By Patrick Nolan*

Over the last few months there has been growing debate on the future of NZ Super, including on the pages of this website.

While this debate has been valuable what has been missing is recognition of some of the challenges involved in undertaking reform.

To borrow a line from the UK economist John Kay, “it is simply not the case that there are simple solutions to apparently difficult issues which policymakers have hitherto been too stupid or corrupt to implement.”

To illustrate, consider the example of the need to balance affordability and work incentives in the design of retirement income policies.

As NZ Super is a universal programme it has little effect on incentives to work for the people who receive it.

In contrast to working aged benefits the level of the payment does not abate if the recipient changes their wage rates or hours of work (although payments are affected by the personal tax scale).

The effect on work incentives is “little” not zero, as by changing the income of recipients it still has what economists call an “income effect.”

And there are of course effects associated with the taxes that are collected to fund the payments.

As the Retirement Commissioner recently noted, if future governments did want to reduce the future cost of NZ Super then one option would be to income test it at a certain age (say from 65 to 70).

Income testing is an option, as other ways of reducing cost, such as increasing the age of eligibility or making the benefit less generous, would lead to an increase in poverty in the over 65 age group, especially among Māori, Pacific people, women, and renters.

But, while income testing may lower cost without the same increase in poverty as these other options, it will also mean that as people change their incomes the level of the payment they receive would change also.

The result would be an increase in “effective marginal tax rates,” which are a measure of how taxes and the withdrawal of assistance can discourage work effort.

This highlights the challenges facing policymakers. There are no easy options that simultaneously improve affordability, reduce poverty, and strengthen financial incentives to work.

Any policy changes will require difficult choices and confronting trade-offs.

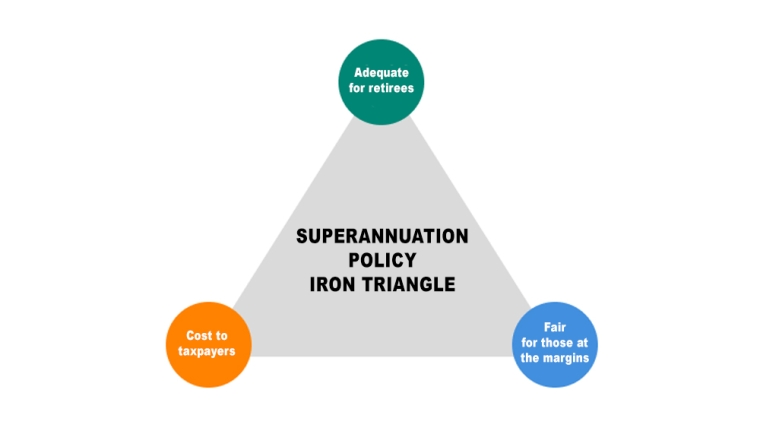

This won’t come as a surprise to long-term students of tax-transfer policy. In fact, trade-offs like these come up so often there is a name for them: “an iron-triangle.”

In an iron triangle it is impossible to move towards one corner (objective) without simultaneously moving further away from at least one of the other two corners (the other two objectives).

So where does this leave policymakers? The risk is that it can make change seem impossibly hard.

As former US President Harry Truman once said: “give me a one-handed Economist. All my economists say ‘on one hand’, then ‘but on the other’.”

Fortunately, there are ways of avoiding falling into this trap.

The first is to be clear on the objectives of reform. People are more likely to cooperate with a reform process if they know where it is heading.

And the purpose of reform to retirement income policy should not just be about saving money.

As I saw with fiscal consolidation in the UK a decade ago, looking at the problem in a narrow way will fail to lead to enduring reform.

This is like going on a “crash diet,” leading to a perception of underfunding without addressing the underlying drivers of cost.

But there are signs that the government is aware of this risk. We are, for example, told that social investment is not about simply reducing spending but is about improving how government works.

Or, as Nicola Willis has said, it is about doing better with our funding and delivery of services.

This needs a person-centred approach rather than looking at individual government policies or programmes in isolation.

It’s not just a question of the NZ Super settings, but KiwiSaver, private savings, and other transfers matter too.

