By David Skilling*

As is normal at this time of the year, I have been wading through a small mountain of 2025 outlook documents. As is also normal, there is a high degree of clustering – and path dependence – in these forecasts: common themes include ongoing US exceptionalism; a muted outlook for Europe/UK; and some caution on China.

Much of this consensus is sensible, but it discounts the potential for economic, political, and geopolitical dislocation: at-scale disruptions that affect economies and markets in material ways. My assessment is that there is a high likelihood of significant economic and geo/political turbulence in 2025, as global regime change strengthens – reinforced by a second Trump term, which I think will be more consequential than the first term.

Structural geopolitical pressures will continue to build, with important implications for the functioning of the global economy; and domestic politics across many countries will be turbulent – with material economic and commercial consequences. At the same time, there are powerful economic and technology dynamics that are positive for the economic outlook. Taken together, there is a very wide range of possible outcomes across economies and sectors over the next year and beyond

I am finalising preparations for client briefings on the 2025 outlook (get in touch if you would like to schedule a discussion). But to give an indicative sense of what we can expect in 2025, ten developments during December struck me as instructive (listed below in no particular order of importance).

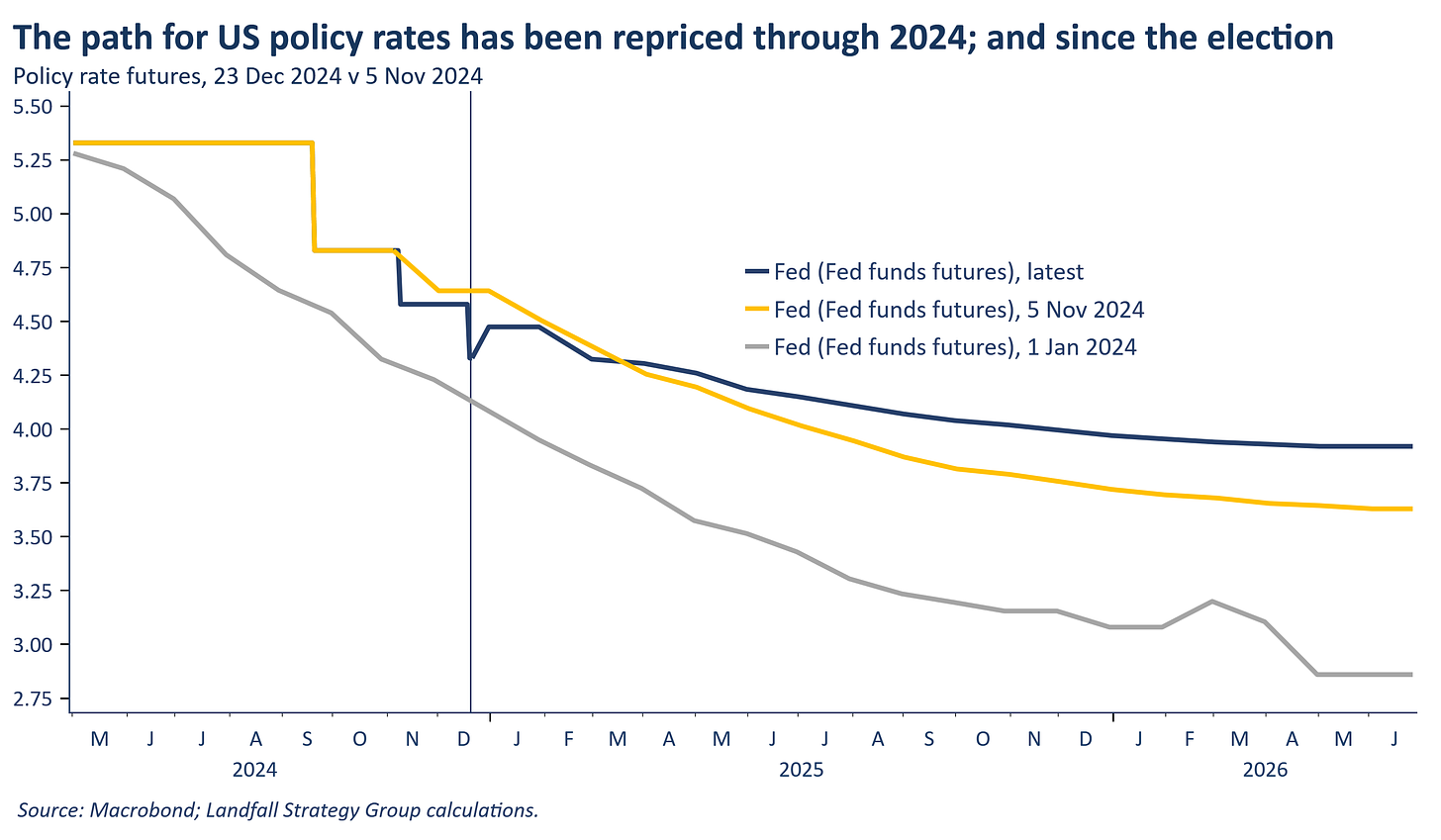

1. The return of inflation

The hawkish cut by the Fed in December – cutting by 25bps, but marking up its inflation and rates forecasts – caused a significant repricing in markets. The S&P500 was down by >3% on the day, and the forward rates path was marked up. This should not have been a surprise: inflation pressures remain persistent across many advanced economies; Trump Administration policies are likely to contribute to higher inflation readings in the US; and there are good reasons to think that we are moving into a structurally higher global inflation regime. Sustained inflation below 2% will be unlikely given the emerging global economic and geopolitical context.

