At the start of this week there was widespread coverage of research published by Dr Mike Joy et al on the impact dairying is having New Zealand’s waterways in particular in the Canterbury region.

I’ve never been a great fan of Mike Joy’s style. To me he lets his personal bias (anti-dairying) come to the fore a mite too much for my preference. Having said that, New Zealand needs people like him and Forest and Bird etc. to hold us to account and act on behalf of those that can’t - in this case, ecological systems.

The original research ‘paper’ is 25 pages and so takes a bit to digest. However, as dairying is such a critical component of the New Zealand economy, especially at the moment, and I’m living in the midst of it in Selwyn Council District in Canterbury, I felt a need to give the research a reasonable go at critiquing.

The research analyses the consumption of rainwater (green Water Footprint [WF]) and groundwater or surface water (blue WF) needed to dilute pollutants produced as a result of a product’s manufacture. In this case required to dilute by flushing the aquifer of nitrates.

There was a range of levels of dilution applied because, as we’re starting to have to accept, the WHO standard of 11.3mg/l is really questionable whether or not can be considered safe both for drinking and for ecological values.

The now well-known Danish study believes anything over 0.87mg/l of N greatly contributes to the incidence of colorectal cancer after long term exposure and even lower N levels at .44mg/l are the trigger level for impacting upon ecological values. The media focused heavily on the worse (or 'best', depending upon your world view) figure of the water required to dilute down to 0.87mg/l.

According to the study this was assessed at 1,150,000 litres. To get or stay within the WHO bounds of 11.3mg/l a lesser amount of 88,500 litres is required. In my view the researchers use of only dairy land’s area as the rainfall catchment was a flaw in the project as the aquifers in Canterbury are considered ‘unconstrained’ and so are a catchall of the all the water that falls on the plains and beyond.

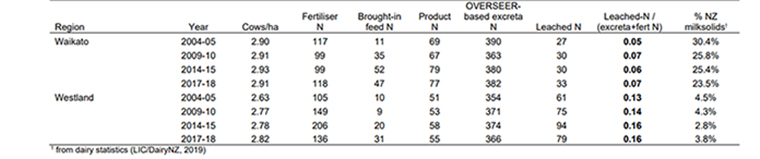

I did my figures on 3 million hectares (total Canterbury Plains area) with an average rainfall of 750ml per annum. My numbers for cows and milk volumes were very similar to theirs although I initially believed that their use of 69kgs of N leached per hectare was on the high side until I got a recent table from an MPI publication which reinforced that number. (See below with the “Leached N” being the number of interest).

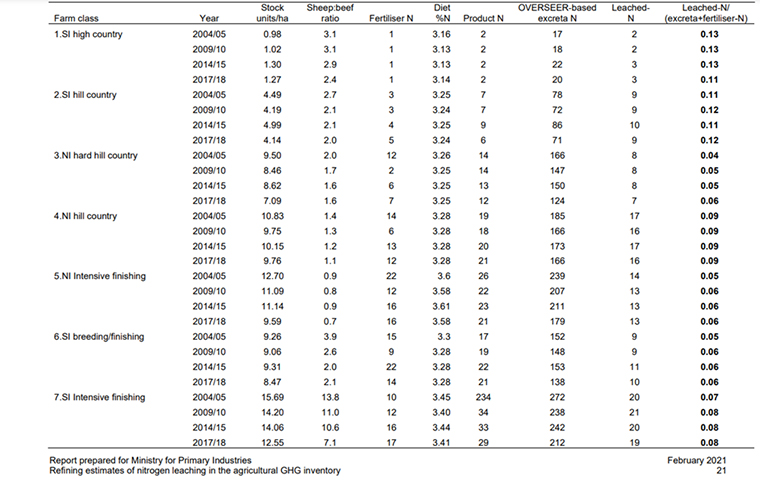

At this stage it is perhaps useful to look at other land-uses and N leaching from them. Below is the averages from sheep and beef farms.

