In my recent article on methane, criticisms I made of the proposed GWP* metric, pronounced ‘GWP-star’, stirred up responses from some of my agricultural friends and colleagues. Many farmers and also important farmer organisations would like to see GWP* used as the methane accounting metric. I received some long emails setting out where they thought I had gone wrong.

My response here is first to emphasise a point I have made many times: a prosperous agriculture is fundamental to New Zealand’s economic future. Primary industries are what pays for the majority of our imports. So, we have to get things right.

My second point is to acknowledge that there are sound arguments why the concept of carbon dioxide equivalence (CO2e), at least as currently used with the metric GWP100, is seriously flawed. But it is important to focus on proposals that will stand widespread scrutiny, and not live in an echo chamber.

The key argument put forward for GWP* to replace the widely used GWP100 (without the star), is that it accounts more accurately for the warming caused by methane. But the answer is not quite as straight forward as many of my friends think.

If it is just a case of measuring the outgoing radiation that is blocked by new methane emissions, in comparison to outgoing radiation that is blocked by new carbon dioxide emissions, then the existing GWP (without the star) can measure that appropriately, within the limits of known science. However, there is a caveat that the time horizon over which the comparison is undertaken is of fundamental importance.

Conventionally, this has been on a 100-year horizon (GWP100), which captures more than 99 percent of the methane heating units, but captures only a small proportion of long-lived carbon dioxide emissions. So, the GWP100 screws the scrum by ignoring all of the effects of long-lived carbon dioxide that will occur thereafter. That assumes, of course, that current society has a responsibility to leave behind a liveable climate that goes well beyond 100 years.

My own value judgement is that we would be better to use a 500-year (GWP500) basis for comparisons, thereby recognising the long-lived effects of carbon dioxide. By doing so, we would not be reducing the assessed value of the methane’s radiation-blocking effect, but we would be acknowledging that currently accepted science says that carbon dioxide lasts much more than 100 years. The numbers for GWP500 are set out in the IPCC AR6 document as laid out in my last article.

The opposing perspective of some of my friends is ‘Ah, but this is just the emissions effect and not the warming’. To which my response is that it all depends on how you measure the warming. Don’t get taken in by the notion that new methane emissions are benign.

The way I like to explain it is to get people to think of a ‘methane cloud’. We cannot actually see the cloud, because methane is colourless and has no smell. But there it is, up in the sky, and also all around us. It is a consequence of historical emissions. It is close on three times the size of the global methane cloud 150 years ago, although most of that increase has nothing to do with agriculture.

The currently accepted science is that methane has an atmospheric lifetime of around 12 years, or more precisely 11.8 years as recorded in the IPCC’s AR6 report. But this does not mean that all the methane disappears over 11.8 years. Rather, it means that half of the radiation-blocking effects occur in the first 11.8 years. It also means that 75 percent of the radiation-blocking effects will occur within 23.6 years, and about 88 percent will have occurred in the first 35 years.

For those who are mathematically focused, the decay is considered to be a first-order exponential decay function with a consequent long tail. For those who are not mathematically focused, don’t worry. Just accept that only half of the warming effects occur within the first 12 years.

Now, where does this all fit in within the GWP* effect?

The answer is that when claims are made that further methane emissions will not cause the temperature to further increase, referred to as ‘no warming’, the claimants are saying that these new emissions will do no more than balance out the ongoing decay of historical emissions.

The scientists who developed the GWP* equation have not said that new methane emissions are benign. But they have said that by their calculations, which do include some further assumptions, that as long as ‘global’ methane emissions reduce by 0.33 percent per annum, then by 2050 new emissions would be in balance with the decay of historical emissions. Note that this is on a global basis. Other sources have come up with somewhat higher figures and a clear consensus has yet to emerge.

What the physicists who developed GWP* have not considered is how these concepts could be applied at the country level or at the level of individual businesses. That is not where their expertise lies. Moving from a rugby analogy to a cricket analogy, it is at the country and individual business levels where the wicket gets real sticky.

There is a very nice 2022 exposition developed by authors Rugelj and Schleussner and published in the journal Environmental Research Letters that illustrates the sticky wicket. They develop the example of three young farmers, called Abraham, Bethany and Christopher. Each of them has 10 cows and each produces the same amount of milk. I draw on that example below.