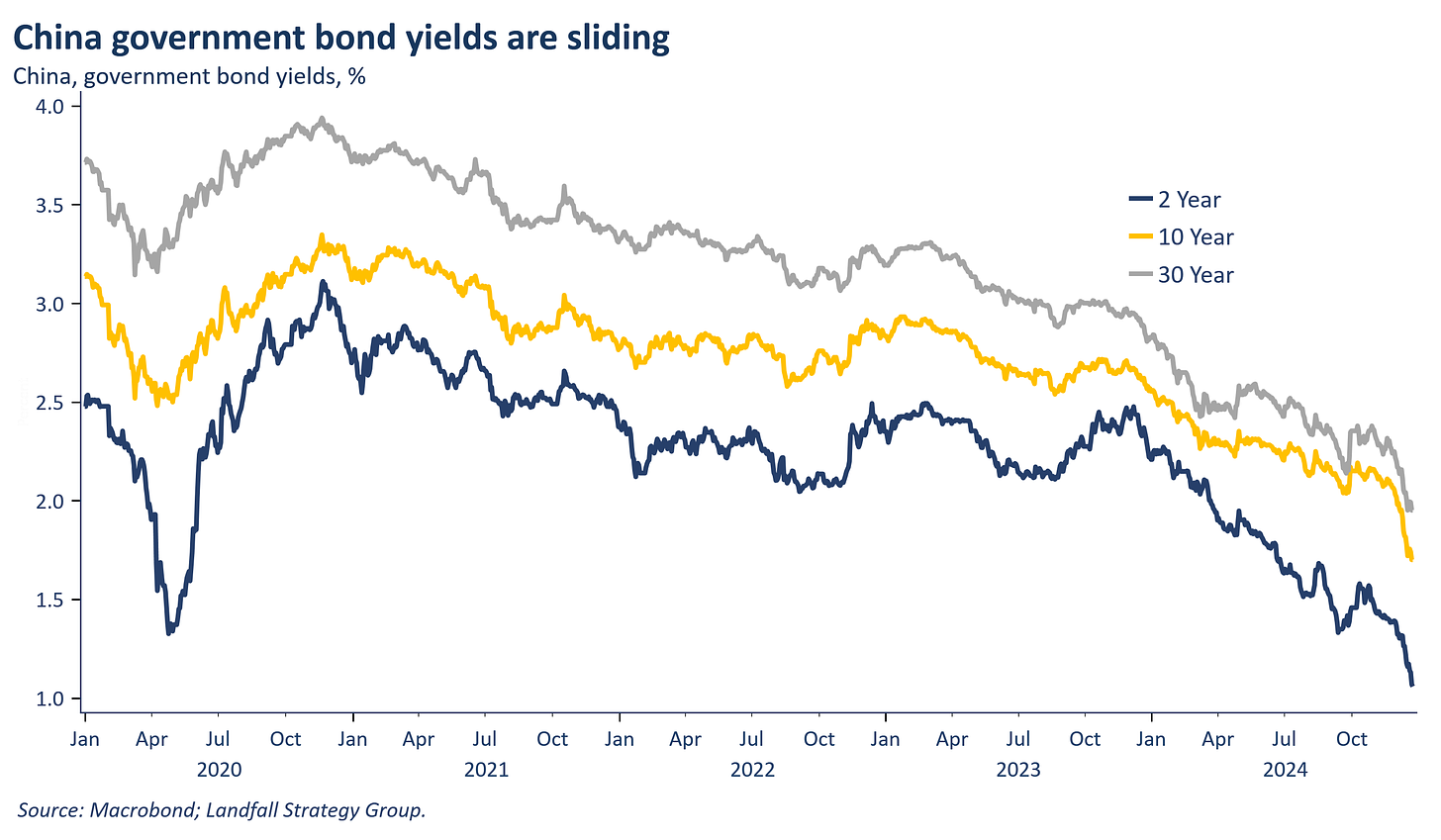

2. China’s Japanification

On the other side of the Pacific, Chinese bond yields continue to plumb new lows – the 2-year government bond yield is approaching 1%. This reflects Chinese monetary stimulus amid broad-based deflationary pressure, and a weak Chinese economy. Balance sheet recession dynamics are increasingly evident in China, even as China’s global competitive strength continues to manifest (discussed below). Economic and fiscal risks are building in China. Watch the CNY, which has continued to weaken in December and which may come under further pressure if meaningful US tariffs are imposed - with regional and global spillovers.