Finally, arable crops over an average season.

What concerned me was that the latest dairying data used was 2018 and there seems to be little published information of what more recent data would like. A consultant at the cliff face of conducting Overseer© monitoring said he thought most Canterbury farms would fall into the 40-70kgs per ha of N leached to water. Not too far from the MPI and Mike Joy’s number.

Unfortunately, even using the 3 million hectare catchment figure didn’t do much to change the gist of the research. It provided 4,500 litres of water per litre of milk produced, still a long way from what is required to flush out the aquifers. As can be seen Westland dairy exceeds even Canterbury’s numbers, but with the higher rainfall, proximity to the ocean and lower population, it has avoided more intense scrutiny.

Canterbury has long recognised it has a major issue with water, as do most intensively farmed regions. The Regional Council (ECan) brought in stricter criteria to start to mitigate against the problem and rising public concerns back in 2010.

N levels were capped to the 2009-10 year which effectively stopped any more dairy conversions taking place unless the land already had a high N history or was part of a district irrigation scheme.

Last year nitrogen applications were capped at 190kgs per ha and farmers were required to adhere to best practice to work towards making dairying more sustainable.

Among all this, ECan brought the desired maximum level of nitrates in the aquifers drinking water down from 11.3mgs/l to 2.6mg/l (a compromise figure). Already many Canterbury wells are above this level and many in the public would like to see it lower still.

The Government is going to review the National Water Policy in 2023. Given the relatively short time frames since any (arguably) meaningful policy has had to influence water quality I can’t see much short-term change. The fact that it takes time for N to travel through the ‘soils’ to get to the aquifer where its impact can be measured does provide some breathing space for dairy farmers.

However, a summary in the latest Irrigation News magazine, of a paper published in Nature Journal Scientific Reports (August 2021), has found in New Zealand that it takes on average less than 5 years for nitrates “to travel from farm to river”. The range was from one to 12 years, with sloping land being the longest.

This time frame I believe is less than many in Canterbury have believed in the past and at this rate (5 years or less) we should be seeing improvements now or certainly soon.

The fact the farm per hectare rates of N leaching are still high (if improved) means that we are clinging to straws if we believe we are going to see any real improvement in the foreseeable future.

One of the frustrating things for those on the sidelines is the knowledge that there are systems which can be incorporated and have a large impact on nitrate leaching as Keith Woodford has highlighted several times, but despite record payouts there still appears little uptake. ECan has a part to play with more regular monitoring and publishing of data of the state of the Canterbury aquifers to keep a focus on what the real situation is, good or bad. At the moment what little information that comes out is thin and far between.

Mike Joy’s research concludes with a view that if something dramatic does not happen soon then ...

“Dairy farming will result in steady state nitrate concentrations on average of 21.3 mg NO3--N/L in groundwater originating from dairy farming areas in Canterbury, rendering much of it undrinkable. The groundwater drinking water supply of Christchurch, the second largest city in New Zealand, will also become significantly polluted with nitrate from dairy farming in the Waimakariri River catchment, and the current deep aquifer median nitrate concentrations of 0.3 mg NO3--N/L will rise to median concentrations of at least 4.7 mg NO3--N/L.”

I doubt it will get to these levels as a circuit breaker will need (have) to be applied before this stage but dairy farmers need to front foot this issue otherwise we will be seeing a wholesale land use change (again) in Canterbury.

The research article also highlights what is being experienced in the EU:

“In Canterbury the amount of nitrate leached to the environment more than doubled from 1990 to 2017 (Ministry for the Environment and Statistics New Zealand 2019). The average for dairy stocking rate for New Zealand in 2017-18 was 2.8 cows per hectares and for Canterbury 3.4 cows per hectare (LIC and DairyNZ 2018). This stocking rate is high compared to the rate of about one dairy cow per ha mandated by the European Union (EU) to protect freshwaters. EU member states are required to guarantee that the annual farm application of nitrogen, as animal manure, does not exceed 170 kg per hectare, equivalent to a stocking rate of one cow per ha (Mateo-Sagasta, Zadeh, and Turral 2018).”

