By Rodney Dickens The arrival of the financial crisis introduced greater uncertainty on a number of fronts, making forecasting a nightmare. Comments by the RBNZ in the 10 December 2009 Monetary Policy Statement (MPS) reflect the greater uncertainty: "But perhaps even more uncertain than the outlook for the housing market is the extent to which its recent pickup is eventually reflected in increased consumer spending. There is a long-standing relationship between house price inflation and growth in consumer spending. We believe the household sector "“ which has faced the impacts of recession, falling house prices and rising unemployment over the past year "“ will be very cautious in its spending decisions over the coming year or so. In addition, banks are likely to be reluctant to allow households to leverage off recent house price gains, constraining the scope for debt-fuelled increases in consumer spending." On the same page of the MPS the RBNZ had the following to say: "However, the outlook for consumer spending has increased markedly. This is particularly so for spending on consumer imports, with the stronger New Zealand dollar acting to reduce the price of imported products." People would be forgiven for concluding that the RBNZ has contradicted itself (i.e. on the one hand, "we believe the household sector will be very cautious" and on the other hand, "the outlook for consumer spending has increased markedly").

By Rodney Dickens The arrival of the financial crisis introduced greater uncertainty on a number of fronts, making forecasting a nightmare. Comments by the RBNZ in the 10 December 2009 Monetary Policy Statement (MPS) reflect the greater uncertainty: "But perhaps even more uncertain than the outlook for the housing market is the extent to which its recent pickup is eventually reflected in increased consumer spending. There is a long-standing relationship between house price inflation and growth in consumer spending. We believe the household sector "“ which has faced the impacts of recession, falling house prices and rising unemployment over the past year "“ will be very cautious in its spending decisions over the coming year or so. In addition, banks are likely to be reluctant to allow households to leverage off recent house price gains, constraining the scope for debt-fuelled increases in consumer spending." On the same page of the MPS the RBNZ had the following to say: "However, the outlook for consumer spending has increased markedly. This is particularly so for spending on consumer imports, with the stronger New Zealand dollar acting to reduce the price of imported products." People would be forgiven for concluding that the RBNZ has contradicted itself (i.e. on the one hand, "we believe the household sector will be very cautious" and on the other hand, "the outlook for consumer spending has increased markedly").