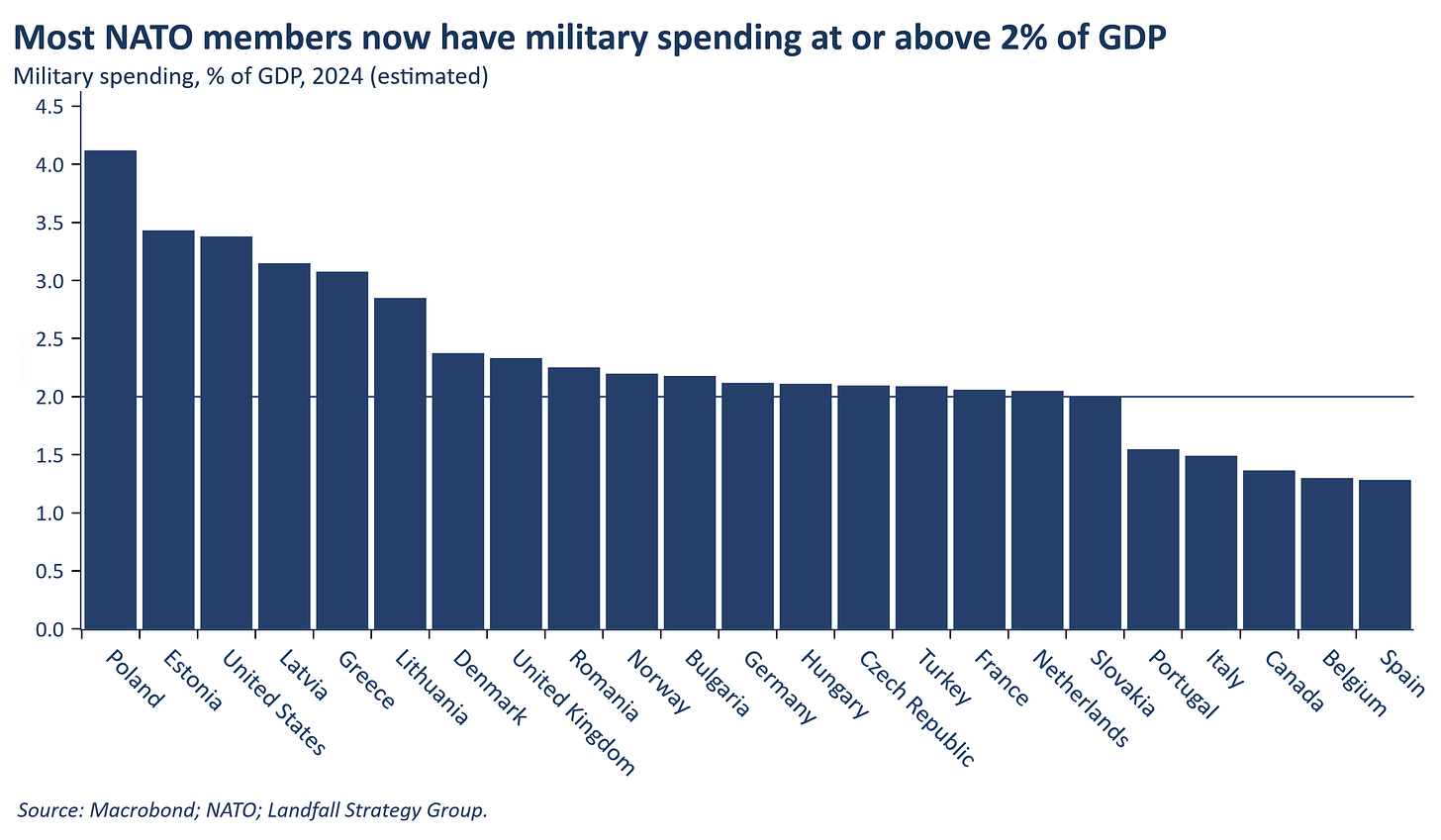

3. Wartime economy

Newly-appointed NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte delivered his first set-piece speech in mid-December, containing a series of blunt remarks. He said that ‘It’s time to shift to a wartime mindset’ in response to the growing threat from Russia as well as a more challenging security landscape more broadly. The direct implication is a need to ramp up defence spending and capability across Europe significantly, a process that has only just started and that will place significant pressure on already-strained government balance sheets. Firms and investors as well as governments need to position for elevate geopolitical risk in Europe and beyond.

4. Syria

In breathtakingly rapid developments in mid-December, HTS-led rebels overthrew the Assad regime and have begun to establish a new government. This is bad news for Iran and Russia; and offers a glimpse of a positively reordered Middle East – early signs are encouraging, although there is deep uncertainty and recent political history in the region counsels caution. This success was unexpected by most (except perhaps Turkey), and is a reminder of the elevated potential for fat-tail geopolitical shocks in 2025 as big and middle powers reprioritise. From Asia, to the Middle East and Europe, there is deep geopolitical fluidity.

