This article is a re-post from the MFAT Briefing, here.

Summary

- China’s property market accounts for around a third of China’s GDP. In 2024, the sector entered its third consecutive year of decline.

- Property investment fell 10.2% in the first seven months of 2024. Some private developers’ earnings are not high enough to cover maturing debts. Amid financial difficulties, developers are retreating from third- and fourth-tier cities and focusing their shrinking on more affluent and less first- and second-tier city markets.

- The weak property market dampens consumer confidence and by extension domestic consumption because Chinese households typically store much of their wealth in property. Significant debt held by private property developers represents systemic risk in China’s financial system.

- In May 2024, Beijing announced policy focused on reducing unsold housing inventory, stimulating demand, and ensuring sufficient access to finance for property developers. This was built upon in September 2024, with a CNY 1 trillion (~NZ$ 235 million) package of monetary stimulus. Taken together, the support has been calibrated to stabilise property prices and ease the financial stress faced by developers – not to return the market back to its previous heights.

- October data showed an improvement in housing sentiment. In October, home sales by value only fell 0.2 percent yoy, compared to a 16.5 percent drop the month before. However, the overall picture remains challenging with both investment in real estate and number of new builds dropping by their fastest rate in October year-on-year.

- While forecasting the highs and lows of markets is a fraught business, the current consensus among commentators appears to be that 2026 may be the year of house price stabilisation.

- China’s property downturn has had direct impacts on New Zealand exporters:

- 1) Non sector-specific: lower consumption trends in China’s economy, influenced by low consumer confidence in the property downturn, has been a headwind downgrading consumption of some New Zealand exports. As Chinese consumers seek greater value, to remain competitive some New Zealand firms have lowered prices.

- 2) Sector-specific: structural change in the property sector has weakened economic activity in related sectors of construction and furniture-making, both of which import New Zealand logs and wood products. This impacts demand and global prices for New Zealand logs. The impact on sector-related services exports (e.g. architectural design) remains to be seen.

The depressed property market is China’s most significant challenge to its COVID 19 recovery and to achieving sustained economic growth. The property sector's significance stems from its integration with other major industries (particularly construction), the estimated 2.5 million jobs it creates, and its role as the most important asset class for Chinese households (in 2019 it made up 70 percent of urban households’ assets – the rest being low-interest bank deposits, cash, or volatile local stock markets). In all, the property sector accounts for around a third of China's GDP [1].

The Chinese property market of today

New home prices in China fell by 4.5% in the year to June 2024, hitting the lowest level since June 2015. Property investment fell 10.2 percent in the first seven months of 2024. Property prices are projected to continue to drag so long as the oversupply of properties persists.

Private developers remain in financial distress. Operating income for private developers has halved since 2019, based on the financial reports of 44 Mainland China-listed developers. Collectively listed private developers reported cash on hand that was RMB 1.1 trillion less than their short-term liabilities in 2023, while state-owned developers were also seeing their surplus shrink. In some cases, private developers’ earnings were not enough to cover maturing debt instruments. In April 2024 China’s largest private developer, Country Garden, avoided default by winning approval to push back payments on three RMB bonds. While the most troubled private developers have already defaulted, the remainder must still service debt as their existing property portfolios drop in value and amid a quiet buyers’ market for new properties [2].

Developers are increasingly retreating from third and fourth-tier cities, focusing their shrinking investments on first and second-tier cities where income margins and consumer demand are more dependable. There remain a few localities that buck the downward trend, a prime example being Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province. Chengdu has a growing population, established industries, and a reputation as a lifestyle city, which has attracted internal migration from other cities in China. Chengdu has had consistent price growth, the average price/sqm growing 157 percent from 6,536 RMB (NZ$1,497) in 2014 to 16,185 (NZ$3,851) in 2022.

Land sales for property development are the largest non-tax revenue source for local government, so the property downturn also represents a significant economic and political challenge at the local level. Total revenue from land sales has fallen 36 percent from a peak of 8.71 trillion RMB (NZ$2 trillion) in 2021 to 5.54 trillion (NZ$1.3 trillion) in 2023. With rapid declines in land revenue, provincial governments have taken measures, slashing budgets, cutting staff, increasing tax enforcement, while becoming more reliant on transfer payments from central government.