Some thoughts from other sources and regions are;

Marnie Prickett of Choose Clean Water says, “It’s not a big ask to set a nitrate limit under one. Many regional councils already manage nitrate pollution to more stringent levels. Horizons Regional Council is managing to 0.44 mg/L, while Hawkes Bay Regional Council set their limit at 0.8 mg/L”.

“The Ministry for the Environment itself recommended last year that nitrates not be allowed to exceed 1 mg/L, as did the majority of the Science and Technical Advisory Group advising on the Fresh Water Standards.”

Dairy prices

Select chart tabs

43 Comments

Guy. I am in awe of yoyr ability to cut this down into such digestible form.

Well, there really is only one realistic solution, isn't there?

Wrong.

As Guy alludes, there are profitable dairy farming options that involve capture of nitrogen, and reaaplication where it is captured in plant growth.

Guy, Did I miss it, or was it not there, what is the concentration of nitrates in Christchurch drinking water ,now? Is it above or below the cancer trigger level of 0.44mg per litre,of the quoted Danish study?

Hi JimmyH

Finding clear info on Christchurch water is not an easy search. The best I could come up with (from CCC) was equivalent of 1mg/l (and no date attached??) The Danish study was at .87mg/l The .44mg/l refers to the start of ecological damage (going from memory here). WHO standard is 11.3mg/l but largely considered out of date. The lack of clear info goes back to my point that authorities need to do and publish more test results. Good or bad. This issue is becoming political and needs a light shone on it.

I too have been unable to find good data on the Nitrate-N levels in Christchurch water. If anyone has a published source, preferably from multiple bores and over time, then please let me know.

KeithW

Interesting Dutch article I came across yesterday:

In May 2019, the Council of State ruled the government’s strategy for reducing excess nitrogen was in breach of EU directives on protecting vulnerable habitats and that the way the release of nitrogen was being calculated when assessing construction project licences was questionable.

The court’s decision meant that the Netherlands had to develop new policies to reduce nitrogen-based pollution and that every activity which led to nitrogen being emitted, from building new homes to farming, needed a permit.

The ruling prompted a flurry of measures. Thousands of building projects were put on hold, threatening housing targets, the speed limit on all roads was reduced to 100 kph during the day and plans were drawn up to slash the size of the intensive farming sector.

‘Flanders in Belgium is in the same situation because environmentalists there went to court using the EU directive and called for a new strategy as well,’ says Leiden professor and nitrogen expert Jan Willem Erisman. ‘Both the rulings related to a European court decision in 2018 which said EU members have to protect vulnerable habitats and reduce nitrogen. So if German or French activists went to court, the situation would probably be the same there.’

https://www.dutchnews.nl/features/2022/06/whats-all-the-fuss-about-nitr…

Thanks for a balanced report.

There was a plan for the Canterbury plains to do managed aquifer recharge. This would have flushed the nitrates out as well as diluting them. The trial was very promising. But guess who opposed it? Mike Joy and the Greens.

Water Fools? - 'Recharging' Canterbury's aquifers | RNZ

So in Dr Joy's world view, only acceptable solution is to stop irrigation and dairying. Not a very balanced view.

Chris M

Reminds me of the quote recently ‘’ Putins useful fools” referencing the greens in Europe who ensured reliance on Russian gas & oil, we all now see the end result

Flush it to where???

Solarb, you really should learn your basic geology. It would flush it into the ocean, - and where all the sewage in Auckland and Wellington goes with its high levels of nitrates go.

According to this paper, increasing the level of nitrates in the ocean will increase the absorbing of CO2 - probably also increase fish stocks as well.

Yes, my education seems to be lacking, I thought dinosaurs were extinct.

No dinosaurs are not extinct. The scientific answer is that the birds are the direct descendants of some of the dinosaur species, the therapods. So you education is most definitely lacking.

