By Martin Brook*

Given the death toll, it’s important we consider the impacts of Cyclone Gabrielle sensitively. But we must also begin looking into the history of land-use and planning decisions in areas worst hit by landslides.

One such area is the beach community at Muriwai in West Auckland, where two volunteer firefighters were tragically killed in a landslide.

Several homes were cut off by slips. Residents on the steep terrain of Domain Crescent were told to evacuate on foot, rather than drive, because the land was so unstable.

Here's hoping everyone impacted is able to evacuate on foot - what if there are residents with mobility issues ? Land movement detected at Muriwai street, residents asked to leave https://t.co/HTNlchGWyE

— Dr Lesley Gray (@DRR_NZ) February 17, 2023

Landslides can be a deadly hazard, but only when people are exposed to them. A landslide high in the Tararua mountain ranges is unlikely to pose a risk to anyone. But living near or within a landslide zone poses a clear risk.

This can be summarised as: risk = hazard x exposure x vulnerability.

Muriwai offers a case study of that equation. We already have a good understanding of the soils, landscape, geomorphology and exposure to landslide hazards – as well as the history of planning decisions that allowed houses to be built on land prone to slips.

An unstable history

Much of Muriwai, like other parts of Auckland’s west coast, is underlain by Kaihu Group sands. These are geologically young (Pleistocene age, less than 2.6 million years old) and form the high country around Muriwai.

The sands are weak and are poorly cemented, or completely uncemented, meaning there are “pore” spaces between the grains that are filled with air. During rainfall, water starts to fill these pore spaces.

Initially, this has a suction effect (negative pore pressure), whereby the water pulls the sand grains together, increasing strength. As water content increases, however, this negative pressure drops, and the sands fail and flow.

A good analogy is sand on a beach. If a little water is added, a steep-sided sand castle can be built. But if too much water is added, the castle collapses rapidly as a “flow-slide”.

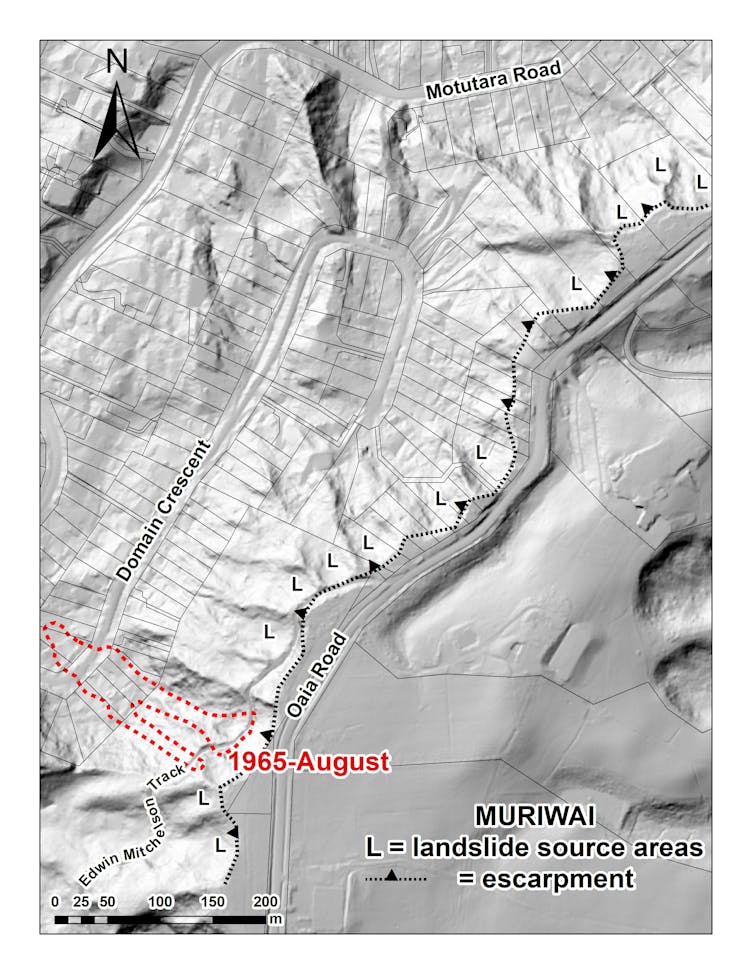

A prominent geomorphological feature of Muriwai is an escarpment of soft Pleistocene Kaihu Group dune sands that forms the crenulated ridgeline immediately west of Oaia Road. These crenulations, or “embayments”, represent the headscarps (or source areas) of landslides.