President Xi Jinping famously stated at the 19th Party Conference in 2017 that “houses are for living in, not speculation”. It was in that year that skyrocketing property prices, driven by speculation, were seen to make homeownership a difficult prospect for ordinary citizens – especially younger people. This in turn became a symbol of the increasing concentration of wealth in Chinese society. Access to affordable housing remains a challenge today, particularly in tier one cities.

In May 2024, Beijing announced a set of policy measures to support the property sector. This was seen as the first serious effort to stem the property sector’s vulnerabilities. This included demand side support: lowering mortgage rate and minimum downpayment ratios, plus fewer housing purchase restrictions; and supply side support: a 300 billion yuan (NZ$67 billion) ‘relending facility’ to fund state purchases (by SOEs) of unsold housing inventory [3], and to create a whitelist of solvent private property developers prioritised for greater access to bank loans. Taken together, this policy support aimed to stabilise property prices and improve private developers’ access to cash.

This was followed up by a CNY 1 trillion (~NZ$ 235 million) package of monetary stimulus announced in September 2024, focused on shoring up China’s property market and generating economic activity. The package cut interest rates, lowered capital requirements for commercial banks and reduced mortgage rates.

Early signs suggested this rescue plan had been slow to fire, with only 24.7 billion yuan or 12 percent of the relending facility having been disbursed to SOEs. SOEs have not taken the funds to purchase unsold property in an environment where the borrowing rate on those funds is greater than possible rents SOEs could charge. The slow uptake of the relending facility means it has not significantly reduced total property stock or improved the finances of property developers who struggle to sell properties in market.

However, by October 2024 housing sentiment had improved, with a recovery shown in some economic measures. In October, home sales by value only fell 0.2 percent yoy, compared to a 16.5 percent drop the month before. Developer funding, inventories, and completed floor space all improved from the previous month. However, the overall picture remains challenging, with real estate investment falling 12 percent in October, the fastest decline this year. New construction starts also fell at the fastest rate this year.

China’s vision for the property market of tomorrow

From 15-18 July 2024, China held its Third Plenum – a five-yearly meeting that sets out the ‘economic tone’ for Beijing’s policy agenda. In its resolution document, the Party stated its intention to “establish a housing system that supports rentals and purchases and fosters a new development model for the real estate sector…[with] reforms to change the way real estate development is financed.” In other words, Beijing would balance the nearer term stabilisation of the property market with longer-term structural reform of the sector.

The tone set by the Third Plenum remains consistent with the policy direction set out by the “Three Red Lines Policy” in 2020: appropriately regulating the property market and gradually defusing systemic financial risk. Authorities have shown their willingness for a strong market correction, tolerating three years of decline in the property market and several defaults from private developers without major bail outs. The cost of this remains depressed confidence in new builds and lower consumer consumption.

At a macro level, the property sector reforms represent an example of the Chinese Government seeking to affect a reallocation of resources in the economy. President Xi’s emphasis is on “New Quality Productive Forces” or creating new sources of productivity by developing emerging and future-oriented industries, investing in manufacturing capability, strengthening industrial supply chains, and promoting the digital economy.

Property downturn depresses Chinese household consumption

The property market decline of the last three years opened up a large gap in aggregate demand [4] in the economy. The property sector and related sectors of construction and furniture-making are significant employers, consumers of goods and services, and sinks for investment in China’s economy. Even with the success of new areas of economic activity, such as electric vehicles, gains in the manufacturing sector have not fully offset the significant slack in the broader economy left behind by the shrinking property market.

The property market has weakened consumer confidence and dampened Chinese household consumption. China’s market is large, and different sectors and regions have differing trajectories, but overall Chinese households appear reluctant to spend due to uncertainty over their economic prospects, with a key source of economic pessimism the depressed property market. Chinese households continued their mortgage payments while their property assets depreciated (perpetuating even further a high savings/low interest rate environment). Other negative economic signals weighing down consumption include: slowing income growth in 2024 [5], 5.4 percent growth in H1 2024, compared to 6.5 percent in H1 2023; and lower labour utilisation rates including persistently high youth unemployment, which reached 17.1% in July 2024 compared to average urban unemployment rate of 5.2% over the same period.

