My still-unfolding Train Wreck series is getting a lot of attention. It’s not exactly good news, but people at least appreciate the warnings. Thanks to all who sent thought-provoking comments. I always consider them carefully.

A few readers characterized the crisis I foresee as being a repeat of the 2008 fiasco. That’s partly right, in the sense we will have a painful economic and market downturn, but the causes will be quite different.

Last time around, the root problem was excessive residential real estate debt. Reckless lenders made unwise loans so unqualified borrowers could buy overpriced homes. These loans morphed into securities and derivatives and all blew up. I don’t think it will happen that way again. The next crisis will spring from corporate debt, equally imprudent but structurally different.

This train wreck will be similar in one respect, though. The first defaults will occur at the lowest end of the problematic market: high yield or “junk” bonds. They will play a role comparable to subprime mortgages in the last crisis. We’ll see mortgage problems as well, but I think overleveraged companies will be the core problem.

Before we go into that, you might want to review prior installments in this series or read them first if you’re just now joining us.

Today, we’ll look at a not-so-prime example of the reckless investments people are making in high-yield bonds, then consider how big the problem can get.

But we’ll start with a little history.

What Are They Selling?

Older readers will remember a Houston-based company called Enron that blew itself, its employees, and investors to smithereens during the 2001–2002 recession. Investigations followed. Some management (properly) went to prison.

In the late 1990s, Enron engaged former Reagan speechwriter and Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan to help explain itself to the world. Noonan, possibly the greatest business writer of her generation, couldn’t do it. She described the experience in a 2002 column.

Let me tell you what I saw when I was there. I saw cavernous rooms with big monitors on the walls and on desks too. The monitors and computers were blinking out numbers. I remember the numbers and words on the screens as bright green. Young future Masters of the Universe were standing with phones, monitoring the numbers, saying things, buying and selling. I met with a woman famous in the company for being in charge of putting big natural gas pipelines into Central or South America and India. She seemed intense and intelligent and, like the men, very Armani but kind of Texas Armani—everyone well-tailored but with more gold, more colors than Wall Street people, who are sort of more gray-hued…

And I thought, they spend a lot of money. That was one thing that hit me hard in Houston: They were “hemorrhaging money!” as Tom Wolfe’s Sherman McCoy said. They were building this and tearing down that, they were, they told me, talking to legislators in various state houses, lobbying to get deregulation bills passed. All of it seemed expensive, labor-intensive, time-intensive.

And it all seemed so tentative, so provisional. The Enron building was huge; the Enron sign outside, the big tilted E, was huge; the gold earrings on the women executives were huge; the watches on the men were huge; the paychecks were huge; the company’s ambitions were huge. But all of it seemed to depend on things that were provisional. If they are able to build the big pipeline in India, it will be great and profitable—provided it happens. If they are able to get states to deregulate electricity, and Enron is able to provide it, and it all goes well, it will be great and profitable—if it happens. If the Central or South American pipeline goes through and works and runs a profit it will be great—if it happens. An empire built on ifs. It all seemed so provisional…

I went away for a few weeks and worked hard and tried to put together a speech and make a contribution to the annual report, but none of it really worked… the key part was that I couldn’t help them explain their mission because I didn’t fully understand what their mission was. I understand what the Kenneth Cole shoe company does. It makes shoes and sells them in stores. Firestone makes tires. I couldn’t figure out how Enron was making its money, what exactly it was selling, and every time I asked, I got a kind of gobbledygook answer or a cryptic one, like “The future!”

Sound familiar? That’s probably how you or I would feel if we toured some Silicon Valley unicorns today. They’re very confident and have big dreams. Whether the dreams can ever make money is a different question.

Enron wasn’t entirely vaporware. Those people Peggy Noonan saw really did trade electricity. Before the collapse, it spun off a subsidiary called Enron Oil & Gas which survives today as EOG Resources, a major shale player. But most of the dreams went nowhere, disguised by accounting fictions that eventually fell apart.

This is all obvious now. Back then, it wasn’t. Intelligent, seasoned investors believed Enron really was “the future!” and gave it their hard-earned money not only for equity but for debt. Lots of debt. Enron's bankruptcy filings showed $13.1 billion in debt for the parent company and an additional $18.1 billion for affiliates. But that doesn't include at least $20 billion more estimated to exist off the balance sheet.

Now other investors are buying into today’s dreams. Maybe some will end more happily than Enron did. But you might not want to bet your own financial future on it.