The blog answer is that if actually reading all the scientific information and understanding it makes me a dinosaur, I'm happy to have that label. But that unscientific "knowledge" you seems to believe in puts you at a disadvantage, doesn't it?

So how does the flushed nitrates get from the aquifers to the infinite sea?

I think it's been pretty clear for years that diluting waste is not the answer, because we are reaching the limits of what even the seemingly vast oceans can take. Read the end of nature, ,1980's, or silent spring, 1970's.

I do agree the nitrate is a wasted resource, but believe the answer lies in balancing it out with other organic matter. Some carbon crops to incorporate into the soil for e.g, or a closer relationship between farm and forest. Before anyone brings up heavy metals, osier willows and other plants can absorb them.

solar - if you want to be credible, you need to stop asking dumb questions (even if rhetorical) that a minute of Google can answer

"So how does the flushed nitrates get from the aquifers to the infinite sea?" Even for confined aquifers, they have an outlet at the bottom - that is why there is a freshwater spring in the middle of Wellington Harbour from one of the Hutt aquifers. Depending on which gravel aquifer on the Canterbury plains you are looking at, the discharge point is some kilometres out in the ocean from the shore. From other work they have done, flow rates can be 11m/day even with a depleted table. Top it up more and flow rate is faster.

The dilution won't happen overnight, but it is happening. They probably only need to flush down to SH1. Below that road, there are other higher (which are the ones used) aquifers but they might be contaminated with nitrates from septic tanks. That is one of the things people don't want to talk about.

And there are no springs discharging into rivers?

If they are confined aquifers, generally no springs. Depends on the permeability of the aquitards. And depends on the hydrostatic gradient through the aquifers. For the springs on the Hinds, it looks like the springs were from the upper unconfined aquifer cause by water level lifting

The question is where will all the water come from to flush out (i.e. dilute) the nitrogen pollution

I see you couldn't even be bothered checking the link in this thread before commenting.

The technology has been tested for the past nine months, over a 3km2 plot of land near Ashburton. It has so far cost $750,000, with the bill being picked up by local councils and irrigation companies.

How often would this be required and does it involve trucking water in. The costs to date of quarter of a million dollars per 100 hectares is not sustainable IMO

Where will Canterbury dairy farmers get the water to flush out the aquifers because even Guy's check of the figures acknowledges it will take more water than Canterbury gets in rainfall.

Brendan - you seem to have no knowledge of the Canterbury Plains hydrology but it hasn't stopped you commenting. Ever heard of the Rangitata Diversion Race? You could do similar schemes for the Rakaia and Waimak, then just take water to a stilling lake, before it goes to the recharge system. Only take the water when flow is above say 300 cumecs would give plenty.

Chris - read the article. Guy didn't use the land area in dairy for his calcilations. He used all the rainwater in the whole water catchment area of "the Canterbury plains and beyond". That includes the headwaters of the major Canterbury rivers. There still is not enough water to dilute the amount of nitrogen being produced.

It would actually help Brendan if you took your own advice and read the own article. Did you note the sentence "I did my figures on 3 million hectares (total Canterbury Plains area) with an average rainfall of 750ml per annum. "? So he didn't use the recharge figures from the big rivers that come out of the foothills. That is where most of the aquifers that Christchurch uses are fed from, not plains rainfall. From memory it is south bank Waimak out by West Melton

For interest, I did the maths on ECan figures of the Rakaia above Rakaia Gorge. Average rainfall 2.4m/ year

Chris I trust Guy's and Mike Joy's figures over yours. You can of course write an article showing how you have found more hectares and more rainfall in Canterbury's watersheds and how these can be used to dilute nitrogen so that excess nitrogen in waterways and aquifers are remedied. It that can be achieved we would all be happy.

So what you really mean is you haven't got either the nous or maths skills to actually look up the numbers on the ECan site and do the calculation yourself. That is why disinformation happens. No independent checks.