China’s retail growth slowed in Q2 to a 2.7 percent year on year increase (down from 4.7 percent in Q1). In the month of June, China recorded 2 percent year on year retail growth – the lowest rate since 2022. This modest growth is in contrast to the rapid growth experienced for most of the period since 2000.

Non-Sector Specific Impacts on New Zealand Exports

The non-sector specific impact results from consumers seeking greater value and moderated high price expectations around some New Zealand exports. To remain competitive in a low demand environment for discretionary items, New Zealand firms have needed to lower prices. This shaves export revenue for New Zealand firms in the China market .

While consumption does not look likely to rise markedly in the short-term, economists see the low domestic demand to be cyclical in nature – meaning eventually consumption will recover. For this to occur, economic sentiment needs to fundamentally brighten and very high savings rates moderate. Commentators assess that the bottoming out of the property market – the stabilisation of house prices – as a key economic signal to restore a degree of confidence in the China’s economic prospects. While forecasting the highs and lows of markets is a fraught business, the current consensus appears to be that 2026 may be the year of house price stabilisation.

Sector Specific Impacts

The impact of sector-specific impacts on New Zealand exports have been felt primarily by the forestry industry. Other exporting sectors involved in China’s property and construction industry include architectural design, for example Architecture Van Brandenberg’s design of the Marisfrolg Campus in Shenzhen. The impact of the property downturn in this area remains to be seen – significant one-off projects may be comparatively less affected, for example.

China remains New Zealand’s most significant market for logs. In the year to June 2024, China took 92 percent of New Zealand log exports. However, China’s total log imports have consistently decreased year-on-year since the onset of the property downturn in 2021. However, impacts on imports of New Zealand logs from the property slump have not always been linear. New Zealand softwood exports actually grew 5 percent in the year to June 2024. The price point, flexibility of end-use, and efficient supply chain of New Zealand Radiata Pinus have buttressed the competitiveness of New Zealand log exports in China at the retail level when other international suppliers have struggled

China is New Zealand’s most important export market for forestry products, taking 92 percent of New Zealand log exports, worth NZ1.87 billion in the year to date through June 2024[6]. New Zealand is also China’s top source of logs, providing 35 percent of China’s total log imports in YTD June – far ahead of the US at second place with 13 percent (see Table 1).

China’s Import of Logs to YTD June 2024

| Rank | Trade Partner | Value (NZD) |

|---|---|---|

| ... | China total imports | 5,374,847,146 |

| 1 | New Zealand | 1,874,422,771 |

| 2 | United States | 715,652,182 |

| 3 | Papua New Guinea | 383,400,829 |

| 4 | Solomon Islands | 275,527,566 |

| 5 | Germany | 241,055,406 |

| 6 | Russia | 201,970,678 |

| 7 | Canada | 186,805,461 |

| 8 | France | 175,033,078 |

| 9 | Japan | 138,826,830 |

| 10 | Poland | 113,622,641 |

New Zealand is even more dominant in the subcategory of softwood, where we supplied 69 percent of China’s softwood in YTD June 2024 [7]. Pinus Radiata, a softwood, is typically exported to China as unprocessed logs, where it is then processed into furniture or panel products (e.g. laminated veneer lumber – an engineered wood product used in construction for non-structural purposes, including trusses, planks and rafters), or for use in the construction sector.

In the furniture-marking sector, New Zealand logs are used to produce furniture destined for both China’s domestic market and export markets. Given these sectors’ reliance on the property market, the current property downturn has weakened economic activity in these sectors – and by extension, impacted on China’s demand for logs.

In a 2015 study, it was estimated that 47 percent of New Zealand logs were used in construction lumber and plywood [8]. On Chinese construction sites, this wood was used in concrete-casting – a technique used in 80% of China’s multi-story builds [9].