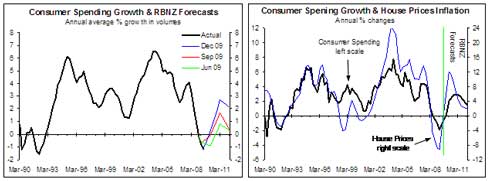

However, the left chart clarifies things. In the December MPS the RBNZ predicted a relatively weak recovery in annual average consumer spending growth relative to what has occurred during previous recoveries (blue line). However, the latest forecasts are less weak than the September predictions (red line) and much less weak than the June predictions (the green line). The RBNZ is now predicting a much stronger recovery in consumer spending than it was earlier in the year, but it is still predicting a relatively weak recovery by historical standards. In my view the outlook for consumer spending hasn't so much "increased markedly" as the RBNZ has belatedly realised what is happening. Back in June, when the RBNZ was predicting virtually no recovery in consumer spending growth for the subsequent two years (the green line in the left chart), I released a Raving that argued the recovery would come earlier than generally expected, justified by our leading indicator analysis. What is ironic is that early in the year, the RBNZ had no confidence in its own ability to underwrite an economic recovery. Despite cutting the OCR to the lowest level on record, the RBNZ was forecasting that the interest rate cuts wouldn't work. By comparison, while I have no faith in the RBNZ's ability to predict the future with any reasonable degree of accuracy, I do have faith in the central bank's ability to underwrite an economic recovery when it sets its mind to doing so. ( This is one of the reasons why clients of our monthly Interesting Times reports can expect much better insights into prospects for the likes of consumer spending growth than will be gleaned by reading the RBNZ's Monetary Policy Statements.)  The right chart above shows the "long-standing relationship between house price inflation and growth in consumer spending" the RBNZ mentioned, and the RBNZ's latest forecasts for both. The RBNZ has justified predicting a weak recovery in consumer spending growth in 2010 relative to what it is forecasting for house price inflation based on the view that "banks are likely to be reluctant to allow households to leverage off recent house price gains, constraining the scope for debt-fuelled increases in consumer spending." But I am suspicious this is another case of ill-founded or wishful thinking, for which there are plenty of precedents (e.g. the RBNZ assuming that low interest rates in 2003 wouldn't fuel a housing bubble and that the low unemployment rate that resulted from the experiment with low interest rates wouldn't fuel a labour cost inflation problem). I suspect that the RBNZ is overstating the importance of housing wealth in driving consumer spending. As the right chart above shows, house price inflation and consumer spending growth are highly correlated, but the best fit is coincidental (i.e. they go up and down together). This is not consistent with housing wealth being an important driver of consumer spending, but is better explained by consumer spending growth and house price inflation being largely driven by the same primary drivers (i.e. by interest rates and population growth/net migration). Analysis in our Interesting Times reports shows that interest rate changes take around nine months to filter through to consumer spending growth, while analysis in our Housing Prospects reports show that interest rate changes take around six months to filter through to the REINZ measure of house prices, which in turn tends to lead changes in the QV measure used in the chart above by one or two months. However, my biggest suspicion is that the RBNZ is indulging in wishful thinking. The RBNZ would love people to save more and spend less, which would help improve NZ's external deficit and make economic growth more sustainable. This is the desired "rebalancing" in the economy Governor Bollard has spoken about regularly this year. Seemingly driven by the desire that people spend a smaller proportion of their income and save a larger proportion, the RBNZ is predicting weak growth in consumer spending. Wishful thinking can become infectious amongst the economic forecasters. A case in point is the comments by the Westpac economists when they released the December quarter reading of the Westpac-McDermott Miller consumer confidence survey: "The current level of confidence is consistent with the RBNZ's 0.2% forecast for consumer spending growth in the year ended March 2010." The left chart below uses the Westpac-McDermott Miller survey as a leading indicator of annual average growth in consumer spending, with the best fit being with the survey advanced or leading by two quarters. This means the December reading of the survey gives insight into consumer spending growth in the year to June 2010 rather than March. The chart suggests that consumer spending growth could accelerate to around 4% in the year to June. The September quarter reading of the survey is most relevant to consumer spending growth for the year to March 2010, with it being consistent with growth accelerating to around 4% versus the RBNZ's conservative/miserly prediction of 0.2%.