Office Space

I’ve talked about potential problems in the high-yield bond market. That’s the polite name for “junk” bonds, issued by companies that can’t earn an investment-grade rating even from our famously lenient bond rating agencies.

This is a two-layer threat. First, many of these companies are so marginal that even a mild economic downturn could render them unable to make bond payments. The second layer is that bondholders will want to sell those bonds, but the liquidity they presume probably won’t be there.

I could point to many examples, but we’ll take one that was in the news recently: WeWork. The still-private company issued bonds last month, giving the public a peek into the books. The offering raised $702 million at 7.875%—a nice yield if it lasts the full seven-year term. That is if you get your capital back at the end of those years. I’m not convinced investors will.

WeWork, at least, has a clear business model, one proven by other companies, and they are executing with panache and flair. It signs long-term leases for office space, then subleases to the hordes of freelancers and independent contractors who need an inexpensive workspace. Much of it is just tabletop space in open suites. This is apparently attractive to the younger set who like being close to peers, and the price is certainly right. WeWork provides all sorts of amenities which create an enjoyable workplace. Founder Adam Neumann is a charismatic executive who’s obviously adept at raising capital. So, it could last for some time.

The risk is that WeWork’s renters could disappear quickly if their own income dries up, as will happen for many when the economy breaks. Investors seem to believe this risk isn’t just manageable, but negligible.

Grant Williams featured a lengthy WeWork analysis in this month’s Things That Make You Go Hmmm... article. After walking through the numbers and comparing WeWork’s current $20 billion valuation with comparable companies, Grant says investors have essentially gone insane.

The list of investors’ concerns around WeWork belong to a bygone era when those lending a company their precious capital (and foregoing a risk-free return) used to require that company’s assets and liabilities bear some relationship to each other.

Negative cashflow also used to be ‘a thing’ and ‘strategic challenges’ once raised an eyebrow or two.

Not anymore.

Instead, in a world of yield-seeking and minimal due diligence, the combination of a (relatively) juicy yield and the appearance on a company’s register of superstar names like Masayoshi Son is all that’s required for what once counted as material aspects of a company’s business to be forgotten.

Grant isn’t the only skeptic, either. Developer John McNellis ran the numbers and reached this conclusion:

If, instead of merely subleasing 14 million feet, WeWork owned 14 million feet of office buildings at a valuation of say $500 a foot, the company would be worth $7 billion or roughly one-third of its self-touted value. And that $7 billion valuation would presuppose owning all of those buildings free and clear of debt.

McNellis also highlights something important from the bond disclosures.

WeWork neither signs nor guarantees its own leases; rather, for each lease it signs, it creates a single purpose entity [SPE] with very limited capitalization; i.e. its leases carry almost no financial exposure to the parent company. These entities are known as SPE’s (“Screwing Probably Expected”).

So, if WeWork’s renters disappear, the first victims will not be WeWork, but the property owners who leased space to WeWork. They may have little recourse. But they’re probably leveraged themselves, so the losses will flow upstream, eventually to the banking system. And we know where that ends.

Unraveling Dream

Here’s the truly scary part: WeWork isn’t unusual. The landscape is littered with similarly tenuous corporate borrowers. It is the inevitable consequence of a free-cash decade. Here’s Grant Williams again.

Ten years into the ongoing laboratory experiment being conducted by the world’s central banks, everywhere you look there are multiple examples of the kind of lunacy those policies have fomented by reducing the cost of capital to virtually zero and forcing investors to take risks they would ordinarily avoid in order to find some kind of return.

WeWork is one example of a company for whom, in the face of rapid growth, massive negative cashflows aren’t a problem, but there are plenty of others. Uber, AirBnB, SnapChat and, of course, Tesla have all captured the imagination of investors thanks to lofty dreams, articulated by charismatic CEOs—but the day things turn around and the economy begins to weaken or, God forbid, investors seek a return on their investment as opposed to settling for rolling promises of gigantic, game changing revenues to come, it is over.

Look, I’m all about “lofty dreams.” I have them myself. I admire entrepreneurs who take risks and break new ground. They are the key to economic growth. Building a business is the single best and most effective way to create personal wealth. But it’s also true that most of those dreams are simply dreams and will never come true. A few who bet on them win big, but most lose some or all of their investment.