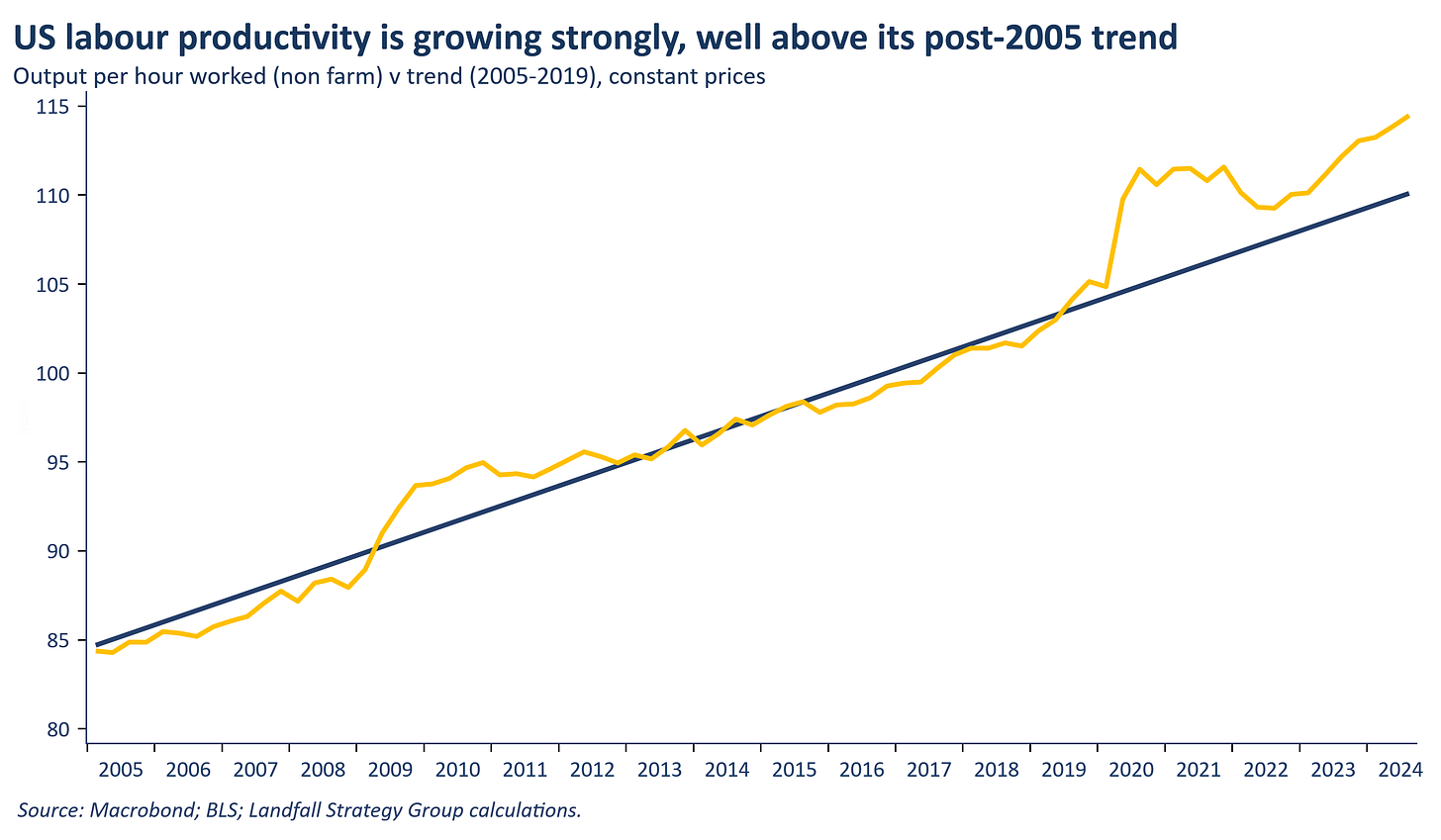

5. Technology goes exponential

For all of the talk about a plateau in AI models, impressive new releases in December from Google and OpenAI suggest no let-up in progress. And last week Google announced significant developments in quantum computing, with the technology coming closer to commercial use. In these technology domains, as elsewhere, exponential progress is being made. In not entirely unrelated news, the December release of US labour productivity data confirmed 2.0% growth in the year to Q3; the US, which leads in many of these technologies, has the stand-out labour productivity performance across advanced economies over the past few years. This provides some early, but encouraging, confirmation of my productivity renaissance thesis.