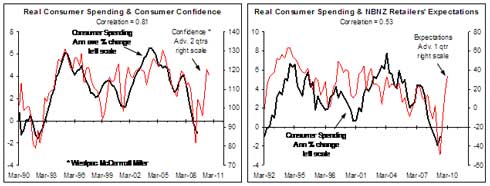

The right chart above shows the "long-standing relationship between house price inflation and growth in consumer spending" the RBNZ mentioned, and the RBNZ's latest forecasts for both. The RBNZ has justified predicting a weak recovery in consumer spending growth in 2010 relative to what it is forecasting for house price inflation based on the view that "banks are likely to be reluctant to allow households to leverage off recent house price gains, constraining the scope for debt-fuelled increases in consumer spending." But I am suspicious this is another case of ill-founded or wishful thinking, for which there are plenty of precedents (e.g. the RBNZ assuming that low interest rates in 2003 wouldn't fuel a housing bubble and that the low unemployment rate that resulted from the experiment with low interest rates wouldn't fuel a labour cost inflation problem). I suspect that the RBNZ is overstating the importance of housing wealth in driving consumer spending. As the right chart above shows, house price inflation and consumer spending growth are highly correlated, but the best fit is coincidental (i.e. they go up and down together). This is not consistent with housing wealth being an important driver of consumer spending, but is better explained by consumer spending growth and house price inflation being largely driven by the same primary drivers (i.e. by interest rates and population growth/net migration). Analysis in our Interesting Times reports shows that interest rate changes take around nine months to filter through to consumer spending growth, while analysis in our Housing Prospects reports show that interest rate changes take around six months to filter through to the REINZ measure of house prices, which in turn tends to lead changes in the QV measure used in the chart above by one or two months. However, my biggest suspicion is that the RBNZ is indulging in wishful thinking. The RBNZ would love people to save more and spend less, which would help improve NZ's external deficit and make economic growth more sustainable. This is the desired "rebalancing" in the economy Governor Bollard has spoken about regularly this year. Seemingly driven by the desire that people spend a smaller proportion of their income and save a larger proportion, the RBNZ is predicting weak growth in consumer spending. Wishful thinking can become infectious amongst the economic forecasters. A case in point is the comments by the Westpac economists when they released the December quarter reading of the Westpac-McDermott Miller consumer confidence survey: "The current level of confidence is consistent with the RBNZ's 0.2% forecast for consumer spending growth in the year ended March 2010." The left chart below uses the Westpac-McDermott Miller survey as a leading indicator of annual average growth in consumer spending, with the best fit being with the survey advanced or leading by two quarters. This means the December reading of the survey gives insight into consumer spending growth in the year to June 2010 rather than March. The chart suggests that consumer spending growth could accelerate to around 4% in the year to June. The September quarter reading of the survey is most relevant to consumer spending growth for the year to March 2010, with it being consistent with growth accelerating to around 4% versus the RBNZ's conservative/miserly prediction of 0.2%.  Having observed the phenomenon for over 20 years I can unfortunately report that it isn't uncommon for some bank economists to misrepresent what is implied by their own surveys, which doesn't help give economic forecasters a good name. The surveys aren't always accurate when used as leading indicators, but it is interesting to see that the NBNZ survey of retailers' activity expectations, like the Westpac-McDermott Miller survey, is pointing to a much stronger recovery in consumer spending growth than predicted by the RBNZ. The right chart above shows this survey pointing to consumer spending in the 2010 March quarter being up on the previous March quarter by much more than the RBNZ's prediction of 2.1%. This survey is less reliable than the Westpac-McDermott Miller survey, but together they make a strong case for expecting a stronger recovery in consumer spending growth than predicted by the RBNZ and by the economic forecasters on average. To clarify things, the RBNZ is predicting that consumer spending in the March quarter of 2010 will be 2.1% higher than in the previous March quarter, but for the year to March 2010 the RBNZ is predicting 0.2% growth over the previous March year. The impact of relative prices on consumer spending and housing demand Not only do I believe the RBNZ and most forecasters are being too pessimistic about near-term consumer spending growth prospects, but I also believe the RBNZ's view on the relative prospects for house price inflation and consumer spending growth is topsy-turvy. I believe the experience in the 1990s can be used as a benchmark for assessing the "normal" relationship between house price inflation and consumer spending growth (left chart below). During the recession in the early 1990s, house prices (right scale) fell around twice as much as the fall in the volume of consumer spending (left scale), while house prices increased around double the growth rate of consumer spending during the boom years of 1993-1996. Consumer spending growth also held up much better during the recession in 1998 because house prices had to pay pennants for having increased too much during the boom years. The most recent cycle was one during which the RBNZ's experiment with low interest rates contributed to an over-cooked boom in house prices, also known as a speculative bubble, with house price inflation running well above the two-for-one ratio relative to growth in consumer spending between 2003 and 2007. Reflecting the overdone house price boom between 2003 and 2007, house price inflation performed much worse than the two-for-one rule during the latest recession. Soft underbelly for house prices However, as covered in detail in our Housing Prospects reports, house prices haven't underperformed enough yet to restore normality. House prices are still too high relative to incomes and rents. Sub-6% mortgage interest rates are giving house and section prices a veil of affordability, but it won't take much of an increase in these sub-6% mortgage rates to expose the soft-underbelly of the housing and section markets.