The figure below is a digital elevation model (DEM) based on 2016 data gathered by the remote-sensing method LiDAR. This uses airborne laser scanning of the land surface, which removes vegetation and exposes the land surface “geomorphology” underneath.

Landslides are denoted as “L”. Houses on Domain Crescent and Motutara Road are at the foot of the escarpment, below landslide source areas. They are constructed on Kaihu sands, with some of the houses built on debris from former landslides.

Landslides and the law

In August 1965, following heavy rainfall, fatal landslides over 200 metres long occurred on consecutive days at the south-east end of Domain Crescent, destroying houses and killing two people. The landslide extent is denoted in red hash in the figure above.

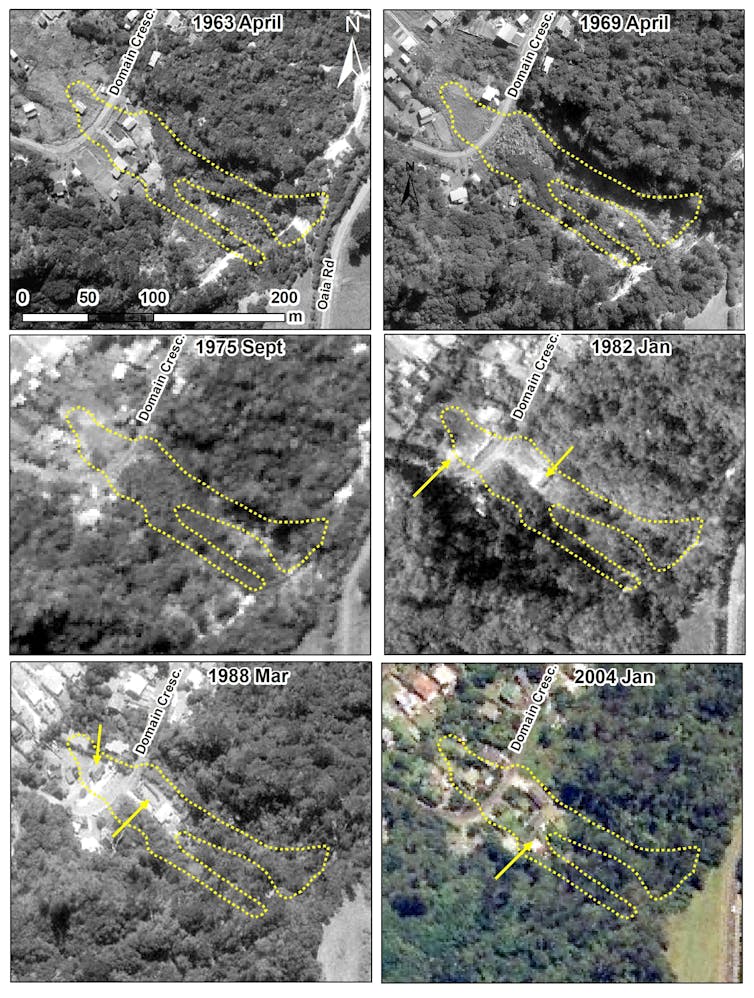

A 1966 New Zealand Geographer article recorded that witnesses said the landslide moved at 90 kilometres per hour. Soon after, it was reported a Rodney District Council engineer had stated no new houses would be built on the 1965 landslide footprint. This held until the early 1980s, when gradual house construction began again.