It is also not just a question of doing what has been done before. Developing a longer-term plan requires new thinking as the needs of the community continue to change.

Look at pensioner poverty. For decades this was practically zero, as NZ Super was enough to lift incomes above the poverty threshold.

But this is not the case for all pensioners anymore – especially for those people who face high accommodation costs.

And change in the needs of the community is only going to continue. Population ageing will play an increasingly central role in shaping the policy agenda.

There are around 900,000 people over 65 in New Zealand. By 2050 this is expected to be almost 1.4 million. As a share of the total population, they will go from 17% to 23%.

So, we need hard thinking on a wide range of options, along with public engagement on the trade-offs inevitably involved in any reform.

Dr. Patrick Nolan is Director of Policy and Research at the Retirement Commission / Te Ara Ahunga Ora

5 Comments

Running the numbers quoted above I get an assumed population increase of 30k per year. If only that were true.

NZ Superannuation is not enough for those who need it, and too much for those who don't.

The net (after-tax) Super rate for an over-65 couple needs to be raised to the higher of 80% of the net average wage or 100% of the median wage, with other rates raised in proportion.

To temper the cost of that increase, a surtax needs to imposed on all other income received by people who enrol for NZ Super.

https://www.auckland.ac.nz/assets/business/about/our-research/research-…

The housing crisis is hitting senior renters especially hard, and their numbers are set to double in 25 years.

https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/07-12-2023/the-worrying-rise-of-retire…

https://renthub.nz/new-zealands-private-rental-market-leaving-pensioner…

https://enrichretirement.com/is-nz-ready-for-the-rise-in-older-renters/

https://www.ageingwellchallenge.co.nz/research/independence-and-housing…

https://www.1news.co.nz/2024/09/03/landlords-arent-ready-for-ageing-ten…

https://assets.retirement.govt.nz/public/Uploads/TAAORC-Population-Agei…

Blah, blah, blah, blah - what is it with interest.co and these interminable "opinions" on Super.

Here's a hard fact.

50% of NZ voters are aged 50+ and that's going up by 1% a year.

Super 2.0 is *never* going to happen for the simple reality of voter maths.

NZS currently costs ~5% of GDP and will peak at 8%

France, Spain and Italy currently spend >10% and nothing is blowing up.

One can cut 20% the current cost of Super by eliminating BS government bureaucracy in half an hour's graft.

Facts, no paper. As my children would say.

Oh, please.

As one of the interminable opinionators, could you try and address the issue in a constructive manner?

To suggest that because NZ spends relatively little on NZ Superannuation - much less than countries with older population structures such as France, Spain or Italy - then there cannot be a problem is utterly misleading. It is the efficiency with which we spend that matters. Suppose that you observed that New Zealanders spent a similar fraction of their income on food as people living in Italy, Spain or France. Surely you want also want to know whether our prices were the same to work out whether or not we were getting good value for our money? As it happens, food is significantly cheaper in Spain than New Zealand, so if you spend the same fraction of your money on food in New Zealand as Spain, you would get much less for your money. The same issue arises with NZ Superannuation. Do we have a retirement income system and an associated tax system that is efficient and gives good value for all the taxes that are collected to pay for it? Do we have a good way of taxing private retirement savings?. Could young and middle aged people be substantially better off for the same expenditure if the system were changed? Would the whole economy be better performing if NZ had a more efficient and less distortionary tax system? These questions are the questions that commentators are trying to grapple with, and they are raising them because basic economic principles suggest that NZ does not have a particularly efficient tax system and that there could be very large improvements in the returns from the same level of expenditure if the system were redesigned. Moreover, the cost of the current system is getting higher over time relative the benefits received, so younger people are disproportionately affected by these inefficiencies relative to older generations

But perhaps you are not interested in the efficiency of one of the two largest components of government expenditure, or the efficiency of a tax system that takes in nearly 30% of GDP? Unfortunately, if that is the case you have plenty of company. But it does explain why many others think that some reforms might be useful. Even if you could find an easy way to reduce the size of government by 20%, it is still worthwhile adopting a set of taxes and a retirement system that reduce the cost of raising this (smaller) amount of revenue, and which provides maximum benefit for the revenue that is raised.

AC

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.