Adam Neumann at WeWork has convinced investors that his office space rental company should actually be viewed as a technology company. We are creating a “community” he says. Whatever that is. There is a successful and larger competitor whose valuation is roughly 10% of WeWork. But then, they are in the office space rental business, not the “creating a community/building the future” business.

A long line of businessmen and women seemingly have the gift to convince investors to buy unrated paper that is unsecured with no assets behind it. The problem is that unraveling dreams tend to be contagious. Investor psychology is fragile, so the collapse of one high-profile dream can bring lesser-known ones down, too. I think we’re approaching that point.

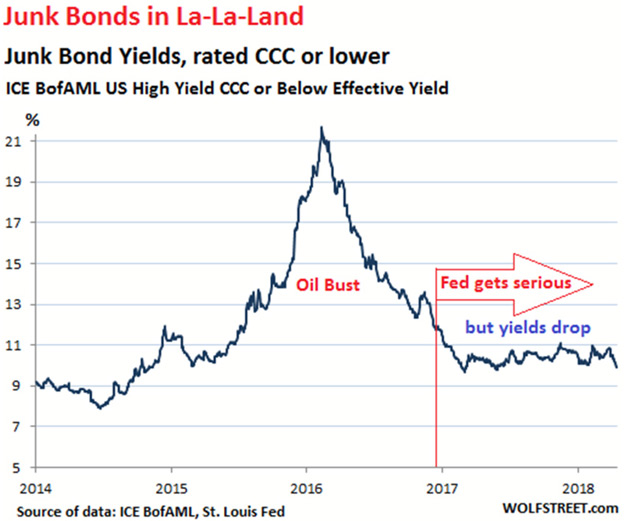

Yet something interesting and a little counterintuitive is happening. You might think the yield on bonds issued by risky companies would rise as the cycle matures. That would be consistent with investors demanding more compensation for their risk. But it hasn’t happened that way.

Source: Wolfstreet.com

After spiking higher during the 2015–2016 oil bust, when many shale drillers had serious problems, yields dropped in 2017. Not by coincidence, that’s also when the Federal Reserve began hiking rates every quarter. Fearing capital losses, Treasury investors relaxed their credit standards and created more demand for junk bonds, which sent those yields lower. That’s my theory, at least.

We’re seeing classic end-of-cycle behavior: throw caution to the wind and plunge capital into the market’s riskiest corners. This artificially-induced buying is propping up companies that would otherwise succumb to the fundamental forces arrayed against them.

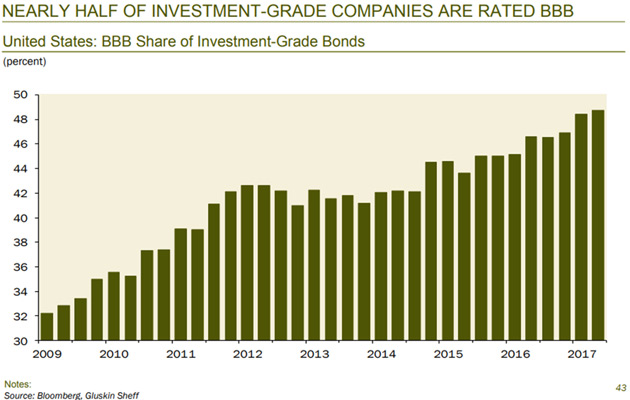

Nor is it simply a junk-bond problem; the investment-grade corporate market is becoming measurably riskier. Here’s a Dave Rosenberg chart that my friend Steve Blumenthal shared recently.

Source: On My Radar

Almost half of investment-grade companies are rated BBB, just one step above junk, up from just one-third in 2009. When the economy breaks, some of those companies will run into trouble. Some of those will get downgraded, which will force many funds to sell them, thereby intensifying the liquidity storm I’ve described.

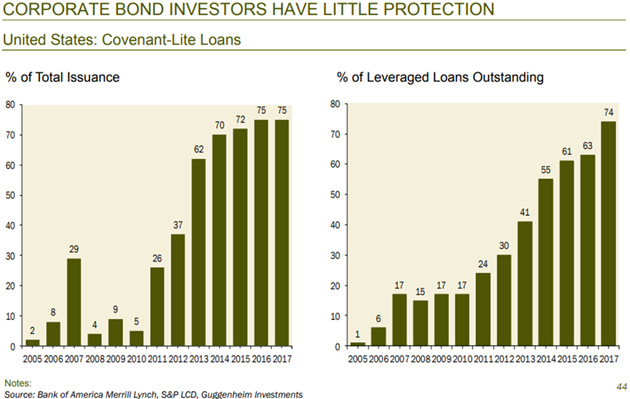

A few companies will probably default. Bondholders may have little recourse to recover their principal, having accepted covenant-lite conditions and taken on leverage themselves.