The timing of this new construction (denoted by the yellow arrows in the figure below) is intriguing. In 1981, the Local Government Amendment Act (section 641A) allowed councils to issue building permits for houses on unstable land prone to erosion, subsidence, slippage or inundation. Councils were also absolved of any civil liability.

Concern about the effects of section 641A was highlighted in 1986 by highly respected engineers Nick Rogers and Don Taylor in a paper published in New Zealand Engineering magazine, titled “Safe as houses”. While the Building Act 1991 and 2004 have improved matters, we are still dealing with section 641A’s legacy.

The Earthquake Commission (EQC) Act in 1993 was an important step forward for natural disaster insurance. But it stipulated that compensation can be refused if a house was constructed on unstable land.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Rodney District (which includes Muriwai) was ranked first nationally in having EQC claims rejected on the basis that houses had been built on existing unstable ground. The then EQC chief executive, David Middleton ONZM, appeared on the TV show Fair Go explaining this.

Real and moral hazards

No amount of geotechnical expertise or planning control can produce absolutely zero risk. But communities should be able to assume potential hazards are identified and they are not exposed to them.

Geomorphological mapping of landforms using high-resolution LiDAR DEMs can prove useful in planning and decision-making, as well as landslide susceptibility mapping. This is where a range of parameters – slope angle, soil type, thickness, rock type, vegetation cover and land use – are layered on top of the DEM, within a geographical information system.

The parameters are statistically modelled and a landslide susceptibility map is produced. In many parts of New Zealand, this map will probably not bring news some homeowners and land developers want to hear.

But such a map can be useful for hazard zoning. As the tragic events in Muriwai have shown over the years, the set-back of buildings below slopes is sometimes just as important as set-back from cliff edges at the top of slopes.

Other mitigation strategies include real-time monitoring of risk either in-situ or by satellite. Ultimately, costly slope engineering can be a solution.

However, as Rogers and Taylor wrote in 1986, property owners are often willing to accept risk until the hazard eventuates. In other cases, a “moral hazard” exists where there aren’t incentives to guard against risk because of protection from its consequences by insurance or EQC coverage.

Unfortunately, this risk can also tragically extend to third parties. Whether such risk-taking behaviour continues after the Auckland floods and Cyclone Gabrielle remains to be seen.

But understanding landscape geomorphology and using it as the basis for more resilient planning so we can truly build back better, or undertake managed retreat, is now imperative.![]()

*Martin Brook, Associate Professor of Applied Geology, University of Auckland. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

50 Comments

Great! So pleased to see this kind of detailed explanation and reporting. Totally relates to my earlier thought that;

Perhaps it is time to put a pause on mitigation, and simply avoid such hazards under Resource Management Act (RMA) section 5(2)c as a temporary emergency measure while we take stock in the aftermath of these events.

The three photos posted below that recommendation to: Impose nationwide minimum set-back rules for residential building which is on, above or below steep slopes are all of sections currently for sale on realestate.co.nz.

Central government needs to use its powers under the RMA to pause any further sales on, above or below steep slopes in order to get these LiDAR investigations done first.

The current Building Act 2004 section which allows buildings to be erected on known hazard sites is contained in sections 71-73; https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2004/0072/latest/DLM306819.html

And is a particular problem. People assume if a building consent has been granted - even if the property title has a section 73 notation on its title about the hazard - that the authorities thought the hazard risk low enough not to be a life-threatening concern. But in fact no individual risk assessment has been done at the time of granting the consent.

The reality is - these buildings simply should not be consented.

Wow, those pictured sites are insane... pin your home to the side of a cliff... what could go wrong?

Welcome to Welly :-).

What I've also found in looking at a lot of these new listing for vacant sections - is that the sections are sub-divisions and/or cross-leases of previously larger sections (in other words, they previously has acceptable 'buffer' or setbacks on the section). Absolutely nuts. Planning capture by the property owner/developer industry - under threat of court action should a regulator not grant the sub-division consent. No council wants to be sued (and fair enough) because in more cases than not the Environment Court rules on behalf of the developer.