6. Populism

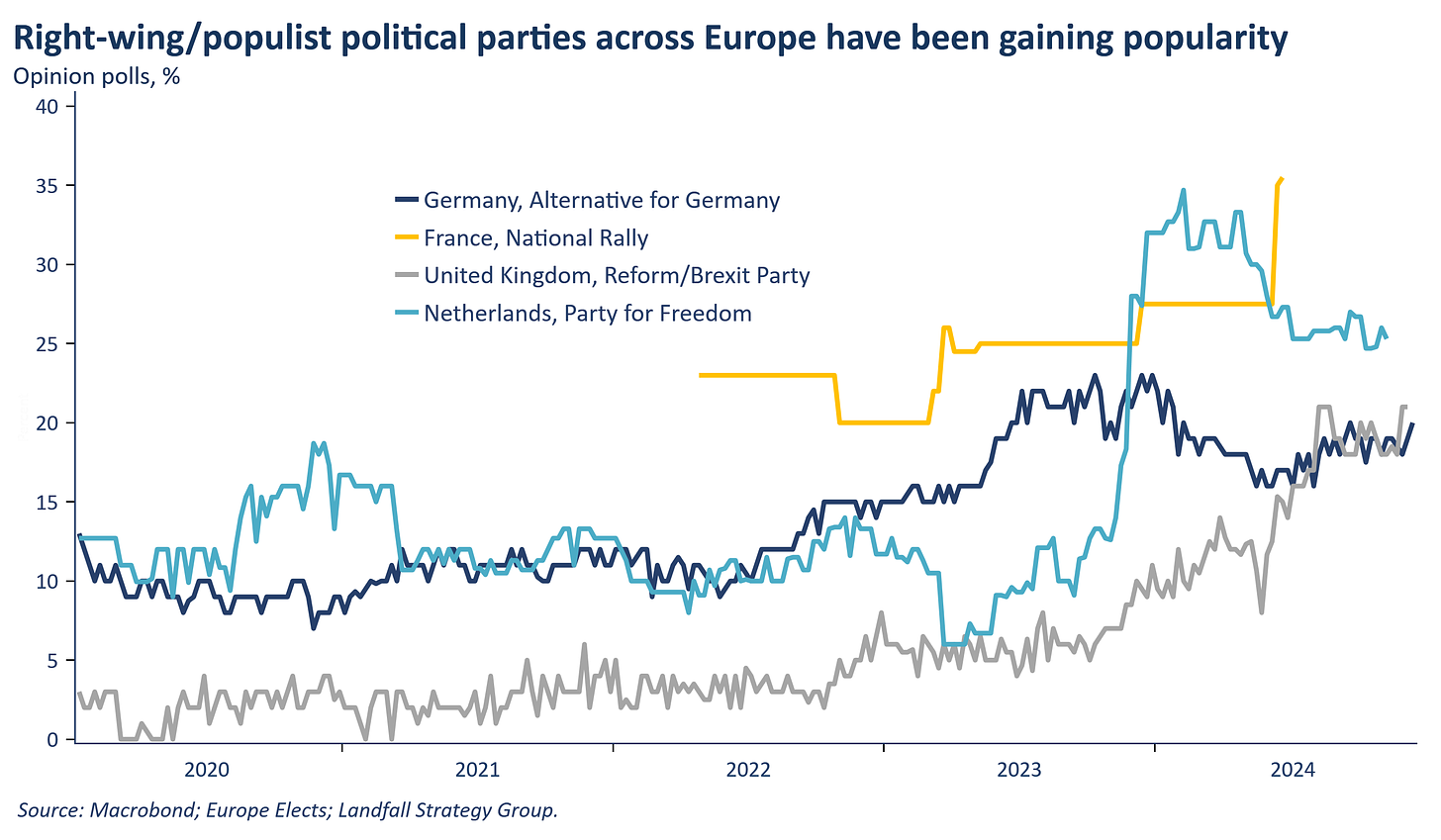

2024 was a year of elections. Although the centre broadly held (just), populist parties made meaningful advances (Germany, France, Netherlands, UK). Many incumbent parties are facing significant difficulties in governing effectively (note also South Korea). And expect more pressure. As one disruptive force, Elon Musk has recently encouraged support for the AfD to ‘save Germany’; and there are rumours of significant financing support from Mr Musk for the Reform Party in the UK. This type of support could have a major impact on the German and French elections in Q1 and Q2 2025, as well as on UK politics, with major implications for economic policy and outcomes. Significant domestic political disruption is also likely in the US, as Mr Trump begins his second term in January.

7. Tariffs & rumours of tariffs

President-elect Trump has threatened tariffs on a range of countries over the past month: 25% on Canada and Mexico (contributing to the imminent collapse of the Trudeau Government); and more recently suggesting tariffs on NATO members that don’t spend 5% of GDP on military spending (3.5% of GDP is apparently the real aim). And Panama is now in the firing line (and perhaps Denmark/Greenland). Tariff threats are partly about negotiating leverage to extract concessions, but I think it plausible/likely that we will see meaningful US tariffs imposed selectively through 2025. Equity markets are beginning to price for the possibility of actual tariffs.