Source: On My Radar

Leveraged lenders will be in a pickle when the defaults begin, but they won’t be the only ones. It all flows downstream. Whoever extended credit to leveraged loan buyers will be in trouble, too. That’s how problems in one market spread to others.

Covenant Lite

Let’s explore what we mean by the term covenant lite. Borrowers can become extraordinarily creative.

Covenant-lite loans is a type of financing that is granted with limited restrictions. Traditional loans generally have protective covenants built into the contract that protect the lender, including financial maintenance tests that measure the debt-service capabilities of the borrower. The issuance of covenant-lite loans means that debt is being issued to borrowers with less restrictions on collateral, payment terms, and level of income. Covenant-lite loans place less restrictions on the borrower in terms of requiring collateral and a certain level of income. Covenant-lite loans are also referred to as cov-lite loans. (Investopedia)

Some covenant-lite loans let the borrower repay with freshly issued debt—in essence, printing their own money. Others allow them to borrow even more money, perhaps pledging assets that should have gone to the company, in order to let the firm’s initial private equity investors pull out equity. This effectively transfers additional risk to bondholders.

The closest comparison I can imagine is the dot-com run up to 2000, and the debt is still growing. While high-yield bond issuance dropped somewhat over the last few years, leveraged loans at the same companies are up 12% since 2014.

There is a lot of overlap in the companies that issue high-yield bonds and issue debt (loans), and it is no coincidence that the rapid increase in leveraged loans has coincided with a period of decline for high-yield debt. Since the end of 2014, the US high-yield market has shrunk by 3.7% while the loan market has grown by 12.7%.

In aggregate, the combined size of the US loan and high-yield bond markets has been broadly stable since 2014 (chart 2). Again, this is very different to the wave of mega-leveraged buyouts (LBOs), which expanded the high-yield and loan markets in the 2005–2007 period.

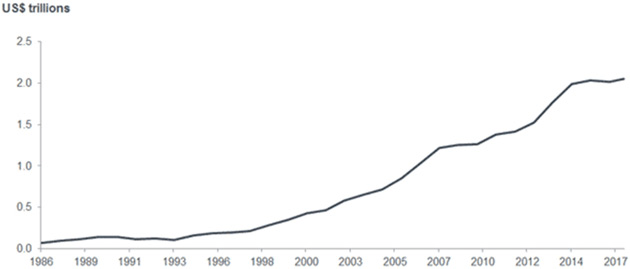

Chart 2: combined size of US high yield and loan markets

Source: BofA Merrill Lynch, Janus Henderson Investors, as at September 30, 2017

My data sources show different amounts of high-yield bond issuance, but all show a lot of it. Looking at just the Morningstar high-yield category, I see $1.4 trillion in mutual funds and almost $650 billion in high-yield ETFs. Some of these funds are well-managed and some are so large they buy anything (maybe including WeWork) because they need to invest their incoming cash.

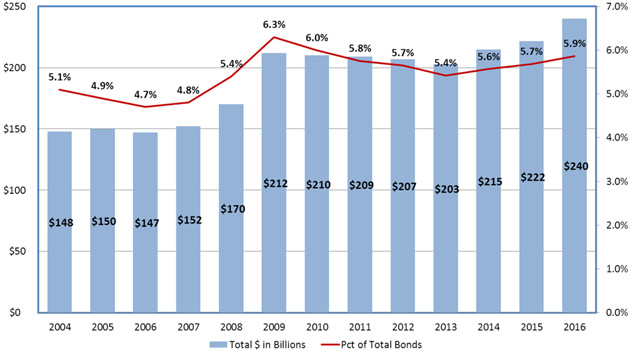

Those numbers don’t count high-yield bonds held outside of funds and ETFs. As this National Association of Insurance Commissioners chart shows, the insurance industry has $240 billion worth of high-yield debt which represents 5.9% of their total bond investments.

Source: National Association of Insurance Commissioners

Then there are pensions, foundations, and endowments that have their own exposure to high-yield bonds.

The difference is (this is a big generality) institutional investors are typically buying specific bonds, so they don’t quite get the exposure to some of the extreme jumps. Further, they can hold to maturity, making liquidity less of an issue.

