By Christian Bogmans, Andrea Pescatori, and Ervin Prifti

Food prices, which reached a record earlier this year, have increased food insecurity and raised social tensions. They have also strained the budgets of governments struggling with rising food import bills and diminished capacity to fund extra social protection for the most vulnerable.

To better understand the scale of these unprecedented challenges for global policymakers, we quantify in new research the typical impact of four historically important drivers of food commodity prices. Our analysis, published in October’s special feature box in the latest World Economic Outlook, shows that:

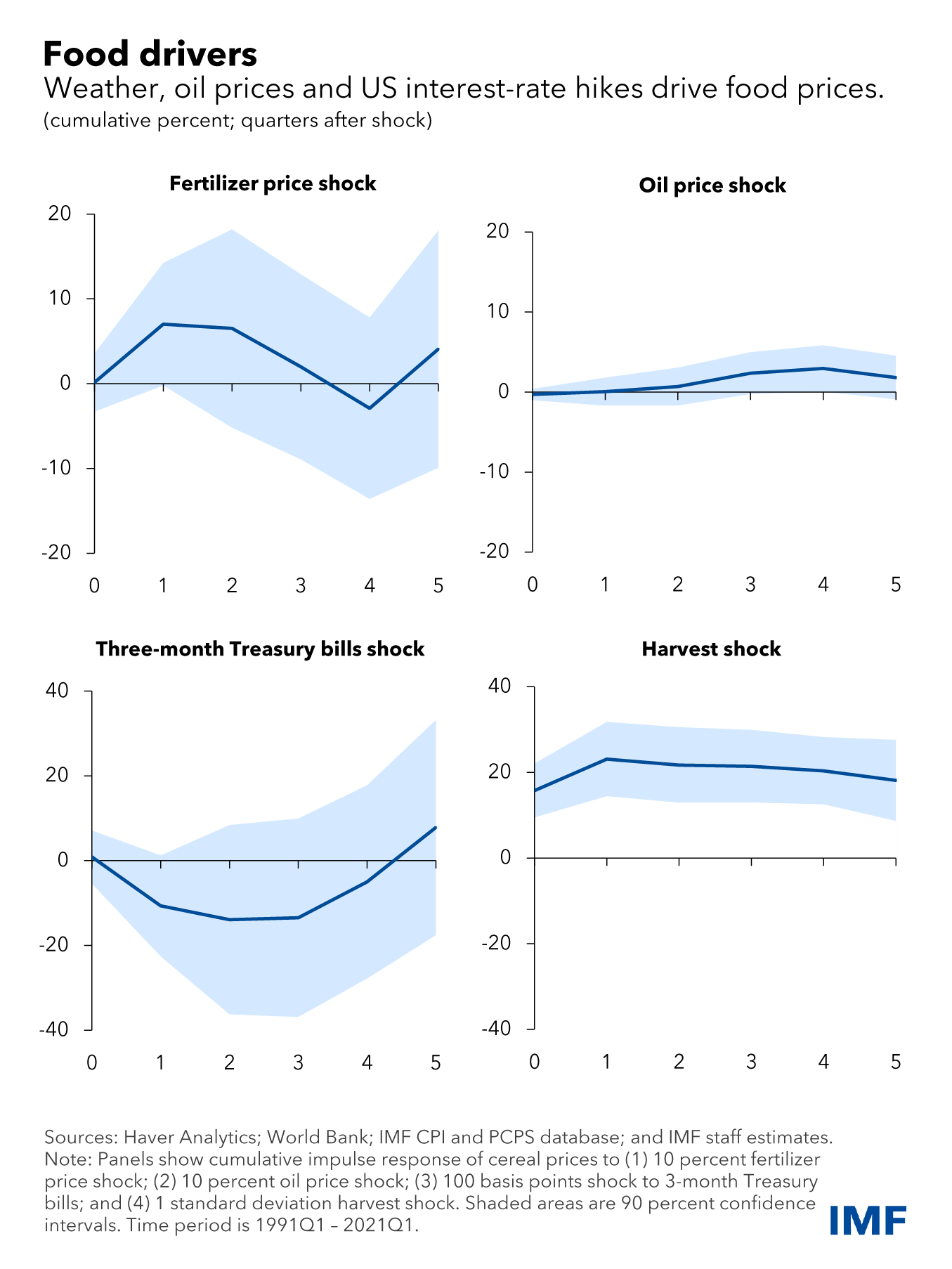

- A 1 percent drop in global harvests raises food commodity prices by 8.5 percent.

- A 1 percentage point increase in the Federal Reserve’s main interest rate reduces food commodity prices by 13 percent after one quarter.