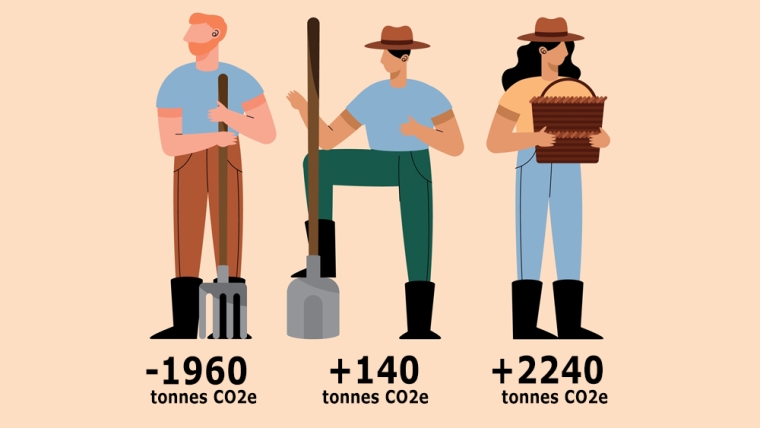

Farmer Abraham inherited his farm and the 10 cows from this grandfather, who had farmed that way for more than 20 years. Farmer Bethany came from a poor family with no cows but managed to secure a loan to buy 10 cows. Farmer Christopher inherited both land and 20 cows from his grandfather who had farmed those 20 cows for many years, but Christopher quickly reduced the cow numbers to 10 to fit in with his other activities. Over the next 20-year period they each produce the same amount of milk from their ten cows and each farm emits one tonne of methane per year. However, using GWP*, Abraham is assessed as producing 140 tonnes of CO2e over 20 years of farming, whereas Bethany produces 2240 tonnes of CO2e and Christopher is assessed as producing a negative 1960 tonnes of CO2e.

How is it that all of these farms are assessed differently under GWP* for the next 20 years just because they had different grandfathers? Well, GWP* gives Christopher a huge credit for the decline in his methane cloud relative to his grandfather, whereas poor Bethany has no prior methane cloud on which to call for credits. Abraham has enough methane decay in his cloud to almost balance his ongoing emissions so his assessed liability is very small.

Generalising to the underlying principle of ‘grandfathering’ as it applies to environmental issues, it refers to situations where previous actions of a business or country give rights to continue those actions into the future on a preferential basis. It shuts the door on the ‘Bethanys’ of this world and leaves the door wide open for the Christophers to maintain existing behaviours and do so profitably. That notion, of ‘to those who have shall be given’, goes very much against the Paris Agreement.

Well, that is enough on GWP* for now, but the issue is not going to go away. I simply say to my farming friends that it is best to fight battles that are winnable. GWP* provides useful insights as to the global temperature effects of methane taking into account both the warming from the current emissions and the decay from the historical emissions.

It can also highlight at the global level that if global warming really is the threat that many consider it to be, then by far the most effort has to be on reducing CO2 rather than methane. But it does not provide a basis for working out how each country and business therein should bear the costs.

So, what are the other arguments that methane decision-makers need to be aware of?

In my opinion, the most interesting new science is a paper published in Nature Geoscience in 2023 demonstrating how current science has largely ignored the absorption by methane of UV energy from the sun.

When the effects of this absorption in the troposphere are included, their modelling indicates, somewhat counterintuitively, that within an atmospheric-systems framework that clouds increase such that less UV rays reach earth. The effect is estimated to reduce the overall radiation-forcing caused by methane by about 30 percent.

I am not aware of any reporting in the New Zealand media of this research. However, the international science community has reacted positively to these findings, while recognising that they need to be confirmed using other models before a high confidence level is placed in the results.

I have said enough for this article, but I still have not got to the end of the story. In particular I have not laid out a path to a future that protects New Zealand’s primary-industry led economy and does so in a way that will be internationally acceptable. That will be the next article before moving on to issues other than methane.

*Keith Woodford was Professor of Farm Management and Agribusiness at Lincoln University for 15 years through to 2015. He is now Principal Consultant at AgriFood Systems Ltd. You can contact him directly here.

21 Comments

Keith,

"It can also highlight at the global level that if global warming really is the threat that many consider it to be, then by far the most effort has to be on reducing CO2 rather than methane"

When I raised this issue with Professor Renwick, whom you will know is one our leading climate scientists, he said this in his reply; 'This country's carbon dioxide emissions are considerably more important than our methane emissions, as reflected in our zero carbon legislation'.

I have no farming connections, but like you, I recognise their economic importance to this country; a country with very significant economic issues to deal with.

linklater01

That is an important statement from Professor Renwick.

Unfortunately the the much more regularly heard statement that half of New Zealand's emissions comes from agriculture, which we hear so often in the media, give a different impression to those who are not properly informed.

KeithW

I see cultured meats displacing live stock and likely its only a matter of time before milk comes from a bioreactor. NZ should be getting in on these advancements...bonus is it will free up land...Israel has just approved Aleph...and its only a matter of time before the rest of the world changes the marketplace. Traditional methods are under attack . Might be better if NZ industry spent more on the alternatives than battling the traditional model?