8. Markets v politics

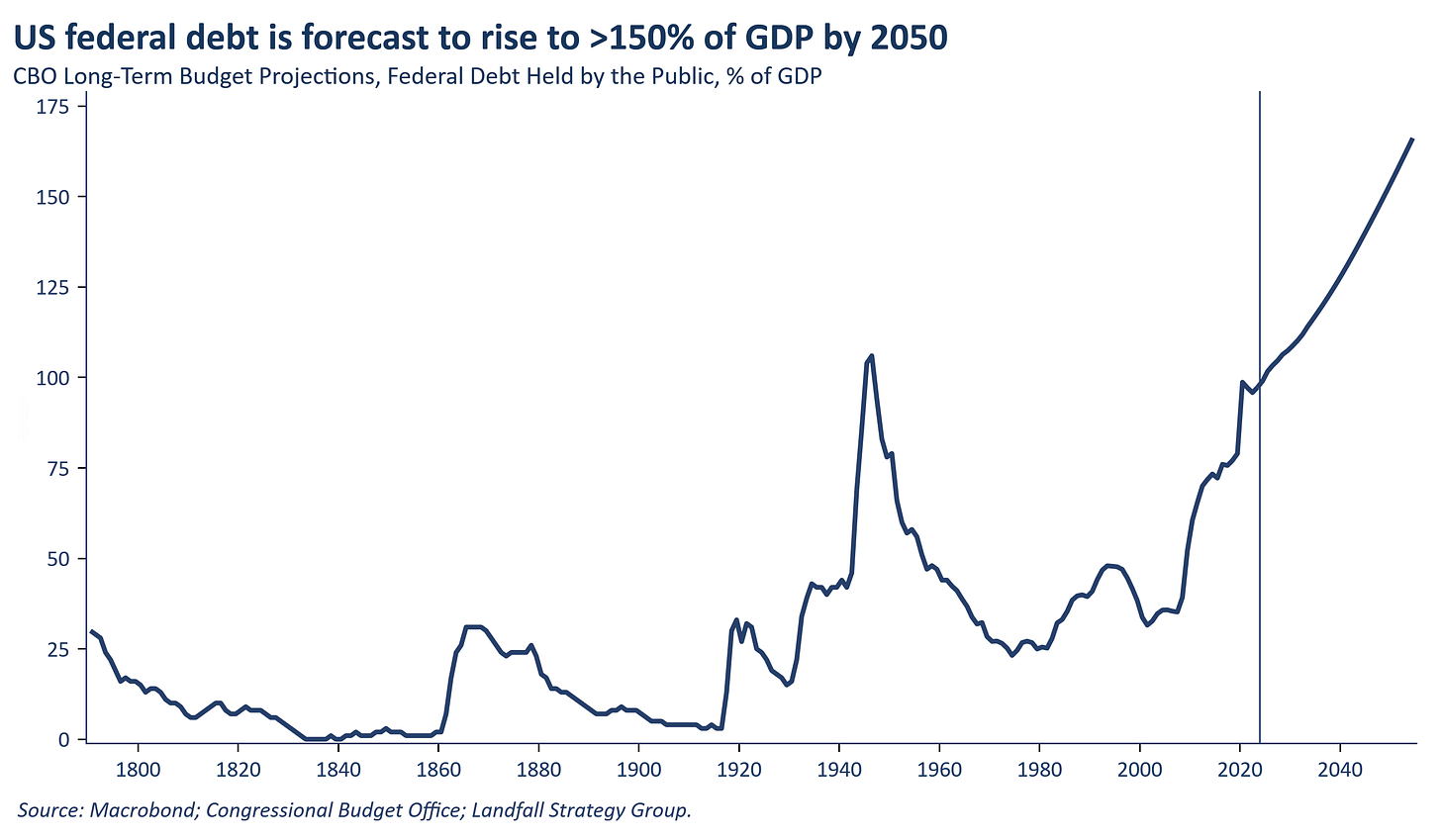

One of the themes in my notes has been the increasing tensions around fiscal policy, with public debt levels across many advanced economies and beyond moving sharply higher. This has not yet caused significant market ructions, aside from isolated examples (such as the Truss shock in 2022). But December saw investor noise in response to Brazil’s deteriorating fiscal situation as well as ongoing concern about the French fiscal outlook as a consequence of its political stasis. And bond investors look increasingly cautious about the US fiscal outlook. A clash is looming between markets and politics with respect to fiscal policy.

9. Supply chain weaponisation

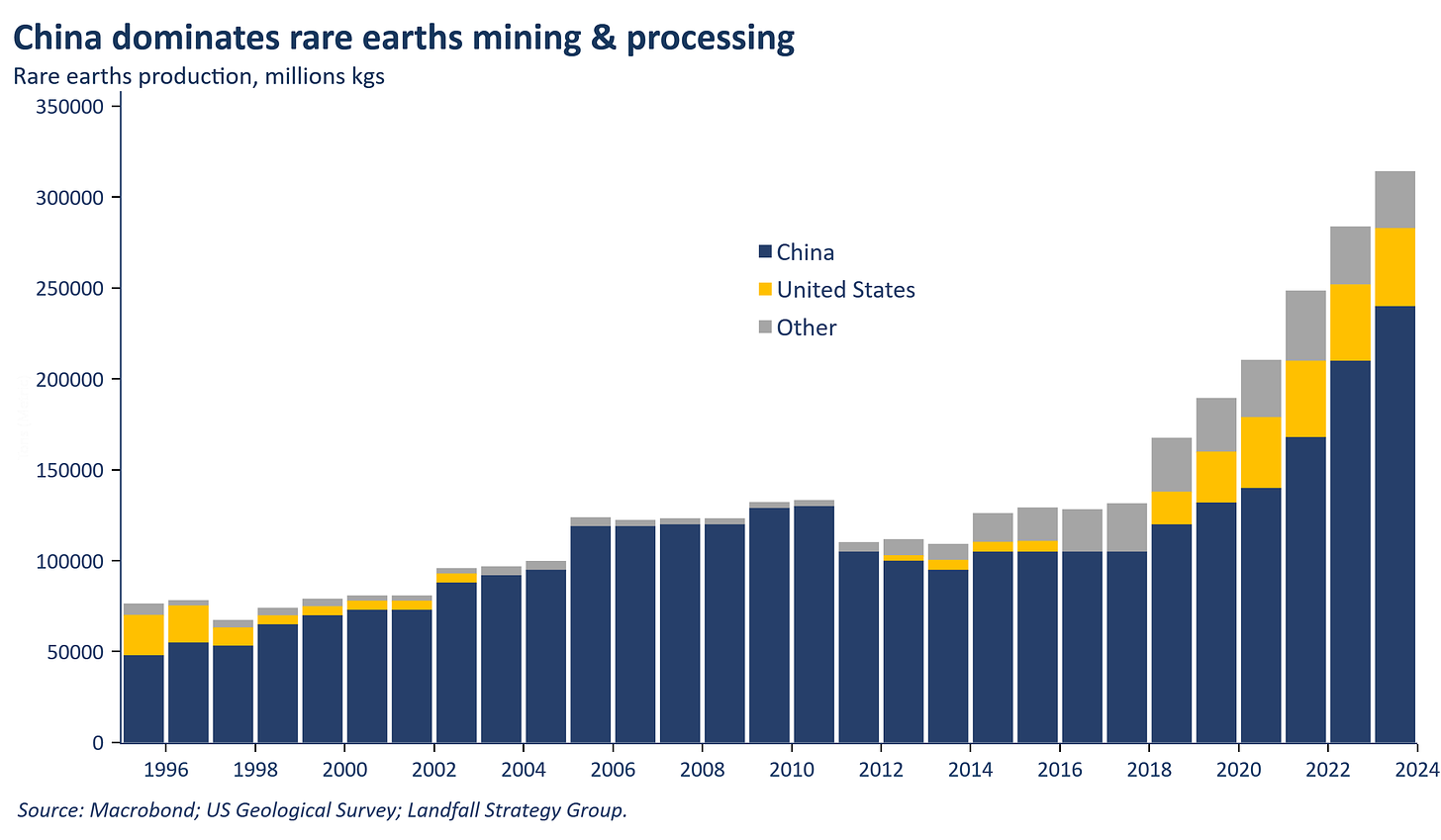

China has just imposed a ban on exports of gallium and germanium to the US after the latest round of US export restrictions on advanced technologies. China has developed dominant global supply chain positions across a range of critical raw materials, including rare earths. This gives it leverage in pushing back against tariffs and other restrictions by the US, the EU, and others – as well as the competitive advantage that arises from owning closed, vertically integrated supply chains. It will take time for the US and Europe to build out its own capacity; in the meantime, these supply chains will be increasingly weaponised.