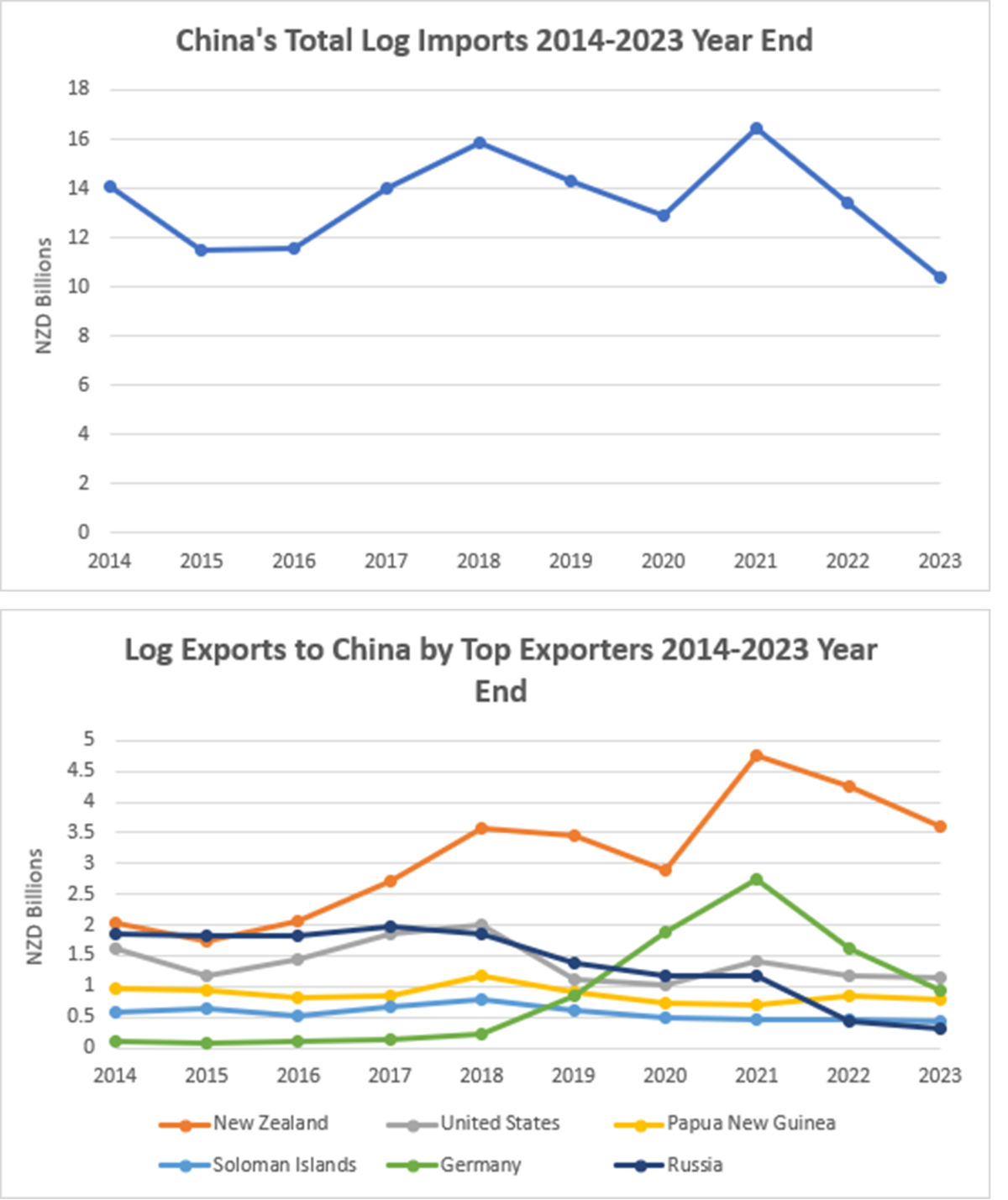

Since the onset of the property crisis in 2021, China’s total imports of logs have decreased, falling by 36% from 2021-2023 (from NZ$16.4 billion in 2021 to NZ$10.3 billion in 2023 – see figure 1a). This downward trend was observed in the exports of logs to China of all major suppliers. At a macro level the low demand from China’s construction sector, and other closely related sectors (e.g. furniture-making), has placed downward pressure on log prices.