If cultured meats do become mainstream it is unlikely that New Zealand would be a major producer of such food. It is a field in which New Zealand has no comparative advantage.

KeithW

Why would NZ get into cultured meat and milk, certainly a waste of time exporting using tonnes of CO2 to get it to market. Just make it at market.

Been waiting decades now hearing it's on the way, still waiting.

Thankfully, as I am a farmer, no one wants to eat that rubbish. It seems to be missing the impt ingredients that pass as food, ie vitamins and minerals, and tragically contains stuff you dont want in your food, ie nano plastics, antibiotics, chemical additives...blah blah...eww

These days I have to avoid most of the supermarket as emulsifiers, flavourings such as MSG, crazy new sugars and stabilisers are rather poisonous to me. From googling I seem to be in very good company. We are being poisoned already from those middle supermarket aisles. God forbid that meat and milk become a hodgepodge of all the above ingredients as well.

Did Abraham, Bethany and Christopher forefathers wipe out 60 million bison and replace them with 90 million cattle? Did the "methane cloud" notice?

While we are debating the 3 farmers debt, none of them actually reduce their methane output.

Pretty much illustrative of the world's actions. Figuring out who is worst than us, and not getting on with doing anything.

The less we do now,the more our children have to do.although it is looking more and more likely it's going to come to a head in our lifetime.

Total cattle numbers have remained pretty static in nz over the last 50 years between 8 and 10 million. Sheep numbers have dropped from 70 million (early 1980s) to 20 something million

Methane is a short lived gas and emissions from nz livestock are probably reducing.

Maybe we need to cut the crap (yes its a pun) and focus on carbon dioxide oxide.

FlyingHigh,

The number of beef cattle has stabilised around 3.9 million. Beef cattle numbers, which peaked at 6.3 million in the 1970s, totalled 3.5 million in 2016, a historic low. More recently the number has stabilised and totalled 3.9 million in both 2019 and June 2022.

Greenies seem to make an issue of dairy cow numbers increasing and chasing the white gold. However as you point out, over the same time frame the number of beefies has equally dropped.

If include sheep numbers, the total number of methane producing ruminant livestock has declined massively.

I dont know why we have the discussion about taxing methane emissions, it's a short lived gas and scientists say there is no climate effect from methane. The taxing of methane was simply grandstanding from the labour benches so they could say they were "world leading"

scientists say there is no climate effect from methane

Reputable ones don't.

Maybe because of more use of Dairy beef , resulting in less pure beef breeding stock required?

Here is the methane breakdown for agriculture and the trend.

https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/new-zealands-greenhouse-gas-emissi…

KeithW

Figures from 2020... why are they so far behind

I would also question the livestock component for the reasons given. Sheep numbers are one third of 1980s numbers and cattle (beef and dairy) are largely unchanged. There should maybe be an independent audit.

"...Even more strikingly, if an individual herd’s methane emissions are falling by one third of one percent per year (that’s 7/2100, so the two terms cancel out) – which the farmers I met seemed confident could be achieved with a combination of good husbandry, feed additives and perhaps vaccines in the longer term – then that herd is no longer adding to global warming."

https://newsroom.co.nz/2019/03/28/a-climate-neutral-nz-yes-its-possible/

Who cares about livestock when we have a 6 million km2 continental shift sucking up 20 tonne CO2-e/km2/annum through CaCO3 deposition.

"...New Zealand was a net CO2 sink of −38.6 ± 13.4 TgC yr−1."

A Comprehensive Assessment of Anthropogenic and Natural Sources and Sinks of Australasia's Carbon Budget

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2023GB007845

Natural carbon sinks aren't apportioned on a country-by-country basis.

For the purposes of climate change it doesn't matter who is producing emissions.

Thanks Keith. At least we have stopped growing our emissions. Lets see what happens in the next 3 years.

Great analogies Keith - No easy answers here but it reinforces we need to put most of the focus on reducing CO2 - methane will need something but there is a lot of work to decide how we set the parameters for that - it reminds me of all the grandparenting arguments that have been going on for decades on other subjects here. No one wants to loose anything.

Some comments here still cant accept that something in some form will have to happen - its a mater of degree and who it affects.

An adaptation of this idea could go along way towards helping farm profitability, and lowering their net emissions (or raising their net carbon sinking, depending on which scenario above is chosen).

https://das-energy.com/en/products/greenhousemodule.

Grazing already happens under solar farms , Usually on flat ground , i see no reason why it can't also be on north facing hills.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.