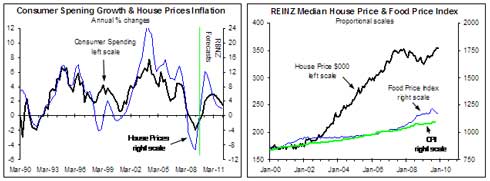

Having observed the phenomenon for over 20 years I can unfortunately report that it isn't uncommon for some bank economists to misrepresent what is implied by their own surveys, which doesn't help give economic forecasters a good name. The surveys aren't always accurate when used as leading indicators, but it is interesting to see that the NBNZ survey of retailers' activity expectations, like the Westpac-McDermott Miller survey, is pointing to a much stronger recovery in consumer spending growth than predicted by the RBNZ. The right chart above shows this survey pointing to consumer spending in the 2010 March quarter being up on the previous March quarter by much more than the RBNZ's prediction of 2.1%. This survey is less reliable than the Westpac-McDermott Miller survey, but together they make a strong case for expecting a stronger recovery in consumer spending growth than predicted by the RBNZ and by the economic forecasters on average. To clarify things, the RBNZ is predicting that consumer spending in the March quarter of 2010 will be 2.1% higher than in the previous March quarter, but for the year to March 2010 the RBNZ is predicting 0.2% growth over the previous March year. The impact of relative prices on consumer spending and housing demand Not only do I believe the RBNZ and most forecasters are being too pessimistic about near-term consumer spending growth prospects, but I also believe the RBNZ's view on the relative prospects for house price inflation and consumer spending growth is topsy-turvy. I believe the experience in the 1990s can be used as a benchmark for assessing the "normal" relationship between house price inflation and consumer spending growth (left chart below). During the recession in the early 1990s, house prices (right scale) fell around twice as much as the fall in the volume of consumer spending (left scale), while house prices increased around double the growth rate of consumer spending during the boom years of 1993-1996. Consumer spending growth also held up much better during the recession in 1998 because house prices had to pay pennants for having increased too much during the boom years. The most recent cycle was one during which the RBNZ's experiment with low interest rates contributed to an over-cooked boom in house prices, also known as a speculative bubble, with house price inflation running well above the two-for-one ratio relative to growth in consumer spending between 2003 and 2007. Reflecting the overdone house price boom between 2003 and 2007, house price inflation performed much worse than the two-for-one rule during the latest recession. Soft underbelly for house prices However, as covered in detail in our Housing Prospects reports, house prices haven't underperformed enough yet to restore normality. House prices are still too high relative to incomes and rents. Sub-6% mortgage interest rates are giving house and section prices a veil of affordability, but it won't take much of an increase in these sub-6% mortgage rates to expose the soft-underbelly of the housing and section markets.  This is partly why I believe the RBNZ is misplaced in predicting that house price inflation will significantly outperform the two-for-one rule next year (left chart above). I believe it is more a case of the RBNZ being too pessimistic about consumer spending growth prospects than being too optimistic about house price prospects, although it is likely to be a bit of both. This issue can be looked at from the perspective of relative prices, with the right chart above showing what has happened to the national median house price relative to the CPI, which measures prices of goods and services purchased by consumers, and the Food Price Index component of the CPI. The boom in house prices caused housing to become expensive relative to consumer goods and services in general, and relative to food prices. Faced with such a divergence in relative prices people will economise on housing in favour of the relatively cheaper consumer goods and services. This can be achieved by more people living in each house (e.g. younger people living at home for longer, more people squeezing into rental houses/flats, and by young couples and older people taking in boarders). By finding ways of economising on housing, people will be able to free up income to spend on the relatively cheaper consumer goods. The RBNZ even acknowledges this in the December MPS: "the outlook for consumer spending has increased markedly. This is particularly so for spending on consumer imports, with the stronger New Zealand dollar acting to reduce the price of imported products." The left chart below shows the impact of the exchange rate on import price inflation. If the NZD rises 20% on a trade-weighted basis against the currencies of our major trading partners, import prices generally fall around 10%, while if the NZD TWI falls around 20% then import prices rise around 20%. Major changes in the cost of imported oil can mean these rules of thumb aren't always so accurate, but things are working out normally at the moment. The rise in the NZD TWI this year is driving import prices down and this will be filtering through to lower prices for imported consumer goods. The right chart shows a useful case study of how major price changes can impact on consumer behaviour. It shows a somewhat haphazard inverse relationship between annual inflation in petrol prices and annual growth in the volume of spending on petrol, with the best fit being with petrol price inflation leading growth in petrol sales by one quarter. People do adjust their spending in response to the incentives provided by relative prices, like the relative cost of housing versus the cost of a plasma TV. It is a real world phenomenon rather than being just a curiosity of economics textbooks. All things considered, I can see more of a case for expecting consumer spending growth to outperform the two-for-one rule next year than I can see a case for housing price inflation outperforming. This is the opposite of what the RBNZ is predicting, which would make many forecasters nervous. However, having correctly predicted that the RBNZ's experiment with low interest rates earlier this decade would produce a housing bubble and a major labour cost inflation problem, and that the consequences would be a recession, I am happy to take a contrary view over prospects for consumer spending growth versus house price inflation next year.