Figure 1b: Logs Exporters to China by Top Exporters 2014-2023 (exports denoted in NZD and use YE figures from GTA). New Zealand's profile of exports over the 2014-2023 largely follows the trend of China's total of imports of logs. German logs have seen a larger drop-off than New Zealand exports since the property slump began in 2021. Russian log exports to China dropped in 2022 following the introduction of their ban on log exports.

Despite significant exposure to the China market, the impact of the property downturn on New Zealand log exports has not been uniform. Interestingly, despite the troubles of the property sector, New Zealand’s log exports have showed resilience. While the total log exports to China in 2023 (NZ$3.6 billion) was 24 percent smaller than its peak in 2021, 2023 levels were equivalent to 2018 levels (NZ$3.5 billion), which itself was another peak in recent market history). Against a downward trend in China’s total log imports, New Zealand’s soft log exports to China actually grew 5 percent year on year in the YTD June 2024. New Zealand soft logs have bucked the overall negative trend in the market through strong retail performance.

New Zealand’s Pinus Radiata retail competitiveness has been buttressed by a few key attributes:

Price: In the depressed property market, developers and closely related industries (e.g. furniture makers) remain sensitive to price. In 2023 the average price of New Zealand pine (NZ$198/m3) was cheaper than spruce or hardwoods from Germany and the US (NZ$326/m3 and $243/m3 respectively) [10]. This has kept New Zealand logs attractive in a weak market.

End-use flexibility: With a lower price point, New Zealand pine is used for a variety of inexpensive end-uses, such as packaging, forklifts pallets and concrete casting form wood. The broad range of end-uses meant Chinese log importers have a wider range of downstream buyers for New Zealand pine than some competitors.

Reliable supply chain: The efficient supply chain in New Zealand forestry plantations to Chinese ports was another key strength of New Zealand pine [11]. This was underscored during COVID-19 pandemic, where amid border closures, New Zealand’s forestry sector was quick to respond to China’s COVID-related border requirements. This was facilitated by the long-standing relationships fostered between New Zealand exporters and Chinese importers. New Zealand exporters also benefitted from New Zealand’s COVID-free status at the time.

External events have also played a role in the relative success of New Zealand logs exports. Russian soft logs are a comparable product to New Zealand pine due to its lower price point, but since a Russian ban on log exports in 2022 [12], Russian log exports to China have decreased (At the same time, Russian sawn timber exports rose, which competed with New Zealand’s sawn timber exports). German logs have also ceded market share, due to unfavourable weather conditions and pest infestations impacting export volumes (as well as the higher price of German logs). Other competitors such as the US have seen redirected log use to their domestic construction industry.

Future market factors for forestry exports

The current property slump has been a hard market demand correction, meaning that while demand for logs will eventually stabilise, it is likely to do so at a level lower than the heights of 2020-2021.

The long-time horizon in the forestry sector (the time for trees to mature) requires long term planning. In 2030 a large number of Pinus Radiata will come to maturation. A lower price could make New Zealand logs more competitive in the Chinese market, but log export revenues would be less. (Alternatively, if global prices are deemed too low, New Zealand forestry companies have the option to delay harvest and manage supply until prices recover).

China is a big market and there will always be construction and demand for logs. But demand can fluctuate, as does supply. The biggest challenges are when high supply coincides with low demand – a scenario made more likely as China sought to decrease the role of property in the overall economy. Amid challenging China market conditions and risk associated with high market exposure, New Zealand log exporters have so far demonstrated their ability to compete successfully at the retail level.

Background: The making the China's modern property market

- Since the 1990s, Chinese property prices have mostly seen sustained growth [13]. Chinese households and property developers alike consequently have come to see property as a low-risk high-return investment where substantial family savings could be invested. China, with many highly solvent cash buyers, developed a pre-sale system for commercial housing, whereby property developers sold unconstructed or incomplete homes and used that capital raised to fund new projects – a continuous cycle of leveraging deposits into debt to fund large new projects. In this system, developers pursued an aggressive business strategy: ‘high turnover (of properties), high gross profit, high leverage.’ This high debt-approach was sustained by strong new demand from Chinese households (investors and owner-occupiers) who grew their wealth through property.

