One of the global fallouts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been the highlighting of just who vulnerable world food security can be to disruption.

Wheat or at least grains are a staple part of a balanced diet as well as being a major component of domestic animal diets. They also have the benefit of being able to be stored and relative to other food types can be grown relatively cheaply. However, depending upon where (in this case) wheat is grown there is a large variation in both production and cost of production.

Latterly both of these factors have come under pressure also partly although not solely due to the Ukrainian conflict with fuel and fertiliser costs ratcheting up considerably. Due to the recent impact of the conflict published data is not going to capture all the recent increases in costs however given the widespread nature of the cost increases it can be expected that the same or at least similar relativity between regions will remain.

Wheat, which has been around for over 8,000 years and grown on over 240 million hectares, is able to be grown in most hemispheres of the planet with large volumes being grown in both North and South Americas, East and Western Europe, Australia (and New Zealand) the Indian sub-continent, China and Africa. However, despite the widespread nature of where wheat is grown there are still plenty of countries which are largely, in some cases, totally, reliant of importing wheat to meet their needs.

The top 10 wheat producing countries by volume are:

However, if the EU were combined as one block, they would be second only to China with 126,658,950 tons.

It is also worth noting that although corn is the most produced grain crop globally, wheat is the most traded across borders and 30% of that is made up of Russia’s and Ukraine’s. (An aside of some interest is given how world trade has been disrupted by the Ukraine conflict, New Zealand makes up approximately 35% of world traded dairy products. This shows how vulnerable world dairy demand is to the vagaries of New Zealand production and if there was a sharp drop-off in production here it would have global ramifications).

Yields vary considerably across different regions with rates going from 1.5 tonnes per hectare or less in developing countries often affected by drought, although Australia at the national level also is around only 2 tonnes per hectare with New Zealand at 10 tonnes on the top of the pile.

As can be seen when comparing the top 18 nations on productivity only China and the EU as a block feature on both tables.

The other issue that emerged was how little profitability is achieved by any of the major producing countries. A study by Purdue University (USA) showed that on average over the 5 years from 2016 – 2020 the majority of farms studied (at the national level) showed that the wheat enterprises operated at a loss for at least several years. It does not necessarily mean that the farms on the whole were not profitable with other enterprises ‘carrying’ the wheat losses.

The largest typical farm in the Ukraine had an average loss per hectare of US$100. Average losses per hectare for the typical farms in Australia, Saskatoon, Germany, North Dakota, and Kansas were $18, $18, $56, $55, and $103 per hectare, respectively, during the five-year period. The lowest economic profit during the five-year period for the typical farms was 2019 with an average loss of $80 per hectare. The average loss in 2020 was $79 per hectare. Average economic profit was positive for 2016, 2017, and 2018.

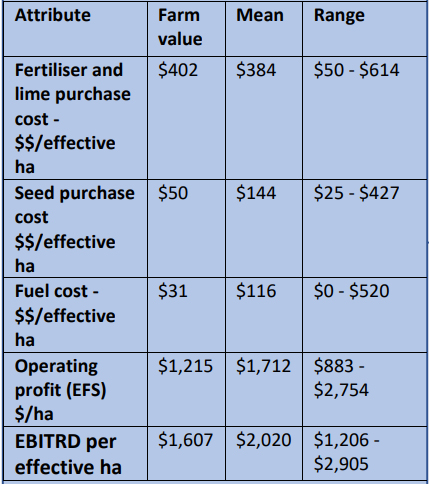

The situation in New Zealand while seemingly difficult to get an overall picture, an Autumn 2022 paper put out by FAR and based upon Manawatu farms in this case showed a more positive outlook for arable farms in general with a profit level of around $2,000 per hectare.

However, New Zealand blessed with rainfall and irrigation while seemingly as or more profitable per hectare than other countries has a greater range of land use options which may provide greater returns. There is of course the potential for this to change if all enterprises externalities were taken into account and costed in.

The EU in late March, aware of the spanner in the works the Russian invasion was/is having of world food trade and costs to consumers, agreed to subsidise its farmers to the tune of US$550 million to increase in particular wheat production.

On a positive note, it is now looking as though some resolution is being reached to enable wheat and other food stocks currently locked in Ukraine access to the Black Sea and out onto world markets.

In the meantime both costs to producers and consumers will skyrocket as fuel and fertiliser costs are increasingly still impacting upon returns to growers and hence onto consumers.

23 Comments

Don't eat meat or grains.

My, that doesn't leave much option..

Seems to me, if people talk of a strategic reserve of fuel etc, then we should grow enough millable wheat to cover our bread and other direct consumption. If it requires a subsidy, so be it.

Why should wheat production be subsidised ?

Subsidies just lead to bigger government, more taxes and less efficient production systems.

Consumers should pay enough to ensure all necessary food is produced in sufficient quantities or produce their own food.

Society’s will need to readjust it spending priorities and put food at the top of the list.

Food cost relative to house hold incomes has been to low for far to long.

Australia should be on the list they are expecting to produce 30-35 million tons in 2022 a bumper crop up the their normal 25 m tons ?