Really - you are that certain your analysis is right while Guy Trafford and Mike Joy's are wrong?

And you do not think you should write-up your proposal officially.

Why is that? It would be really beneficial to solve this problem? Do you not agree?

"The research analyses the consumption of rainwater (green Water Footprint [WF]) and groundwater or surface water (blue WF) needed to dilute pollutants produced as a result of a product’s manufacture....This footprint is higher than many estimates for global milk production, and reveals that footprints are very dependent on inputs included in the analyses and on the water quality standards applied to the receiving water." Plant uptake and soil saturation is ignored in the abstract. Rather a large omission.

Mike Joy ignores that nitrate leaching is a natural process and that other factors come in to play other than “dilution”. Activists like Mike love to have non-standard scientific units like "footprints" so they can fill their footprint full of fudge factors to suit their narrative. The paper portrays that 100% of nitrate must be "diluted" and ignores major natural variables such as plant update and soil saturation. Though you would do that if you wanted a 11,000 litre headline for the MSM.

For those that want to get a better understanding of the principles and results, here is what appears to be the latest annual report

Hekeao/Hinds Managed Aquifer Recharge Trial: Year 4 update and next steps (hhwet.org.nz)

I note the scheme appears to have been a success as they want to both make it permanent and expand it. . From the ECAN Policy guidance document on aquifer recharge, they appear to support it.

"The identification and expansion of MAR opportunities within Canterbury has resulted in the need to develop policies and rules in the Land and Water Regional Plan (LWRP) that enable MAR to be utilised more widely, whilst providing adequate protections, particularly when contemplating developments ranging from a cluster of MAR site through to a larger catchment-wide Groundwater Replenishment Scheme."

And I note doing the maths, from the actual results the amount of water needed is orders of magnitude lower than Dr Joy's model. How surprising - not.

In the Risk Map of Nitrates in Canterburydocument put out by ECan, they make the following statement

"Nitrate nitrogen concentrations greater than about 3 mg/L are usually caused by human activities such as waste and effluent disposal, or leaching from normal farming activities (Nolan and Hitt, 2003; Daughney and Reeves, 2005). Nitrate that is not used up by plants can be flushed through the soil into shallow groundwater by rainfall or irrigation"

This would indicate, that even with no farming activity and a long flush, there will be nitrate levels in the natural water of 3ppm Nitrate (10ppm is 11.3mg/l). So the levels Dr Joy is quoting can never be achievable in groundwater. That makes all his modelling nonsense.

Lake Taupo is another catchment with a nitrate problem. There they introduced restrictions on farming. However, most of the nitrogen going into the lake is from natural sources which they can't address. To quote the report:

: "Total nitrogen discharges into the lake amount to an estimated 1,360 tonnes of nitrogen (tN) per year, of which 804tN/year originate from natural or unmanageable sources, compared to 556tN/year from manageable or humaninduced sources. Pastoral activities account for 91 percent of all manageable sources of nitrogen loss. Specifically, non-dairy pasture land accounts for 79 percent of nitrogen discharges, while dairy pasture accounts for the remaining 12 percent."

Less irrigation was done on dairy farms but they show in one of the tables that nitrogen fixing scrub (gorse/ broom) is about a third of the of the nitrogen level of dairying in terms of kg/ ha/ year

Nitrogen Trading in Lake Taupo (motu.org.nz)

Not being an expert in any sense here I see the issue as follows

1. There is always some nitrate leaching in any natural system and it will vary depending upon all sorts of factors - so we don't need to be at zero.

2. Logically adding in larger quantities of nitrates through Urine, fertilizer, exotic legume plants (gorse, broom (and probably lupins) are significant as proven around Rotorua and Taupo lakes) will take the nitrate loads over natural levels. Its not all about farming as well - warning to Lupin lovers!!