- The expectation of a continually growing real estate market has eventually resulted in a property bubble and major debt issues. The average property price in China rose increased from 2,063 yuan (NZ$468) per square metre in 1998 to 10,139 yuan (NZ$2,240) per square metre in 2021. The upward trajectory of the market supported the growth of private property behemoths. These companies, such as China Evergrande and Country Garden, financed huge debt to expand their development portfolios. This led to an excess supply of property and a market exposed to a potential crash in confidence. The more the banks lent to property developers the more vulnerable they became to a downturn in the property market – and authorities became increasingly concerned.

- In late 2020 China announced the ‘Three Red Lines Policy’ – to measure and mitigate overleveraging by setting out three specific criteria around debt ratios [14]. The policy created a benchmark of financial fitness that developers needed to meet before banks would lend to them. This also enabled authorities to gain information on the level of debt held by developers. Separately, provincial governments tightened lending requirements for consumers (e.g. increasing required deposits for mortgages).

- The Three Red Lines Policy was successful in limiting lending to private developers with excessive debt, but it created a liquidity problem (access to cash) for some developers. Without new or rolled over bank loans, some private developers lacked sufficient cash to meet existing debt requirements, or to complete housing projects. Buyers of pre-sale projects found they owned incomplete houses or empty plots, which tanked consumer confidence in real estate. Demand fell further as COVID-19 and its lock downs continued, which stemmed the flow of cash from pre-sales homes.

- One of China’s largest private developers, China Evergrande, defaulted on US$1.2 billion (NZ $1.9 billion) in offshore bonds in December 2021. This was the start of several private property developer defaults and by 2023 two-thirds of China’s top fifty major private builders had defaulted on a debt repayment [15]. In January 2024, the Hong Kong High Court ordered Evergrande to be liquidated after the company failed to present a viable restructuring plan.

References:

[1] Estimates can vary. Some commentators put this as high as 30-40 percent when second order/indirect effects are considered.

[2] Surprisingly the market for existing property remains relatively strong, with record sales in 2023 according to research by Bank of China economist Xu Gao.

[3] Under the relending programme, the China’s central bank committed to providing up to 300 billion yuan in funds, which banks can use to support up to 60 percent of the principal of their loans, meaning it could generate a total of 500 billion yuan in lending.

[4] Aggregate demand: total amount of demand for all finished goods and services produced in an economy.

[5] Employees in some sectors were facing salary cuts, especially in finance and local government.

[6] Data from Global Trade Atlas, HS Code 4403 (which includes both hard and soft logs).

[7] Data from Forestry Economic Adviser (a forestry analytics and consultancy firm).

[8] Material flow and end-uses of harvested wood products produced from New Zealand log exports. Manley, B. and Evison, D.C. (2016)

[9] Discussions About Utilization and Development of Construction Formwork. Pearl River Modern Construction Cai, S. and Zhang, J. (1998).

[10] Data from the General Administration of Customs China (GACC).

[11] The New Zealand – China Log Export Market: An Investigation of Supply Chain Integrity, Scion (2016).

[12] On January 1, 2022, Russia introduced a ban on the export of logs restrictions on the export of oak, beech, and ash logs in January 2022.

[13] In 2014, China’s property sector experienced a downturn, but prices recovered within six months.

[14] The ‘Three Red Lines Policy’ sets the following criteria for lending: 1) Liabilities to assets ratio must be less than 70 percent; 2) Net debt to equity ratio must be less than 100 percent; and 3) Cash to short-term borrowings ratio must be more than 1.

[15] According to data compiled by Bloomberg(external link).

This article is a re-post from the MFAT Briefing, here.

4 Comments

Nominal A grade sawlog price is the same today as 1992. If that a strength I'd hate to see weakness-especially when the kiwi fuel user is pouring billions into the pine carbon scam.

92% of our log market goes to 1 country??? Holy F…. Three words spring to mind. Eggs. One. Basket.

how long can they delay harvest for?

Many years if you don't need any cashflow

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.