For a background summary to "the Green Revolution" lying behind the problems for the feeding of our projected 10 billion population I found this youtube clip informative and balanced https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GgHy8KQ4Ifg.

(As an aside . Particularly interested in the discussion of health issues related to the almost universal dwarf wheat we now consume - especially grateful to Keith Woodford for his comments on glutein based on his experience. Our personal experience also suggests that not only wheat variety but bread making process e.g. short cycle proving, may contribute to some of the issues.)

... " slow breads " , sourdough .... are far more digestible than modern factory quick turn around bread ... People suffering " wheat belly " should give sourdough loaves a trial ...

Also, Spelt wheat is a very old variety that is high in protein and low in gluten. Good for anyone with gut issues.

... yes ... question is : how many people as a % are actually diagnosed by a real doctor to be gluten intolerant , vs the % who've self diagnosed via Dr Google ... as far as I'm aware gluten is an essential protein for us , and the protein which gives breads their stretchy spring ...

Yes agree with both the above contributors suggesting sourdough and spelt - tried both with good results. We are also nutters so we make acorn flour from our Portuguese Oaks (quercus faginea) - and add about 50gm to our 450gm bread mix - works great. Another aside - we've also found A2 milk reduces gastric problems in our family. Thanks again Keith Woodford. For some years we lived in Mexico and part of that experience was better health from a maize based diet and locally produced fruit veg and meat. Self diagnosis? True Dr Google can be a hypochondriac tunnel but we take our health as our personal responsibility - don't lecture others and don't ignore our personal experience or our training. You pay your money if you are lucky enough to have it and make your choices.

I'm a big fan of adding unprocessed seeds & nuts into the diet ... rolled oats , brazil nuts , walnuts , pumpkin , linseed , chia , quinoa & sunflower seeds ... raw , no salt nor fat ... brilliant snacks ...

GBH,

I can assure you that gluten is not an essential protein.

Your are correct that it gives bread the 'stretchy spring'' and inherent lightness.

The best way to determine whether or not you might have a gluten intolerance is to remove wheat from the diet for a period of say 6 weeks. Then make a judgment in regard to your own digestive health, and also whether or not there is any change in inflammatory conditions. That can include various arthritis conditions and a range of auto- immune conditions. Digestive benefits can be assessed in just a few weeks (or even less) but auto-immune conditions might take a little longer.

Wheat-free diets tend to place emphasis on oats, rice and corn products. It is not hard to do. There are also a range of other grains that are fine. Sourdough can also have a role to play but best to initially keep away from it for those first six weeks ,then introduce it slowly and see what happens.

It is also not a bad idea to move to A2 milk, i.e. milk free of A1 beta casein - there are multiple brands available. The reason for this is that both gluten intolerance and intolerance to A1 beta-casein relate to the known fact that both gluten and A1 beta-casein release opioid fragments on digestion. This is very much an emerging field of science, in which I have some involvement. Here is a recent scientific paper I wrote, published (open access) in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Alternatively, go directly to https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/15/7911 for the paper.

KeithW

The problem more generally industrialised countries produce excess food supply which is exported while non-industrialised countries tend to have growing populations and rely on importing food.

Vertical farming may solve some of these problems , and enable significant food production within CBDs ...

Are we talking about lettuces, reputed to require more calories to consume than they contain, fed on liquids or grown on mulch imported from the Far East.

Ill pass thanks..

no we are noit talking about lettuces. I suppose the question is what do you grow to eat? Forget the theory. everyone who contribites to their food intake - whatever is a winner. Theoreticians don't matter.

Two of the input costs in growing wheat and farming in general are fuel and fertiliser. As NZ is part of the EU and USA and some other Western countries we cannot import Russian fertilser or fuel without incurring a 35% NZ tax on the imports.

India, Pakistan and probably a few others are importing discount oil and fertiliser from Russia.

The reason that wheat growing can be profitable in NZ is that the tyranny of distance means that it is expensive to ship wheat to NZ.

Hence the price of wheat in NZ is very high by international standards.

The same tyranny of distance plays a key part in making NZ-grown wheat non-competitive in international markets. That is highly unlikely to change.

KeithW

How much do we grow here per year Keith. Thanks in advance

I don't have that figure at hand, but most of the bread-wheat is imported, mainly from Australia.

Most of the grain that we grow is used for animal feed.

Arable farmers would like to see more bread-wheat grown in NZ but the flour manufacturers see things a little differently.

KeithW

New Zealand produces over 300,000 tonnes of wheat of which 70 to 100,000 tonnes are used by flour millers for bread and biscuit production, mostly in the South Island.

The remaining wheat is used for poultry, egg, dairy cow and pork production.

So enjoy your breakfast courtesy of the New Zealand arable farmer who helps produce bacon and eggs, pork sausages, butter on toast and milk for your coffee - all made in New Zealand.

Yes, except that most of the pork and bacon are imported

KeithW.

I remember been told by a 90 year old vegetarian to always toast bread, but i think her reasoning was to kill the yeast, not with gluten. Candida in the stomach is no fun , I can vouch for that .

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.