- A 1 percent increase in fertiliser prices, which have climbed recently on the surge in natural gas prices, boosts food commodity prices by 0.45 percent.

- A 1 percent increase in oil prices increases food commodity prices by 0.2 percent.

These estimates can be used to better explain recent fluctuations in food prices and help define the outlook as different factors can exert opposing forces.

La Niña weather conditions are forecast to return for a third straight year, bringing below-average water temperatures to the east-central Pacific Ocean, according to the UN’s World Meteorological Organisation. Similar three-year periods occurred during the first world food crisis between 1973-76 and again between 1998-2001.

Moreover, the Black Sea Grain Initiative that provides safe export shipping from Ukraine could cause another shock to cereal supplies if it is suspended again by Russia. This alone would reduce global wheat and corn supplies by 1.5 percentage points, relative to current expectations, and in turn raise cereal prices by 10 percent within a year.

In addition, high energy prices raise fuel and fertiliser prices, boosting food production costs, but they also divert output from food to biofuels. Fertiliser prices are double what they were before the pandemic, even after a pullback in recent months.

Around 45 percent of any change in fertiliser prices usually feeds directly into global cereal prices within four quarters, IMF research shows. This suggests that part of the effect of high fertiliser prices may yet fully materialise. In poorer countries, where farmers use fertiliser more sparingly, reduced use may diminish harvests.

Downward price pressure

In addition to slowing global economic growth, which has a modest direct effect on food prices, central bank interest-rate hikes have significantly eased price pressures. The Federal Reserve, for example, is raising borrowing costs at the fastest pace in two decades. Higher rates tend to discourage inventory holdings and reduce speculative activities in commodity futures markets, thus putting downward pressure on food prices.

Our estimates suggest Fed tightening has already helped lower cereal prices since April and will continue to put downward pressure on prices through the end of next year.

Looking forward

It remains uncertain how the combination of harvest disruptions, energy prices, and monetary policy will play out. Trading in futures markets suggests that wholesale cereal prices will only drop 8 percent next year from the current highs. But our estimates indicate supply constraints could outweigh weakening demand, keeping prices elevated for the next few quarters.