The roughly $2 trillion in high-yield bond funds and ETFs get marked-to-market every day. This means individual investors can see their values go down as well as up. If losses make enough of them begin to withdraw, it will force those funds to sell into a shrinking market, putting further pressure on valuations.

In a plunging market, you don’t sell what you want, you sell what you can. Funds have to meet redemptions. That means increasingly lower-rated bonds remain for investors who don’t move early. Valuations drop and it just cascades.

A decade ago, we saw a subprime mortgage debt crisis bleed into the rest of the markets. I think this time, the high-yield debt crisis will have the same result. Next week, we will look at The Second Act. Later on, we’ll get to emerging market debt and perhaps even worse, the non-corporate grade bond market in Europe—and don’t get me started on the problems in China.

This is a long story and we’re still at the beginning.

------------------------------------------

*This is an article from Thoughts from the Frontline, John Mauldin's free weekly investment and economic newsletter. This article first appeared here and is used by interest.co.nz with permission.

27 Comments

WeWork, some never have to. Work is now a four letter word. I swear.

They borrow, someone else does the work.

WeWorkers take their spoils early, the same as spoiled leveraged and over leveraged people, who think it can never happen to them.

When Work stops, when Sales stop, because all are borrowed to the hilt, then Profits stop and Work declines.

Work used to mean a modicum of success, and perhaps save a little cash... for a rainy day at a Bank. now it is two people's endeavors to build houses to show how successful they are, In NZ...with Fiat Money, borrowed from a bank.

There is no incentive to "Save".

An "Investment" is something you dream about, Facebook is another App description of an all Play, no Work Investment. It depends on Adverts. People spending up large. Flogging off your details...to others....

Billions invested, thousands employed. Hope the Power does not go out. But I pray it does....the thieving bar-stewards.

Same with Internet. WW3 would be won by a simple strike, even if they thought it would 'Work" being broad minded....on the Internet.

I used to work in Business Continuance and Recovery.

I gave up when Management could not see the "Would" for the trees. They never gave a thought to Power Outages. Trump is a problem, so is Putin, So are many, many people who cannot see their Futures.

Oil, Gas, Coal, Gold, no matter what Future you see. All depends on Electricity, Buying, Selling, in Nano-seconds. Short Selling, etc.....Debt....don't own it, don't see it...cannot touch it.

Worth mega bucks. If ya believe in USA dollars and Trillion Dollar debt Mark.ettes....and Pipelines between 'Friends with benefits"...with Oil.

Trillions owed..all around the World. Power to the people....nah...the Machines and Computers have it all under control.....

Hope the batteries.....last..eh..Eion.....or Profits may never occur, in our lifetime.

An "APP" is being designed as suicide is rising in New Zealand.

Most people, particularly the Young, cannot see their "Futures" beyond a phone...That they carry to control their World.

More been invested in a House....a phone, than real work.

They even take yer Munny, if ya don't use it. and keep it up..........Go figure.

Gotta go...Sun is shining.....

I have already had the discussion this morning about all the old buggers on here (and be clear I am an "X") look down on the young and talk condescendingly. They should try putting themselves in the young persons shoes and look up for a change. Or better still talk to the young about the view they see. Their behaviour only reflects their view.

Scarfie I might be old but I share your pain for the young

You may not know it but in the 1980s mortgage rates were 23%

People were leaving NZ for Australia in droves

Now people have flooded into NZ which is a good thing because NZ had an aging population at the bottom of the world previously.

The future is indeed what you dream and make it yourself. Sometimes it takes people 30 yrs to learn this while others learn it pretty early in life.

Why not learn SWIFT the Apple software you can learn for free online and go start creating your own APPs Start looking to the world not merely living in your current paradigm

Expand your mind & horizons

If your mind is one of the 20% that has slight mental illness of any description seek the necessary solutions Do not allow yourself to wallow & remain depressed. Good Luck Scarfie us old folks do understand more than you know

Its just one giant Pyramid scheme! As long as we can sell it to another fool......

Have we learned nothing!

This "train wreck" series is very insightful and scary at the same time.

I'm still wondering how long this will go on for. There are US companies with P/E ratios of up to 300. Many companies will be set to fail either due to not being a real business or refining their debts will drive losses, or if they can't refinance they will go bankrupt.

There's a lot of money and not a lot of real businesses to pair with the money so the prices are heavily inflated. The debt market is over inflated with junk.