That's why we have to "can" the option of 'proving' one can mitigate the hazard - and just go for a rule in all plans nationwide about minimum setbacks where "avoid" (i.e., prohibited/no development) is the only option where known erosion hazard exists.

Kate,

Of course you are right, but just how confident are you that even now, these lessons will be learned?

I fear that a few years down the track, memories will fade. We may then have to rely on insurance companies refusing to provide cover in areas known-like Muriwai- to be slip prone.

Not confident, which is why I'm hoping to put public pressure on central and local government to act decisively now.

Yes, it shouldn't even get near building consent - at planning/concept stage hazardous sites should be excluded from consideration. But its the litigiousness built into the RMA that allows developers and their QC's to push back against good hazard planning, motivated by the money involved in places like Oriental Bay, Papamoa etc. Maybe indirectly the inability to get insurance and therefore a mortgage will knock these sites out eventually.

You are right. But I don't think we can wait and rely on insurance denial to solve our problems. Many folks buy sections/homes and choose to self-insure (i.e., take on all the risk themselves) particularly if they don't need a mortgage. However, as we have seen in the past, when the time for bailout post-major disaster comes (e.g., Chch, Matata), they get included in any blanket compensation offered.

We need to prevent the occurrence/need for bailouts in future. And that means implementing more no-build zones/sections).

property owners are often willing to accept risk until the hazard eventuates

Or more pertinently, Developers are willing to accept risk as they expect to have sold the place before the hazard has struck.

I suppose there's also the 'economy' of cramming more homes onto a single street (rather than leaving poor sites undeveloped). That way the costs of infrastructures serving the street are spread among a greater number of properties... so suits both developers and councils.

Exactly. Time this cosy arrangement ended.

Good to see some sense being talked - we'll need a lot more of this.

And this time around, the vested-interest pressures have to be parried.

Yes. And to my mind the government now has the perfect opportunity to put in new land-use regulations, that might previously have been seen as draconian.

Hundreds of people die in cars every year, thousands of cars are written off each year, many worth a lot of money. Should they heavily regulate that too? Maybe no driving in the rain or at night for example.

The difference is, no one is expecting a handout from the taxpayer when they have a car crash.

Sure they do - and we do HEAVILY REGULATE.

WOFs, registrations, licensing driver's based on type of vehicle, speed limits on roads - just to name a few.

You need to stop making up silly examples - that do the demonstration of your intellect serious harm.

"In 1981, the Local Government Amendment Act (section 641A) allowed councils to issue building permits for houses on unstable land prone to erosion, subsidence, slippage or inundation."

Common sense was already absent, even in 1981.

National government - Muldoon years. Think Big.

The current Building Act 2004 (Labour government) also allows for granting building consents on land with known hazards, See sections 71-74.

It's 'the New Zealand way' regardless of the colour of government to date.

I wonder what ACT's position is now. A few months ago , they were campaigning for a loosening of restrictions , pretty much saying tho throw the RMA out , and build anywhere.

Yeah, they'll have gone a bit silent on that and keep pushing their line about removing zoning regulations to release more vacant land (ex-rural zone properties) as a means to bring section prices down.

Thing is - a lot of rural land contains drains (land-owner dug in order to combat flooding of paddocks). Developers come in, buy the land and fill in the drains. Disaster waiting to happen and it usually hits low-lying residential neighbourhoods in the adjacent area - many of which had been there for years (i.e., were subdivided and developed year and years earlier).

The Kāpiti Coast is a perfect example. Now found to be one of 44 council areas in NZ that is labelled a vulnerable community (vulnerable to flood risk and not wealthy enough to cover the cost of necessary flood prevention infrastructure).

Thing is - opening up more land means we won't need to cram more and more people into the marginal urban areas this article and yours identifies. But you oppose this solution also?