10. Chinese mercantilism

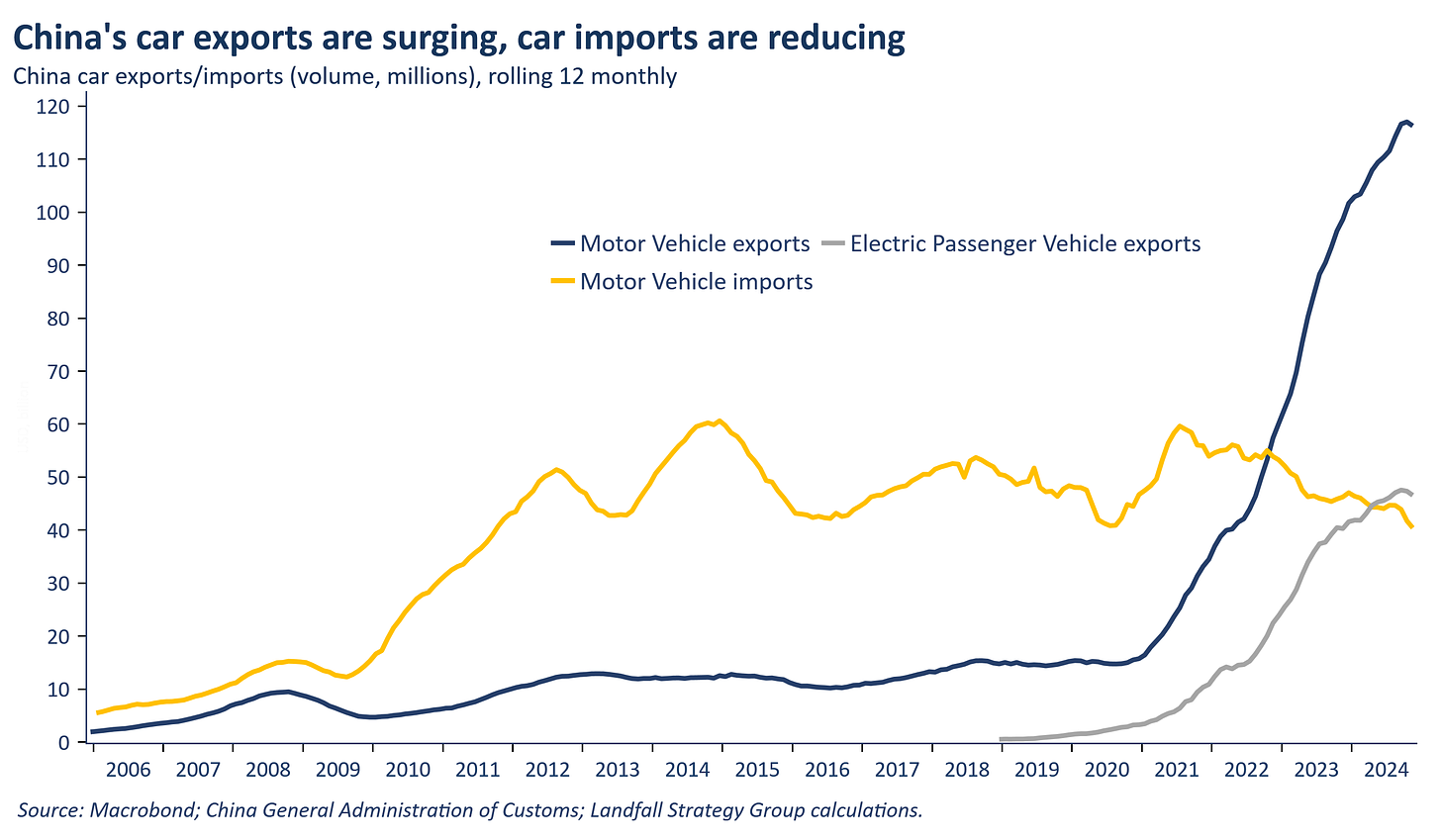

From ongoing industrial disputes at Volkswagen plants in Germany to this week’s proposed tie-up between Honda, Nissan, and Mitsubishi, the global spillovers from China’s aggressive mercantilism (notably in EVs, and associated supply chains) are becoming increasingly evident. China accounts for ~30% of global manufacturing value add, and continues to invest in ‘new quality productive forces’. This is not new, as regular readers of these notes will know, but these dynamics – and the reaction from other countries (including the US and EU) – are strengthening, and will shape globalisation through 2025.

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

26 Comments

NZ's 1 and 2 year mortgage rates have bounced up a touch from lows...

edit added below from US

Mortgage rates hit 7% on October 28, the highest level since the start of summer and up nearly one percentage point from the 18-month low they dropped to in mid-September.

