This is a re-post of a February 21, 2017 article first posted here.

By Keith Woodford*

I live at Kennedy’s Bush, one of the focal points of the fire. We watched as the fire went past us on 13 February, only to be threatened again on 15 February. We were evacuated for 72 hours, but were then able to return to our home with our property totally unscathed. As I write this, I can hear the helicopters hard at work again passing overhead with their monsoon buckets, and planes dropping fire-retardant materials.

In this post, I share the chronology of the fire as my wife Annette and I saw it from Kennedy’s Bush. It is largely a pictorial story from the photos we took (click once on each photo to enlarge and show the detail, then use the back button to return to the story), but with a specific focus on the chronology and the contextual background.

First, I want to provide some background for those who do not know much about Christchurch and its Port Hills.

The Port Hills lie in an arc on the edge of Banks Peninsula to the east of Christchurch. They separate the city from Lyttelton Harbour, rising to a little over 500 metres. They formed some millions of years ago when Banks Peninsula was a volcano with multiple eruption points.

In the past, Banks Peninsula was heavily forested. But that was more than 100 years go. Now it is predominantly grassland and exotic pine plantations, but with some nature reserves and some man-assisted regeneration of native trees. The Port Hills are also an important playground for the people of Christchurch, with many walking and mountain-bike trails.

The climate of Banks Peninsula is complex. In summer time, hot norwesters (which weather people call ‘adiabatic’ or ‘fohn winds’ ) flow across the plains from the Southern Alps. In spring and summer, strong but cool north-east winds often build up in late morning, coming in from the ocean. Then at night, typically some time between 8pm and midnight, they die away again. At times, southerly storms flow in from the ocean, and the shape of the trees high on Banks Peninsula tells us that these southerlies are dominant vegetation-shaping forces.

February is typically the month when Christchurch experiences its biggest dry periods, with summer rainfall less than half of evapo-transpiration. At this time, the hills take on a tawny hue, with dry grass-seed heads waving in the wind.

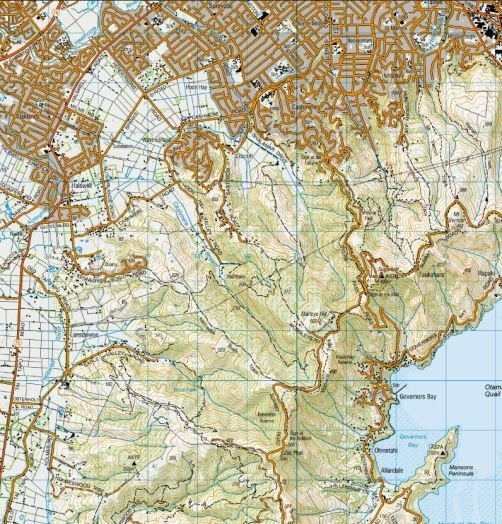

And now to the fire itself. In telling that story there are several place names that recur. These are Lansdowne Valley, Kennedy’s Bush, Hoon Hay Valley, Westmorland, Worsley Spur, Marleys Hill, and the Sugarloaf TV and radio transmitters. These are shown below on a topographical map of the area.

Christchurch topo map (Click to enlarge)

Of course there are many stories of the Port Hills fire, and most of those will remain untold. The people who worked so hard and in many cases heroically in the air and on the ground, are typically not the type of people who then write their stories. I have myself worked in search, rescue and recovery (when I was a much younger man) and despite use of pen and computer as my lifelong tools of trade, I have not written of those events. ( I possibly will do some day.) With this story, I write it from the outside as an on-site observer, with some understanding of the complexities when men and nature interact, rather than in any way as a participant.

The fire began about 5.30 pm on Monday 13 February. The initial unconfirmed evidence is that it was caused by part of a transformer falling from a power pole. What is known is that it started on the lower slopes just above Early Valley Road in the Lansdowne Valley, and was preceded by a loud bang. The fire was seen almost immediately by local residents who called the emergency services, and then got to work, with garden hoses and wet sacks, protecting their own properties from the rapidly growing flames crossing the grassland slopes. Remarkably, most were successful, with nearly all houses being saved on the upper side of Early Valley Road where the flames were raging.