When the CLOs fail and the everyday investors lose confidence making them empty their 401K there will be blood in the streets.

Dictator

The question is why are we waiting so long for GFC2 ?

Every man & his dog knows the worlds debt is exponentially higher than it ever was before the last GFC

Robert Prechter has been preaching this longer than anyone I have his 2010 book

Please anyone buying gold or silver make sure you hold the asset for real not paper or an entry on a computer

I’m sure governments will go after any and all forms of wealth to keep themselves in power so even your gold & silver will probably have to be surrendered like the haircut your savings accounts will take

Expect your rates or property taxation to climb to very high rates

Like I said to Scarfie seek help if you are depressed now early

You’ll need your medication

"The chief executive of the Property Institute says Auckland's median house price could double by 2026-2027."

It is far more probable that they will be 50% less in value within a decade.

... Bernard Hickey now says that house prices across Orc Land will rise 50 % over the next 5 years ...

As , they've risen 50 % or more in the past decade , since the time he famously predicted that they'd fall 30 % ...

... I wonder what his view on Bitcoin is , too .... nyuk nyuk .... haaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa !!!!

This is an interesting article for sure,but where is an ordinary joe bloggs supposed to invest their money.

I put some in forestry......sounds like its been a scam

I put some in a private super scheme..........shut down due to costs involved with complying with fma

I put some in the bank at a miserable 3.4%

I put some into the NZX.....not prepared to put any more(doing ok)

Housing seems my last option.

Saving/investing is too risky. Learn from the masses - Borrow and spend!

Sell your house and rent - in fact don't rent, live in a 5 star resort/cruise ship/hotel. Then spend every cent on having fun. In fact go into debt to do so - They can't repossess a holiday, meal out, concert...

Do not save for the future, someone else will cover that. After all it is unethical to let the elderly starve, freeze, etc... So society as a whole has a responsibility to provide.

If it all crashes before you retire, then don't worry - the debt is too big to call in. So there will be only two options

1. Write it all off

2. By virtue of the OBR effectively declare 99% of the population bankrupt.

My guess is the government will go for option 1. Anything else is political suicide. After all the entire tax voting public are the real "too big to fail"

*Note I am not a qualified financial adviser, any actions you take are your own, and I am not liable, responsible, or expected to care.

Seriously though, My actual advice is to do what all the rich are doing (only within your own budgetary constraints), they aim to be fully independent and self-sufficient.

- Buy some arable land with a permanent water source.

- Cultivate some vege gardens, orchards, and livestock.

- Look for an off the grid baseload power source, e.g. micro hydro with solar/wind backup.

- Build an above code house to protect and minimize damage from Earthquake, Storm, and intruders.

- Educate yourself on

- Basic first aid

- Horticulture/agriculture/farming

- Self defense

- basic mechanics, building, plumbing, and electrical work

or failing that, learn basic infiltration tactics, negotiation, and small weapons handling so that you can take over the "Rich"

Agree with you, up to "Seriously though..." then you got me lost

live off the grid living off the land ?

That’s a prison sentence not a solution

Unchanged since 2008 is the starring role of the rating agencies who seem to straining credibility in similar fashion to their AAA MBS ratings with that epic host of investment grade corporates. We need a competition to decide what the BBB now stands for.

Better Buy Bitcoin?

Beers a Better Buy?

bleeping bleepy bleep?

Beer will be at least worth something to trade unlike electronic currencies

Nobody will trust anything non tangible so Beer wins

Better Begin Bailing

... bought buggered bonds ...

Bull Bear Bust

Better Buy Bitcoin

I'm becoming more convinced that this picture explains a lot.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Population_growth#/media/File:World_popul…

Once all the new markets came on line through globalisation, we're now running out of anywhere new to sell stuff to. Solution, fill the void with more and more debt.

This may explain somewhat. Perhaps not as rosy as all get-out.

https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/27/chinese-bank-chief-found-dead-inside-hi…

The buildings don’t have opening windows so that was his best solution

Once the CCP find out why they would’ve shot him anyway

Mission Accomplished, QE I, II and III ?

Go get the book Sh-t Show the country’s collapsing and the ratings are great

By Charlie LeDuff

Out Now

Love Peggy Noonan, especially her article "There Is No Time, There Will Be Time" she wrote in the WSJ:

www.wsj.com/articles/SB122409083174236943

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.