No, not at all against opening up suitable land for urban development. There's a great example of a new subdivision on suitable land in the Palmerston North area;

https://www.pncc.govt.nz/Participate-Palmy/Have-your-say/Aokautere-urban-growth

Ex- unproductive sheep and beef country. Elevated well above the Manawatu river - and appropriate section set-backs from tributary waterways. Land on the edge of these waterways to be vested in Council - hence room for flood protection works if required in future.

Here's an opposite example of land opened up to sub-division where consent for intensive urban development should not have been approved;

Ex rural residential/large lifestyle blocks bordering the Waikato River, where water ponded frequently (mounded groundwater) in its low-intensity state.

It all depends is the answer to your question.

...., where water ponded frequently (mounded groundwater) in its low-intensity state.

I am curious as to where you get this information from.... thanks

From memory it was a submission to the RC subdivision application given by a person who lived in the un-developed area.

Peacocke development does include a drainage plan, ponding water is very unlikely to be a problem.

https://hamilton.govt.nz/strategies-plans-and-projects/projects/peacock…

Why not though! Buyer beware and all that. Maybe the council should zone potential risk areas (so it shows up in a lim report for new buyers) but if a developer and engineer say they can overcome the risk then why stop someone developing on their own land.

Because 'develop' is a misnomer.

Because 'their own land' is a misnomer.

'Use to short-term advantage', is what the first one means.

The second? We hold tenure in trust for future generations. That's all.

And we're not doing a very good job of it....

Thanks - saved me the need to respond :-).

Tenure in trust for future generations. Perfect.

The digital elevation information is part of the council's available planning documents right?

My experience is that Councils spend waaay to much time and money focusing on amenity issues at the expense of risk issues when it comes to the issue of consents

and while we can change that for the future not sure what you do for existing but maybe a nationally developed risk rating could be recorded on all titles with those above a certain level directed to address the risk possibly with assistance. It has been done for earthquake buildings where public use is involved

I doubt any district-wide LiDAR studies have been done. All of NZ has been topographically mapped, but that's a different bit of data.

I could be proved wrong, but I think LiDAR is mainly used on a site or smaller area-specific basis.

its relaivelty new tech , first i saw it was in2021. Also requires aerial photos , don't think they can do it off Sat images.

https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/whareongaonga-landslide-21st-december-2…

Thanks - it's just great here that there are so many commentators with such a diverse knowledge-set.

I would suggest the opposite is true. District-wide LiDAR has been carried out throughout New Zealand and is freely available from the LINZ Data Service.

Greater Wellington Regional Council have done extensive LiDAR across Wairarapa plains ( not sure of elsewhere in the Region) to assist with flood modelling relating to the rivers there.

There's been some pretty widespread LIDAR mapping in NZ in the last few years:

Elevation data | Toitū Te Whenua - Land Information New Zealand (linz.govt.nz)

Great link - and great to see the number of areas already mapped and those underway.

Excellent, thanks for the link - will bookmark!

It could be a case of which regions weren't LiDAR mapped rather than were Kate. https://www.linz.govt.nz/products-services/data/types-linz-data/elevati…

You may be interested to see this, Kate. https://www.landwaterscience.co.nz/projects

Widespread use started in 2018 . Relatively recently.

Thanks for the links - will be interested to read about the projects. .

Hi Kate,

LiDAR is freely available for much of NZ via the LINZ data service. In some regions there are several years of LiDAR surveys available so changes in the land can be observed over time. The resolution of the data sets tends to vary over time. You need GIS software to view the data (e.g. QGIS which is freeware I believe) and it needs to be rendered as a "hillshade" to be of any visual use.

Seems to be a lot arguing for more regulation. What are we trying to protect?

- Loss of life? Surely you’d start at transport rather than housing.

- Loss of assets? Should the government try and protect us from that?

- Council liability? Surely more regulation would make them more likely to be liable.

Traditionally a way to win votes is to increase property values of existing housing, employing the method of placing more barriers against building new housing for "good reasons" can do this.