I first became aware of the fire soon after 6pm as I was driving home. I could see huge plumes of smoke billowing up from the Halswell area. John Campbell was already reporting the fire on his National Radio Program.

My own home is less than 2km from the starting point of the fire, but the westerly wind was blowing away from where we live and we were protected by the lee of a small hill. It was only by heading up Kennedys Bush Road that we could see what was happening.

Looking across to the Lansdowne Valley from Kennedy’s Bush Spur on 13 February 7.59 pm

Above the Lansdowne Valley 13 February 8.05 pm

It seems that the first three or so helicopters to be mobilised with monsoon buckets played a key role in saving these houses (above). Within two hours, the fire had essentially passed on through these grasslands, although the shelter belts were still providing a challenge.

From Kennedy’s Bush Road, looking south towards the Rim of the Port Hills, 13th February 8.06 pm

Looking up the Lansdowne Valley, from the plains, 13th February, 8.22 pm

Kennedy’s Bush Spur, smoke from Lansdowne Valley (out of sight), 13 Feb 8.29 pm

Hoon Hay Valley 14th February 7.06 am

By Tuesday morning, 14 February, it seemed that the fire was contained, at least on the Christchurch side of the hills, and that was the essence of the message from authorities to the public. The photo above shows the wind still blowing the smoke from the west, across the photo from right to left. However, high on the Port Hills the fire was still raging. Indeed there were two fires, with a second one having started at the Marley’s Hill carpark off the Summit Road about 7 pm on the Monday night. The two fires can be seen here, apparently still separate, although later to join. The cause of the second fire remains unclear, but almost certainly was caused by people, either by accident or an act of arson.

I spent that Tuesday out at Lincoln University, assuming as most people would have done that the 14 helicopters with their monsoon buckets had matters under control. It was only when I returned home that evening I was shocked and devastated to hear that helicopter pilot Steve Askin, a relative and friend of some of my colleagues, had been killed, possibly caused by a snagged monsoon bucket.

With hindsight, it seems that Tuesday was a lost opportunity. No civil defence emergency had been called, and far too much reliance had been placed on the helicopters which returned at dusk to their operational base near Tai Tapu, adjacent to the Lansdowne Valley, or headed back to the main airport. Also, only very limited quantities of fire retardant had been flown, apparently due to a lack of supply.

Hoon Hay Valley, 15th February, 7.17 am

By Wednesday morning 15th February, the wind had changed from west to a gentle southerly. This was enough to drive the fire down the Hoon Hay Valley. Despite the cool night, with temperatures dropping to 2 degrees C, all of a sudden things were looking more serious on our side of the Port Hills.

Halswell Quarry, 15th February 10.23am

The helicopters were now using the ‘duck pond’ in the Halswell Quarry off Kennedy’s Bush Road as a source of water. The smoke in the above photo is coming from the Hoon Hay Valley.

Looking towards the back of the Halswell Quarry Park on 15th February at 1.01 pm

By 1 pm, I was becoming concerned, with the rising easterly wind. I knew that Hoon Hay Valley with its pine plantations was burning, and I could see potential for the fire to travel back over the ridge to Kennedy’s Bush Spur with its 200 houses.

Above the Halswell Quarry, 15th February, 1.03 pm

Halswell Quarry, 15th Februry at 1.21 pm

However, the general atmosphere down at the Halswell Quarry was somewhat relaxed. The school children had been brought along in their class groups to watch an inspiring educational event, with helicopters lining up to fill their monsoon buckets. I recall no presence of any authorities apart from the helicopter pilots, but there may have been one person there in a high viz vest.