A homebuyer on a $3,000 monthly budget can afford a $442,500 home with a 7% mortgage rate, the daily average 30-year fixed rate on October 28. That buyer has lost $33,250 in purchasing power over the last six weeks; they could have purchased a $475,750 home with the 6.11% average rate on September 17. That was the lowest level since February 2023.

for those who used to think that NZ rates where high compared to the ability to borrow in the USA for 30 years, might want to stop and consider what NZ rates might look like if US rates continue to rise.

https://www.bankrate.com/mortgages/30-year-mortgage-rates/

20-year & 15-year look better (at this time). I'd expect many many who started with 30-year mortgages, and have experienced inflation driven wage / salary increases, could refinance at these shorter terms.

inflation pressures remain persistent across many advanced economies

Campbell's tomato soup is the single best long run measure of food inflation. And the price has gone vertical. The can hasn’t changed. For more than 100 years, you get the same thing - ingredients, volume. And it reveals rapid inflation. Especially since 2020.

In 2023, the prevailing average sale was USD1.24 per can rising by 30% from the trailing 12 month average of USD0.95 per can in 2022.

Discounting on the soup is now rare. Before the Biden admin inflation got started, it was rare to see the regular sale price of a can of Campbell's Condensed Tomato Soup above USD1. In 2024, that's now the lowest prices at which American consumers can expect to pay for a can when they find it at a deeply discounted sale price.

We’re seeing a 1970 rerun: tariffs, deglobalisation, and a strong US dollar driving inflation and higher bond yields. Bonds are likely selling off not just from inflation but also rising US debt levels and a growing debt ceiling. Expect fixed mortgage rates to revisit 7.5% next year.

Faced with all this uncertainty ... There is a real possibility that central banks overcook things and/or consumer confidence fails, the rich stop spending, and we have a serious contraction, ala the last great one almost 100 years ago... and Independent_Observer will be correct. Old Chinese curse: May you live in interesting times.

Thanks for the call out although this isn’t a prediction but certainly a possibility.

Have a great Xmas everyone and enjoy your holidays with friends and family.

Tariffs on ally countries that don’t spend enough on military makes a lot of sense to me. Why should the US spend so much on military while the rest of us assume they will help us out.

If NZ has to spend 3.5% of GDP on military I assume that would be a significant increase?

Looks like we are less than 1/3 of that:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ms.mil.xpnd.gd.zs?most_recent_valu…

https://tradingeconomics.com/new-zealand/military-expenditure-percent-o…

Cough cough ..reserve currency advantage.

I once agreed with you, the Germans in particular have become very lax on defence since the 90s.

However, if you look at what the US actually gets for its trillions spent on the military, I would argue it’s *very* poor value. It’s become a syphon for tax dollars resulting in extreme waste, corruption and ineffective weapons systems produced by a cartel of manufacturers.

Check out “What’s going on with Shipping” on YT for an insightful look at how fragile the US Navy, merchant marine and shipbuilding has become. Hard to believe that more spending will magically fix this.

Sometimes continuity and predictably can be valuable in politics but often the most important and profound changes in society are triggered by outsiders. It's clear to me that the set policies that have been pursued by centrist political parties have now played out to the extent they've resulted in economic stagnation for much of society.

There was a very high risk that if things didn't change they'd stay the same.

Watch the CNY, which has continued to weaken in December and which may come under further pressure if meaningful US tariffs are imposed - with regional and global spillovers.

Good luck selling value-added ingredients and seeking premiums from the China market in 2025. You're going to need it and you'll have your work cut out for you.

Fully agree JC

Chasing the high value premiums are just a futile response to a low productivity high cost country called New Zealand

Not just Aotearoa businesses. Pretty much all nations have been targeting China as a value-add export market. Certain countries are still well primed to capitalize: Vietnam with high-value agriculture exports and Japan with similar high-value offerings in seafood, meat, traditional Chinese medicine made in Japan (kampo), etc.

Will be interesting to see how Fonterra goes with expansion into 2nd-tier urban markets. Also, Chinese still prepared to pay a premium for health-related products.

The similarities to the 1930s are disturbing...and with the added complication of being on the other side of the parabola.

This is mostly micro stuff, lost in the detail.

The major issues/events of 2025 are all political reactionary - Trump wanting Panama & Greenland (yes, let’s fight with our allies); German automotive & industrial collapse; desperation in Russia + Trump cutting off aid to Ukraine; Middle East power vacuums after Assad etc; more freak weather events; China not collapsing - sorry but they make *everything* and now have more engineering talent than everyone else combined; US isolation and general descent into a superstitious medieval culture under the GOP.

Very hard to descend into GOP darkness due to a single term... after so long in dem control?

Engineering normally trumps wokeness.

Can you imagine how powerful China would be if it switched to democracy?

A healthy democracy would benefit China - both its long term economy and the wellbeing of its citizens. But democracy is a fragile creature. The USA with massive cash and large dominant military were unable to grow democracy in the countries it invaded and ruled; barely a flicker in Iraq, Libya & Afghanistan. More likely to result in Chinese anarchy and they have a history of anarchy with warlords.

Since when has a democracy been that great. China is doing just fine it's about the right person leading the country end of story. If the choice was just Trump or Kamala how was that so much better ? We have a choice between idiots.

I am very worried about AI

models just know how to scheme and act dumb...

2025...can't help wonder how many of the leveraged specubestors on here will actually refuse to pay 27.4c per day to allow them to continue to push their narrative. For supposedly wealth property owners, that would be really funny.

Maybe it's just choosing what money is spent on wisely. To get somewhere, it's better to determine needs, not wants. It's to easy to subscribe to everything under the sun on the internet and suddenly realize how much money is going on subscriptions per month (on things often hardly used)

Nobody talking about the value of the NZD? ... At current levels - or below - it could end up being a major story line for 2025. (And not in a good way.)

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.