The next one 4/3/22 ??

https://metvuw.com/forecast/forecast1.php?type=rain®ion=swp&tim=240

With the extra heat going into the ocean, we can expect these to be perhaps yearly events. Certainly we have to plan to cover that.

And we've got the Alpine Fault coming....

Scout's motto, anyone?

According to media over the years, the Alpine Fault has been coming most of my life PDK - and and yet no one talked about Christchurch or Kaikoura. So yes prepare ourselves the best we can, but no point fretting about it.

Statistically, the Alpine Fault is coming in my lifetime. Not 100% by any shot, but something that has a 30% chance of happening in geological terms over a short time frame like 50 years is... well.. massive.

Conversely, the chance of an eruption in any given year in Auckland over an 80 year period (e.g. a lifetime) is (from memory) a shade under 1%.

Be prepared

That doesn’t look good, hopefully it doesn’t kick on

Absurd.

1) if the land was zoned for development EQC as a government agency should have paid out.

2) Complete failure on successive central governments to set national standards under the RMA with regards to natural hazards so we end up in the mess we are in now. Central government (taxpayers) should be the ones thus bailing out those affected by the cyclone.

Heck that is a shock that law change in 1981. 16 years after a fatal landslide on that landslide area. Also absolved of any blame. What kind of a country do we live in? Some great info from commentors so thanks.

Martin, thank you for an interesting article.

A few interesting points can be added to your observations about Muriwai.

In 1980, before building our house near the scarp of an old slip, but well back from the slip, we commissioned a geo-tech report.

The most interesting point in that report is that the engineer observed that from “an assessment of adjacent slopes the banks appear to have a natural repose of approximately 25 degrees.”

What he meant was that the sandy silty soil could be water-logged, yet not slump up to 25 degrees. The greater the slope above 25 degrees the greater the risk of slumping.This common-sense principle appears to have been abandoned years ago, especially when the toes of so many slopes have been removed for access ways and turning areas, thus increasing the natural gradients.

Muriwai was never developed/subdivided for its current uses.

It was largely intended for light-weight holiday homes, with minimum site-coverage, with only short-term periods of maximum occupancy during the summer months when dry soils had a greater chance of absorbing maximum wastewater discharge.

Modern Muriwai is a different beast. There are more permanent houses, there appears to be greater site coverage, with more impermeable surfaces, and a greater number of permanent residents during the wet winter months, (and, this year, the wet summer months.)

Modern Muriwai is a victim of its own success.

One can draw an obvious conclusion from your excellent DEM map: many sections, especially in Domain Crescent, are too small to contain a modern family home, with impermeable parking surfaces for multiple vehicles, and have enough area for wastewater dispersal and storm water retention.

Looking at the DEM map, and taking into account contour lines and overland flow paths it appears one house per three sections would be more appropriate.

Muriwai will not die, although it may become a smaller place.

In your concluding paragraphs you refer to a “landslide susceptibility map”. I think we need to add to this a record of where landslide susceptibility is exacerbated by human action, or, in this case, inaction.

One word I seldom see mentioned with regard to these slips: trees, especially pine trees.

Many areas of the scarp between Oaia Road and Motutara Road are littered with old pine trees - 40 to 80 years old? - all tilting away from the scarp. The same is true of the Council-owned Recreation Reserve along Oaia Road.

Has any analysis been done on the effect these pines have?

The trees are old, they are top-heavy. My understanding is that pine roots grow into the subsoil, thus causing water-piping along the roots, which eventually leads to slabs of the cliff breaking away.

A top-heavy pine, growing on a lean, will in a strong wind act as a lever on the cliff to which it is anchored.

Whilst Council may have been absolved from civil liability under section 641A, with regard to issuing building permits, I doubt they are immune to liability for the unpruned pines on the reserve, if those pines have been partially the cause of landslides.

The same may apply to the owners of the pines above Motutara Road.

Whilst certain types of foliage are known to bind and stabilise banks and cliffs, does the same apply to old-man top-heavy pines?

Did water-piping from tree roots contribute to the Muriwai slips?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.