At the top of Kennedy’s Bush Road, 15th February, 2.17 pm

By 2 pm I was becoming increasingly concerned, so I headed to the top of the road on Kennedy’s Bush Spur. Remarkably, there were no authorities there. I realised that once it dawned on the authorities as to what was happening, we would all be evacuated, so I called my wife to say it was time to start thinking about getting home and collecting up key possessions.

From high on Kennedy’s Bush Road, looking towards the south east, 15th February, 2.27 pm

The winds up here were now easterly, posing a bigger threat than if they had been north-east. Clearly, we were in the line of fire. As I returned down the road I saw one policeman, stopped in his car, talking to a local, but no sign of fire crew or civil defence.

Above Halswell Quarry, 15th February, 3.04 pm (There are six helicopters to be seen in this photo)

Helicopters coming and going from the Halswell Quarry ‘duck pond’, 15th February, 3.05pm

By now, it was obvious that the helicopters were unable to control the developing firestorm. There were six of them heroically working the pond, working with apparently minimal separation, dumping their loads on the ridge separating Kennedy’s Bush from the Hoon Hay Valley. Elsewhere there would have been another (approximately) 8 helicopters fighting the battle on other parts of the Port Hills.

Halswell Quarry 15th February, 3.19pm

Above the Halswell Quarry, 15th February, 3.25 pm

The evacuation started about 4.30 pm, with people up the top of the road given no time to collect anything. By Wednesday 6 pm, the police had reached the bottom of the road, going from house to house, and we had all departed in our cars, some more prepared than others. By now a Civil Defence Emergency had been declared, and this was allowing much greater resources to be brought to bear. But it was now getting late in the day.

Hoon Hay Valley from Sparks Road, 15th February at 7.23 pm

Worsley Spur, 15th February, 7.43pm

Further around the hills to the north-east, and beyond Westmorland, the fire was attacking Worsley Spur. Several houses were lost on the Worsley Spur.

Between Westmorland and Cashmere, February 15th at 7.44 pm

Slopes on the north-east side of Worsley Spur, 15th February at 7.45 pm

Worsley Spur, with Westmorland on the left, on 15th February at 10.11 pm

Between Westmorland and Worsley Spur on the right, and Cashmere on the left, 15th February, 10.45 pm

Fire across Dyers Pass Road with the lights of the Sugarloaf transmitters above and left of centre. 15th February 10.48 pm

Once the helicopters withdrew at dusk, all hell broke loose.

The fire did come over the ridge between Hoon Hay Valley and the Kennedys Bush Spur, with 200 houses at risk. It was very fortunate that the wind then died away about 11pm, sufficiently for the fire to lose much of its energy.

At the top of Kennedys Bush Road and beyond (Source unknown) Thursday 16 February

Details of how and why it stopped where it did stop are unclear (to me). Certainly, the wind died down about 11 pm. I am told there were no fire crews up there, but maybe there were. Maybe fire retardant played a role, but I am doubtful. It is only today (21 February) that fixed wing planes have been applying retardant up there, brought in from Australia. All I know is that if the fire had got into what is known as the ‘Crocodile Gully’ (in the left of the photo above) then the whole spur and much of the pine forests above the Quarry and below the houses were at huge risk. It was only 30 metres from happening.

The upper zone of Kennedys Bush Spur six days after the burn, with the Quarry Park below (21 February)

The top of Kennedys Bush Road after the fire had gone through. (This photo was taken 6 days later, 21 February, when the cordon was relaxed.)

On Thursday 16 February, civil defence systems finally came into place which should have occurred earlier. Suddenly there were lots of fire tankers, civil defence and police, albeit struggling to get co-ordination. Heavy machinery came in to construct firebreaks, and people could be seen checking for hot spots.