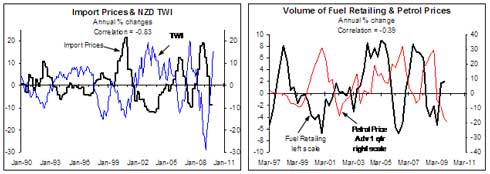

This is partly why I believe the RBNZ is misplaced in predicting that house price inflation will significantly outperform the two-for-one rule next year (left chart above). I believe it is more a case of the RBNZ being too pessimistic about consumer spending growth prospects than being too optimistic about house price prospects, although it is likely to be a bit of both. This issue can be looked at from the perspective of relative prices, with the right chart above showing what has happened to the national median house price relative to the CPI, which measures prices of goods and services purchased by consumers, and the Food Price Index component of the CPI. The boom in house prices caused housing to become expensive relative to consumer goods and services in general, and relative to food prices. Faced with such a divergence in relative prices people will economise on housing in favour of the relatively cheaper consumer goods and services. This can be achieved by more people living in each house (e.g. younger people living at home for longer, more people squeezing into rental houses/flats, and by young couples and older people taking in boarders). By finding ways of economising on housing, people will be able to free up income to spend on the relatively cheaper consumer goods. The RBNZ even acknowledges this in the December MPS: "the outlook for consumer spending has increased markedly. This is particularly so for spending on consumer imports, with the stronger New Zealand dollar acting to reduce the price of imported products." The left chart below shows the impact of the exchange rate on import price inflation. If the NZD rises 20% on a trade-weighted basis against the currencies of our major trading partners, import prices generally fall around 10%, while if the NZD TWI falls around 20% then import prices rise around 20%. Major changes in the cost of imported oil can mean these rules of thumb aren't always so accurate, but things are working out normally at the moment. The rise in the NZD TWI this year is driving import prices down and this will be filtering through to lower prices for imported consumer goods. The right chart shows a useful case study of how major price changes can impact on consumer behaviour. It shows a somewhat haphazard inverse relationship between annual inflation in petrol prices and annual growth in the volume of spending on petrol, with the best fit being with petrol price inflation leading growth in petrol sales by one quarter. People do adjust their spending in response to the incentives provided by relative prices, like the relative cost of housing versus the cost of a plasma TV. It is a real world phenomenon rather than being just a curiosity of economics textbooks. All things considered, I can see more of a case for expecting consumer spending growth to outperform the two-for-one rule next year than I can see a case for housing price inflation outperforming. This is the opposite of what the RBNZ is predicting, which would make many forecasters nervous. However, having correctly predicted that the RBNZ's experiment with low interest rates earlier this decade would produce a housing bubble and a major labour cost inflation problem, and that the consequences would be a recession, I am happy to take a contrary view over prospects for consumer spending growth versus house price inflation next year.  _________________ * Rodney Dickens is the Managing Director and Chief Research Officer for Strategic Risk Analysis (SRA), which is a boutique economic, industry and property research company. Rodney produces regular free reports on topical issues and on specific property markets. Find out more about SRA here and sign up to SRA's free reports here.

_________________ * Rodney Dickens is the Managing Director and Chief Research Officer for Strategic Risk Analysis (SRA), which is a boutique economic, industry and property research company. Rodney produces regular free reports on topical issues and on specific property markets. Find out more about SRA here and sign up to SRA's free reports here.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.