business, political, economic and "other" maneuvering is usually done to increase a country's debt amount ...

The lender(s) have no issue with money that is printed out of thin air and legitimized as real lending money ... these are only numbers on a hard disk somewhere, but they generate income that is being recycled again to borrowers ...

So why would anyone want to kill this business?.... On the other hand, debt is a weapon, a sword on the borrowers neck to tow the line and be Good !!

Look, I think that despite the crocodile tears of the IMF and the world bank and others about the huge amounts of debt in the world etc, everyone is continuing the same path of lending more and encouraging states and individuals to borrow more as long as they are producing more and paying interest on time .... The US is borrowing over $1.5 trillion dollars every year and literally wasting it - I think they have or will soon top $22T ... are they going to pay it back?

Smart people borrow and invest the money to generate few folds of the amount of interest they pay on it .. and they have assets and insurances etc in cover losses and emergency situations - the lenders know that and are happy with a win-win ... they are also happy for people to borrow to buy an asset as long as they service the debt and pay ontime.

The only folks in trouble will be the ones who borrow and waste with no assets to cover - these are the idiots who would be exposed when the tide goes down !!

Eco Bird, I started reading your comment and all the World's debt troubles momentarily disappeared. Only because I was laughing my head off :) Your take illustrates why we have a debt driven ponzi in the first place. It also clearly explains why all Kings in their Castles think they're impervious to what's coming next.

I doubt that you understood a word I said RP, that is why you were laughing ... but good to learn that you are happy with your TD ticking over nicely.

As you know, when (if) the whole boat sinks, No one is impervious ... my point was that do not expect that to happen soon as it is counter intuitive and in no one's interest.

you can hate it and call it what you like - but it is what it is !

The fundamental difference between us is that you keep saying the sky will fall soon, next , tomorrow etc... while we keep making money and laugh all the way to the bank in anticipation !

Eco Bird, I'll admit we do share one thing in common. Both our investments are ticking. Only mine is in a good way.

Eco bird lives in a world where the banks, acting with benevolent self interest, only ever loan money to borrowers who are certain to repay it. Would never, willingly or unwilling, increase the cost or credit or tighten the terms on which it is offered. Would never require a borrower to make a prepayment to restore an LVR (“it’s ok, take your time, and just pay us back when you can”). I think eco bird lives in a Heineken ad

Read a lot from people like you in 2007, they sounded like they knew the financial system like the back of their hand.. and then by year end they had their heads covered in sand...

A lot of similar points being made in Auckland currently by the Auckland property price bulls and bears.

Haha yes I’ve seen that one before. They really can’t stand each other. “Fundamentals are strong”, “economy has been transformed”, bla bla

Eco bird - the problem ultimately with your reasoning is this line

"The only folks in trouble will be the ones who borrow and waste with no assets to cover.."

Its INCOMES that are in (collective) trouble. Hence the need to continually debase currency and run deficit spending under the guise of ïnvestment" ... all to prop up demand and provide income.

But capitalism died in 08 and it aint coming back. When SHTF, the deflationary spiral means everyones incomes go down the tube (in slum lord speak that means if the tenants dont have an income, its hard to collect rent)

So, basically you’re just saying that debt is simply money that pays interest...until it doesn’t.

Money is created out of debt, so there is money floating around somewhere to pay MOST of this debt? The problem with paying off debt and quantitative tightening is it's a contraction of the money supply. Obviously when debt is repaid, the money supply shrinks. This is probably the cause of many recessions.

The cracks are likely to be the loss of confidence in major currencies and therefore countries refusing to buy their bonds. Kings of old did debt jubilees until the Roman Empire did away with that kind of thinking. Good article, I like the quotes. I have one you could add:

Many a conqueror has become wealthy by stiffing his creditors.

~Zack Brando~

All will be well until we have an " Event " old chap as Anthony Eden reminded us precipitates a crisis.

It will occur - but almost by definition we don't know where or when. Think CHCH earthquake on a world scale. Yellowstone blows and covers Chicago with a metre of ash as has happened previously.

Major asteroid strike - we have had 5 pass undetected between us and the moon year to date - a hair's breath in astronomical terms.

Meanwhile being human we all just carry on and enjoy life as we should.

John, thanks for your article. You highlight the issues of massive overbearing well. I’m not as much of a fan of debt as EB, but you could emphasise the reasons for interest rise are almost always a source of new growth that gains momentum, and not just a recovery of levels of activity.

Innovation is the only long term source of business growth, and we are in innovative times, so the issue is not so much debt as being caught on the wrong side of innovation. You look at overgeared individuals, businesses or countries in depth, and what starts of looking like a debt problem almost always turns out to be poor investment selection. Conversely, the “too much debt so well stop spending and pay some off” has limited success - look at Greece.

If our collective innovation was so impressive, there wouldnt be the need for such massive bond buying by the central banks. There would be GROWTH! Instead

The “too much debt so well stop spending and pay some off” has limited success ... BECAUSE we are now in a consuming debt phase only. This isnt innovation or investment, its a ponzi scheme.

Our primary source of ALL wealth is what comes out of the ground. All wealth/money/debt is only ever a claim on this. Thats the hard limit we are facing.

Our primary source of wealth certainly DOES NOT come out of the ground. If that were the case then Russia, Africa, etc would be wealthy and Germany, Japan and Switzerland would be poor. The wealth of a nation is the productivity of its people. A bunch of lazy bums sitting on top of gold/oil reserves are still lazy bums without wealth.

Ludwig - "The wealth of a nation is the productivity of its people"

LOL. Yes neolib 101. You must wonder why the US bothers with that whole military thing they have going....

Either way the issue is the world economy as a whole, but you will find Russia is indeed in a better position when the debt ponzi collapses.

Japan & Switzerland have plenty of tertiary wealth (paper claims over 1) only as long as the ponzi holds.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119200918.ch9

What Is Wealth?: (Hint: It's Not Money)

Once it comes crashing down it will take 20 years for us to recover to a period of zero growth.

I wonder if I will see another period of prosperity within my lifetime.

Whilst we should enjoy our day in the sun we should all be preparing for the upcoming crash, none will be immune.

Part of the problem is that governments have a total debt addiction - & not just for themselves, but to keep the broader economy goosed along.

All developed countries have tax regimes that reward debt and penalise savings. NZ could arguably be the worst, in that debt payments are tax-deductible, and the resulting benefits in growth are usually tax-exempt.

worth watching on the credit bubble

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hJpC3bmzZU

One article by John Adams - https://www.news.com.au/finance/economy/australian-economy/how-to-prepa…

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.