3. Dairy farming produces a lot of income for NZ to have the standard of living we have.

4. At some level the nitrate level becomes dangerous to ecosystems - how much damage are we prepared to allow for the economic tradeoff? Quite a lot it seems but more pressure on this point coming in time.

5. At some level it becomes dangerous to Human health - it seems the level is lower than we thought. Voters seem a bit ambivilant but once it hits their family or a damaged baby, child or mother appears on TV/Social media etc I wouldn't want to be on the other side.

Point 5 is the real tipping point - once this is seen/observed/happens its all over for intensive farming as it becomes a very 1 dimensional Yes/No discussion.

I would encourage the intensive farming industry to start very hard at reducing this as its only a matter of time otherwise until point 5 occurs and economic benefit or not to the country it wont be nice for them.

As for Lupins - well good luck telling my elderly mother and her friends their lupins need to be removed!!!

A hard problem but one that needs to be addressed on many sides - not just farming alone.

i thought Legumes mainly fixed Nitrogen to nodules on their roots. I see the Taupo study puts it at 8 kg per Ha , vs 29 or so for dairy . And up to 70 in Canterbury .

Heres the study done in Rotorua lakes

http://www.rotorualakes.co.nz/vdb/document/110

Gorse doing around 35kg/ha/yr

Thanks , didn't think of the nitrogen from the decaying leaf matter. Very interesting , and wonder if it can be utilised to be spread onto farmlands / compost . would need to get it hot enough to kill the seeds , problem been they like heat .

Most N leaching is from animal urine.

Ryegrass pastures require lots of N from either fertiliser or legumes.

Animals require less protein than is present in ryegrass and so they urinate out the excess. Some is also excreted in faeces.

I doubt whether the N fixed by lupins is sufficient to cause major N leaching directly. It is when it gets concentrated in animal urine that the problem occurs.

KeithW

Yet the biggest source of nitrate leaching comes from market gardening - where there is nary a urine patch. Furthermore nitrate intake from water is small compared to eating a salad. Make Joy states 21.3 mg/l is "undrinkable" yet a spinach salad will give you a 300-400 mg dose. Is a spinach juice undrinkable? Given he is a vegan he should be more worried about his salads than nitrates in drinking water!

"On a per unit area basis, vegetable cropping systems produce by far the largest nitrate leaching to groundwater compared to any other land use type. Leaching losses range from 80 to 292 kg N/ha/yr depending on the amount of rainfall and the type of crop grown (Ledgard, 2001).

"Some experts contend that nitrate/nitrite ADIs are outdated anyway, and that higher levels are not only safe but actually beneficial – as long as they come from vegetables, not processed meats.

Having 300-400mg of nitrates in one go – potentially provided by a large rocket and spinach salad, or a beetroot juice shot – is the amount that’s been linked with falls in blood pressure, for example."

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190311-what-are-nitrates-in-food-s…

Yes, it is correct that the major source of nitrates in the human diet is from vegetables, not from drinking water.

The health science relating to nitrates is complex. It seems that a key question is whether the conditions in the digestive system are conducive to the nitrates being converted to nitrites. Accordingly the source of the nitrates may be important.

My personal judgement is that applying the cautionary principle we should be doing more to reduce nitrogen leaching. There are multiple ways that we can reduce N leaching associated with pastoral systems and that is where part of my own professional work is focused.

KeithW

The range for Pukekohe , which is market gardens , is 30 to 100 kg /Ha .

At least with market gardening, this could (and should ) be reduced by reducing N applied , and using ground covers/mulch / no till.

However, its not a matter of saying we don't have to do something in one area , because another area is worst progress needs to be made everywhere.

The weight of evidence strongly suggests that nitrates in drinking water do not cause bowel cancer, and it is not currently understood how dietary nitrates could cause bowel cancer

https://bowelcancernz.org.nz/new/position-statement-nitrates-drinking-w…

The material provided in this link is excellent.

The key message is that although nitrates in water is an important issue, it is very difficult to explain how it could be a cause of bowel cancer.

KeithW

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.