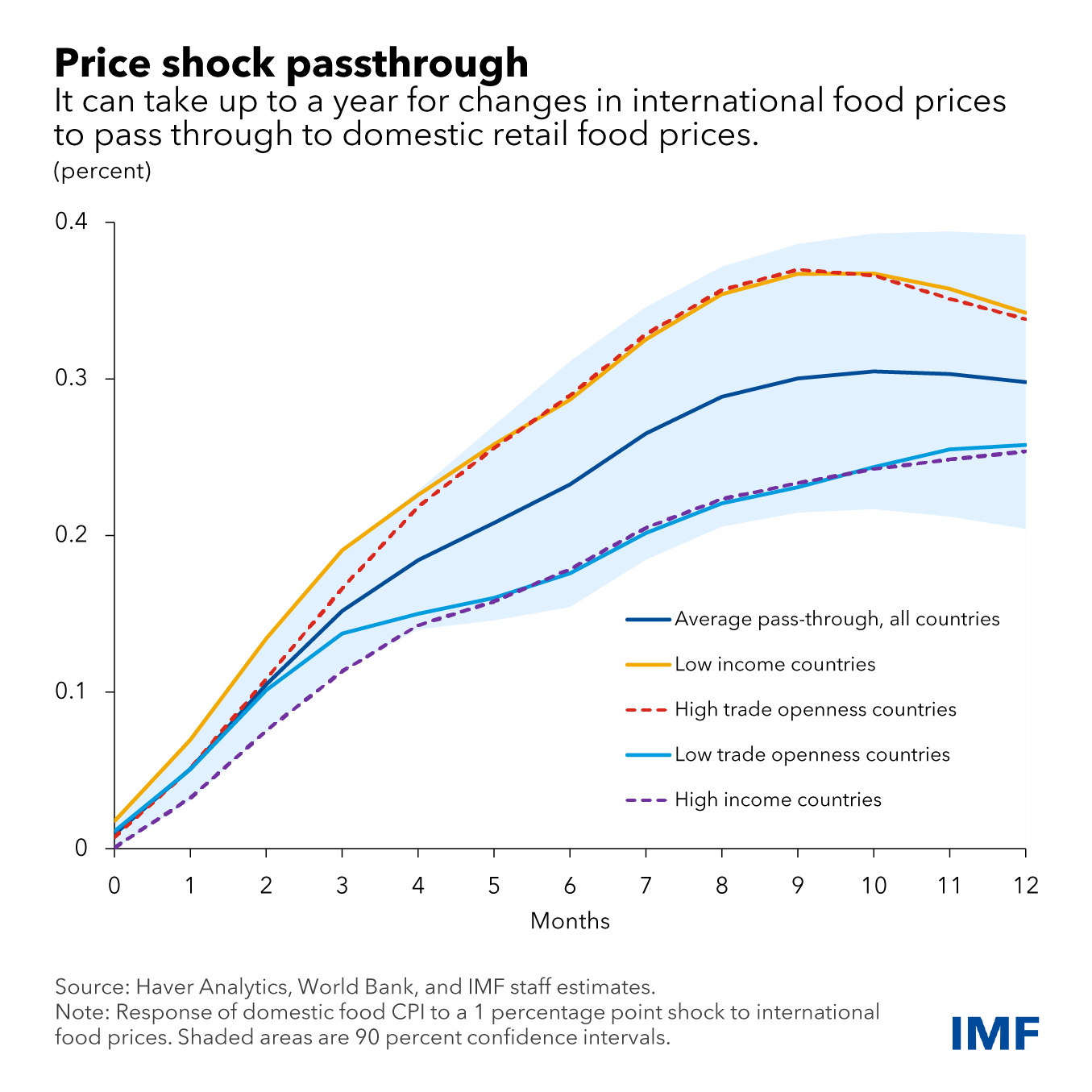

Higher international food prices are estimated to have added 6 percentage points to consumer food inflation in 2022. However, the passthrough to higher domestic retail food prices could take six to 12 months—another reason why, in addition to the recent weakening of emerging market currencies, many people will have to wait for relief from lower commodity prices.

Finally, the risk of food prices increasing again rather than declining during the next couple of quarters remains high. And if these risks weren’t enough, the impact of rising interest rates on food insecurity could be mixed. That’s because a resulting slowdown in economic activity may reduce personal incomes. Combined with still elevated food price levels, this could increase the number of food insecure people.

To defend against new price surges and allow food and fertilizer to flow to those who need it most, it remains vital that international trade remains free. In particular, the Black Sea grain corridor has facilitated cereal exports from Ukraine and brought down prices to pre-invasion levels, mitigating global hunger. It is important that there is also global access to fertilisers by eliminating trade barriers that are limiting global supply, as far as possible.

Countries should allow the increase in global prices to pass through to domestic prices while also increasing targeted social protection spending, as their budget allows. This is necessary to allow price signals to rebalance food markets and at the same time to protect vulnerable families' purchasing power. External debt relief and grants from international organizations could help finance the expansion of social assistance schemes in developing countries.

To help ease supply tensions, countries should stimulate domestic food production, while avoiding stockpiling and using reserves, especially those that have accumulated higher stock levels. Finally, high fuel prices at the pump have led policymakers to keep or increase the mandates for oil refineries to blend biofuels into their national fuel mix, with the intent of increasing supply. This extra demand on crops to produce feedstock for ethanol and other biofuels puts more pressure on food prices. Reducing biofuel mixing mandates would help lessen the impact of higher demand for biofuels on food prices.

Christian Bogmans, Andrea Pescatori, and Ervin Prifti are all economists at the IMF, but in different departments. This is a re-post of an article that ran on the IMF blog.

9 Comments

Chicken drumsticks $4.99 kg, lamb shoulder chops 12.99 kg and rump steak 14.99 kg at the supermarket this week. What else do you need?

Fruit and vegetables.

‘’ To help ease supply tensions, countries should stimulate domestic food production “

and this govt is determined to reduce food production

My take from this article is the food prices are determined by weather and war. Isolate out the weather if possible and the rest is war.

Fertiliser price is determined by the war via the gas price on a pre-pandemic and pre-war demand.

Of course one could throw in dumb political choices such as green energy into the mix as well.

Indeed. Green enregy is a really dumb choice! Lets stick to brown energy, AKA, burning until extinction. :-)

If we got rid of brown energy billions would die and the environmental impact would unprecedented. Hungry people don't care about the environment. A smart, managed transition to sustainable energy is still important, but we need to be smart about it and realise that we can't transition without them. In fact they are the catalyst that will make a transition possible.

Wait till the next strong El Niño... that on top of a warmer climate is going to be a doozy and lead to even more crop failures in key areas

As a farmer my assumption is this. Out of 10 years, one will be really good, one will be really bad and the rest will fall somewhere in the middle, but you almost never get a good year combined with good prices, the opposite is nearly always true.

As you can see, getting rid of oil and fertiliser is not really smart if you want people to eat. Please note that this is specifically related to vegan foods as the article doesn't really cover meat, dairy, poultry or fish.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.