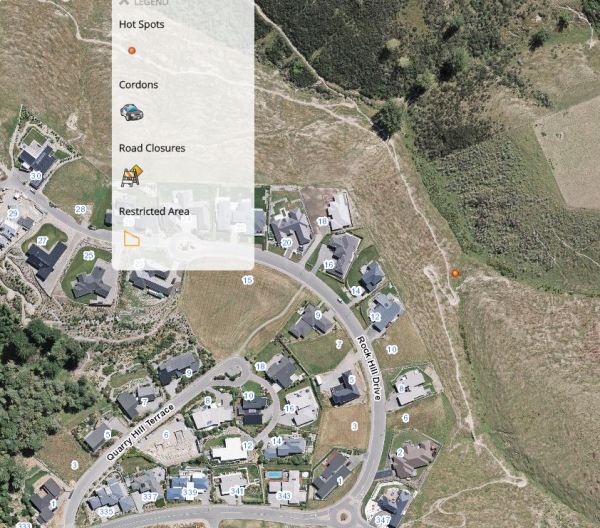

By Saturday 18th February, the 200 Kennedys Spur families were getting very keen to get back to their houses, to address the needs of pets, and to get back to their normal lives. Although 11 houses were lost in the fire, none of those were at Kennedy’s Bush. However, the authorities who had been slow to react as the fire developed, were also slow to let residents return. They were concerned that if they let us return, then they might have to evacuate us again in one or two days. They were also concerned about supposed hot spots, although when eventually the ‘hot spot’ map was produced (see below) there was only one nearby and this was probably a ‘falsy’ as the fire had not reached that point, and there were also no tree roots there to create an underground hot spot.

Supposed ‘hotspot’ at the top of Kennedy’s Bush Road, accessed from Christchurch City Council website 18th February at 8.34 pm

Some families did manage to get back to their homes on Saturday 18 February and the remainder on 21 February. Tuesday February 21 also saw major applications from the air of retardant (imported from Australia) across Hoon Hay Valley and Kennedy’s Bush Spur.

Now, some 8 days after the fires began, we can start to reflect. We can wonder in awe at all of those Port Hills houses that are completely surrounded by burned-out land but which are still standing – albeit no doubt with smoke damage in many cases. There must be many untold stories about people on the ground and in the air who went well beyond the call of duty to save those houses.

Houses on Worsley Spur, surrounded by burnt-out land (21 February)

The Christchurch Adventure Park (with chairlift left of centre), 21 February

Hoon Hay Valley, 21 February

As a community, we will now need to reflect on the type of vegetation we wish to have on the Port Hills in future. And our officials will need to reflect as to why the response mechanisms were so delayed and so shambolic. It is not as if this is the first disaster New Zealand has had to face. Why do we not have major supplies of fire retardant in the country ready and waiting? And why do we have to rely on individuals rather than proper systems that kick into gear immediately? But they are all questions for the future.

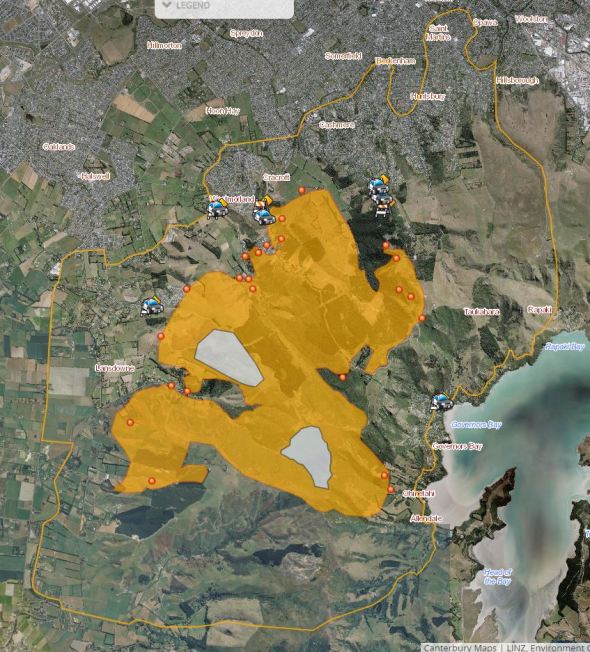

Finally, below is a map showing the boundaries of the fire on both sides of the Port Hills.

Accessed from the Christchurch City Council website on 18th February at 8.20pm (https://www.ccc.govt/services/civil-defence)

*Keith Woodford is an independent consultant who holds honorary positions as Professor of Agri-Food Systems at Lincoln University and Senior Research Fellow at the Contemporary China Research Centre at Victoria University. His articles are archived at http://keithwoodford.wordpress.com

4 Comments

I have a vague recollection of a dangerous fire on Clifton hill in the 1960's but cannot recall anything of this catastrophic nature on the Port Hills ever before? Obviously the risk has always been there but now the question is in this day, given the technological fire fighting and communication advances, how could it have got so out of control? Explanation must be partly the vegetation, areas of too long grass etc and surely the actual management of the crisis. If those concerns are not sorted out it will surely happen again, say Evans Pass, Godley Head for example, and it might be soon. Unfortunately Christchurch has an over supply of hoons and goons in cars who just love destruction and being a copy cat is a base element of their mentality.

Thanks Keith, it's good to hear from a local. California have strict bans on vegetation.

http://calfire.ca.gov/resource_mgt/resource_mgt_EPRP_FuelsTreatment

I was concerned this year, so I got topping around the house. I am amazed that we have no fire breaks in NZ i suspect because it's not a yearly event. I had the thrill of seeing a lightning strike start a fire in California while I watched it consumed 600 acres in 30 minutes, within 20 minutes an Iroquois was in the air and climbed to probably 7,00 feet and acted as air control, then about 20 planes started dropping retardant, then lots of specialised bulldozers adapted to fire control turned up, the fire was under control in 4 hours, they have the option of big jets but the biggest with us is a 4 engine jet BAE regional jet.

There is a lot of debate around the effectiveness of aerial fire control, with some saying it looks good but largely ineffective.

http://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-wildfires29-2008jul29-story.html

When I was young I worked on a station with a large two story dwelling, under all the trees was growing periwinkle, ivy and another ground vines, grown to stop fire spreading.

Mostly fire control needs to fall on the house holder, when it's a lifestyle block, control grass, have no burn zones, plant sensible trees etc.

If you want to live in a real fire zone, go to the parts of the States where the pine beetle has destroyed forests.

http://www.hcn.org/issues/44.8/bark-beetle-kill-leads-to-bigger-fires-r…

I was surprised at the lack of heavy machinery in the CHCH fire. The problem with fires is they are all unique, but if you live in Ca you grow antenna when lightning comes. My daughter got caught up in a large thunder storm while rafting the Kalamath river, she said that over a hundred fires started and almost all controlled by ground forces. She was in wonder as bear, deer and other animals of the forest crossed the river in front of them, while they sheltered under a bluff.

No Firebreaks

We are in Coastal Otago now

Lot of plantation forests around us. No Firebreaks. As I watched the Port Hills fire unfold on TV it was most notable the absence of firebreaks. Lot of forestry established in the subject areas over the past 10+ years. The steep hill terrain was said to be impossible for heavy equipment. So firebreaks have to be mandated and established at the outset

But no established or natural firebreaks. What about back-burning in winter and spring?

Grass fires can travel horizontally at 45+ kph in a reasonable wind

Indeed, the lack of firebreaks and heavy machinery early on was a puzzle. The notion that such gear (I used to run mid-size Cats in my Tonka Toy days - one tale here http://waymad.blogspot.co.nz/search?q=scraper ) cannot operate on Port Hills slopes is questionable - how else do the loggers get the trees out? Answer - dozers, skidders, feller-bunchers.

From my perch way out of the way, north-east near the beach, using some dozer clout to make firebreaks well ahead of the fire, may have made a critical difference. But the real question in all of this was - why wait so long to call a state of emergency, or at the very least, to call NZDF and say - have them Herc's on standby.

And why were there not firebreaks, open, cleared of slash and trash, and accessible to ground vehicles, to begin with, through those plantations?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.